Federal Income Tax Returns--Confidentiality Vs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Theft Literature Review

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Identity Theft Literature Review Author(s): Graeme R. Newman, Megan M. McNally Document No.: 210459 Date Received: July 2005 Award Number: 2005-TO-008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. IDENTITY THEFT LITERATURE REVIEW Prepared for presentation and discussion at the National Institute of Justice Focus Group Meeting to develop a research agenda to identify the most effective avenues of research that will impact on prevention, harm reduction and enforcement January 27-28, 2005 Graeme R. Newman School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany Megan M. McNally School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, Newark This project was supported by Contract #2005-TO-008 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

A Brief Description of Federal Taxes

A BRIEF DESCRIFTION OF FEDERAL TAXES ON CORPORATIONS SINCE i86i WMUAu A. SU. ND* The cost to the federal government of financing the Civil War created a need for increased revenue, and Congress in seeking new sources tapped theretofore un- touched corporate and individual profits. The Act of July x, x862, amending the Act of August 5, x86i, is the first law under which any federal income tax was collected and is considered to be largely the basis of our present system of income taxation. The tax acts of the Civil War period contained provisions imposing graduated taxes upon the gain, profits, or income of every person2 and providing that corporate profits, whether divided or not, should be taxed to the stockholders. Certain specified corporations, such as banks, insurance companies and transportation companies, were taxed at the rate of 5%, and their stockholders were not required to include in income their pro rata share of the profits. There were several tax acts during and following the War, but a description of the Act of 1864 will serve to show the general extent of the coiporate taxes of that period. The tax or "duty" was imposed upon all persons at the rate of 5% of the amount of gains, profits and income in excess of $6oo and not in excess of $5,000, 7Y2/ of the amount in excess of $5,ooo and not in excess of -$o,ooo, and io% of the amount in excess of $Sxooo.O This tax was continued through the year x87i, but in the last two years of its existence was reduced to 2/l% upon all income. -

Ways and Means Committee's Request for the Former President's

(Slip Opinion) Ways and Means Committee’s Request for the Former President’s Tax Returns and Related Tax Information Pursuant to 26 U.S.C. § 6103(f )(1) Section 6103(f )(1) of title 26, U.S. Code, vests the congressional tax committees with a broad right to receive tax information from the Department of the Treasury. It embod- ies a long-standing judgment of the political branches that the tax committees are uniquely suited to receive such information. The committees, however, cannot compel the Executive Branch to disclose such information without satisfying the constitutional requirement that the information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose. In assessing whether requested information could serve a legitimate legislative purpose, the Executive Branch must give due weight to Congress’s status as a co-equal branch of government. Like courts, therefore, Executive Branch officials must apply a pre- sumption that Legislative Branch officials act in good faith and in furtherance of legit- imate objectives. When one of the congressional tax committees requests tax information pursuant to section 6103(f )(1), and has invoked facially valid reasons for its request, the Executive Branch should conclude that the request lacks a legitimate legislative purpose only in exceptional circumstances. The Chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee has invoked sufficient reasons for requesting the former President’s tax information. Under section 6103(f )(1), Treasury must furnish the information to the Committee. July 30, 2021 MEMORANDUM OPINION FOR THE ACTING GENERAL COUNSEL DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY The Internal Revenue Code requires the Department of the Treasury (“Treasury”) and the Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) to keep tax returns and related information confidential, 26 U.S.C. -

