Untitled, Undated Document, Rtskhldni, 533-6-317

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM

SPYCATCHER by PETER WRIGHT with Paul Greengrass WILLIAM HEINEMANN: AUSTRALIA First published in 1987 by HEINEMANN PUBLISHERS AUSTRALIA (A division of Octopus Publishing Group/Australia Pty Ltd) 85 Abinger Street, Richmond, Victoria, 3121. Copyright (c) 1987 by Peter Wright ISBN 0-85561-166-9 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. TO MY WIFE LOIS Prologue For years I had wondered what the last day would be like. In January 1976 after two decades in the top echelons of the British Security Service, MI5, it was time to rejoin the real world. I emerged for the final time from Euston Road tube station. The winter sun shone brightly as I made my way down Gower Street toward Trafalgar Square. Fifty yards on I turned into the unmarked entrance to an anonymous office block. Tucked between an art college and a hospital stood the unlikely headquarters of British Counterespionage. I showed my pass to the policeman standing discreetly in the reception alcove and took one of the specially programmed lifts which carry senior officers to the sixth-floor inner sanctum. I walked silently down the corridor to my room next to the Director-General's suite. The offices were quiet. Far below I could hear the rumble of tube trains carrying commuters to the West End. I unlocked my door. In front of me stood the essential tools of the intelligence officer’s trade - a desk, two telephones, one scrambled for outside calls, and to one side a large green metal safe with an oversized combination lock on the front. -

Rapport De Recherche #28 LES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT SOVIÉTIQUES ET RUSSES : CONSIDÉRATIONS HISTORIQUES

Centre Français de Recherche sur le Renseignement 1 LES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT SOVIÉTIQUES ET RUSSES : CONSIDÉRATIONS HISTORIQUES Colonel Igor PRELIN Rapport de recherche #28 Avril 2021 2 PRÉSENTATION DE L’AUTEUR Le colonel Igor Nicolaevich Prelin a servi toute sa carrière (1962-1991) au KGB où il a occupé successivement des fonctions au Service de contre-espionnage, au Service de renseignement (Guinée, Sénégal, Angola), à l’École de renseignement – en tant qu'instructeur il a eu Vladimir Poutine parmi ses élèves – et comme officier de presse du dernier président du KGB, le général Kriouchkov. De 1995 à 1998, le colonel Prelin est expert auprès du Comité de la Sécurité et de la Défense du Conseil de la Fédération de Russie (Moscou). Depuis, il consacre son temps à l’écriture d’essais, de romans et de scénarios, tout en poursuivant en parallèle une « carrière » d’escrimeur international. ABOUT THE AUTHOR Colonel Igor Nicolaevich Prelin served his entire career (1962-1991) in the KGB, where he successively held positions in the Counterintelligence Service, the Intelligence Service (Guinea, Senegal, Angola), the Intelligence School - as a professor he had Vladimir Putin among his students - and as press officer to the last KGB president, General Kriushkov. From 1995 to 1998, Colonel Prelin was an expert at the Committee on Security and Defense of the Council of the Russian Federation (Moscow). Since then, he has devoted his time to writing essays, novels and screenplays, while pursuing a "career" as an international fencer. RÉSUMÉ 3 LES SERVICES DE RENSEIGNEMENT SOVIÉTIQUES ET RUSSES : CONSIDÉRATIONS HISTORIQUES Les services de renseignement et de sécurité Il existe un certain nombre de traits caractéristiques soviétiques furent sans aucun doute les plus du renseignement soviétique à l’origine de son efficacité. -

