As in the All the Other of Levi's Holocaust Poems I Discuss in This

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“IF THIS IS a MAN” the LIFE and LEGACY of PRIMO LEVI Wednesday and Thursday October 23 and 24, 2002

CALL FOR PAPERS HOFSTRA CULTURAL CENTER presents “IF THIS IS A MAN” THE LIFE AND LEGACY OF PRIMO LEVI Wednesday and Thursday October 23 and 24, 2002 Hofstra University is proud to sponsor an international conference on the life and philosophy of Primo Levi (1919-1987). His memoir, Survival in Auschwitz (If This Is a Man), has claimed a place among the masterpieces of Holocaust literature. Levi’s last work, The Drowned and the Saved, is arguably the most profound meditation on the Shoah. In his lifetime Levi forged an impressive body of work, and his writings remain a powerful reminder of what transpired in the extermination camps of Europe and what it means to be human after Auschwitz. We welcome paper proposals on any number of topics, including but not limited to: Levi and the Culture of Turin Levi and Italian Jews The Holocaust vs. the Culture of Science Memory and Holocaust Memoirs Language and Writing Levi, Theater and Film Representations of the Holocaust Suicide (?) Proposals for other presentations, lecture/demonstrations, panels, round-tables and workshops are also welcomed. A letter of intent, a three- to five-page abstract (in duplicate) and curriculum vitae should be sent by January 18, 2002, to: PRIMO LEVI CONFERENCE Hofstra Cultural Center (HCC) 200 Hofstra University Hempstead, New York 11549-2000 The deadline for completed double-spaced papers in duplicate is August 2, 2002. Presentation time for papers, lectures, lecture/demonstrations and workshops is limited to 20 minutes. (Papers should be limited to 10-12 typed, double- spaced pages, excluding notes.) As selected papers will be published in the conference proceedings, previously published material should not be submitted. -

Primo Levi and the Material World

Gerry Kearns1 If wood were an element: Primo Levi and the material world Abstract The precarious survival of a single shed from the Jewish slave labour quarters of the industrial complex that was Auschwitz- Monowitz offers an opportunity to reflect upon aspects of the materiality of the signs of the Holocaust. This shed is very likely ne that Primo Levi knew and its survival incites us to interrogate its materiality and significance by engaging with Levi’s own writings on these matters. I begin by explicating the ways the shed might function as an ‘encountered sign,’ before moving to consider its materiality both as a product of modernist genocide and as witness to the relations between precarity and vitality. Finally, I turn to the texts written upon the shed itself and turn to the performative function of Nazi language. Keywords Holocaust, icon, index, materiality, performativity, Primo Levi Fig. 1 - The interior of the shed, December 2012 (Photograph by kind permission of Carlos Reijnen) It is December 2012, we are near the town of Monowice in Poland. Alongside a small farmhouse, there is a hay-shed. The shed is in two parts with two doorways communicating and above these, “Eingang” and “Ausgang”. In the further part of the shed, there is more text, in Gothic font, in German. Along a crossbeam 1 National University of Ireland, Maynooth; [email protected]. I want to thank the directors of the Terrorscapes Project (Rob van der Laarse and Georgi Verbeeck) for the invitation to come on the field trip to Auschwitz. I want to thank Hans Citroen and Robert Jan van Pelt for their patient teaching about the history of the site. -

12. Exile As Dehumanization: Primo Levi

12. Exile as Dehumanization: Primo Levi Among those bearing witness, the Italian chemist and writer Primo Levi (b. 1919 in Turin, d. 1987 in Turin) stands out due to his thorough, sober, and analytical approach to the Holocaust. He was the author of many books, novels, collections of short stories, essays, and poems. His best-known works include If This is a Man (1947; US title, Survival in Auschwitz, 1959), his account of the year he spent as a prisoner in the Auschwitz concentration camp, The Truce (1963), The Periodic Table (1975), which linked Holocaust stories to the elements, and The Drowned and the Saved (1986). Levi became “the other” prominent voice in American Holocaust discourse during the 1980s. There is a huge body of literature comparing Primo Levi and Elie Wiesel. Of all Holocaust survivors, these two have become the most important voices, especially in the US, as their works were frequently written about in the New York Times Book Review, Publishers Weekly, the Hudson Review, World Literature Today, Newsweek, the Wall Street Journal, Time, The Nation, the New Republic, the Chicago Tribune, the Chicago Sun-Times Book Review, Atlantic Monthly, the LA Times Book Review, Vanity Fair, and other influential media. They have also been widely discussed by American academics and featured in Jewish and Holocaust courses. Paradoxically, they are not so well known in Central and Eastern Europe due to those areas’ cultural insulation during the Communist period. Levi had an urgent concern to communicate his experiences during the Holocaust to a broader public, as well as to future generations, and judging from his reception both in his native Italy and particularly in the US, we can say he succeeded. -