Privacy and Publicity: the Two Facets of Personality Rights

Privacy and publicity Privacy and publicity: the two facets of personality rights hyperbole. In this context, personality In this age of endorsements and rights encompass the “right of privacy”, tabloid gossip, famous people which prohibits undue interference in need to protect their rights and a person’s private life. In addition to coverage in the media, reputations. With a growing number images of celebrities adorn anything from of reported personality rights cases, t-shirts, watches and bags to coffee mugs. India must move to develop its This is because once a person becomes legal framework governing the famous, the goods and services that he or commercial exploitation of celebrity she chooses to endorse are perceived to reflect his or her own personal values. By Bisman Kaur and Gunjan Chauhan, A loyal fan base is a captive market for Remfry & Sagar such goods, thereby allowing celebrities to cash in on their efforts in building up Introduction a popular persona. Intellectual property in India is no longer Unfortunately, a large fan base is a niche field of law. Stories detailing also seen by unscrupulous people as an trademark infringement and discussing opportunity to bring out products or the grant of geographical indications services that imply endorsement by an routinely make their way into the daily individual, when in fact there is no such news headlines. From conventional association. In such cases the individual’s categories of protection such as patents, “right of publicity” is called into play. trademarks, designs and copyright, IP laws The right of publicity extends to every have been developed, often by judicial individual, not just those who are famous, innovation, to encompass new roles and but as a practical matter its application areas of protection. -

RESTORING the LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E

COPYRIGHT © 2017 VIRGINIA LAW REVIEW ASSOCIATION RESTORING THE LOST ANTI-INJUNCTION ACT Kristin E. Hickman* & Gerald Kerska† Should Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents be eligible for pre-enforcement judicial review? The D.C. Circuit’s 2015 decision in Florida Bankers Ass’n v. U.S. Department of the Treasury puts its interpretation of the Anti-Injunction Act at odds with both general administrative law norms in favor of pre-enforcement review of final agency action and also the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the nearly identical Tax Injunction Act. A 2017 federal district court decision in Chamber of Commerce v. IRS, appealable to the Fifth Circuit, interprets the Anti-Injunction Act differently and could lead to a circuit split regarding pre-enforcement judicial review of Treasury regulations and IRS guidance documents. Other cases interpreting the Anti-Injunction Act more generally are fragmented and inconsistent. In an effort to gain greater understanding of the Anti-Injunction Act and its role in tax administration, this Article looks back to the Anti- Injunction Act’s origin in 1867 as part of Civil War–era revenue legislation and the evolution of both tax administrative practices and Anti-Injunction Act jurisprudence since that time. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................... 1684 I. A JURISPRUDENTIAL MESS, AND WHY IT MATTERS ...................... 1688 A. Exploring the Doctrinal Tensions.......................................... 1690 1. Confused Anti-Injunction Act Jurisprudence .................. 1691 2. The Administrative Procedure Act’s Presumption of Reviewability ................................................................... 1704 3. The Tax Injunction Act .................................................... 1707 B. Why the Conflict Matters ....................................................... 1712 * Distinguished McKnight University Professor and Harlan Albert Rogers Professor in Law, University of Minnesota Law School. -

