I Can Live No Longer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Under Law William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Popular Media Faculty and Deans 1977 Justice Under Law William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Justice Under Law" (1977). Popular Media. 264. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media/264 Copyright c 1977 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/popular_media INL Chief Justice John Marshall, portrayed by Edward Holmes, is the star of the P.B.S. "Equal Justice under Law" series. By William F. Swindler T HEBuilding-"Equal MOTTO on the Justice facade under of-the Law"-is Supreme also Court the title of a series of five films that will have their pre- mieres next month on the Public Broadcasting Service network. Commissioned by the Bicentennial Committee of the Judicial Conference of the United States and produced for public television by the P.B.S. national production center at WQED, Pittsburgh, the films are intended to inform the general public, as well as educational and professional audiences, on the American constitutional heritage as exemplified in the major decisions of the Supreme Court under Chief Justice John Marshall. ABOVE: Marshall confers with Justice Joseph Story (left) and Jus- Four constitutional cases are dramatized in the tice Bushrod Washington (right). BELOW: Aaron Burr is escorted to series-including the renowned judicial review issue jail. in Marbury v. Madison in 1803, the definition of "nec- essary and proper" powers of national government in the "bank case" (McCulloch v. -

December 2009 Page 1 President's Remarks Once Again It Is Year-End

President’s Remarks Once again it is year-end, and once again we are conducting our annual request for member donations to help support MCMA. Last year, we were pleased that the number of member responses increased over 50% from the year previous, and this year we are hoping to see a similar increase in participation. The turbulence of the markets over these past two years, combined with the absence of “safe” investment alternatives that can generate the returns needed to meet our obligations, have really driven home the need to supplement the income we derive from our investments. Your support can and will help, so once again I will say it: if you are able to and wish to make a year-end donation to benefit MCMA, your gift will be greatly appreciated, it is tax-deductible (you will receive a written acknowledgement), and you may instruct Rick Purdy to record it as an anonymous contribution if you so choose. Thank you again. Marty Joyce Recent Happenings Our October Quarterly was held at Spinelli’s in Lynnfield, and we were pleased to have as our guest speaker Mr. Ed McCabe, Maritime Program Director for the Hull Lifesaving Museum. MCMA has supported the Museum’s boat building program on the Boston waterfront for several years, and Mr. McCabe was able to give us an interesting overview of the Museum’s history, details of the program itself, and most importantly the results they are achieving with troubled youths who really want to succeed. A moment of silence was observed in memory of recently deceased Past President Raymond Purdy and member Byron R. -

Spring/Summer 2018

TIMELINE SPRING/SUMMER 2018 Stories of Loss A Landscape of Landmarks Fashion Agency and Survival As we continue to engage in meaningful Kristen Stewart, Nathalie L. Klaus Curator conversations, David Voelkel, Elise H. Wright of Costume and Textiles, explores Pretty Meg Hughes, Curator of Archives, highlights Curator of General Collections, discusses Powerful: Fashion and Virginia Women, some of what visitors will see in the timely the relevance of the upcoming exhibition her new show examining fashion as an exhibition . Pandemic: Richmond Monumental: Richmond Monuments (1607–2018). instigator of social change. 1 5 6 A B C D A A The Valentine’s new exhibition Pandemic: Richmond traces the B to serve as a turning place for city’s encounters with seven contagious diseases: smallpox, boats and barges and as a source tuberculosis, cholera, typhoid fever, polio, the 1918–1919 of water for mills, its standing influenza and HIV/AIDS. These diseases shaped Richmond’s water and sewage contaminants history, changing where and how people lived and prompting life- made it a perfect environment saving advances in health care. for cholera. Here is a closer look at Richmond’s experience with cholera, just Richmonders waited in fear as one of the diseases featured in this timely exhibition: cholera broke out in U.S. cities, finally reaching Tidewater by Cholera first appeared in pandemic form in the early-19th century, August 1832. In September, the with at least seven major global outbreaks between 1817 and the city saw its first case, caught present. This terrifying new disease produced severe vomiting by an 11-year-old enslaved and diarrhea that could lead to coma and death within hours. -

