Buen Vivir: a Path to Reimagining Corporate Social Responsibility in Mexico After COVID-19

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ancient Mexico: the Legacy of the Plumed Serpent

LACMA | Evenings for Educators | April 17, 2012 Ancient Mexico: The Legacy of the Plumed Serpent _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ The greatness of Mexico is that its past is always alive . Mexico exists in the present, its dawn is occurring right now, because it carries with it the wealth 1 of a living past, an unburied memory. —Carlos Fuentes MUCH OF THE HISTORY AND TRADITIONS OF MESOAMERICA, The system of pictographic communication a cultural region encompassing most of Mexico and and its accompanying shared art style was an northern Central America, can be traced through ingenious response to the needs of communities a pictorial language, or writing system, that was whose leaders spoke as many as twelve different introduced around AD 950. By 1300 it had been languages. Beginning in the tenth century, widely adopted throughout Southern Mexico. Southern Mexico was dominated by a confeder- This shared art style and writing system was used acy of city-states (autonomous states consisting to record and preserve the history, genealogy, and of a city and surrounding territories). Largely mythology of the region. It documents systems controlled by the nobility of the Nahua, Mixtec, of trade and migration, royal marriage, wars, and and Zapotec peoples, these city-states claimed records epic stories that continue to be passed on a common heritage. They believed that their through a pictorial and oral tradition today. kingdoms had been founded by the hero Quetzalcoatl, the human incarnation of the This pictorial language was composed of highly Plumed Serpent. They shared a culture, world- conventionalized symbols characterized by an view, and some religious practices but operated almost geometric precision of line. -

Aztec Culture Education Update

Aztec Culture Education Committee Ideas Report Draft August 2018 ORIGINAL CHARGE/FRAMEWORK A committee of cross campus partners including faculty, staff and students was formed at the end of the 2016- 2017 academic year to work on and develop a comprehensive Aztec culture educational plan. As a result of the committee meetings, a number of proposed initiatives were identified. The charge of the group and the basis of the conversations have revolved around fulfilling prior commitments made by the campus, as an example: Associated Students Referendum Spring 2008, passed Implementation of an Aztec Culture Project. The Project will include three elements intended to promote historically accurate portrayals of the Aztec Culture: new botanical gardens around the campus that include indigenous plantings from areas where the Aztecs thrived, a glass-mosaic mural that depicts historically accurate images portraying the origins of the Aztec Culture, and educational programs about the Aztec Culture that would be offered to all new SDSU students As the committee incorporated the recognition of the University’s relationship to local Indian groups as well as other indigenous groups from Mexico that comprise the larger University community. To begin prioritizing ideas and potential campus efforts, the following framework has been created from the current committee’s discussions, to categorize the overarching topical areas and objectives identified to date: San Diego State University will enrich the environment and deepen campus learning, both inside and outside the classroom, by enhancing Aztec Culture Education knowledge and understanding by strategically: • Expanding opportunities for scholarship regarding Aztec Culture, as well as local indigenous and Native American groups, through innovative courses, experiences, and engagement. -

Animal Economies in Pre-Hispanic Southern Mexico 155

The The Recognition of the role of animals in ancient diet, economy, politics, and ritual is vital to understanding ancient cultures fully, while following the clues available from Archaeobiology 1 animal remains in reconstructing environments is vital to understanding the ancient relationship between humans and the world around them. In response to the growing interest in the field of zooarchaeology, this volume presents current research from across the many cultures and regions of Mesoamerica, dealing specifically with the Archaeology most current issues in zooarchaeological literature. Geographically, the essays collected here index the The Archaeology of different aspects of animal use by the indigenous populations of the entire area between the northern borders of Mexico and the southern borders of lower Central America. This includes such diverse cultures as the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Central American Indians. The time frame of the volume extends from the Preclassic to recent times. The book’s chapters, written by experts in the field of Mesoamerican Mesoamerican Animals of Mesoamerican zooarchaeology, provide important general background on the domestic and ritual use of animals in early and classic Mesoamerica and Central America, but deal also with special aspects of human–animal relationships such as early domestication and symbolism of animals, and important yet edited by Christopher M. Götz and Kitty F. Emery otherwise poorly represented aspects of taphonomy and zooarchaeological methodology. Christopher M. Götz is Profesor-Investigador (lecturer & researcher), Facultad de Ciencias Antropológicas, UADY, Mexico. Kitty F. Emery is Associate Curator of Environmental Archaeology, Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, USA. Animals “A must for those interested in the interaction of human and animals in Mesoamerica or elsewhere. -