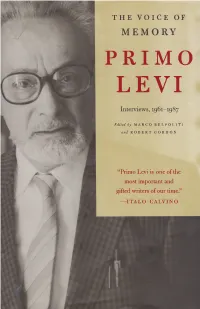

Primo-Levi-The-Voice-Of-Memory

THE VOICE OF MEMORY PRIMO LEVI Interviews, 1961-1987 Edited by M A R C 0 B E L P 0 L I T I and R 0 B E R T G 0 R D 0 N "Primo Levi is one of the most important and gifted writers of our time." -ITALO CALVINO The Voice of Memory The Voice of Memory Interviews 1961-1987 Primo Levi Edited by Marco Belpoliti and Robert Gordon Translated by Robert Gordon The New Press New York This collection © 2001 by Polity Press First published in Italy as Primo Levi: Conversazioni e interviste 1963-87, edited by Marco Belpoliti © 1997 Guilio Einaudi, 1997, with the exception of the interviews beginning on pages 3, 13, 23, and 34 (for further details see Acknowledgments page). All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher. First published in the United Kingdom by Polity Press in association with Blackwell Publishers Ltd, 2001 Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2001 Distributed by W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., New York ISBN 1-56584-645-1 (he.) CIP data available. The New Press was established in 1990 as a not-for-profit alternative to the large, commercial publishing houses currently dominating the book publishing industry. The New Press operates in the public interest rather than for private gain, and is committed to publishing, in innovative ways, works of educational, cultural, and community value that are often deemed insufficiently profitable. The New Press, 450West 41st Street, 6th floor, NewYork, NY 10036 www.thenewpress.com Set in Plantin Printed in the -

Historical Translatability

Historical Translatability Primo Levi Amongst the Snares of European History 1938– 1987 By Domenico S c a r p a (Turin) Taking his cue from the groundbreaking English translation of ›The Complete Works‹ of Primo Levi (recently published in America by Liveright) and focusing on Levi’s early writing, the author argues for the necessity of re-reading Primo Levi today, pleading for a new historical and chronological approach to his work. 1. I would like to begin with an explanation of the two dates in my subtitle, 1938 and 1987. 1938 is the year when the Fascist regime led by Mussolini passed rac- ist laws against Jews. This event not only put on Italian Jews the burden of an increasing self-consciousness, but it also marked the beginning of their “search for roots,” the construction of a cultural identity for the many of them who were not particularly religious or aware of their heritage or tradition. Primo Levi was himself such a secular Jew. More importantly, the racist laws of 1938 made Italian Jews aware of an im- pending catastrophe. 1938 brought about the recognition of a further dimen- sion in national and European history. Metaphorically speaking, 1938 broke the back of Italian historical continuity. Shattering Italian identity, it was the first of many fractures that were to occur in the decade to follow. There was the entry of Italy into World War II on June 10, 1940, the fall of the Fascist regime on July 25, 1943, the complete collapse and dissolution of the Italian state after the armistice with the Allies on September 8, 1943, the liberation and the victory of the Italian Resistance on April 25, 1945, the institution of the republic in 1946 and, finally, the writing and promulgation of the new constitution of the Repubblica Italiana in 1948. -

If This Is a Man/The Truce PDF Book

IF THIS IS A MAN/THE TRUCE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Primo Levi,Stuart Woolf | 400 pages | 04 Jul 2003 | Little, Brown Book Group | 9780349100135 | English | London, United Kingdom If This is a Man/The Truce PDF Book Even outside the camps, struggles are rarely waged by Lumpenproletariat. No way. A must-read if you truly want to attempt to understand what happened in the camps and how hard it was to come back afterwards. Or else, it is raining and it is also windy: but you know that this evening it is your turn for the supplement of soup, so that even today you find the strength to reach the evening. Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Thus all healthy prisoners were evacuated, in frightful conditions, in the direction of Buchenwald and Mauthausen, while the sick were abandoned to their fate. Unbelievable as this may seem, some people have either forgotten or never cared to find out. One of the most important works of the 20th century. They all knew they were going to die, in a matter of time, but it was better to make their last time on earth the least unpleasant possible. O Primo Basilio by Eca de Queiros. It is better to content oneself with other more modest and less exiting truths, those one acquires painfully, little by little and without shortcuts, with study, discussion, and reasoning, those that can we verified and demonstrated. The ideas they proclaimed were not always the same and were, in general, aberrant or silly or cruel. -

