Reunion: a Portrait of Jim Lauderdale at Exit/In on the Venue's 43Rd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

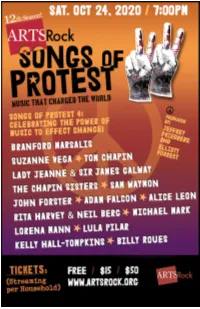

Songs-Of-Protest-2020.Pdf

Elliott Forrest Dara Falco Executive & Artistic Director Managing Director Board of Trustees Stephen Iger, President Melanie Rock, Vice President Joe Morley, Secretary Tim Domini, Treasurer Karen Ayres Rod Greenwood Simon Basner Patrick Heaphy David Brogno James Sarna Hal Coon Lisa Waterworth Jeffrey Doctorow Matthew Watson SUPPORT THE ARTS Donations accepted throughout the show online at ArtsRock.org The mission of ArtsRock is to provide increased access to professional arts and multi-cultural programs for an underserved, diverse audience in and around Rockland County. ArtsRock.org ArtsRock is a 501 (C)(3) Not For-Profit Corporation Dear Friends both Near and Far, Welcome to SONGS OF PROTEST 4, from ArtsRock.org, a non- profit, non-partisan arts organization based in Nyack, NY. We are so glad you have joined us to celebrate the power of music to make social change. Each of the first three SONGS OF PROTEST events, starting in April of 2017, was presented to sold-out audiences in our Rockland, NY community. This latest concert, was supposed to have taken place in-person on April 6th, 2020. We had the performer lineup and songs already chosen when we had to halt the entire season due to the pandemic. As in SONGS OF PROTEST 1, 2 & 3, we had planned to present an evening filled with amazing performers and powerful songs that have had a historical impact on social justice. When we decided to resume the series virtually, we rethought the concept. With so much going on in our country and the world, we offered the performers the opportunity to write or present an original work about an issue from our current state of affairs. -

Soundbyte September 2014

September 30, 2014 Vol 1 | Issue 6 In This Issue Legendary Artists Show Support for Turtles Victory 1 On the Hill & In the Know 2 In the Valley Below is On The Rise 3 SoundExchange Sponsors Americana Music Festival 2014 5 SoundExchange Rockin @ Lockn’ — 2014 Lockn’ Music Festival Recap 5 SoundExchange Collects Royalties from Around the World 6 Events 7 Legendary Artists Show Support for Turtles Victory In September, the 1960s band The Turtles won a critical legal victory in their lawsuit against Sirius XM. The Turtles sued because Sirius XM has taken the position that it doesn’t need permission — and therefore doesn’t need to pay for use of — pre-1972 recordings protected under state law, even though it does pay for post-1972 recordings that are protected by federal law. This relates to an issue that SoundExchange has long been fighting — the failure of some large digital radio services to pay for the use of such vintage recordings. We think Sirius XM’s position is wrong as a matter of law, and definitely wrong as a matter of justice! The California federal court agreed with our view of the law and sided with The Turtles in their lawsuit. As SoundExchange President and CEO Michael Huppe said in a statement, we believe that “all sound recordings have value, and ALL artists deserve to be paid fairly for the use of their music.” 1 www.soundexchange.com Now, legendary artists like Martha Reeves, T Bone Burnett, Mark Farner (Grand Funk Railroad), and Richie Furay (Buffalo Springfield) are sharing in this sentiment and praising The Turtles for taking up this cause. -