Freedom of Information: a Comparative Legal Survey

JeXo C[dZ[b ^h i]Z AVl J^[_cfehjWdY[e\j^[h_]^jje Egd\gVbbZ9^gZXidgl^i]6GI>8A:&.!<adWVa 8VbeV^\c [dg ;gZZ :megZhh^dc! V aZVY^c\ _d\ehcWj_edehj^[h_]^jjeadem_iWd ^ciZgcVi^dcVa ]jbVc g^\]ih C<D WVhZY ^c _dYh[Wi_d]boYedijWdjh[\hW_d_dj^[ AdcYdc! V edh^i^dc ]Z ]Vh ]ZaY [dg hdbZ iZc nZVgh# >c i]Vi XVeVX^in! ]Z ]Vh ldg`ZY cekj^ie\Z[l[befc[djfhWYj_j_ed[hi" ZmiZch^kZan dc [gZZYdb d[ ZmegZhh^dc VcY g^\]i id ^c[dgbVi^dc ^hhjZh ^c 6h^V! 6[g^XV! Y_l_bieY_[jo"WYWZ[c_Yi"j^[c[Z_WWdZ :jgdeZ! i]Z B^YYaZ :Vhi VcY AVi^c 6bZg^XV! ]el[hdc[dji$M^Wj_ij^_ih_]^j"_i_j gjcc^c\ igV^c^c\ hZb^cVgh! Xg^i^fj^c\ aVlh! iV`^c\XVhZhidWdi]cVi^dcVaVcY^ciZgcVi^dcVa h[WbboWh_]^jWdZ^em^Wl[]el[hdc[dji WdY^Zh! VYk^h^c\ C<Dh VcY \dkZgcbZcih! VcY ZkZc ldg`^c\ l^i] d[ÒX^Vah id egZeVgZ iek]^jje]_l[[\\[Yjje_j5J^[i[Wh[ YgV[ig^\]iid^c[dgbVi^dcaVlh#>cVYY^i^dcid iec[e\j^[gk[ij_edij^_iXeeai[[ai ]^h ldg` l^i] 6GI>8A:&.! ]Z ]Vh egdk^YZY ZmeZgi^hZ dc i]ZhZ ^hhjZh id V l^YZ gVc\Z jeWZZh[ii"fhel_Z_d]WdWYY[ii_Xb[ d[ VXidgh ^cXajY^c\ i]Z LdgaY 7Vc`! kVg^djh JCVcYdi]Zg^ciZg\dkZgcbZciVaWdY^Zh!VcY WYYekdje\j^[bWmWdZfhWYj_Y[h[]WhZ_d] cjbZgdjh C<Dh# Eg^dg id _d^c^c\ 6GI>8A: \h[[Zece\_d\ehcWj_ed"WdZWdWdWboi_i &.!IdWnBZcYZaldg`ZY^c]jbVcg^\]ihVcY ^ciZgcVi^dcVa YZkZadebZci! ^cXajY^c\ Vh V e\m^Wj_imeha_d]WdZm^o$ hZc^dg ]jbVc g^\]ih XdchjaiVci l^i] Dm[Vb 8VcVYVVcYVhV]jbVcg^\]iheda^XnVcVanhi 68dbeVgVi^kZAZ\VaHjgkZn Vi i]Z 8VcVY^Vc >ciZgcVi^dcVa 9ZkZadebZci ;gZZYdbd[>c[dgbVi^dc/ 6\ZcXn8>96# ÆJ^[\h[[Ôeme\_d\ehcWj_edWdZ_Z[Wi IdWn BZcYZa ]Vh ejWa^h]ZY l^YZan! b_[iWjj^[^[Whje\j^[l[hodej_ede\ 6 8dbeVgVi^kZ AZ\Va HjgkZn Xdcig^Wji^c\ id cjbZgdjh 6GI>8A: &. -

Federal Register

> 11TTTO& ' FEDERAL REGISTER VOLUME 3 \ 1934 NUMBER 141 i/AHTED^ W a sh in gton , T h u rsd a y, J u ly 21, 1938 Rules, Regulations, Orders his hand and caused the seal of the De CONTENTS partment of Agriculture to be affixed in the city of Washington, District of Co RULES, REGULATIONS, ORDERS TITLE 7—AGRICULTURE lumbia, this 19th day of July, 1938. T itle 7—A griculture: [ seal! M. L. W ilson, Agricultural Adjustment Ad AGRICULTURAL ADJUSTMENT Acting Secretary of Agriculture. ADMINISTRATION ministration: Page [F. R. Doc. 38-2079; Filed, July 20,1938; Fresh prunes grown in Uma P roclamation W ith Respect to B ase 9:32 a. m.] tilla County, Oreg., Walla P eriod to be U sed for P urpose of Walla and Columbia M arketing A greement and O rder Counties, Wash.: R egulating H andling of F resh P runes Base period for marketing G rown in U matilla County in State Order R egulating the H andling in In agreement and order__1779 of Oregon, and W alla W alla and terstate and Foreign Commerce, and Order regulating handling Columbia Counties in State of W ash Such H andling as D irectly Burdens, in interstate, etc., com ington Obstructs or Affects I nterstate or F oreign Commerce of Fresh P runes merce_________________ 1779 By virtue of the authority vested in G rown in U matilla County in State Mainland cane sugar area the Secretary of Agriculture by the terms of Oregon and W alla W alla and Co ferais, determination of and provisions of Public Act No. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Preface ..................................................................................................... ix Introductory Notes to Tables ................................................................. xi Chapter A: Selected Economic Statistics ............................................... 1 A1. Resident Population of the United States ............................................................................3 A2. Resident Population by State ..............................................................................................4 A3. Number of Households in the United States .......................................................................6 A4. Total Population by Age Group............................................................................................7 A5. Total Population by Age Group, Percentages .......................................................................8 A6. Civilian Labor Force by Employment Status .......................................................................9 A7. Gross Domestic Product, Net National Product, and National Income ...................................................................................................10 A8. Gross Domestic Product by Component ..........................................................................11 A9. State Gross Domestic Product...........................................................................................12 A10. Selected Economic Measures, Rates of Change...............................................................14 -

![Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] ______](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8699/land-title-records-in-the-new-york-state-archives-new-york-state-archives-information-leaflet-11-draft-1178699.webp)

Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] ______

Land Title Records in the New York State Archives New York State Archives Information Leaflet #11 [DRAFT] __________________________________________________________________________________________________ Introduction NEW YORK STATE ARCHIVES Cultural Education Center Room 11A42 The New York State Archives holds numerous records Albany, NY 12230 documenting title to real property in New York. The records range in date from the early seventeenth century to Phone 518-474-8955 the near present. Practically all of the records dating after FAX 518-408-1940 the early nineteenth century concern real property E-mail [email protected] acquired or disposed by the state. However, many of the Website www.archives.nysed.gov earlier records document conveyances of real property ______________________________________________ between private persons. The Archives holds records of grants by the colony and state for lands above and under Contents: water; deeds issued by various state officers; some private deeds and mortgages; deeds to the state for public A. Indian Deeds and Treaties [p. 2] buildings and facilities; deeds and cessions to the United B. Dutch Land Grants and Deeds [p. 2] States; land appropriations for canals and other public purposes; and permits, easements, etc., to and from the C. New York Patents for Uplands state. The Archives also holds numerous records relating and Lands Under Water [p. 3] to the survey and sale of lands of the colony and state. D. Applications for Patents for Uplands and Lands Under Water [p. 6] This publication contains brief descriptions of land title records and related records in the Archives. Each record E. Deeds by Commissioners of Forfeitures [p. 9] series is identified by series number (five-character F. -

The Revenue Act of 1924: Publicity, Tax Cuts, Response

The Revenue Act of 1924: Publicity, Tax Cuts, Response Daniel Marcin∗ March 25, 2014 Abstract The elasticity of taxable income (ETI) with respect to the marginal net-of-tax rate is an estimate of the aggregate response to tax rate changes. It is estimated without attributing cause to avoidance, evasion, or changes in economic growth. Historical ETI estimates in the public nance literature often rely on assumptions about income dynamics. A provision in the Revenue Act of 1924 for publicity of income tax returns allowed major newspapers to run lists of names, addresses, and tax payments in their pages. From these records, I constructed a dataset of very high income taxpayers. Over 10,000 individuals can be easily matched between the two years. In addition, the Revenue Act of 1924 sharply cut marginal tax rates. These changes can be used to estimate the ETI without distribution or rank preservation assumptions. Preliminary estimates indicate a positive ETI around 0.3 to 0.6, consistent with previous research. ∗Acknowledgements: Paul Rhode, David Albouy, Martha Bailey, and Josh Hausman for serving on my committee, seminar participants at Michigan, the Midwest Economics Association, the Economics and Busi- ness History Society, the World Cliometric Congress, and Nic Duquette for various helpful comments. Fund- ing: SRA, OTPR, Rackham, EHA, MITRE 1 I wish it to be understood that I have not the slightest prejudice against multi-millionaires. I like them. But I always feel this way when I meet one of them: You have made millionsgood; that means you have something in you. I wish you would show it. -

