Influences of Surface Processes on Fold Growth During 3D Detachment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Poster Final

Evidence for polyphase deformation in the mylonitic zones bounding the Chester and Athens Domes, in southeastern Vermont, from 40Ar/39Ar geochronology Schnalzer, K., Webb, L., McCarthy, K., University of Vermont Department of Geology, Burlington Vermont, USA CLM 40 39 Sample Mineral Assemblage Metamorphic Facies Abstract Microstructure and Ar/ Ar Geochronology 18CD08A Quartz, Muscovite, Biotite, Feldspar, Epidote Upper Greenschist to Lower Amphibolite The Chester and Athens Domes are a composite mantled gneiss QC Twelve samples were collected during the fall of 2018 from the shear zones bounding the Chester and Athens Domes for 18CD08B Quartz, Biotite, Feldspar, Amphibole Amphibolite Facies 18CD08C Quartz, Muscovite, Biotite, Feldspar, Epidote Upper Greenschist to Lower Amphibolite dome in southeast Vermont. While debate persists regarding Me 40 39 microstructural analysis and Ar/ Ar age dating. These samples were divided between two transects, one in the northeastern 18CD08D Quartz, Muscovite, Biotite, Feldspar, Garnet Upper Greenschist to Lower Amphibolite the mechanisms of dome formation, most workers consider the VT NH section of the Chester dome and the second in the southern section of the Athens dome. These samples were analyzed by X-ray 18CD08E Quartz, Muscovite Greenschist Facies domes to have formed during the Acadian Orogeny. This study diraction in the fall of 2018. Oriented, orthogonal thin sections were also prepared for each of the twelve samples. The thin sec- 18CD09A Quartz, Amphibole Amphib olite Facies 40 CVGT integrates the results of Ar/Ar step-heating of single mineral NY tions named with an “X” were cut parallel to the stretching lineation (X) and normal to the foliation (Z) whereas the thin sections 18CD09B Quartz, Biotite, Feldspar, Amphibole, Muscovite Amphibolite Facies grains, or small multigrain aliquots, with data from microstruc- 18CD09C Quartz, Amphibole, Feldspar Amphibolite Facies named with a “Y” have been cut perpendicular to the ‘X-Z’ thin section. -

Sedimentary Record of Cretaceous And

SEDIMENT AR Y RECORD OF CRETACEOUS AND TER TIAR Y SALT MOVEMENT, EAST TEXAS BASIN: TIMES, RATES, AND LUMES OF SALT FLOW, IMPLICATIONS TO NUCLEAR-WA TE ISOLATION AND PETROLEUM EXPLO ATION by Steven J. Seni and M. P. A. ackson This work was supported by U.S. Depart ent of Energy and funded under Contract No. DE-AC 7-80ET46617 CONTENTS ABSTRACT . • 00 INTRODUCTION. • 00 Data Base. • 00 Early History of Basin Formation and Infilling • 00 Geometry of Salt Structures • 00 EVOLUTIONARY STAGES OF DOME GROWTH. • 00 Pillow Stage . • 00 Geometry of Overlying Strata . • 00 Geometry of Surrounding Strata • 00 Depositional Facies and Lithostratigraph • 00 Diapir Stage • • 00 Geometry of Surrounding Strata • 00 Depositional Facies and Lithostratigraph • 00 Post-Diapir Stage • 00 Geometry of Surrounding Strata • 00 Depositional Facies and Lithostratigraphy • 00 Holocene Analogues. • 00 Discussion • 00 Significance to Subtle Petroleum Traps • 00 PATTERNS OF SALT MOVEMENT IN TIME AND SPAC • 00 Group 1: Pre-Glen Rose Subgroup (pre-112 Ma) - Periphery of Diapir Province • • 00 Group 2: Glen Rose Subgroup to Washita Group 112 to 98 Ma)- Basin Axis • 00 Group 3: Post-Austin Group (86 to 56 Ma) -- Per phery of Diapir Province • • 00 Initiation and Acceleration of Salt Flow • • 00 Overview of Dome History • • 00 RATES OF SALT MOVEMENT AND DOME GROWTH • • 00 Assumptions • • 00 Proven Propositions. • 00 Unproven Propositions • 00 Incorrect Propositions • • 00 Distinguishing Between Syndepositional and Post-D positional Thickness Variations. • 00 The Problem • • 00 Structural Evidence • • 00 Sedimentological Evidence • • 00 Methodology • • 00 Distinguishing Between Regional and Salt-Re ated Thickness Variations. • 00 Volume of Salt Mobilized and Estimates of S t Loss • 00 Rates of Dome Growth • • 00 Net Rates of Pillow Growth • 00 Net Rates of Diapir Growth • 00 Gross Rates of Diapir Growth • • 00 Growth Rates and Strain Rates • 00 IMPLICA TIONS TO WASTE ISOLATION • • 00 CONCLUSIONS • • 00 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS • • 00 REFERENCES • 00 APPENDICES • 00 Figures 1. -