Ellen Hoobler Primary Source Materials on Oaxacan Zapotec Urns

FAMSI © 2008: Ellen Hoobler Primary Source Materials on Oaxacan Zapotec Urns from Monte Albán: A New Look at the Fondo Alfonso Caso and other archives in Mexico Research Year: 2007 Culture: Zapotec, Mixtec Chronology: Preclassic - Classic Location: México D.F. and Pachuca, Hildago Site: Various archives at UNAM, MNAH, INAH, etc. Table of Contents Abstract Resumen Introduction Background Objectives Methodology Biographical Information Overview of the Materials Biblioteca "Juan Comas", Instituto Investigaciones Antropológicas Biblioteca Nacional de Antropología e Historia (BNAH) Instituto Nacional Indigenista INAH – Archivo Técnico Photo Collections Other Possible Sources of Information on the Monte Albán Excavations Conclusion Acknowledgements List of Figures Sources Cited Appendix A – Chronology of Alfonso Caso's Life and Career Appendix B – Research Resources Abstract I proposed a two-week trip to review the archival materials of the Fondo Alfonso Caso in Mexico City. Within the Fondo, essentially a repository of the Mexican archaeologist Caso’s papers, I was particularly interested in works relating to his excavations of Zapotec tombs at Monte Albán, in the modern-day state of Oaxaca, in México. The Fondo’s collection is distributed among three locations in Mexico City, at the Biblioteca Nacional de Antropología e Historia (BNAH), housed in the Museo Nacional de Antropología e Historia; at the Instituto de Investigaciones Antropológicas (IIA) of the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM); and at the former Instituto Nacional Indigenista (now Comisión Nacional para el Desarrollo de Pueblos Indígenas, CNDPI). My main goal in reviewing the materials of the Fondo Alfonso Caso was to obtain additional notes and images relating to Caso’s excavations in Monte Albán in the 1930s and ‘40s. -

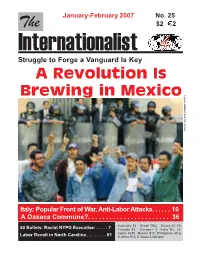

Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key a Revolution Is

January-February 2007 No. 25 The $2 2 Internationalist Struggle to Forge a Vanguard Is Key A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico Times Addario/New Lynsey York Italy: Popular Front of War, Anti-Labor Attacks. 10 A Oaxaca Commune?. 36 Australia $4, Brazil R$3, Britain £1.50, 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Execution . 7 Canada $3, Europe 2, India Rs. 25, Japan ¥250, Mexico $10, Philippines 30 p, Labor Revolt in North Carolina . 61 S. Africa R10, S. Korea 2,000 won 2 The Internationalist January-February 2007 In this issue... Mexico: The UNAM A Revolution Is Brewing in Mexico .......... 3 Strike and the Fight for Workers 50 Bullets: Racist NYPD Cop Execution, Revolution Again ........................................................ 7 March 2000 US$3 Mobilize Workers Power to Free Mumia For almost a year, tens of Abu-Jamal! .....................'--························ 9 thousands of students occupied the largest university Italy: Popular Front of Imperialist in Latin America, facing War and Anti-Labor Attacks .................... 10 repression by both the PAI government and the PAD Break Calderon's "Firm Hand" With opposition. This 64-page special supplement tells the Workers Struggle .................................. 15 story of the strike and documents the intervention State of Siege in Oaxaca, Preparations of the Grupo in Mexico City ....................................... 17 lnternacionalista. November 25 in Oaxaca: Order from/make checks payable to: Mundial Publications, Box 3321, Church Street Station, NewYork, New York 10008, U.S.A. Night of the Hyenas .............................. 20 Oaxaca Is Burning: Showdown in Mexico ........................... 21 Visit the League for the Fourth International/ Internationalist Group on the Internet The Battle of Oaxaca University ............. 23 http://www.internationalist.org A Oaxaca Commune? ..................... -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Soy de Zoochina: Zapotecs Across Generations in Diaspora Re-creating Identity and Sense of Belonging Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3242z14x Author Nicolas, Brenda Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Soy de Zoochina: Zapotecs Across Generations in Diaspora Re-creating Identity and Sense of Belonging A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies by Brenda Nicolas 2017 © Copyright by Brenda Nicolas 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Soy de Zoochina: Zapotecs Across Generations in Diaspora Re-creating Identity and Sense of Belonging by Brenda Nicolas Master of Arts in Chicana and Chicano Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Leisy Janet Abrego, Chair Using a critical hemispheric indigenous framework to analyze my interviews and participant observation work, I argue that indigenous women’s challenges to expected gender norms reinforce and solidify comunalidad and sense of belonging and being indigenous to their community. Based on qualitative and ethnographic fieldwork in Los Angeles I show that belonging to Zoochina and being Zoochinense is taught and practiced in traditional dances, being in the Oaxacan brass band, and as a member of the hometown association. To do this, I consider the indigenous Oaxacan conception of collective community life— comunalidad— in order to understand current forms of community participation in Los Angeles (Luna 2013). I coin the term “transnational comunalidad,” of which I define as, the indigenous ideology and practice of communal belonging and being across generations in diaspora. -

