Gitanjali Once Again

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dus Mahavidyas

Newsletter Archives www.dollsofindia.com Rabindranath Tagore – A Beacon of Light Copyright © 2011, DollsofIndia Jeebono Jokhon Shukaey Jaey When the heart is hard and parched up Korunadharaey Esho come upon me with a shower of mercy. Shokolo Madhuri Lukaey Jaey When grace is lost from life Geetoshudharoshe Esho come with a burst of song. Kormo Jokhon Probolo Aakar When tumultuous work raises its din Goroji Uthiya Dhake Chari Dhar on all sides shutting me out from beyond, Hridoyprante, Hey Jibononath come to me, my lord of silence Shanto Chorone Esho with thy peace and rest. Aaponare Jobe Koriya Kripon When my beggarly heart sits crouched Kone Pore Thake Deenohino Mon shut up in a corner, Duraar Khuliya, Hey Udaaro Nath break open the door, my king Raajoshomarohe Esho and come with the ceremony of a king Bashona Jokhon Bipulo Dhulaey When desire blinds the mind Ondho Koriya Obodhe Bhulaey with delusion and dust Ohe Pobitro, Ohey Onidro O thou holy one, thou wakeful Rudro Aaloke Esho come with thy light and thy thunder - a poem from the collection - Transalated by Rabindranath Tagore "Gitanjali" Original writing of Rabindranath Tagore Courtesy Gitabitan.net This song was sung by Rabindranath Tagore for Mahatma Gandhi, on September 26, 1932, right after Gandhi broke his fast unto death, undertaken to force the colonial British Government to abjure its decision of separation of the lower castes as an electorate in India. Tagore was and will remain one of the greatest poets and philosophers the world has ever seen. His contribution to Indian literature, music, arts and drama endeared him not only to Bengalis but to Indians and the world at large. -

Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay

BOOK DESCRIPTION AUTHOR " Contemporary India ". Nandan Gupta. `Prak-Bibar` Parbe Samaresh Basu. Nimai Bandyopadhyay. 100 Great Lives. John Cannong. 100 Most important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 100 Most Important Indians Today. Sterling Special. 1787 The Grand Convention. Clinton Rossiter. 1952 Act of Provident Fund as Amended on 16th November 1995. Government of India. 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action. Indian Institute of Human Rights. 19e May ebong Assame Bangaliar Ostiter Sonkot. Bijit kumar Bhattacharjee. 19-er Basha Sohidera. Dilip kanti Laskar. 20 Tales From Shakespeare. Charles & Mary Lamb. 25 ways to Motivate People. Steve Chandler and Scott Richardson. 42-er Bharat Chara Andolane Srihatta-Cacharer abodan. Debashish Roy. 71 Judhe Pakisthan, Bharat O Bangaladesh. Deb Dullal Bangopadhyay. A Book of Education for Beginners. Bhatia and Bhatia. A River Sutra. Gita Mehta. A study of the philosophy of vivekananda. Tapash Shankar Dutta. A advaita concept of falsity-a critical study. Nirod Baron Chakravarty. A B C of Human Rights. Indian Institute of Human Rights. A Basic Grammar Of Moden Hindi. ----- A Book of English Essays. W E Williams. A Book of English Prose and Poetry. Macmillan India Ltd.. A book of English prose and poetry. Dutta & Bhattacharjee. A brief introduction to psychology. Clifford T Morgan. A bureaucrat`s diary. Prakash Krishen. A century of government and politics in North East India. V V Rao and Niru Hazarika. A Companion To Ethics. Peter Singer. A Companion to Indian Fiction in E nglish. Pier Paolo Piciucco. A Comparative Approach to American History. C Vann Woodward. A comparative study of Religion : A sufi and a Sanatani ( Ramakrishana). -