The Amenability of the President to Suit Laura Krugman Ray Widener University

Kentucky Law Journal Volume 80 | Issue 3 Article 6 1992 From Prerogative to Accountability: The Amenability of the President to Suit Laura Krugman Ray Widener University Follow this and additional works at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj Part of the President/Executive Department Commons Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits you. Recommended Citation Ray, Laura Krugman (1992) "From Prerogative to Accountability: The Amenability of the President to Suit," Kentucky Law Journal: Vol. 80 : Iss. 3 , Article 6. Available at: https://uknowledge.uky.edu/klj/vol80/iss3/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in Kentucky Law Journal by an authorized editor of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From Prerogative to AcCountability: The Amenability of the President to Suit By LAURA KRUGMAN RAY* INTRODUCTION When in the fall of 1990 President George Bush announced a shift in his Persian Gulf strategy from a defensive to an offensive posture, a number of lawsuits were filed against the President questioning his power to commence military operations against Iraq without congressional approval.' In the controversy surround- ing the President's policy, little attention was paid to the form of this protest, and yet the filing of these lawsuits represents a quiet revolution in presidential accountability under the rule of law. From the end of the Civil War until the final days of the Watergate drama, legal gospel held that the President of the United States enjoyed immunity from suit. -

From the American Revolution Through the American Civil War"

History 216-01: "From the American Revolution through the American Civil War" J.P. Whittenburg Fall 2009 Email: [email protected] Office: Young House (205 Griffin Avenue) Web Page: http://faculty.wm.edu/jpwhit Telephone: 757-221-7654 Office Hours: By Appointment Clearly, this isn't your typical class. For one thing, we meet all day on Fridays. For another, we will spend most of our class time "on-site" at museums, battlefields, or historic buildings. This class will concentrate on the period from the end of the American Revolution through the end of the American Civil War, but it is not at all a narrative that follows a neat timeline. I’ll make no attempt to touch on every important theme and we’ll depart from the chronological approach whenever targets of opportunities present themselves. I'll begin most classes with some sort of short background session—a clip from a movie, oral reports, or maybe something from the Internet. As soon as possible, though, we'll be into a van and on the road. Now, travel time can be tricky and I do hate to rush students when we are on-site. I'll shoot for getting people back in time for a reasonably early dinner—say 5:00. BUT there will be times when we'll get back later than that. There will also be one OPTIONAL overnight trip—to the Harper’s Ferry and the Civil War battlefields at Antietam and Gettysburg. If these admitted eccentricities are deeply troubling, I'd recommend dropping the course. No harm, no foul—and no hard feelings. -

Slavery in Ante-Bellum Southern Industries

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of BLACK STUDIES RESEARCH SOURCES Microfilms from Major Archival and Manuscript Collections General Editors: John H. Bracey, Jr. and August Meier SLAVERY IN ANTE-BELLUM SOUTHERN INDUSTRIES Series C: Selections from the Virginia Historical Society Part 1: Mining and Smelting Industries Editorial Adviser Charles B. Dew Associate Editor and Guide compiled by Martin Schipper A microfilm project of UNIVERSITY PUBLICATIONS OF AMERICA An Imprint of CIS 4520 East-West Highway • Bethesda, MD 20814-3389 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Slavery in ante-bellum southern industries [microform]. (Black studies research sources.) Accompanied by printed reel guides, compiled by Martin P. Schipper. Contents: ser. A. Selections from the Duke University Library / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Randolph Boehm—ser. B. Selections from the Southern Historical Collection, University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill—ser. C. Selections from the Virginia Historical Society / editorial adviser, Charles B. Dew, associate editor, Martin P. Schipper. 1. Slave labor—Southern States—History—Sources. 2. Southern States—Industries—Histories—Sources. I. Dew, Charles B. II. Boehm, Randolph. III. Duke University. Library. IV. University Publications of America (Firm). V. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Library. Southern Historical Collection. VI. Virginia Historical Society. HD4865 306.3′62′0975 91-33943 ISBN 1-55655-547-4 (ser. C : microfilm) CIP Compilation © 1996 by University Publications -