Map Showing Geology, Structure, and Geophysics of the Central Black

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Prepared in cooperation with the SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATIONS MAP 2777 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOUTH DAKOTA SCHOOL OF MINES AND TECHNOLOGY FOUNDATION SHEET 2 OF 2 Pamphlet accompanies map 104°00' 103°30' 103°00' 104°00' 103°30' 103°00' ° ° EXPLANATION FOR MAPS F TO H 44 30' 44°30' EXPLANATION 44 30' 44°30' EXPLANATION Spearfish Geologic features 53 54 Tertiary igneous rocks (Tertiary and post-Tertiary Spearfish PHANEROZOIC ROCKS 90 1 90 sedimentary rocks not shown) Pringle fault 59 Tertiary igneous rocks (Tertiary and post-Tertiary Pre-Tertiary and Cretaceous (post-Inyan Kara sedimentary rocks not shown) Monocline—BHM, Black Hills monocline; FPM, Fanny Peak monocline 52 85 Group) rocks 85 Sturgis Sturgis Pre-Tertiary and Cretaceous (post-Inyan Kara A Proposed western limit of Early Proterozoic rocks in subsurface 55 Lower Cretaceous (Inyan Kara Group), Jurassic, Group) rocks 57 58 60 14 and Triassic rocks 14 Lower Cretaceous (Inyan Kara Group), Jurassic, B Northern extension (fault?) of Fanny Peak monocline and Triassic rocks Paleozoic rocks C Possible eastern limit of Early Proterozoic rocks in subsurface 50 Paleozoic rocks Precambrian rocks S Possible suture in subsurface separating different tectonic terranes 89 51 89 2 PRECAMBRIAN ROCKS of Sims (1995) 49 Contact St 3 G Harney Peak Granite (unit Xh) Geographic features—BL, Bear Lodge Mountains; BM, Bear Mountain; Fault—Dashed where approximately located G DT DT, Devils Tower 48 B Early Proterozoic rocks, undivided Anticline—Showing trace of axial surface and 1 St Towns and cities—B, Belle Fourche; C, Custer; E, Edgemont; HS, Hot direction of plunge. -

TIES, MONTANA. by CF BOWEN. Previo

ANTICLINES IN A PART OF THE MUSSELSHELL VALLEY, MUSSELSHELL, MEAGHER, AND SWEETGRASS COUN TIES, MONTANA. By C. F. BOWEN. INTRODUCTION. Previous investigations had shown that the Musselshell Valley, Mont, is an area in which the rocks have undergone considerable folding. On the basis of this information work was begun in June, 1916, to determine the nature and extent of the folds and to make examination as to the possible occurrence of accumulations of oil and gas in them. The work has demonstrated the existence within the area studied of several well-developed anticlines and domes, which seem to offer structurally favorable places for the accumulation of oil and gas. The demonstration of the presence or absence of commercial accumulations of these fluids in the folds has been less conclusive, owing largely to the undeveloped condition of the area. No direct surface indications of oil were observed, but hydrogen sulphide gas escapes from several water seeps in one part of the area. It is also reported that gas was encountered in several wells dug for water. None of these reports could be verified. At the time of the examination drilling operations within the area were confined to two wells. One of these wells, on the Big Elk dome, had reached the Kootenai formation; the other, in the Woman's Pocket anticline, was probably somewhat more than halfway through the Colorado shale. In neither place had oil been discovered. Two other wells, one about 15 miles east of the area and the other about 12 miles south of the central portion of it, had previously been drilled through the Colo rado shale without any discovery of oil. -

The Green Mountain Anticlinorium in the Vicinity of Wilmington and Woodford Vermont

