December 2009 Page 1 President's Remarks Once Again It Is Year-End

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Celebrating 30 Years

VOLUME XXX NUMBER FOUR, 2014 Celebrating 30 Years •History of the U.S. Lighthouse Society •History of Fog Signals The•History Keeper’s of Log—Fall the U.S. 2014 Lighthouse Service •History of the Life-Saving Service 1 THE KEEPER’S LOG CELEBRATING 30 YEARS VOL. XXX NO. FOUR History of the United States Lighthouse Society 2 November 2014 The Founder’s Story 8 The Official Publication of the Thirty Beacons of Light 12 United States Lighthouse Society, A Nonprofit Historical & AMERICAN LIGHTHOUSE Educational Organization The History of the Administration of the USLH Service 23 <www.USLHS.org> By Wayne Wheeler The Keeper’s Log(ISSN 0883-0061) is the membership journal of the U.S. CLOCKWORKS Lighthouse Society, a resource manage- The Keeper’s New Clothes 36 ment and information service for people By Wayne Wheeler who care deeply about the restoration and The History of Fog Signals 42 preservation of the country’s lighthouses By Wayne Wheeler and lightships. Finicky Fog Bells 52 By Jeremy D’Entremont Jeffrey S. Gales – Executive Director The Light from the Whale 54 BOARD OF COMMISSIONERS By Mike Vogel Wayne C. Wheeler President Henry Gonzalez Vice-President OUR SISTER SERVICE RADM Bill Merlin Treasurer Through Howling Gale and Raging Surf 61 Mike Vogel Secretary By Dennis L. Noble Brian Deans Member U.S. LIGHTHOUSE SOCIETY DEPARTMENTS Tim Blackwood Member Ralph Eshelman Member Notice to Keepers 68 Ken Smith Member Thomas A. Tag Member THE KEEPER’S LOG STAFF Head Keep’—Wayne C. Wheeler Editor—Jeffrey S. Gales Production Editor and Graphic Design—Marie Vincent Copy Editor—Dick Richardson Technical Advisor—Thomas Tag The Keeper’s Log (ISSN 0883-0061) is published quarterly for $40 per year by the U.S. -

I Can Live No Longer

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from them ic ro film master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margin^ and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note win indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of die book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313/761-4700 800/521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ••I CAN LIVE NO LONGER HERE" ELIZABETH WIRT'S DECISION TO BUY A NEW HOUSE by Jill Haley A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the University of Delaware in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Early American Culture Summer 1995 Copyright 1995 Jill Haley All Rights Reserved Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Charitably Speaking 353 Southern Artery Quincy, MA 02169

June 2013 Charitably Speaking 353 Southern Artery Quincy, MA 02169 A PUBLICATION OF THE MASSACHUSETTS CHARITABLE MECHANIC ASSOCIATION President’s Message I would like to thank the MCMA membership who participated and worked towards our fantastic Triennial at the Royal Sonesta Hotel. Our first silent auction held at that event was a great success, with over $4700 being raised for MCMA’s many missions. I want to thank all who contributed the great items for auction, and also thank all who showed their generosity by purchasing those items. Peter Lemonias and his very conscientious Triennial Committee deserve our particular thanks and appreciation, and we are greatly saddened that one of those men, Carl Wold, was lost to us only weeks after the event. I also want to thank our members for the opportunity to serve as your president, and would like you to know I appreciated all of your congratulations. I look forward to our July Quarterly at the Adams Inn in Neponset and hope to see all of you there. – Rich Adams A Recent Happenings The 72nd Triennial celebration of MCMA was held March 2 at the Royal Sonesta Hotel in Cambridge. Prior to the evening festivities, members and guests enjoyed an escorted tour of the new Art of the Americas Wing of the Museum of Fine Arts, which features a fine collection of Paul Revere’s handiwork. That was followed by a cocktail hour in a room overlooking the Charles River, then dinner and dancing for the remainder of the evening. We did, of course, take time out for the ceremonial passing of the “Revere snuffbox,” the tradition begun in 1852 wherein the snuffbox has been passed from past presidents to the incoming president. -

Faneuil Hall Stands at the Eastern Edge of Dock Square (Intersection of Congress and North Streets) in Boston, Massachusetts