Mediating Indigenous Identity: Video, Advocacy, and Knowledge in Oaxaca, Mexico

University of Kentucky UKnowledge University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 MEDIATING INDIGENOUS IDENTITY: VIDEO, ADVOCACY, AND KNOWLEDGE IN OAXACA, MEXICO Laurel Catherine Smith University of Kentucky Right click to open a feedback form in a new tab to let us know how this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Smith, Laurel Catherine, "MEDIATING INDIGENOUS IDENTITY: VIDEO, ADVOCACY, AND KNOWLEDGE IN OAXACA, MEXICO" (2005). University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations. 359. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/gradschool_diss/359 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at UKnowledge. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Kentucky Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UKnowledge. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Laurel Catherine Smith The Graduate School University of Kentucky 2005 MEDIATING INDIGENOUS IDENTITY: VIDEO, ADVOCACY, AND KNOWLEDGE IN OAXACA, MEXICO ______________________________________ ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION ______________________________________ A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of Kentucky By Laurel Catherine Smith Lexington, Kentucky Co-Directors: Dr. John Paul Jones III, Professor of Geography and Dr. Susan Roberts, Professor of Geography Lexington, Kentucky 2005 Copyright © Laurel Catherine Smith 2005 ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION MEDIATING INDIGENOUS IDENTITY: VIDEO, ADVOCACY, AND KNOWLEDGE IN OAXACA, MEXICO In the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca, many indigenous communities further their struggles for greater political and cultural autonomy by working with transnational non- governmental organizations (NGOs). Communication technology (what I call comtech) is increasingly vital to these intersecting socio-spatial relations of activism and advocacy. -

Proquest Dissertations

Zapotec language shift and reversal in Juchitan, Mexico Item Type text; Dissertation-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Saynes-Vazquez, Floria E. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 04/10/2021 04:34:13 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/289854 INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overiaps. ProQuest Information and Leaming 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 ZAPOTEC LANGUAGE SHIFT AND REVERSAL IN JUCHITAN. MEXICO by Fiona E. -

The Hall of Mexico and Central America

The Hall of Mexico and Central America Teacher’s Guide See inside Panel 2 Introduction 3 Before Coming to the Museum 4 Mesoamericans in History 5-7 At the Museum 7 Related Museum Exhibitions 8 Back in the Classroom Insert A Learning Standards Bibliography and Websites Insert B Student Field Journal Hall Map Insert C Map of Mesoamerica Time Line Insert D Photocards of Objects Maya seated dignitary with removable headdress Introduction “ We saw so many cities The Hall of Mexico and Central America displays an outstanding collection of and villages built in the Precolumbian objects. The Museum’s collection includes monuments, figurines, pottery, ornaments, and musical instruments that span from around 1200 B.C. water and other great to the early 1500s A.D. Careful observation of each object provides clues about towns on the dry land, political and religious symbols, social and cultural traits, and artistic styles and that straight and characteristic of each cultural group. level causeway going WHERE IS MESOAMERICA? toward Mexico, we were Mesoamerica is a distinct cultural and geographic region that includes a major amazed…and some portion of Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. The geographic soldiers even asked borders of Mesoamerica are not located like those of the states and countries of today. The boundaries are defined by a set of cultural traits that were shared by whether the things that all the groups that lived there. The most important traits were: cultivation of corn; a we saw were not a sacred 260-day calendar; a calendar cycle of 52 years; pictorial manuscripts; pyramid dream." structures or sacred “pyramid-mountains;” the sacred ballgame with ball courts; ritual bloodletting; symbolic imagery associated with the power of the ruler; and Spanish conquistador Bernal Díaz temples, palaces, and houses built around plazas. -