MA BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department Of

M.A. BENGALI SYLLABUS 2015-2020 Department of Bengali, Bhasa Bhavana Visva Bharati, Santiniketan Total No- 800 Total Course No- 16 Marks of Per Course- 50 SEMESTER- 1 Objective : To impart knowledge and to enable the understanding of the nuances of the Bengali literature in the social, cultural and political context Outcome: i) Mastery over Bengali Literature in the social, cultural and political context ii) Generate employability Course- I History of Bengali Literature (‘Charyapad’ to Pre-Fort William period) An analysis of the literature in the social, cultural and political context The Background of Bengali Literature: Unit-1 Anthologies of 10-12th century poetry and Joydev: Gathasaptashati, Prakitpoingal, Suvasito Ratnakosh Bengali Literature of 10-15thcentury: Charyapad, Shrikrishnakirtan Literature by Translation: Krittibas, Maladhar Basu Mangalkavya: Biprodas Pipilai Baishnava Literature: Bidyapati, Chandidas Unit-2 Bengali Literature of 16-17th century Literature on Biography: Brindabandas, Lochandas, Jayananda, Krishnadas Kabiraj Baishnava Literature: Gayanadas, Balaramdas, Gobindadas Mangalkabya: Ketakadas, Mukunda Chakraborty, Rupram Chakraborty Ballad: Maymansinghagitika Literature by Translation: Literature of Arakan Court, Kashiram Das [This Unit corresponds with the Syllabus of WBCS Paper I Section B a)b)c) ] Unit-3 Bengali Literature of 18th century Mangalkavya: Ghanaram Chakraborty, Bharatchandra Nath Literature Shakta Poetry: Ramprasad, Kamalakanta Collection of Poetry: Khanadagitchintamani, Padakalpataru, Padamritasamudra -

How to Cite Complete Issue More Information About This Article

Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara ISSN: 2469-0783 [email protected] Fundación MenteClara Argentina Basu, Ratan Lal Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, vol. 3, no. 2, 2018, April-September 2019, pp. 7-30 Fundación MenteClara Argentina DOI: https://doi.org/10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Available in: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=563560859001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System Redalyc More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America and the Caribbean, Spain and Journal's webpage in redalyc.org Portugal Project academic non-profit, developed under the open access initiative Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension Ratan Lal Basu Artículos atravesados por (o cuestionando) la idea del sujeto -y su género- como una construcción psicobiológica de la cultura. Articles driven by (or questioning) the idea of the subject -and their gender- as a cultural psychobiological construction Vol. 3 (2), 2018 ISSN 2469-0783 https://datahub.io/dataset/2018-3-2-e43 TAGORE-OCAMPO RELATION, A NEW DIMENSION RELACIÓN TAGORE-OCAMPO, UNA NUEVA DIMENSIÓN Ratan Lal Basu [email protected] Presidency College, Calcutta & University of Calcutta, India. Cómo citar este artículo / Citation: Basu R. L. (2018). « Tagore-Ocampo relation, a new dimension». Revista Científica Arbitrada de la Fundación MenteClara, 3(2) abril-septiembre 2018, 7-30. DOI: 10.32351/rca.v3.2.43 Copyright: © 2018 RCAFMC. Este artículo de acceso abierto es distribuido bajo los términos de la licencia Creative Commons Attribution-Non Commercial (by-cn) Spain 3.0. Recibido: 23/05/2018. -

2 Tagore Looks East

NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 2 TAGORE LOOKS EAST Rabindranath Tagore in Indonesia, 1927 Sukanta Chaudhuri NALANDA-SRIWIJAYA CENTRE WORKING PAPER SERIES NO. 2 (May 2011) TAGORE LOOKS EAST Sukanta Chaudhuri Sukanta Chaudhuri is an internationally renowned scholar of Renaissance English literature and of the writings of Rabindranath Tagore. He taught at Presidency College in Kolkata from 1973 to 1991 and at Jadavpur University from 1991 till his retirement in 2010. He is now Professor Emeritus at the latter institution. Chaudhuri works in the fields of European Renaissance studies, translation, and textual studies. His last major monograph is The Metaphysics of Text (Cambridge University Press, 2010). Chaudhuri has translated extensively from Rabindranath Tagore, Bankim Chandra Chattopadhyay, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Sukumar Ray, Rajshekhar Bose and other classical Bengali writers, and many modern Bengali poets. He is also General Editor of the Oxford Tagore Translations. Email: [email protected] The NSC Working Paper Series is published Citations of this electronic publication should be electronically by the Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre of the made in the following manner: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies in Singapore. Sukanta Chaudhuri, Tagore Looks East, Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Working Paper No 2 © Copyright is held by the author or authors of each (May 2011), http://nsc.iseas.edu.sg/documents/ Working Paper. working_papers/nscwps002.pdf NSC WPS Editors: NSC Working Papers cannot be republished, reprinted, or Geoff Wade Joyce Zaide reproduced in any format without the permission of the paper’s author or authors. Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Editorial Committee: Jayati Bhattacharya Geoff Wade Lucy Liu Joyce Zaide Tansen Sen The Nalanda-Sriwijaya Centre Working Paper Series has been established to provide an avenue for swift publication and wide dissemination of research conducted or presented within the Centre, and of studies engaging fields of enquiry of relevance to the Centre. -