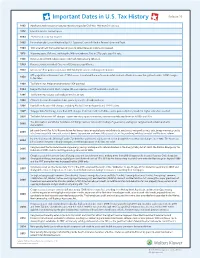

Important Dates in U.S. Tax History Release 16

Release 16 Important Dates in U.S. Tax History 1862 Abraham Lincoln enacts emergency measure to pay for Civil War: Minimum 3% tax rate. 1872 Lincoln’s income tax law lapses. 1894 2% federal income tax enacted. 1895 Income tax ruled unconstitutional by U.S. Supreme Court in Pollack v. Farmer’s Loan and Trust. 1909 16th amendment that authorizes Congress to collect taxes on income is proposed. 1913 Wyoming casts 37th vote, ratifying the 16th amendment. One in 271 people pays 1% rate. 1926 Revenue Act of 1926 reduces taxes: Too much money being collected. 1939 Revenue statutes codified. One out of 32 citizens pays 4% rate. 1943 One out of three people pays taxes. Withholding on salaries and wages introduced. 875-page Internal Revenue Code of 1954 passes. Considered the most monumental overhaul of federal income tax system to date. 3,000 changes 1954 to tax rules. 1969 Tax Reform Act: Major amendments to 1954 overhaul. 1984 Reagan Tax Reform Act: Most complex bill ever, requires over 180 technical corrections. 1986 Tax Reform Act reduces tax brackets from five or two. 1993 Clinton’s Revenue Reconciliation Act passes by one Vice Presidential vote. 1996 Four bills make over 700 changes, including Medical Savings Accounts and SIMPLE plans. 1997 Taxpayer Relief Act brings more than 800 changes. Child tax credit, Roth IRAs, capital gains reduction, breaks for higher education enacted. 2001 Tax Relief Act creates 441 changes. Lowers tax rates, repeals estate tax, increases contribution limits on 401(k)s and IRAs. The Job Creation and Worker Assistance Act brings business tax relief, including a 5-year net operating loss carryback and extends and adds 2002 depreciation. -

Right of Privacy and Rights of the Personality

AGTA Instituti Upsaliensis Iurisprudentiae Gomparativae VIII RIGHT OF PRIVACY AND RIGHTS OF THE PERSONALITY A COMPARATIVE SURVEY Working paper prepared for the Nordic Conferen.ee on privacy organized by the International Commission of Jurists, Stockholm M ay 1967 BY STIG STRÜMHOLM STOCKHOLM P. A. NORSTEDT & SÜNERS FÜRLAG ACTA Institut! Upsaliensis Iurisprudentiae Oomparativae AGTA Instituti Upsaliensis Iurisprudentiae Comjmrativae Edidit ÂKE MALMSTROM VIII RIGHT OF PRIVACY AND RIGHTS OF THE PERSONALITY A COMPARATIVE SURVEY (Working Paper prepared for the Nordic Conférence on Privacy organized by the International Commission of Jurists, Stockholm May 1967) By STIG STRÜMHOLM S T O C K H O L M P. A. N O RSTEDT & S ONE R S FÜRLAG © P. A. Norstedt & Sôners fôrlag 1967 Boktryckeri AB Thule, Stockholm 1967 PREFACE One of the author’s most eminent teachers in private law in the Uppsala Faculty of Law once claimed that an action in tort ought to lie against those légal writers who take up a subject to treat it broadly enough to deter others from writing about it but not deeply enough to give any final answers to the questions discussed. Were the law so severe, the present author would undoubtedly have to face a lawsuit for venturing to publish this short study on a topic which demands lengthy and careful considération on almost every point and which has already given rise to an extensive body of case law and of légal writing. This préfacé can be considered as the au thor’s plaidoyer in that action, fortunately imaginary. The present study was prepared at the request, and with the most active personal and material support, of the International Commis sion of Jurists as a working paper for the Nordic Conférence of Jurists, organized by the Commission in Stockholm in May, 1967.