THE GREEN MOUNTAIN ANTICLINORIUM IN THE VICINITY OF WILMINGTON AND WOODFORD VERMONT By JAMES WILLIAM SKEHAN, S. J. VERMONT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. DOLL, Stale Geologist Published by VERMONT DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT MONTPELIER, VERMONT BULLETIN NO. 17 1961 = 0 0. Looking northwest from centra' \Vhitingham, from a point near C in WHITINCHAM IPlate 1 Looking across Sadawga Pond Dome to Haystack Mountain-Searsburg Ridge in the background; Stratton and Glastenburv Mountains in the far distance. Davidson Cemetery in center foreground on Route 8 serves as point of reference. TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE ABSTRACT 9 INTRODUCTION . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10 Location ........................ 10 Regional Geologic Setting . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13 Previous Geologic Work ................. 15 The Problem ...................... 16 Present Investigation ................... 18 Acknowledgments .................... 19 Topography . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19 Rock Exposure ..................... 20 Culture and Accessibility ................. 20 STRATIGRAPHY AND LITHOLOGY ............... 23 General Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23 Stratigraphic Nomenclature . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25 Lithologic Nomenclature ................. 26 Pre-Cambrian Rocks . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 General Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 27 Mount Holly Complex ................. 28 Stamford -

Feasibility of Constructing Large Underground Cavities: Volume II

FEASIBILITY OF CONSTRUCTING LARGE UNDERGROUND CAVITIES THE STABILITY OF DEEP LARGE-SPAN UNDERGROUND OPENINGS TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 3-648 Volume II June 1964 Sponsored by Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA Order No. 260-62 Amendment No. I U. S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station CORPS OF ENGINEERS Vicksburg, Mississippi FEASIBILITY OF CONSTRUCTING LARGE UNDERGROUND CAVITIES THE STABILITY OF DEEP LARGE-SPAN UNDERGROUND OPENINGS TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 3-648 Volume II June 1964 Sponsored by Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA Order No. 260-62 Amendment No. I U. S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station CORPS OFENGINEERS Vicksburg, Mississippi ARMY-MRC VICKSBURG, MISS." COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES RESEARCH FOUNDATION, INC. Golden, Colorado THE STABILITY OF DEEP LARGE SPAN UNDERGROUND OPENINGS Prepared for U. S. Army Engineer Waterways Experiment Station Corps of Engineers Vicksburg, Mississippi Contract No. DA-22-079-eng-334 Approved: CoaU 0,. Free! JaVid Cardard, Jr. / Director of Research Mathematician William H. Jurney Project Mathematician Thomas I. Sharps Geologist Project No. 320327 COLORADO SCHOOL OF MINES RESEARCH FOUNDATION TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Part I. Theoretical Considerations 1 The Spherical Cavity 1 The Elastic Case ...... 1 Introduction . 1 Derivation of Solutions for a Spherical Cavity in Uniform Stress Fields 2 Stresses and Displacements Due to Force Operative at a Point 3 Potential Stresses ...... 9 Field Stresses 11 Notes on Derivation of Solutions B and C . 14 The Plastic Case 20 The Prolate Spheroidal Cavity. ... .38 The Elastic Case 38 Introduction 38 Statement of the Problem 38 Three-Function Approach in Elasticity. ... 39 The Oblate Spheroidal Cavity . 51 The Elastic Case 51 Introduction ^ 51 Openings in Layered Media . -

GY 111 Lecture Notes Folds

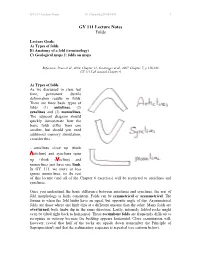

GY 111 Lecture Notes D. Haywick (2008-097) 1 GY 111 Lecture Notes Folds Lecture Goals: A) Types of folds B) Anatomy of a fold (terminology) C) Geological maps 2: folds on maps Reference: Press et al., 2004, Chapter 11; Grotzinger et al., 2007, Chapter 7; p 158-160 GY 111 Lab manual Chapter 6 A) Types of folds As we discussed in class last time, permanent ductile deformation results in folds. There are three basic types of folds (1) anticlines, (2) synclines and (3) monoclines. The adjacent diagram should quickly demonstrate how the basic folds differ from one another, but should you need additional memory stimulation, consider this… …anticlines close up (think vnticline) and synclines open up (think swncline) and monoclines just have one limb. In GY 111, we more or less ignore monoclines, so the rest of this lecture (and all of the Chapter 6 exercises) will be restricted to anticlines and synclines. Once you understand the basic difference between anticlines and synclines, the rest of fold morphology is fairly consistent. Folds can be symmetrical or asymmetrical. The former is when the fold limbs have an equal, but opposite angle of dip. Asymmetrical folds are those where one limb dips at a different amount than the other. Many folds are overturned; both limbs dip in the same direction. Lastly, intensely folded rocks might even be tilted right back to horizontal. These recumbent folds are frequently difficult to recognize in outcrop because the bedding appears horizontal. Close examination will, however, reveal that half of the rocks are upside down (remember the Principle of Superposition!) and that the sedimentary sequence is repeated (see cartoon below). -