Countrybreakout Chart Covering Secondary Radio Since 2002

COUNTRYBREAKOUT CHART COVERING SECONDARY RADIO SINCE 2002 Thursday, July 26, 2018 NEWS CHART ACTION Cole Swindell, Dustin Lynch, Lauren Alaina New On The Chart —Debuting This Week song/artist/label—Chart Position Announce Fall Reason To Drink Tour Turnin' Me On/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 61 Night Shift/Jon Pardi/Capitol — 75 Wildest Dreams/Richard Schroder/Ampliier Records — 79 Ain't No App For That/Tony Jackson/DDS Entertainment — 80 Greatest Spin Increase song/artist/label—Spin Increase Desperate Man/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 497 She Got The Best Of Me/Luke Combs/Columbia — 258 Burning Man/Dierks Bentley feat. Brothers Osbourne/Capital — 248 Turnin' Me On/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 246 All Day Long/Garth Brooks/Pearl Records Inc — 209 Blue Tacoma/Russell Dickerson/Triple Tigers — 198 Lose It/Kane Brown/RCA Nashville — 158 Night Shift/Jon Pardi/Capitol — 151 Most Added song/artist/label—No. of Adds Cole Swindell, Dustin Lynch, and Lauren Alaina will head out on the Desperate Man/Eric Church/EMI Records Nashville — 21 road on the Reason To Drink…Another Tour on Oct. 4. The tour will hit 25 Turnin' Me On/Blake Shelton/Warner Bros. — 20 cities through December including Richmond, Phoenix, Minneapolis, New American Girls/CJ Solar/Sea Gayle — 14 Orleans, and more. Click here to see the tour dates. Burning Man/Dierks Bentley feat. Brothers Osbourne/Capital — 13 Chris Janson Receives BMI Million-Air Awards Night Shift/Jon Pardi/Capitol — 12 She Got The Best Of Me/Luke Combs/Columbia — 10 During Opry Appearance That Got The Girl/Casey Donahew/Almost Country Entertainment — 7 Blue Tacoma/Russell Dickerson/Triple Tigers — 7 On Deck—Soon To Be Charting song/artist/label—No. -

Country Update

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS MARCH 1, 2021 | PAGE 1 OF 18 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] What’s Up With Strait Talk With Songwriter Dean Dillon Bryan’s ‘Down’ >page 4 As He Awaits His Hall Of Fame Induction Academy Of Country Life-changing moments are not always obvious at the time minutes,” says Dillon. “I was in shock. My life is racing through Music Awards they occur. my mind, you know? And finally, I said something stupid, like, Raise Diversity So it’s easy to understand how songwriter Dean Dillon (“Ten- ‘Well, I’ve given my life to country music.’ She goes, ‘Well, we >page 10 nessee Whiskey,” “The Chair”) missed the 40th anniversary know you have, and we’re just proud to tell you that you’re going of a turning point in his career in February. He and songwriter to be inducted next fall.’ ” Frank Dycus (“I Don’t Need Your Rockin’ Chair,” “Marina Del The pandemic screwed up those plans. Dillon couldn’t even Rey”) were sitting on the front porch at Dycus’ share his good fortune until August — “I was tired FGL, Lambert, Clark home/office on Music Row when producer Blake of keeping that a secret,” he says — and he’s still Get Musical Help Mevis (Keith Whitley, Vern Gosdin) pulled over waiting, likely until this fall, to enter the hall >page 11 at the curb and asked if they had any material. along with Marty Stuart and Hank Williams Jr. He was about to record a new kid and needed Joining with Bocephus is apropos: Dillon used some songs. -

Patty Griffin Is Among the Most Consequential Singer-Songwriters Of

Patty Griffin is among the most consequential singer-songwriters of her generation, a quintessentially American artist whose wide-ranging canon incisively explores the intimate moments and universal emotions that bind us together. Over the course of two decades, the 2x GRAMMY® Award winner – and 7x nominee – has crafted a remarkable body of work in progress that prompted the New York Times to hail her for “[writing] cameo-carved songs that create complete emotional portraits of specific people…[her] songs have independent lives that continue in your head when the music ends.” 2019 saw the acclaimed release of the renowned artist’s GRAMMY® Award-winning 10th studio recording, PATTY GRIFFIN, on her own PGM Recordings label via Thirty Tigers. An extraordinary new chapter and one of the most deeply personal recordings of Griffin’s remarkable two-decade career, the album collects songs written during and in the aftermath of profound personal crisis, several years in which she battled - and ultimately defeated - cancer just as a similar and equally insidious disease metastasized into the American body politic. As always, Griffin’s power lies in how, as writer Holly Gleason observed in Martha’s Vineyard Gazette, “her songs seem to freeze life and truth in amber.” Griffin’s first-ever eponymous LP, PATTY GRIFFIN made a top 5 debut on Billboard’s “Independent Albums” chart amidst unprecedented worldwide acclaim – and later, a prestigious GRAMMY® Award for “Best Folk Album,” Griffin’s first win and second consecutive nomination in that category following 2015’s SERVANT OF LOVE. “A master class in vivid, empathetic roots music that’s both about taking responsibility for the choices we’ve made and surrendering to those made for us,” raved Entertainment Weekly. -