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATESDEPARTMEWOF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC Paneuil Hall AND/OR COMMON Paneuil Hall LOCATION STREET & NUMBER Dock Sauare fjlaneuil Hall —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY, TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 0? «» RifF-Fnllr A9C HCLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE —DISTRICT X_PUBLIC XoCCUPlEO —AGRICULTURE X.MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) —PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED ^—COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ ENTERTAINMENT _ RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS X.YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO _ MILITARY XpIHER DUbllC mAATLinir nAl T QOWNER OF PROPERTY NAME City of Boston, Office of the Mayor STREET & NUMBER New City Hall CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts HLOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEOS. ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Suffolk County Court House, Somerset Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts Q REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Historic American Buildings Survey DATE 1935, 1937 X-FEDERAL _STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY. TOWN " " STATE Washington. D.C. DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X-ORIGINALSITE —GOOD _RUINS X-ALTERED —MOVED DATE- X_FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Faneuil Hall stands at the eastern edge of Dock Square (intersection of Congress and North Streets) in Boston, Massachusetts. -

Newsletter the Society of Architectural Historians

NEWSLETTER THE SOCIETY OF ARCHITECTURAL HISTORIANS FEBRUARY 1985 VOL. XXIX NO. I SAH NOTICES CALL FOR PAPERS 1985 Annual Meeting-Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (April 17- The next Victorians Institute Meeting will be held at 21). The final printed program (with pre-registration form Georgetown University, Washington, D.C. on October 4th and hotel reservation card) was sent to the membership in and 5th, 1985. The conference topic will be "The Uses of the January. Members are reminded that this program should be Past in Victorian Culture." Papers should be submitted to brought with them to the meeting in April. Since this prom the 1985 conference chairman John Pfordresher, at the ises to be a well-attended meeting, members are urged to Department of English, Georgetown University, Washing pre-register as soon as possible. ton, D.C. 20057. The deadline for submissions is June lst of 1985 . 1986 Annual Meeting-Washington, DC (April 2-6). General The twelfth annual Carolinas Symposium on British chairman of the meeting is Osmund Overby of the U niver Studies will be held at East Tennessee State University on sity of Missouri. Antoinette Lee, Columbia Historical Soci October 12-13, 1985 . The program invites proposals for ety, is serving as local chairman. A call for papers will be individual papers, panel discussions, and full sessions in all published in the April Newsletter. Please submit suggestions aspects of British Studies. A $100 prize will be awarded for for sessions to Osmund Overby in care of the SAH office, the best paper from among those read at the Symposium Suite 716, 1700 Walnut Street, Philadelphia, PA 19103- and submitted to the evaluation committee by the following 6085 . -

Massachusetts

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Massachusetts COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Suffolk INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER (Type all entries — complete applicable sections) COMMON: Mfl.ggfl.rhll.CiP>tT-.S Hospital AND/OR HISTORIC: STREET AND NUMBER: Fruit Street CITY OR TOWN: Boston CATEGORY ACCESSIBLE OWNERSHIP STATUS (Check One) TO THE PUBLIC 10oi arf Building PublitAequisition: Occupied Yes: S Restricted D Site Structure £S Private [~| In Process Unoccupied n Unrestricted D Object Q Both | | Being Considered Preservation work in progress D No U PRESENT USE ("Check One or Afore as Appropriate) ID I I Agriculture! I I Government D Pork CD Transportation I I Comments t£ I | Commercial I I Industrial CD Private Residence 2§0ther (.Specify) h- [~| Educational CD Military [~| Religious Hospital «/» [~l Entertoinment [~l Museum I | Scientific Z OWNER'S NAME: otasBlo Massachusetts General Hospital UJ STREET AND NUMBER: UJ t/> COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: Registry of Deeds, Suffolk Cou STREET AND NUMBER: xsicrmoo CITY OR TOWN: r-^- ............................................—————.. .....^.^.^,,,.,.,,.,.,.... Tl tl_E OF SURVEY: —HI fitorir. Amf>rigan Buildings Survey (3 photos) DATE OF SURVEY: Federal Q State Q County Local DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS: Division of Prints and Photographs Library nf STREETe-mc-e-T ANDAKIPN NUMBER:K.I i 11 ^ n c- n . ^~^ * ' " CITY OR TOWN: Washington 205^0 D. C. 7. (Check One) Excellent O Good Fair [ I Deteriorated Ruins I I Unexposed CONDITION (Check One) (Check One) Altered d] Unaltered Moved [f5 Original Site DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (if known) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Built of granite in coursed arhlar, the Massachusetts General Hospital is a long oblong structure, two stories over elevated, rusticated basement, with a central projecting and pedimentea giant Ionic portico, two wings, anu a hipped roof. -