W. John Nelson

TUR R W. John Nelson Department of Natural Resources ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY BULLETIN 100 1995 BULLETIN 100 1995 ILLINOIS STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY illiam W. Shilts, Chief Natural Resources Building 615 East Peabody Drive Champaign, Illinois 61820-6964 Cover Photo Steeply tilted lower Pennsylvanian sandstone on the southeast side of the L,usk Creek Fault Zone near Manson Ford, about 5 miles northeast of Dixon Springs, Pope County. Photo by W. John Nelson. Graphic Artist - Sandra Stecyk Plates - Michael Knapp Printed by authority of the State of Illinois/l995/3000 @ printed with soybean ink on recycled paper Acknowledgments STRUCTURAL FEATURES IN ILLINOIS Abstract Introduction Guidelines for Naming Structures Removal of Names New Names Major Structural Features Basins, Arches, and Domes Folds and Faults Northern Illinois Western Illinois Eastern Illinois Southern Illinois Structural History Precambrian Cambrian Period Ordovician Period Silurian Period Devonian Period Mississippian Period Pennsylvanian Period Late Paleozoic (?) Compressional Events Mesozoic (?) Extensional Events Cretaceous to Recent Events STRUCTURAL FEATURES - CATALOG BIBLIOGRAPHY TABLES 1 Wells that reach Precambrian rocks in Illinois 2 167 structures recommended for removal from stratigraphic records 3 33 renamed structures shown as follows: (new name) 4 33 newly named structural features shown as follows: (new) 5 In situ stress measurements in Illinois 6 Silurian reefs in Illinois FIGURES 1 Regional structural setting of Illinois 2 Major structural features in Illinois and neighboring states 3 Oil fields and structure of the Beech Creek ("Barlow") Limestone in part of Clinton County 4 Wells that reach Precambrian rocks in Illinois 5 Generalized Precambrian geology of eastern and central United States 6 An interpretive cross section of Rough Creek Graben 7 Stratigraphiccolumn showing the units mentioned in the text 8 Paleogeography of Illinois during deposition of Mt. -

Introduction to Structural Geology

Introduction to Structural Geology Patrice F. Rey CHAPTER 1 Introduction The Place of Structural Geology in Sciences Science is the search for knowledge about the Universe, its origin, its evolution, and how it works. Geology, one of the core science disciplines with physics, chemistry, and biology, is the search for knowledge about the Earth, how it formed, evolved, and how it works. Geology is often presented in the broader context of Geosciences; a grouping of disciplines specifically looking for knowledge about the interaction between Earth processes, Environment and Societies. Structural Geology, Tectonics and Geodynamics form a coherent and interdependent ensemble of sub-disciplines, the aim of which is the search for knowledge about how minerals, rocks and rock formations, and Earth systems (i.e., crust, lithosphere, asthenosphere ...) deform and via which processes. 1 Structural Geology In Geosciences. Structural Geology aims to characterise deformation structures (geometry), to character- ize flow paths followed by particles during deformation (kinematics), and to infer the direction and magnitude of the forces involved in driving deformation (dynamics). A field-based discipline, structural geology operates at scales ranging from 100 microns to 100 meters (i.e. grain to outcrop). Tectonics aims at unraveling the geological context in which deformation occurs. It involves the integration of structural geology data in maps, cross-sections and 3D block diagrams, as well as data from other Geoscience disciplines including sedimen- tology, petrology, geochronology, geochemistry and geophysics. Tectonics operates at scales ranging from 100 m to 1000 km, and focusses on processes such as continental rifting and basins formation, subduction, collisional processes and mountain building processes etc. -