Pressed on 180 Gram HQ, This Specially Packaged Release Includes New Artwork and a Full CD of the Album

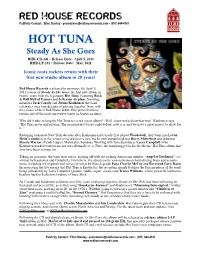

RED HOUSE RECORDS Publicity Contact: Ellen Stanley • [email protected] • (651) 644-4161 HOT TUNA Steady As She Goes RHR-CD-241 • Release Date: April 5, 2011 RHR-LP-241 • Release Date: May, 2011 Iconic roots rockers return with their first new studio album in 20 years! Red House Records is pleased to announce the April 5, 2011 release of Steady As She Goes, the first new album in twenty years from the legendary Hot Tuna. Featuring Rock & Roll Hall of Famers and Jefferson Airplane founding members Jack Casady and Jorma Kaukonen, the band celebrates over four decades of playing together. Now, with the release of their Red House debut, they prove that they remain one of the most innovative bands in American music. Why did it take so long for Hot Tuna to record a new album? “Well, it just worked out that way,” Kaukonen says. “Hot Tuna never quit playing. The moment just wasn’t right before; now it is, and we have a great project to show for it.” Returning to upstate New York decades after Kaukonen and Casady first played Woodstock, they went into Levon Helm’s studio over the winter to record twelve new tracks with mandolin player Barry Mitterhoff and drummer Skoota Warner (Cyndi Lauper, Matisyahu, Santana). Working with famed producer Larry Campbell (who Kaukonen worked with on his last solo album River of Time) the band plugged in for the electric Hot Tuna album that fans have been waiting for. Taking no prisoners, the band tears into it, kicking off with the rocking Americana number “Angel of Darkness” (co- written by Kaukonen and Campbell). -

Bobby Karl Works the 9Th Annual AMA Honors & Awards Chapter

page 1 Friday, September 10, 2010 Bobby Karl Works the 9th Annual AMA Honors & Awards Chapter 344 Americana music may be a fringe genre, financially struggling, lacking major media exposure and a complete mystery to most mainstream music consumers, but its awards 2010 Americana Honors show was a total celebration of its star power. & Awards Recipients Presented at the Ryman Auditorium on Thursday (9/9), the event featured Album Of The Year appearances by Rosanne Cash, Emmylou Harris, John Oates, Robert Plant, The List, Rosanne Cash Rodney Crowell, John Mellencamp, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Wanda Jackson Artist Of The Year and The Courtyard Hounds Martie Maguire and Emily Robison. And that doesn’t Ryan Bingham even count the star-studded “house band.” Instrumentalist Of The Year Musically, we knew we were in for a treat when Sam Bush and Will Kimbrough Buddy Miller led the festivities off with “Tumbling Dice,” featuring Buddy Miller, Jim Lauderdale, New/Emerging Artist Emmy and Patty Griffin in Hayes Carll support. Lauderdale has Song Of The Year seemingly been institutionalized “The Weary Kind” performed by Ryan as the show’s host. Bingham; written by Ryan Bingham “Welcome back, my and T Bone Burnett friends, to the show that Duo/Group Of The Year never ends….on time,” he The Avett Brothers quipped. This annual gig is, ••• indeed, renowned for punishing Jack Emerson Lifetime Achievement rear ends on the unforgiving Award For Executive: Luke Lewis wooden Ryman pew seats for Lifetime Achievement Award For four hours and more. Lauderdale Instrumentalist:Greg Leisz promised that he would run Lifetime Achievement Award For Performance:Wanda Jackson this year’s event on schedule, and he nearly succeeded. -