AUGUST 4, 1972 More People Attend the Event

R . I, JE'/.' I t :! !! I ST.O~ ICAL ASS OC , 209 ANGE LL ST. 11 PROV . c,, R, I. 02906 Support Jewish Read By More Than Agencies 35,000 . With Your Membership People VOLUME LVI, NUMBER 23 PRIDAY,AUGUSf.f, 1972 12 PAGES lSc PER COPY U.S. Intelligence Sources Hoffman Says Everyone Premier Golda Meir Appeals In Florida Is Jewish Say Soviet U~ion Removing MJAMI BEACH - Abbh To Sadat For New Start '. loffman, one of the "Chlcap Seven" whose trial was c\JIIDected Most Of Its Warplanes with the 1968 Democratic Toward Peace In Mideast WASHINGTON - Unlt8d 1be prlnctpal disagreement Convention In Chicago, waa bac:t JERUSALEM Premier diplomacy In soft Janiuage, she States in.telllgence sources say between American and l:rraell for this one and waa staytng at Golda Meir appealed to President did not change the substance of there are "strong Indications" lnteWcence speclalt.sts seems to Plamln:.-o Park. Wben asked for Anwar el-Sadat of Egypt to Join In Israel's negodatlng terms on the that the Sovlet Union Is removing center- on whether Sovlet combat an lnterVtew; Hofhrun made It making a new start toward peace occasion of the Soviet withdrawal. from Egypt most of Its warp! anes units - what Mrs. Meir called Immediately clear that President 1n the Middle East, to "meet as Mrs. Meir warned that assigned with Sovlet fiylngcrewa "strategic forces" - are being Nixon wH his major opposition equals, and make a Joint supreme premature Judgments about a to the Egyptian air defenses. withdrawn. while George McGcnern wu "a effort to arrive at an agreed Sovlet "exodus from Egypt" These Intelligence sources American Intelligence mensch." "Ally Jew for Nixon la solution." would become a source of said It appeared that among the sources, while caudonlng that It • goy, even Golda Meir, Hoffman, In the Government's first disappointment. -

Editor's Note

Editor’s Note This issue begins with an article by David Patrick Houghton analyzing U.S. decision-making during the so-called Pueblo Crisis that erupted in January 1968 when North Korean forces seized the USS Pueblo, a naval intelligence vessel operating in international waters off North Korea’s coast. U.S. policymakers at the time mistakenly assumed that the Soviet Union had abetted the North Korean seizure, and thus the Downloaded from http://direct.mit.edu/jcws/article-pdf/17/4/1/698753/jcws_e_00594.pdf by guest on 29 September 2021 crisis took on a distinct Cold War dimension. Houghton seeks to understand why U.S. policymakers eschewed the use of military force to rescue the hostages and instead allowed the crisis to stretch out for nearly a year. In retrospect, many scholars and former officials have cited the U.S. military involvement in Vietnam (with more than 540,000 U.S. troops deployed there) as the main reason that President Lyndon B. Johnson did not want to embark on another armed conflict over the Pueblo,but Houghton shows that things were not so clear-cut at the time. He demonstrates that analogies with earlier hostage seizures and with recent shoot-downs of U.S. aircraft helped to shape the Johnson administration’s deliberations. Seeking to avoid the loss of any hostages while preserving national “honor,” U.S. officials gradually pieced together a face-saving compromise. The next article, by TommasoPiffer, discusses the relationship between the British and U.S. clandestine operations agencies that were active during World War II—the United Kingdom’s Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the U.S. -

Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence

Russia • Military / Security Historical Dictionaries of Intelligence and Counterintelligence, No. 5 PRINGLE At its peak, the KGB (Komitet Gosudarstvennoy Bezopasnosti) was the largest HISTORICAL secret police and espionage organization in the world. It became so influential DICTIONARY OF in Soviet politics that several of its directors moved on to become premiers of the Soviet Union. In fact, Russian president Vladimir V. Putin is a former head of the KGB. The GRU (Glavnoe Razvedvitelnoe Upravleniye) is the principal intelligence unit of the Russian armed forces, having been established in 1920 by Leon Trotsky during the Russian civil war. It was the first subordinate to the KGB, and although the KGB broke up with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991, the GRU remains intact, cohesive, highly efficient, and with far greater resources than its civilian counterparts. & The KGB and GRU are just two of the many Russian and Soviet intelli- gence agencies covered in Historical Dictionary of Russian and Soviet Intelligence. Through a list of acronyms and abbreviations, a chronology, an introductory HISTORICAL DICTIONARY OF essay, a bibliography, and hundreds of cross-referenced dictionary entries, a clear picture of this subject is presented. Entries also cover Russian and Soviet leaders, leading intelligence and security officers, the Lenin and Stalin purges, the gulag, and noted espionage cases. INTELLIGENCE Robert W. Pringle is a former foreign service officer and intelligence analyst RUSSIAN with a lifelong interest in Russian security. He has served as a diplomat and intelligence professional in Africa, the former Soviet Union, and Eastern Europe. For orders and information please contact the publisher && SOVIET Scarecrow Press, Inc. -