Redescubriendo a Rabindranath Tagore –

i i ii ii REDESCUBRIENDO A TAGORE con el motivo del 150 aniversario del natalicio del vate indio Edición a cargo de Shyama Prasad Ganguly Indranil Chakravarty Esta es una publicación de Indo-Latin American Cultural Initiative, Mumbai en colaboración con Sahitya Akademi, Nueva Delhi y la Embajada de España en la India iii iii © de la edición: Indo-Latin American Cultural Initiative, 2011 © de las traducciones al castellano: ILACI © de los textos originales: los autores Primera edición, Septiembre de 2011 amaranta es la imprenta editorial de ILACI, dedicada a publicar la literatura india en castellano y la literatura española y latinoamericana en los idiomas de la india que incluye el inglés [email protected] Publicado por Indranil Chakravarty en nombre de ILACI, Green Meadows: 1C/501, Lokhandwala, Kandivali East, Mumbai: 400101, India ISBN: 978-81-921843-1-9 Diseño y maquetación: AnM Design Studio, Mumbai Imágenes: Según indicadas Quedan prohibidos, dentro de los límites establecidos en la ley y bajo los apercibimientos legalmente previstos, la reproducción total o parcial de esta obra por cualquier medio o procedimiento, ya sea electrónico o mecánico, el tratamiento informático, el alquiler o cualquier otra forma de cesión de la obra sin la autorización previa y por escrito de los titulares de los derechos. Impreso en Manjul Graphics, Mumbai iv iv a mi padre, Madhu Sudan Ganguly por ser ejemplo de sencillez e inspiración a mi hijo, Shagnik Chakravarty por darme fortaleza v v Índice Palabras Preliminares ix Indranil Chakravarty Introducción -

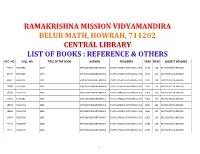

Ramakrishna Mission Vidyamandira Belur Math, Howrah, 711202 Central Library List of Books : Reference & Others Acc

RAMAKRISHNA MISSION VIDYAMANDIRA BELUR MATH, HOWRAH, 711202 CENTRAL LIBRARY LIST OF BOOKS : REFERENCE & OTHERS ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 44638 R032/ENC 1978 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1978 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44639 R032/ENC 1979 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1979 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 44641 R-032/BRI 1981 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1981 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15648 R-032/BRI 1982 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1982 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 15649 R-032/ENC 1983 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1983 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 17913 R032/ENC 1984 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1984 350 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18648 R-032/ENC 1985 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1985 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 18786 R-032/ENC 1986 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1986 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 19693 R-032/ENC 1987 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1987 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21140 R-032/ENC 1988 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1988 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21141 R-032/ENC 1989 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPEADIA BRITANNICA, INC 1989 100 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 1 ACC. NO. CALL. NO. TITLE OF THE BOOK AUTHOR PUBLISHER YEAR PRICE SUBJECT HEADING 21426 R-032/ENC 1990 ENYCOLPAEDIA BRITANNICA ENCYCLOPAEDIA BRITANNICA, ING 1990 150 ENCYCLOPEDIA-ENGLISH 21797 R-032/ENC 1991 ENYCOLPAEDIA -