Early History of Thoroughbred Horses in Virginia (1730-1865)

Early History of Thoroughbred Horses in Virginia (1730-1865) Old Capitol at Williamsburg with Guests shown on Horseback and in a Horse-drawn Carriage Virginia History Series #11-08 © 2008 First Horse Races in North America/Virginia (1665/1674) The first race-course in North America was built on the Salisbury Plains (now known as the Hempstead Plains) of Long Island, New York in 1665. The present site of Belmont Park is on the Western edge of the Hempstead Plains. In 1665, the first horse racing meet in North America was held at this race-course called “Newmarket” after the famous track in England. These early races were match events between two or three horses and were run in heats at a distance of 3 or 4 miles; a horse had to complete in at least two heats to be judged the winner. By the mid-18th century, single, "dash" races of a mile or so were the norm. Virginia's partnership with horses began back in 1610 with the arrival of the first horses to the Virginia colonies. Forward thinking Virginia colonists began to improve upon the speed of these short stocky horses by introducing some of the best early imports from England into their local bloodlines. Horse racing has always been popular in Virginia, especially during Colonial times when one-on-one matches took place down village streets, country lanes and across level pastures. Some historians claim that the first American Horse races were held near Richmond in Enrico County (now Henrico County), Virginia, in 1674. A Match Race at Tucker’s Quarter Paths – painting by Sam Savitt Early Racing in America Boston vs Fashion (The Great Match Race) Importation of Thoroughbreds into America The first Thoroughbred horse imported into the American Colonies was Bulle Rock (GB), who was imported in 1730 by Samuel Gist of Hanover County, Virginia. -

Virginia ' Shistoricrichmondregi On

VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUPplanner TOUR 1_cover_17gtm.indd 1 10/3/16 9:59 AM Virginia’s Beer Authority and more... CapitalAleHouse.com RichMag_TourGuide_2016.indd 1 10/20/16 9:05 AM VIRGINIA'S HISTORIC RICHMOND REGION GROUP TOURplanner p The Virginia Museum of Fine Arts’ permanent collection consists of more than 35,000 works of art. © Richmond Region 2017 Group Tour Planner. This pub- How to use this planner: lication may not be reproduced Table of Contents in whole or part in any form or This guide offers both inspira- by any means without written tion and information to help permission from the publisher. you plan your Group Tour to Publisher is not responsible for Welcome . 2 errors or omissions. The list- the Richmond region. After ings and advertisements in this Getting Here . 3 learning the basics in our publication do not imply any opening sections, gather ideas endorsement by the publisher or Richmond Region Tourism. Tour Planning . 3 from our listings of events, Printed in Richmond, Va., by sample itineraries, attractions Cadmus Communications, a and more. And before you Cenveo company. Published Out-of-the-Ordinary . 4 for Richmond Region Tourism visit, let us know! by Target Communications Inc. Calendar of Events . 8 Icons you may see ... Art Director - Sarah Lockwood Editor Sample Itineraries. 12 - Nicole Cohen G = Group Pricing Available Cover Photo - Jesse Peters Special Thanks = Student Friendly, Student Programs - Segway of Attractions & Entertainment . 20 Richmond ; = Handicapped Accessible To request information about Attractions Map . 38 I = Interactive Programs advertising, or for any ques- tions or comments, please M = Motorcoach Parking contact Richard Malkman, Shopping . -