Lockenour on Perrault, 'The Red Orchestra'

H-German Lockenour on Perrault, 'The Red Orchestra' Review published on Tuesday, April 1, 1997 Gilles Perrault. The Red Orchestra. New York: Schocken Books, 1989. 494 pp. $12.95 (paper), ISBN 978-0-8052-0952-5. Reviewed by Jay B. Lockenour (Temple University) Published on H-German (April, 1997) "Soldiers of the 23rd Panzer Division, the Soviet Union salutes you. Your gay days in Paris are over now. Your comrades will already have warned you of what is happening here. Soon you will find out for yourselves." These words, blaring from loudspeakers just behind the Soviet lines, welcomed German troops to the Eastern Front. More damaging to German efforts, however, was the fact that the Soviet High Command seemed intimately acquainted with German offensive plans. During the German Operation Blue in 1942, Soviet armies always seemed to be in the right place, and when they retreated, it was always in the direction of OperationBlue 's objective, Stalingrad. The reasons for these successes may lie with the so-called Red Orchestra, the subject of the two books under review. ("Orchestra" is a common term for spy rings whose "pianists" [radio operators] play their "music" of coded messages.) The Red Orchestra, based in Paris and covering nearly all of German-occupied Europe, including Germany itself, was "conducted" by Leopold Trepper, a Polish Jew and the hero of both accounts, the first by Gilles Perrault and the second by V. E. Tarrant. Perrault's rendering is masterful, suspenseful, and reads like a thriller. Trepper and his associates were for years able to smuggle valuable information out of Germany. -

Mar AP 2018.Pub

The Voice of March/April 2018 Congregaon Kol Emeth Adar/Nissan/Iyar 5778 5130 W. Touhy Avenue Skokie, Illinois 60077 847-673-3370 www.KolEmethSkokie.org Message From The Rabbi In looking for Jewish heroes to return of Trepper and all the other spies to Moscow. speak about, I occasionally come But Trepper stayed put and continued his work. He upon a story so extraordinary that I even warned Stalin in 1941 of Germany’s plans to have to share it with a wider invade the Soviet Union, but to no avail. Stalin audience. Such is the story of willingly blinded himself to the obvious. Leopold Trepper. After June 22, 1941, when Operation Barbarossa, Born into a poor Jewish family in Poland, Trepper the German invasion of the Soviet Union took place, became a left -wing activist, organizing strikes and and Russia was now on the side of the Allies against suffering imprisonment for his efforts in this Germany, Trepper came into his own. The Germans direction. He joined the left -wing Zionist movement called his spy group Die Rote Kapelle, the Red Hashomer Hatzair, and emigrated to Palestine with Orchestra. This spy group, led by a Jew, in the heart like -minded comrades in 1924. Naturally, once he of Nazi -occupied Europe, sent information in such arrived, he organized a labor union Ichud —Unity — quantity and of such quality that the Germans but this was a union of both Jewish and Arab themselves said this work was worth 100,000 allied workers. He also joined the (illegal) Palestine troops. -

Joseph Berger: the Comintern’S and Münzenberg’S Expert on Middle Eastern Affairs

Joseph Berger: The Comintern’s and Münzenberg’s Expert on Middle Eastern Affairs von Mario Kessler Mario Kessler Joseph Berger: The Comintern’s and Münzenberg’s Expert on Middle Eastern Affairs1 Joseph Berger-Barzilai (original name Joseph Isaac Zilsnik, other form Zeliaznik), 1904– 1978, was founding member and secretary of the Communist Party of Palestine and who fell victim to Stalin’s purges.2 Berger-Barzilai was born in Cracow, Poland in 1904. In 1914, his family fled the Russian army which treathened to invade their city for Vienna, and moved in 1916 to Bielitz, Silesia. Young Joseph was brought up as an orthodox Jew and a Zionist, becoming active in the Zionist Wanderbund Blau-Weiß. He emigrated to Palestine at the age of 15 in 1919. There he worked first on road construction and then as a translator in an engenieering firm. During his life he spoke Yiddish, German, Polish, English, Hebrew, and Russian. Originally a member of the leftist Zionist organization Hashomer Hatzair, he became soon a communist, took part in the founding of one of the communist groups, the Communist Party of Palestine, in 1922, and became its secretary. It was then that he assumed the name Berger. Together with Wolf Averbukh, he was responsible for the unification of various left-wing groups that had broken with Zionism to the Palestiner Komunistishe Partey, the Palestine Communist Party, in 1923. The party had to operate under illegal conditions since the British Mandate Authority had outlawed all communist activities in May 1921. Berger became deputy secretary of the party that joined the Comintern in March 1924.3 For this mission, he was sent to Moscow. -