Ripples of Modernity: Language Shift and Resistance in the Valley of Etla

Ripples of Modernity: Language Shift And Resistance in The Valley of Etla Mackenzie McDonald Wilkins Senior Honors Thesis University of Michigan Anthropology 2013 Advisors: David Frye, Barbra Meek, Erik Mueggler Copyright ¤ by Mackenzie McDonald Wilkins 1 Table of Contents Introduction: Tizá and Two Zapotec Communities Chapter 1: Language and Ethnicity in the Changing Lives of Zautecos and Mazaltecos Chapter 2: Education and Language Shift Yesterday and Today Chapter 3: Ripples of Modernity: Competing Ideologies and Multiple Discourses Chapter 4: Revitalization and Resistence: Discourse and Practice in Two Pro-Indígena Efforts Conclusion: Works Cited: 2 Introduction: Tizá and Two Zapotec Communities Zapotec is sung. It’s practically a language in song—Lydia, age 51, Zautla El Zapoteco es cantado. Practicamente es una lengua cantada. For us Zapotecs there are two world: the world of Spanish and the West and our world. So I, for example, dream in Zapotec, not in Spanish. They’re two differnt things. Different worlds—Felipe Froilán, Mazaltepec Para nosotros los Zapotecso son dos mundos: el mundo del Español y Occidental y nuestro mundo. Entonces, yo por ejemplo sueño en Zapoteco, no sueño en Español. Son como dos cosas diferentes. Son dos mundos. Two Zapotec Communities: As the smoggy dusk fell upon the Central de Abastos, Oaxaca City’s biggest colectivo taxii hub, people rushed to their respective taxi stops. I meandered through the crowds, nearly stepping into a large hole in the sidewalk, until I found the stop for Zautla. There was a long line but no taxi. I counted ten people in front of me, but did not recognize any of them. -

Incompatible Worlds? Protestantism and Costumbre in the Zapotec Villages of Northern Oaxaca1

doi:10.7592/FEJF2012.51.gross INCOMPATIBLE WORLDS? PROTESTANTISM AND COSTUMBRE IN THE ZAPOTEC VILLAGES OF NORTHERN OAXACA1 Toomas Gross Abstract: In recent decades, Protestant population has grown rapidly in most Latin American countries, including Mexico. The growth has been particularly fast in rural and indigenous areas, where Protestantism is often claimed to trigger profound socio-cultural changes. This article discusses the impact of Protestant growth on customs, collective practices and local identities using the example of indigenous Zapotec communities of the Sierra Juárez in northern Oaxaca. Drawing on the author’s intermittent fieldwork in the region since 1998, most recently in 2012, the article first scrutinises some of the recurring local percep- tions of Protestant growth in the Sierra Juárez and their impact on communal life. Particular attention will be paid to converts’ break with various customary practices pertaining to what locally is referred to as usos y costumbres. The article will then critically revise the claims about the culturally destructive influence of Protestantism, suggesting that the socio-cultural changes in contemporary indigenous communities of Oaxaca may actually be caused by more general mod- ernising and globalising forces, and that the transformative role of Protestantism is often exaggerated. Key words: Protestantism, indigenous customs, culture, identity, Oaxaca, Za- potecs INTRODUCTION Since the 1960s, Protestant churches – various Pentecostal and neo-Pentecostal churches in particular – have grown rapidly in Latin America. The alleged corollaries of this growth – converts’ emphasis on success and prosperity, more individualist worldview, and more emotional relationship with one’s faith – have often been considered by scholars as vehicles of much broader and deeper social and cultural changes than the mere fragmentation of the ‘religious field’ or the makeover of individual converts’ lives. -

Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage Past, Present and Future Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage Carola Hein Editor

Carola Hein Editor Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage Past, Present and Future Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage Carola Hein Editor Adaptive Strategies for Water Heritage Past, Present and Future Editor Carola Hein Faculty of Architecture and the Built Environment Technical University Delft Delft, Zuid-Holland, The Netherlands ISBN 978-3-030-00267-1 ISBN 978-3-030-00268-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-00268-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2019934522 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and the Author(s) 2020. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc- nd/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this license to share adapted material derived from this book or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. This work is subject to copyright.