The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation1

eSharp Issue 5 Borders and Boundaries The Ethical Limitations of Holocaust Literary Representation1 Anna Richardson (University of Manchester) To Speak or Not To Speak One of the most famous and frequently cited dictums on Holocaust representation is Theodor Adorno’s statement that ‘to write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric’ (1982, p.34). Clearly Adorno is not merely speaking about the act of writing poetry, but rather the tension between ethics and aesthetics inherent in an act of artistic production that reproduces the cultural values of the society that generated the Holocaust. Adorno later qualified this statement, acknowledging that ‘suffering […] also demands the continued existence of the very art it forbids’ (1997, p.252). How then does one presume to represent something as extreme as the Holocaust, when in theory one cannot do so without in some way validating the culture that produced it? As Adorno notes: ‘When even genocide becomes cultural property in committed literature, it becomes easier to continue complying with the culture that gave rise to the murder’ (1997, pp.252-253). Coupled with this is the commonly held concept of the Holocaust as something that is ‘unspeakable’. As a number of scholars have noted, this is not true in the strictest sense of ‘unspeakability’, as much has been written, and indeed said, on the subject of the Holocaust. Even on the level of historical record, which methodologically adheres to hard fact and traditionally rejects survivor testimony as too ‘imaginative’:2 the verbal representability of facts suffices, in and of itself, to disprove the claim that the Holocaust is absolutely unspeakable. -

Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz

Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz Caroline Williams, Arts One March, 2013 SHEMA January, 1946 You who live safe In your warm houses, You who finD, returning in the evening, Hot fooD anD frienDly faces: Consider if this is a man Who works in the muD Who Does not know peace Who fights for a scrap of bread Who Dies because of a yes or a no. ConsiDer if this is a woman, Without hair anD without a name With no more strength to remember, Her eyes empty anD her womb colD Like a frog in winter. Or may your house fall apart, May illness impeDe you, May your chilDren turn their faces from you. The monstrous From: an interview with Primo Levi in 1979 – on the subject of concentraon camp guarDs at Auschwitz: “These were not monsters. I DiDn’t see a single monster in my Rme in the camp. Instead I saw people like you anD I who were acRng in that way because there was Fascism, Nazism in Germany. Were some form of Fascism or Nazism to return, there woulD be people, like us, who woulD act in the same way, everywhere. AnD the same goes for the vicRms, for the parRcular behaviour of the vicRms about which so much has been saiD ...” “Because that look was not one between two men; anD if I had known how completely to explain the nature of that look, which came as if across the glass winDow of an aquarium between two beings who live in Different worlDs, I woulD also have explaineD the essence of the great insanity of the thirD Germany.” (p. -

IF THIS IS a MAN” by Primo Levi Adapted for Radio by George Whalley from the Original “Se Questo È Un Uomo” and from a Translation by Stuart Woolf

0 1 “IF THIS IS A MAN” by Primo Levi adapted for radio by George Whalley from the original “Se questo è un uomo” and from a translation by Stuart Woolf 2 3 TECHNICAL NOTE PRODUCTION NOTE This is a story told in the first person by Primo Levi. His account of the events has three facets to The layout of this typescript is unlike the usual layout of a radio script. The narrative it: sometimes it is purely and simply narrative; sometimes it is descriptive, of scenes or customs commentary is typed continuously on the even-numbered pages: the action and dialogue are or conditions; sometimes it is reflective, pondering the meaning of the tale. These three facets are typed continuously on the odd-numbered pages; the intention is that the even-numbered and the indicated respectively by assigning his account variously to LEVI (N), LEVI (D), and LEVI (R), odd-numbered pages should be played simultaneously, creating a counterpoint between the and it is intended that each be perceptibly differentiated from the others by having its own narration and the events. This intention can be realised equally well on either stereophonic or special microphone pick-up. To some extent the categories overlap, and the degree of difference monaural radio: but in the latter medium the use of stereo tape is advisable, so that the narrative between them varies from one content to another: these shades of difference should be reflected and the events can be recorded on separate channels; this gives the producer an exact control by discreet modification of the pick-ups, as may seem most suitable in any given context. -