Spartacist No. 41-42 Winter 1987-88

· , NUMBER 41-42 ENGLISH EDITION WINTER 1987-88 .ONE DOLLAR/75 PENCE ," \0, 70th Anniversary of Russian Revolution Return to the Road of Lenin and, Trotskyl PAGE 4 e___ __ _. ...,... • :~ Where Is Gorbachev's Russia Going? PAGE 20 TheP.oland,of LU)(,emburgvs.th'e PolalJdof Pilsudski ;... ~ ;- Me.moirs ofaRevoluti0l.1ary Je·wtsl1 Worker A Review .., .. PAGE 53 2 ---"---Ta bI e of Contents -'---"..........' ..::.....-- International Class-Struggle Defense , '. Soviet Play Explodes Stalin's Mo!?cow Trials Free Mordechai Vanunu! .................... 3 'Spectre of, Trotsky Hau'nts '- " , Gorbachev's' Russia ..... : .... : ........ : ..... 35 70th Anniversary of Russian Revolution Reprinted from Workers ,vanguard No, 430, Return'to the Road of 12 June 1987 ' lenin and Trotsky! ..... , ..................... 4 Leni~'s Testament, •.....• : ••••.•.. : ~ •••....•• : .1 •• 37' , Adapted from Workers Vanguard No, 440, The Last Wo~ds of, Adolf Joffe ................... 40 , 13 November 1987' 'j' .•. : Stalinist Reformers Look to the Right Opposition:, ' Advertisement: The Campaign to \ Bound Volumes of the Russian "Rehabilitate" Bukharin ...•.... ~ .... '..... ;. 41 , Bulletin of the'OpP-osition, 1929-1941 .... 19 , Excerpted from Workers Vanguard No. 220, 1 December 1978, with introduction by Spartacist 06'bRBneHMe: nonHoe M3AaHMe pyccKoro «EilOnneTeHR In Defense of Marshal Tukhachevsky ...,..45 , Onn03M4MM» 1929-1941 ................ .' .... ,". 19 Letter and reply reprinted from Workers Vanguard No'. 321, 14 January 1983' Where Is Gorbachev's Russia -

The National Library of Australia Magazine

THE NATIONAL LIBRARY DECEMBEROF AUSTRALIA 2014 MAGAZINE KEEPSAKES PETROV POEMS GOULD’S LOST ANIMALS WILD MAN OF BOTANY BAY DEMISE OF THE EMDEN AND MUCH MORE … keepsakes australians and the great war 26 November 2014–19 July 2015 National Library of Australia Free Exhibition Gallery Open Daily 9 am–5 pm nla.gov.au #NLAkeepsakes James C. Cruden, Wedding portrait of Kate McLeod and George Searle of Coogee, Sydney, 1915, nla.pic-vn6540284 VOLUME 6 NUMBER 4 DECEMBER 2014 TheNationalLibraryofAustraliamagazine The aim of the quarterly The National Library of Australia Magazine is to inform the Australian community about the National Library of Australia’s collections and services, and its role as the information resource for the nation. Copies are distributed through the Australian library network to state, public and community libraries and most libraries within tertiary-education institutions. Copies are also made available to the Library’s international associates, and state and federal government departments and parliamentarians. Additional CONTENTS copies of the magazine may be obtained by libraries, public institutions and educational authorities. Individuals may receive copies by mail by becoming a member of the Friends of the National Library of Australia. National Library of Australia Parkes Place Keepsakes: Australians Canberra ACT 2600 02 6262 1111 and the Great War nla.gov.au Guy Hansen introduces some of the mementos NATIONAL LIBRARY OF AUSTRALIA COUNCIL of war—personal, political and poignant—featured Chair: Mr Ryan Stokes Deputy -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS WINTER 2021 ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR Editorial