Tagore's Gitanjali: a Critical Appraisal

ISSN 2319-5339 IISUniv.J.A. Vol.3(1), 12-20 (2014) Tagore’s Gitanjali: A Critical Appraisal Aju Mukhopadhyay Abstract The original book of poems in Bangla or Bengali titled Gitanjali or offering of songs was quite different from the Gitanjali (1912) in English comprising of 130 poems culled from ten books; all translated from the original Bangla to English by the poet himself which together with The Gardener (1913) won the Nobel Prize in 1913. Gitanjali was highly acclaimed throughout the world. William Rothenstein, who introduced the manuscript to the first gathering wrote, “Here was poetry of a new order which seemed to me on a level with that of the great mystics. Andrew Bradley, to whom I showed them agreed: ‘It looks as though we have at last a great poet among us again.’ “ Songs Unheard of The songs of Gitanjali were something unique in their approach; direct and pure, unheard of before with such lyrical richness though Rabindranath Tagore wrote Gitanjali, an offering of devotional songs in Bengali, which were somewhat in tune with the religious and devotional culture of the then Bengal. The richness of his songs took him beyond the traditions. Their trnslations in English vibrated with such romantic appeal to the English speaking world that at once it saw a link between Tagore and the Bible. They were overwhelmed to such an extent that they proposed a Nobel Prize for the creator. With the Nobel Prize the poet, first among the Asians to win it in literature, became suddenly so popular that he was enthused to reach the larger audience, almost under compulsion, and translation was almost the only way to reach them even in India, beyond Bengal. -

2018-Question Paper- STPGT-Music

This Booklet con tains 32 printed pages. AN18—XX Ques tion Book let No. &Òü šøÅ—šìy 32> ³å[‰t¡ šõË¡à "àìá¡ú šøÅ—-šå[ÑzA¡à Î}J¸à EXAMINATION—STPGT SUBJECT : MUSIC Do not open this Question Booklet until you are asked to do so. &Òü šøÅ—šy ™t¡Û¡o Jåºìt¡ >à ¤ºà Òì¤ t¡t¡Û¡o š™¢”z Jåºì¤> >à¡ú Read care fully all the instruc tions given at the back page and on the front page of this Ques tion Book let. &Òü šøÅ—šìy¹ ëÅÈ šõË¡à * šø=³ šõË¡àÚ ëƒ*Úà γÑz [>샢Åऺ㠳ì>àì™àK ÎÒA¡àì¹ šØl¡æ>¡ú In struc tions for Candidates š¹ãÛ¡à=¢ã샹 \>¸ [>샢Åऺã 1. OMR 1. Use Black Ballpoint Pen only for writing &Òü šøÅ—šìy ëºJ๠\>¸ &¤} l¡üv¡¹šìy l¡üv¡¹ particulars of this Question Booklet and [W¡[Òû¡t¡ A¡¹ìt¡ Ç¡‹å³ày A¡àìºà A¡à[º¹ ¤ºšìÚ–i¡ A¡º³ marking responses on the OMR ¤¸¤Ò๠A¡¹ç¡>¡ú Answer Sheet. 2. &Òü š¹ãÛ¡à¹ Î³Ú 2 Qsi¡à 30 [³[>i¡¡ú š¹ãÛ¡àÚ ë³ài¡ 2. This test is of 2 hours and 30 minutes 150 [i¡ MCQ ‹¹ì>¹ šøÅ— =àA¡ì¤¡ú šø[t¡ šøìÅ—¹ ³èº¸àS¡ 1 duration and consists of 150 MCQ-type Ò줡ú questions. Each question carries 1 mark. 3. ®å¡º l¡üv¡ì¹¹ \>¸ ëA¡àì>à ˜¡oàuA¡ >´¬¹ =àA¡ì¤ >à¡ú 3. There is no negative marking for any wrong answer. -