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

Treason Trial of Aaron Burr Before Chief Justice Marshall

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1942 Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall Aurelio Albert Porcelli Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Porcelli, Aurelio Albert, "Treason Trial of Aaron Burr before Chief Justice Marshall" (1942). Master's Theses. 687. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/687 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1942 Aurelio Albert Porcelli .TREASON TRilL OF AARON BURR BEFORE CHIEF JUSTICE KA.RSHALL By AURELIO ALBERT PORCELLI A THESIS SUBJfiTTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OJ' mE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA UNIVERSITY .roD 1942 • 0 0 I f E B T S PAGE FOBEW.ARD • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 111 CHAPTER I EARLY LIFE OF llRO:N BURR • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • l II BURR AND JEFF.ERSOB ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 24 III WES!ERN ADVDTURE OF BURR •••••••••••••••••••• 50 IV BURR INDICTED FOR !REASOB •••••••••••••••••••• 75 V !HE TRIAL •.•••••••••••••••• • ••••••••••• • •••• •, 105 VI CHIEF JUSTICE lfA.RSlU.LL AND THE TRIAL ....... .. 130 VII JIA.RSHALJ.- JURIST OR POLITICIAN? ••••••••••••• 142 BIBLIOGRAPHY ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 154 FOREWORD The period during which Thomas Jefferson, John Marshall, and Aaron Burr were public men was, perhaps, the most interest ing in the history of the United States. -

2020 NRHP Additional Documentation

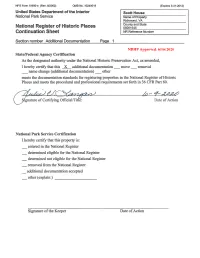

NPS Form 10900-a (Rev. 8/2002) 0MB No. 10240018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior Scott House National Park Service Name of Property Richmond, VA County and State National Register of Historic Places 05001545 Continuation Sheet NR Reference Number Section number Additional Documentation Page 1 NRHP Approved: 6/16/2020 State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _x_ additional documentation _ move _ removal _ name change (additional documentation)_ other meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. gnature of Certifying Official/Tit e: Date of Action National Park Service Certification I hereby certify that this property is: _ entered in the National Register _ determined eligible for the National Register _ determined not eligible for the National Register _ removed from the National Register _ additional documentation accepted _other(explain:) -------~- Signature of the Keeper Date of Action NPS Form 10-900-a (Rev. 8/2002) OMB No. 1024-0018 (Expires 5-31-2012) United States Department of the Interior Scott House Put Here National Park Service Name of Property Richmond, VA County and State National Register of Historic Places 05001545 Continuation Sheet NR Reference Number Section number Additional Documentation Page 2 SCOTT HOUSE ADDITIONAL DOCUMENTATION Prepared by: Christopher V. Novelli Additional Documentation, September 2019 Understanding of the Scott House has greatly increased since the original nomination for the house was written in 2007. -

Charitably Speaking 353 Southern Artery Quincy, MA 02169

June 2013 Charitably Speaking 353 Southern Artery Quincy, MA 02169 A PUBLICATION OF THE MASSACHUSETTS CHARITABLE MECHANIC ASSOCIATION President’s Message I would like to thank the MCMA membership who participated and worked towards our fantastic Triennial at the Royal Sonesta Hotel. Our first silent auction held at that event was a great success, with over $4700 being raised for MCMA’s many missions. I want to thank all who contributed the great items for auction, and also thank all who showed their generosity by purchasing those items. Peter Lemonias and his very conscientious Triennial Committee deserve our particular thanks and appreciation, and we are greatly saddened that one of those men, Carl Wold, was lost to us only weeks after the event. I also want to thank our members for the opportunity to serve as your president, and would like you to know I appreciated all of your congratulations. I look forward to our July Quarterly at the Adams Inn in Neponset and hope to see all of you there. – Rich Adams A Recent Happenings The 72nd Triennial celebration of MCMA was held March 2 at the Royal Sonesta Hotel in Cambridge. Prior to the evening festivities, members and guests enjoyed an escorted tour of the new Art of the Americas Wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, which features a fine collection of Paul Revere’s handiwork. That was followed by a cocktail hour in a room overlooking the Charles River, then dinner and dancing for the remainder of the evening. We did, of course, take time out for the ceremonial passing of the “Revere snuffbox,” the tradition begun in 1852 wherein the snuffbox has been passed from past presidents to the incoming president.