169 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS BAR VICTORIAN ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 Sexual The Annual Bar VICTORIAN Harassment: Dinner is back! It’s still happening BAR By Rachel Doyle SC NEWS WINTER 2021 169 Plus: Vale Peter Heerey AM QC, founder of Bar News ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR editorial NEWS 50 Evidence law and the mess we Editorial are in GEOFFREY GIBSON Not wasting a moment 5 54 Amending the national anthem of our freedoms —from words of exclusion THE EDITORS to inclusion: An interview with Letters to the Editors 7 the Hon Peter Vickery QC President’s message 10 ARNOLD DIX We are Australia’s only specialist broker CHRISTOPHER BLANDEN 60 2021 National Conference Finance tailored RE-EMERGE 2021 for lawyers. With access to all major lenders Around Town and private banks, we’ll secure the best The 2021 Victorian Bar Dinner 12 Introspectives JUSTIN WHEELAHAN for legal professionals home loan tailored for you. 12 62 Choices ASHLEY HALPHEN Surviving the pandemic— 16 64 Learning to Fail JOHN HEARD Lorne hosts the Criminal Bar CAMPBELL THOMSON 68 International arbitration during Covid-19 MATTHEW HARVEY 2021 Victorian Bar Pro 18 Bono Awards Ceremony 70 My close encounters with Nobel CHRISTOPHER LUM AND Prize winners GRAHAM ROBERTSON CHARLIE MORSHEAD 72 An encounter with an elected judge Moving Pictures: Shaun Gladwell’s 20 in the Deep South portrait of Allan Myers AC QC ROBERT LARKINS SIOBHAN RYAN Bar Lore Ful Page Ad Readers’ Digest 23 TEMPLE SAVILLE, HADI MAZLOUM 74 No Greater Love: James Gilbert AND VERONICA HOLT Mann – Bar Roll 333 34 BY JOSEPH SANTAMARIA -

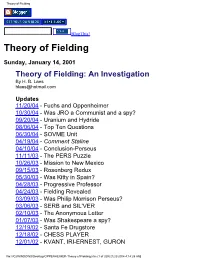

Theory of Fielding

Theory of Fielding BlogThis! Theory of Fielding Sunday, January 14, 2001 Theory of Fielding: An Investigation By H. B. Laes [email protected] Updates 11/20/04 - Fuchs and Oppenheimer 10/30/04 - Was JRO a Communist and a spy? 09/20/04 - Uranium and Hydride 08/06/04 - Top Ten Questions 06/30/04 - SOVME Unit 04/19/04 - Comment Staline 04/10/04 - Conclusion-Perseus 11/11/03 - The PERS Puzzle 10/26/03 - Mission to New Mexico 09/15/03 - Rosenberg Redux 05/30/03 - Was Kitty in Spain? 04/28/03 - Progressive Professor 04/24/03 - Fielding Revealed 03/09/03 - Was Philip Morrison Perseus? 03/06/03 - SERB and SIL'VER 02/10/03 - The Anonymous Letter 01/07/03 - Was Shakespeare a spy? 12/19/02 - Santa Fe Drugstore 12/18/02 - CHESS PLAYER 12/01/02 - KVANT, IRI-ERNEST, GURON file:///C|/WINDOWS/Desktop/OPPENHEIMER-Theory of Fielding.htm (1 of 329) [12/2/2004 4:14:25 AM] Theory of Fielding 11/10/02 - Goldsmith 09/17/02 - The Mironov-Zarubin Affair 09/01/02 - Sacred Secrets 12/19/01 - MAR and "D" 12/01/01 - Feklisov 08/26/01 - Gold Testimony 07/05/01 - Japan 05/25/01 - Mitrokhin Contents Introduction Set A - Comment Staline Set B - Spanish Civil War Set C - FOGEL'-PERS Set D - Drugstore Safehouse Set E - The Eltenton-Chevalier Incident Set F - Prodigy, Prankster, Scientist, Spy Set G - VEKSEL, KVANT, IRI-ERNEST, GURON Set H - Hero of Russia Set I - RELE-SERB Set J - September, 1941 Set K - MLAD's Report Set L - Mission to New Mexico Set M - MAR and "D" Set N - Post Los Alamos, 1945 Set O - A Freeze in 1946 Set P - Shelter Island and Paris, 1947 Set Q - 1948,