Volcanoes in the Rio Grande Rift

Lite Volcanoes of the Rio Grande Rift spring 2013 issue 33 Ute Mountain is a volcano located nine miles southwest of Costilla, New Mexico that rises about 2,500 feet above the Taos Plateau. It is a lava dome composed of a volcanic rock called dacite, about 2.7 million years old. Photo courtesy of Paul Bauer. In This Issue... Volcanoes of the Rio Grande Rift • Volcano or Not a Volcano? Earth Briefs: Volcanic Hazards Volcanoes Crossword Puzzle • New Mexico’s Most Wanted Minerals—Spinel New Mexico’s Enchanting Geology Classroom Activity: Building a Flour Box Caldera Model, New Mexico Style! Through the Hand Lens • Short Items of Interest NEW MEXICO BUREAU OF GEOLOGY & MINERAL RESOURCES A DIVISION OF NEW MEXICO TECH http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publications/periodicals/litegeology/current.html VOLCANOES OF THE RIO GRANDE RIFT Maureen Wilks and Douglas Bland This is the third in a series of issues of Lite Geology related to Stratovolcano the most dominant landscape feature in New Mexico, the Rio Grande valley, and will explore the spectacular volcanoes A stratovolcano (or composite) is an upward steepening, scattered along the rift from the Colorado border to Mexico. sharp peaked mountain with a profile that most people Previous issues focused on the geologic evolution of the Rio identify as the classic volcanic shape, like Mt. Fuji in Japan. Grande rift (Spring 2012) http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/publictions/ No true stratovolcanoes are seen along the Rio Grande rift, but periodicals/litegeology/31/lite_geo_31spring12.pdf and the Mt. Taylor near Grants is a composite volcano and consists of history of the Rio Grande (Fall 2012) http://geoinfo.nmt.edu/ alternating layers of lava and ash. -

Extension Systems

69 EXTENSION SYSTEMS Extension systems are zones where plates split into two or more smaller blocks that move apart. To accommodate the separation, dominantly normal faults and even open fissures lead to stretching, rupture and lengthening of crustal rocks. At the same time, the lithosphere is thinned and the asthenosphere is upwelling below the necked lithosphere. Decompression during upwelling of the mantle results in partial melting. The produced basaltic magma is injected into the fissures or extruded as fissure eruptions along and on either side of the splitting linear region (graben and rifts). This mechanism, coeval lithospheric stretching and accretion of buoyant magma, is called rifting. It is called seafloor spreading once a rifted region becomes a plate boundary that creates new oceanic lithosphere as plates diverge from one another. The spreading centres shape elevated morphological forms, the mid-oceanic ridges, because magma and young, thin oceanic lithosphere are buoyant. Divergent plate boundaries are some of the most active volcanic zones on the Earth. Seafloor spreading is so important that it has created more than half of the Earth’s surface during the past 200 Ma. Since the new continents drift away from the locus of extension, they escape further deformation and marine sedimentation seals relict structures of the early rift on either side of the new ocean. These two sides are passive continental margins. The dominant stress field is extension. Bulk lithospheric rheologies control the development of large- scale extensional -

Geological Maps 2: Folded Strata

Geological Maps 2: Folded Strata The same factors responsible for metamorphism (chiefly pressure and temperature) are also responsible for rock deformation; however, the actual processes of deformation are complex which necessitates additional discussion here. If you take a volume of strata and place it deep inside the Earth, those rocks will experience pressure related to the mass of the overlying rocks. Geologists refer to this as the confining pressure. Confining pressure is generally isostatic (i.e., it is more or less uniform in all directions) and in general, the deeper you go, the higher it becomes. Since the strata are equally squeezed from all sides, the result is a net decrease in volume, but there is no change in shape of the rock volume (Figure 1). Not all pressure in the interior of the Earth is isostatic. Along a convergent plate boundary, for example, the pressure is directed between the two colliding plates. Pressure that is non-isostatic or directed is regarded as stress. There are three main types of stress that can affect rocks. Compressive stress (or compression) occurs when rocks are squeezed together such as along convergent plate boundaries and subduction zones (Figure 1b). Tensional shear (or tension) occurs when rocks are pulled apart (Figure 1c). This is the major force operating along divergent plate boundaries such as 0 Geological Maps 2: Folds 1 Figure 1: Effects of pressure on the volume and shape of rock strata. the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. The third type of stress, shear, occurs when rocks slide past one another (Figure 1d). This occurs along transform fault boundaries such as the San Andreas Fault in California or the Alpine Fault in New Zealand.