Nation and Imagination

CHAPTER 6 Nation and Imagination THIS CHAPTER moves out into three concentric circles. The innermost cir- cle tells the story of a certain literary debate in Bengal in the early part of the twentieth century. This was a debate about distinctions between prose, poetry, and the status of the real in either, and it centered on the writings of Rabindranath Tagore. Into these debatesÐand here is my second cir- cleÐI read a global history of the word ªimagination.º Benedict Ander- son's book Imagined Communities has made us all aware of how crucial the category ªimaginationº is to the analysis of nationalism.1 Yet, com- pared to the idea of community, imagination remains a curiously undis- cussed category in social science writings on nationalism. Anderson warns that the word should not be taken to mean ªfalse.º2 Beyond that, how- ever, its meaning is taken to be self-evident. One aim of this chapter is to open up the word for further interrogation and to make visible the heterogenous practices of seeing we often bring under the jurisdiction of this one European word, ªimagination.º My third and last move in the chapter is to build on this critique of the idea of imagination an argument regarding a nontotalizing conception of the political. To breathe heteroge- neity into the word ªimagination,º I suggest, is to allow for the possibility that the ®eld of the political is constitutively not singular. I begin, then, with the story of a literary debate. NATIONALISM AS WAYS OF SEEING It does not take much effort to see that a photographic realism or a dedi- cated naturalism could never answer all the needs of vision that modern nationalisms create. -

Quality Assessment of Copyright Free Tagoreana: a Study

Annals of Library and Information Studies Vol. 58, September 2011, pp. 257-269 Quality assessment of copyright free Tagoreana: a study Partha Pratim Ray Librarian, Institute of Education, Visva-Bharati, West Bengal-731 235, India, Email: [email protected] Rabindranath Tagore gave copyright of his intellectual output to Visva-Bharati. The extended period of copyright ended in December 2001. Private publishers have been free to publish the writings of Rabindranath Tagore since then. The paper attempts to study whether complete and accurate Bengali writings of Ranbindranath Tagore are being published by private publishers. It is observed from the study that a small number of Bengali publishers are publishing only commercially viable titles of Rabindranath Tagore. The prices of the books are lower but are of poor quality with number of mistakes that have been identified in the study. The quality of paper used is also poor. Introduction Visva-Bharati Granthan Vibhaga (VBGV) The first book of Rabindranath Tagore, Kavi-Kahini In the year 1923, Rabindranath Tagore established was published in the year 1878 by his friend Prabodh Visva-Bharati Granthan Vibhaga (VBGV), the Chandra Ghosh. Regarding this publication publishing department of the University and in the Rabindranath Tagore wrote, “When I was in same year he published the dance drama Basanta . Ahmedabad with my brother, my friend astonished But regular publication started from the year 1925 1 me by sending this book” . The second one Banaphul with the publication of Puravi. Before that the was published in the year 1880 by the poet’s elder publication right of Tagoreana was given to brother Somendranath. -

Translation of 'Seasons of Life: a Panoramic Selection of Songs by Rabindranath Tagore' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected]

University of Dayton eCommons Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Department of Electrical and Computer Publications Engineering 2014 Translation of 'Seasons of Life: A Panoramic Selection of Songs by Rabindranath Tagore' Monish Ranjan Chatterjee University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub Part of the Computer Engineering Commons, Electrical and Electronics Commons, Electromagnetics and Photonics Commons, Optics Commons, Other Electrical and Computer Engineering Commons, and the Systems and Communications Commons eCommons Citation Chatterjee, Monish Ranjan, "Translation of 'Seasons of Life: A Panoramic Selection of Songs by Rabindranath Tagore'" (2014). Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications. Paper 361. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/ece_fac_pub/361 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electrical and Computer Engineering Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Preface A project bordering on the impossible, one that was worked on sporadically over a very long time is at long last ready to awaken to its life in print. When I decided in the 1980s that Bengal's priceless literature ought to be given its rightful place in the world of letters in order for readers outside the Bengali language to have access to it, and that even a practitioner of engineering and science might summon the courage and commitment to offer his labors to it, I was most apprehensive about taking on what to me was the most sacred treasure in that domain - the lyrical songs of Rabindranath Tagore known to all beholden Bengalis collectively as Rabindra Sangeet.