Nomination Form

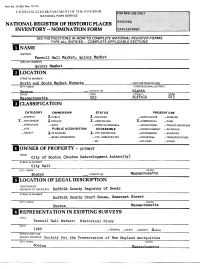

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THH INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS I NAME HISTORIC Faneuil Hall Market; Quincy Market AND/OR COMMON Quincy Market LOCATION STREET & NUMBER North and South Market Streets _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT ftocH'.nn __ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Suffolk 025 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT X_PUBLIC X_OCCUPIED _AGRICULTURE _MUSEUM X—BUILDING(S) X-PRIVATE X_UNOCCUPIED ^COMMERCIAL _PARK —STRUCTURE —BOTH _WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE _ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT XJN PROCESS X—YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC _BEING CONSIDERED _YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: [OWNER OF PROPERTY - primary City of Boston (Boston Redevelopment Authority) STREET & NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEos.ETc. Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREET & NUMBER Suffolk County Court House, Somerset Street CITY, TOWN Boston [1 REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Faneuil Hall Market: Historical Study DATE 1969 — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY J&.OCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Society for the Preservation of New England Antiquities CITY. TOWN STATE BostOn DESCRIPTION CONDITION -

Some Aspects Profession of the Development of the Architectural in Boston Between 1800 and 1830 L

Some Aspects of the Development of the Architectural Profession in Boston Between 1800 and 1830 l JACK QUINAN* T he distinction between house- The earliest architectural school in Bos- wrights and gentlemen amateurs in ton has been attributed by several scholars 1 American architecture of the to Asher Benjamin at a date close to 1805.2 eighteenth century standsin sharpcontrast Unfortunately, the school has never been to the architectural profession as it de- adequately documented. Benjamin had veloped during the nineteenth century. In a submitted the following proposal for an little more than fii years “polite” ar- architectural school to the Windsor [Ver- chitecture ceased to be the occasional mont] Gazette of 5 January 1802. which preoccupationof a few educatedgentlemen seemsto have led Talbot Hamlin and Roger and emerged as a true profession, that is, Hale Newton to conclude that Benjamin one in which its practitioners could support subsequently established a school in Bos- themselves by designing buildings. The ton: change was momentous, and we may well ask how it came about. The topic is broad, To Young Carpenters. Joiners and All of course, and this paper shag be confmed Others concerned in the Art of building: to events in Boston with the hope that -The subscriberintends to opena School of Architectureat hishouse in Windsor, the similar studiesof other American cities will 20th of February next-at which will be soon follow. taughtThe Five Ordersof Architecture,the In a period of intense activity between Proportionsof Doors, Windows and Chim- 1800 and 1830 a number of architectural neypieces,the Constructionof Stairs, with schools, professional organizations, ar- their ramp and twist Rails, the method of farmitg timbers, lengthand backing of Hip chitectural libraries, and other related rafters,the tracingof groinsto AngleBrac- phenomena, materialized and provided the kets, circular soffitsin circularwalls; Plans, groundwork for the new profession in Bos- Elevationsand Sectionsof Houses,with all ton. -

Alexander Parris's Engineering Projects

SIA New England Chapters Newsletter 17 An Architect and Engineer in the Early Nineteenth Century: Alexander Parris's Engineering Projects In the first half of the nineteenth century, a number America. Moreover, given the dearth of architects, of prominent architects also practiced civil engi Parris had to teach himself how to draw and neering and called themselves "architect and engi design. He got ideas for designs and structural neer." Yet with one or two exceptions, their engi systems from traveling - visiting important new neering work has been overlooked by historians. buildings - and architectural books, including This is the case for the New England native British building manuals such those by Batty Alexander Parris (1780-1852), one of the most Langley and Peter Nicholson. He eventually important architect-engineers of the early nine owned a large library of architectural and engi teenth century. neering books. Today Parris is known only for his architec ture - his monumental, classical-style granite buildings such as St. Paul's Church, Boston (1819- 20); Quincy Market and stores, Boston (1824-26); and the Stone Temple, Quincy (1827-28). Yet dur ing his professional career, Parris spent less time practicing architecture than he did working as an engineer. The period he practiced as an architect principally lasted only about ten years, from around 1818 to 1828. Then, from the late 1820s to the end of his life, Parris worked mainly (although not exclusively) on engineering projects, which Structural engineering projects included gunpowder magazines, a rope factory, lighthouses, beacons, seawalls, and dry docks. Although he had an active architectural practice in The client for most of these structures was the fed the 1820s, at the end of the decade, architectural eral government. -