Primo Levi and the Holocaust in Italy Padua Program

LI 459/RN 459: Primo Levi And the Holocaust in Italy Padua Program Summer 2014 Professor Nancy Harrowitz, Dept. of Romance Studies Boston University This course focuses on the Italian Holocaust survivor Primo Levi, who contributed some of the most provocative and influential writings on the Holocaust. In confronting this catastrophic event, he employed a variety of interdisciplinary approaches: scientific, literary, theological and philosophical. We will discuss these perspectives within the broader context of the Holocaust in Italy, including the writings of Giorgio Bassani and Elie Wiesel. Trips to Levi’s hometown of Turin and to Bassani’s home in Ferrara are included, as are films based on the works of both authors. COURSE TEXTS: Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz The Reawakening The Drowned and the Saved (photocopies) Giorgio Bassani, short stories Doris Bergen, War and Genocide (second edition) Michael Morgan, essays (photocopies) COURSE REQUIREMENTS: Oral report: 15 minutes, copy of report to be turned in before report is given, 10% of the grade. First paper, 4 pages, 20%. Midterm exam, 20%, Second paper, 6 to 8 pages, 30% Class participation, 20%. Students are responsible for completing the assigned readings before class and coming to class with reading notes prepared to discuss them. Attendance is required. SCHEDULE: Week 1: Introduction to Primo Levi; Survival in Auschwitz; preface to The Drowned and the Saved (pp. 11-22); Elie Wiesel, A Plea for the Dead, photocopy. Discuss Bergen, War and Genocide. Week 2: Survival in Auschwitz. Film, “Primo.” Bergen. First paper due. Week 3: The Reawakening; film “The Truce.” Theological Approaches: Richard Rubenstein, ”The Making of a Rabbi,” (photocopy). -

CIUS Dornik PB.Indd

THE EMERGENCE SELF-DETERMINATION, OCCUPATION, AND WAR IN UKRAINE, 1917-1922 AND WAR OCCUPATION, SELF-DETERMINATION, THE EMERGENCE OF UKRAINE SELF-DETERMINATION, OCCUPATION, AND WAR IN UKRAINE, 1917-1922 The Emergence of Ukraine: Self-Determination, Occupation, and War in Ukraine, 1917–1922, is a collection of articles by several prominent historians from Austria, Germany, Poland, Ukraine, and Russia who undertook a detailed study of the formation of the independent Ukrainian state in 1918 and, in particular, of the occupation of Ukraine by the Central Powers in the fi nal year of the First World War. A slightly condensed version of the German- language Die Ukraine zwischen Selbstbestimmung und Fremdherrschaft 1917– 1922 (Graz, 2011), this book provides, on the one hand, a systematic outline of events in Ukraine during one of the most complex periods of twentieth- century European history, when the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires collapsed at the end of the Great War and new independent nation-states OF emerged in Central and Eastern Europe. On the other hand, several chapters of this book provide detailed studies of specifi c aspects of the occupation of Ukraine by German and Austro-Hungarian troops following the Treaty of UKRAINE Brest-Litovsk, signed on 9 February 1918 between the Central Powers and the Ukrainian People’s Republic. For the fi rst time, these chapters o er English- speaking readers a wealth of hitherto unknown historical information based on thorough research and evaluation of documents from military archives in Vienna, -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. I refer to the first anthology of Levi scholarship published in English, Rea- son and Light: Essays on Primo Levi, ed. Susan Tarrow (Ithaca, NY: Center for International Studies, Cornell University, 1990). 2. Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz: The Nazi Assault on Humanity, trans. Stu- art Woolf (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1996); Se questo è un uomo, rev. ed. (Turin: Einaudi, 1958); Primo Levi, The Drowned and the Saved, trans. Ray- mond Rosenthal (New York: Random House, 1989); I sommersi e i salvati (Turin: Einaudi, 1986). On the importance of Levi in American intellectual life, see Michael Rothberg and Jonathan Druker, “A Secular Alternative: Primo Levi’s Place in American Holocaust Discourse,” Shofar: An Interdisciplinary Journal of Jewish Studies 28, no. 1 (forthcoming). 3. Berel Lang, Act and Idea in the Nazi Genocide (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990), 195. In the chapter titled “Genocide and Kant’s Enlightenment,” Lang offers a careful, measured, and detailed assessment of the “affiliation” between Enlightenment ideas and the inner logic of Nazism (165–206). He takes possible objections to his thesis seriously, admitting that so many Nazi proclamations and policies claimed to be in sharp opposition to Enlighten- ment principles. However, he states, these objections “argue past rather than against the thesis posed here, which is based on the internal structure of ideas, not on what is said about them” (194). 4. See Immanuel Kant, Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals, ed. H. J. Patton (New York: Harper & Row, 1964). The categorical imperative states the follow- ing: “Act only on that maxim through which you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law” (30).