Buddy Miller and Jim Lauderdale

NOVEMBER 2012 ISSUE MMUSICMAG.COM REVIEWS HOLE BNobody’sUDDY MILLER Daughter AND JIM LAUDERDALE [Universal] Buddy and Jim [New West] The first album released under the Hole moniker since 1998’s Celebrity Skin is really frontwoman Courtney Love’sThe two brightest stars in Americana have found success with solo albums second solo album—co-founder,and written gems for giants like George Strait and the Dixie Chicks. They’ve songwriter and lead guitarist Eric Erlandson isn’t involved,also scored with collaborative efforts: Miller has played with Emmylou Harris nor is any other previous Hole member. So it’s Love andand three Robert Plant’s Band of Joy, while Lauderdale has recorded with Ralph ringers on 11 new songs—10 of which Love wroteStanley with and toured with Elvis Costello. This team-up album has been a long time collaborators like Billy Corgan,coming. Linda Comprising Perry and newbona fide classics and originals that sound like they could guitarist Micko Larkin. (Perry gets full credit on one tune, “Letter to God.”) be, Buddy and Jim is a freewheeling record, and the underlying grit makes it Much of the riveting intensity of the group’s 1990s heyday appears to havefeel left like along the with best her living former room Daniel Jackson jam session ever. Miller and Lauderdale draw from bandmates, but there are fl ashes here of the snarling Too often, though, the slower songs trip her up. While once fury Love deployed to suchsuch devastating close-singing effect back ’50s in the country day. they duos were as showcases Johnnie for and harrowing Jack, representeddisplays of naked here emotion, She spits out her vocals withwith vengeful a playful disdain cover on “Skinny of “South Little inLove New sounds Orleans,” more dispassionate complete thesewith days.Cajun The fiddle. -

SARA HAMILTON PUBLICITY ONESHEET.Pub

National Release Date: call my name June 21, 2005 Strange as it may sound, Sara Hamilton actually left Austin to become a song- writer. With degree in hand, she packed up her songwriting vocation in 2002 and headed Americana Radio Promo: for Texas’ other music hotbed, Dallas/Fort Worth, and the friendly confines of home in Al Moss/Melissa Farina Mansfield, Texas. There, she found a welcoming social structure that allowed her to qui- 615.297.0258 [email protected] etly sock away a bagful of solid tunes in the vein of waltz king Bruce Robison and ballad- eer Jim Lauderdale, while gaining experience behind the mic at coffeehouses, cigar joints and the occasional honky-tonk. Along the way, a chance introduction to a Texas music Booking/Management: insider led to a friendship and, eventually, to management representation. Steve Dieterichs Flash to the first of many “homeboy hookups” – a greasy-spoon meeting with 214.585.3523 multi-talented artist/producer/playwright Jesse Dayton. The “Country Soul Brother” booking@sarahamilton. quickly realized that there were enough stars in Sara’s songbook to make a “kickass, smart com Americana record.” Over flapjacks and caffeine, the “You could fill the Astrodome with pretty girls with pretty voices, but you’d be hard pressed plan for Call My Name was hatched, and to fill the batter’s box with songwriting talent pre-production of the project began on the like Sara Hamilton.” spot. Time was of the essence. Dayton had only a small window of opportunity for the project before a West Coast tour and the be- ginning of his next project, the score for the Rob Zombie movie The Devil’s Reject. -

Friday, November 16, 8Pm, 2007 Umass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall

Friday, November 16, 8pm, 2007 UMass Fine Arts Center Concert Hall Unbroken Chain: The Grateful Dead in Music, Culture, and Memory As part of a public symposium, November 16-18, UMass Amherst American Beauty Project featuring Jim Lauderdale Ollabelle Catherine Russell, Larry Campbell Theresa Williams Conceived by David Spelman Producer and Artistic Director of the New York premier Program will be announced from the stage Unbroken Chain is presented by the UMass Amherst Graduate School, Department of History, Fine Arts Center, University Outreach AND University Reserach. Sponsored by The Valley Advocate, 93.9 The River, WGBY TV57 and JR Lyman Co. About the Program "The American Beauty Project" is a special tribute concert to the Grateful Dead's most important and best-loved albums, Working Man's Dead and American Beauty. In January 2007, an all-star lineup of musicians that Relix magazine called "a dream team of performers" gave the premier of this concert in front of an over-flowing crowd at the World Financial Center's Winter Garden in New York City. The New York Times' Jon Pareles wrote that the concert gave "New life to a Dead classic... and mirrored the eclecticism of the Dead," and a Variety review said that the event brought "a back- porch feel to the canyons of Gotham's financial district. The perf's real fire came courtesy of acts that like to tear open the original structures of the source material and reassemble the parts afresh - an approach well-suited to the honorees' legacy." Now, a select group of those performers, including Ollabelle, Larry Campbell & Teresa Williams, Catherine Russell, and Jim Lauderdale are taking the show on the road. -

For Immediate Release November 2020 All My Shame

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NOVEMBER 2020 ALL MY SHAME, THE FIRST ALBUM IN EIGHT YEARS FROM SINGER/SONGWRITER MANDO SAENZ SET FOR RELEASE ON FEBRUARY 26TH VIA CARNIVAL RECORDING COMPANY/EMPIRE LISTEN TO PSYCHEDELIC NEW TRACK “IN ALL MY SHAME” HERE Nashville, TN – All My Shame, the long overdue new album from singer/songwriter Mando Saenz, will be released February 26th, 2021 (Carnival Recording Company/EMPIRE). Produced by former Wilco drummer / co-founder Ken Coomer, All My Shame is the first solo album in eight years from the multi-talented artist, and a project well worth the wait. The Saenz/Coomer creative partnership proved to be a fruitful one resulting in a dynamic new album featuring an expansive sonic direction for Saenz. All My Shame blends elements of rock, pop, folk and psychedelia with thoughtful balladry, infectious melodies and insightful lyrics. The title track “In All My Shame” will be released to all DSP’s on December 4th. LISTEN NOW Saenz spent the better part of the last fifteen years as a professional musician and songwriter in Nashville, penning songs that have been recorded by Lee Ann Womack, Miranda Lambert, Aubrie Sellers and Jim Lauderdale, to name a few. During that time, he released three folk/country-rock leaning solo albums (2005’s Watertown, 2008’s Bucket, 2013’s Studebaker) all with a touch of influence from his Texas musical heroes, where he spent much of his childhood. Throughout the recording of All My Shame, Saenz was on a mission to create an album unlike his previous work. His goal was fully realized as evidenced throughout the 11 new songs. -

Strait Talk February/March 1999

S T R A I T T A L K George Strait Country Music Festival Tour Is Set After months of preparation and planning, job of setting the pace for the days enter- showcase newer nationally known country all of the logistics and details have finally tainment. music talent. The stages will have talent been worked out for the 1999 George Strait Each show will also feature the performing each day before the stadium Country Music Festival Tour. It will begin “Straitland” entertainment area outside of show starts and during each one of the set on March 6th in Phoenix, AZ and wrap up the stadium. “Straitland” will consist of changes. Check your local schedules for on June 6th in Pittsburgh, PA. The tour will sponsor booths, food and beverage conces- the time that “Straitland” opens. In many consist of 18 shows in major athletic stadi- sion stands, vendors and a stage that will Continued on next page ums. The cities to be visited will include, in addition to Phoenix and Pittsburgh, El Paso, Tampa, Clemson, S.C., New Orleans, San Antonio, Houston, Dallas, Ames, IA, Chicago, Las Vegas, Oakland, Washington D.C., Foxboro, MA, Kansas City, Louisville, and Detroit. The stops in Washington and Foxboro will be the first in several years in the northeast. A complete itinerary can be found on the back page of the newsletter. Special fan club seating will be available at all locations. A story else- where in the newsletter will furnish all of the information. Joining George Strait on tour this year will be CMA “Album of the Year” winner, Tim McGraw and double CMA Award winners The Dixie Chicks.