1988 NHL Nomination

0MB No. 10,4--0018 ~:.:.~i'~~i-R. - 11/5/ ~g ~f2-++f &/~ /&i United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations of eligibility for individual properties or districts. See instructions in Guidelines for Completing National Register Forms (National Register Bulletin 16). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the requested information. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "NIA" for "not applicable." For functions, styles, materials, and areas of significance. enter only the categories and subcategories listed in the instructions. For additional space use continuation sheets (Form 10.900a). Type all entries. 1. Name of Property historic name Governor's ~~nsion other names/site number Executive Mansion 2. Location street & number Capitol Square N/ U not for publication ci , town state 1rginia county 3. Classification Ownership of Property Category of Property Number of Resources within Property Oprivate [yJ building(s) Contributing Noncontributing D public-local 0dtstrict 3 1 buildings W public-State Osite 0 0 sites 0 public-Federal D structure 0 0 structures Oobject 0 0 objects 3 1 Total Name of related multiple property listing: Number of contributing resources ~reviously N/A listed in the National Register _____ 4. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I he<eby certify that this 00 nomination D request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFA Part 60. -

Cumentation Fonn Light Stations in the United State NPS Form 10-900-B

USDI/NPS NRHP Multiple Propert~ cumentation Fonn Light Stations in the United State Page 1 NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Fonn This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Fonn (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing Light Stations of the United States B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) Federal Administration of Lighthouses, U.S. Lighthouse Service, 1789-1952 Architecture & Engineering, U.S. Lighthouse Construction Types, Station Components, Regional Adaptations and Variations, 1789 -1949 Evolution of Lighthouse Optics, 1789 -1949 Significant Persons, U.S. Lighthouse Service, 1789 -1952 C. Form Prepared by name/title Edited and formatted by Candace Clifford, NCSHPO Consultant to the NPS National Maritime Initiative, National Register, History and Education Program. Based on submissions by Ralph Eshelman under cooperative agreement with U.S. Lighthouse Society, and Ross Holland under cooperative agreement with National Trust for Historic Preservation Also reviewed, reedited, and reformatted by Ms. Kebby Kelley and Mr. David Reese, Office of Civil Engineering, Environmental Management Division, US Coast Guard Headquarters, and Jennifer Perunko, NCSHPO consultant to the NPS National Maritime Initiative, National Register, History and Education Program. -

December 2010 Page 1

President's Message I want to thank everyone who attended our October Quarterly Meeting, and I hope those three dozen or so members who were able to take the time to also travel to Methuen to visit the Music Hall agree that the trip was well worthwhile. Both the building and the organ are awesome, and I'm glad you were able to enjoy them. At the meeting we were able to distribute our new lapel pins, and I hope you are pleased with the result and will wear them proudly. Lastly, it is that time of year again where we must ask all members to consider a donation to help support MCMA. Donations are tax-deductible, and they are important to us, so please do what you can. I cannot believe my first year as President is almost over. It has been very enjoyable and I am enthused about the future. I would like to thank all those that have helped me and all those that have given me their support. Bill Anderson Recent Happenings Our October Quarterly was, as promised, held at the China Blossom Restaurant in North Andover, where we enjoyed a very good (and very diverse) buffet meal. In addition to our normal business items, President Anderson distributed the new MCMA lapel pins to all members attending. [We thank President Anderson, Vice President Rich Adams, Past President Bill Jutila and Trustees Arthur Anthony and Chuck Sulkala for their work in coordinating the design and production of these pins.] Membership Committee Chairman Joseph Bellomo reported that his committee, having reviewed the application of Mr.