SFZC's Wind Bell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Buddhism in America

Buddhism in America The Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series Columbia Contemporary American Religion Series The United States is the birthplace of religious pluralism, and the spiritual landscape of contemporary America is as varied and complex as that of any country in the world. The books in this new series, written by leading scholars for students and general readers alike, fall into two categories: some of these well-crafted, thought-provoking portraits of the country’s major religious groups describe and explain particular religious practices and rituals, beliefs, and major challenges facing a given community today. Others explore current themes and topics in American religion that cut across denominational lines. The texts are supplemented with care- fully selected photographs and artwork, annotated bibliographies, con- cise profiles of important individuals, and chronologies of major events. — Roman Catholicism in America Islam in America . B UDDHISM in America Richard Hughes Seager C C Publishers Since New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © Columbia University Press All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Seager, Richard Hughes. Buddhism in America / Richard Hughes Seager. p. cm. — (Columbia contemporary American religion series) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN ‒‒‒ — ISBN ‒‒‒ (pbk.) . Buddhism—United States. I. Title. II. Series. BQ.S .'—dc – Casebound editions of Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid-free paper. -

Just This Is It: Dongshan and the Practice of Suchness / Taigen Dan Leighton

“What a delight to have this thorough, wise, and deep work on the teaching of Zen Master Dongshan from the pen of Taigen Dan Leighton! As always, he relates his discussion of traditional Zen materials to contemporary social, ecological, and political issues, bringing up, among many others, Jack London, Lewis Carroll, echinoderms, and, of course, his beloved Bob Dylan. This is a must-have book for all serious students of Zen. It is an education in itself.” —Norman Fischer, author of Training in Compassion: Zen Teachings on the Practice of Lojong “A masterful exposition of the life and teachings of Chinese Chan master Dongshan, the ninth century founder of the Caodong school, later transmitted by Dōgen to Japan as the Sōtō sect. Leighton carefully examines in ways that are true to the traditional sources yet have a distinctively contemporary flavor a variety of material attributed to Dongshan. Leighton is masterful in weaving together specific approaches evoked through stories about and sayings by Dongshan to create a powerful and inspiring religious vision that is useful for students and researchers as well as practitioners of Zen. Through his thoughtful reflections, Leighton brings to light the panoramic approach to kōans characteristic of this lineage, including the works of Dōgen. This book also serves as a significant contribution to Dōgen studies, brilliantly explicating his views throughout.” —Steven Heine, author of Did Dōgen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It “In his wonderful new book, Just This Is It, Buddhist scholar and teacher Taigen Dan Leighton launches a fresh inquiry into the Zen teachings of Dongshan, drawing new relevance from these ancient tales. -

Buddhist Bibio

Recommended Books Revised March 30, 2013 The books listed below represent a small selection of some of the key texts in each category. The name(s) provided below each title designate either the primary author, editor, or translator. Introductions Buddhism: A Very Short Introduction Damien Keown Taking the Path of Zen !!!!!!!! Robert Aitken Everyday Zen !!!!!!!!! Charlotte Joko Beck Start Where You Are !!!!!!!! Pema Chodron The Eight Gates of Zen !!!!!!!! John Daido Loori Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind !!!!!!! Shunryu Suzuki Buddhism Without Beliefs: A Contemporary Guide to Awakening ! Stephen Batchelor The Heart of the Buddha's Teaching: Transforming Suffering into Peace, Joy, and Liberation!!!!!!!!! Thich Nhat Hanh Buddhism For Beginners !!!!!!! Thubten Chodron The Buddha and His Teachings !!!!!! Sherab Chödzin Kohn and Samuel Bercholz The Spirit of the Buddha !!!!!!! Martine Batchelor 1 Meditation and Zen Practice Mindfulness in Plain English ! ! ! ! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana The Four Foundations of Mindfulness in Plain English !!! Bhante Henepola Gunaratana Change Your Mind: A Practical Guide to Buddhist Meditation ! Paramananda Making Space: Creating a Home Meditation Practice !!!! Thich Nhat Hanh The Heart of Buddhist Meditation !!!!!! Thera Nyanaponika Meditation for Beginners !!!!!!! Jack Kornfield Being Nobody, Going Nowhere: Meditations on the Buddhist Path !! Ayya Khema The Miracle of Mindfulness: An Introduction to the Practice of Meditation Thich Nhat Hanh Zen Meditation in Plain English !!!!!!! John Daishin Buksbazen and Peter -

14492514 Lese 1.Pdf

Das Buch Shunryû Suzuki ist der wohl bedeutendste Zen-Meister der Neuzeit. Sein Wirken hinterließ eine tiefe Erinnerungsspur im Bewußtsein aller Menschen, die eine echte und freie spirituelle Erfahrung suchten. Der »alte Meister« tat seine Botschaft mit unerbittlicher Konsequenz, aber auch mit ergreifender Warmherzigkeit kund. Glanzpunkte spiritueller Inspiration waren seine täglichen Darlegungen der Lehre vor den Schülern. Ganz aus dem Geiste des Zen geboren, ergaben sie sich in der Regel spontan und ohne vorheriges Konzept. In diesem Buch sind sie in ihrer ursprünglichen Form wieder- gegeben. Suzukis kauzige Weisheit, seine verständliche, bisweilen provozierende Art, die Menschen wachzurütteln und auf den Weg der Erleuchtung zu führen, sind einzigartig und unverwechselbar. Der Autor Shunryû Suzuki (1904 bis 1971) wurde in jungen Jahren in seinem Heimatland Japan buddhistischer Mönch, später Tempelpriester. Sein welt- weites Wirken als spiritueller Lehrer begann 1959, als er als Meditations- lehrer nach Amerika ging. In San Francisco gründete er das erste Zen- Zentrum des Westens, später das legendäre Zen-Kloster Tassajara in den kalifornischen Bergen. Der Rôshi (»alte Meister«), wurde zu einem geistigen Mittelpunkt der blühenden kulturellen Szene der 60er-Jahre an der West- küste Amerikas. Zu seinen Schülern und Verehrern gehörten berühmte Künstler und Prominente, vor allem aber auch ungezählte junge Menschen, die sich nach einem Leben sehnten, in dem innere Werte und spirituelle Ziele wieder eine Rolle spielten. Shunryû Suzuki SEID WIE REINE SEIDE UND SCHARFER STAHL Das geistige Vermächtnis des großen Zen-Meisters Herausgegeben von Edward Espe Brown Aus dem Englischen von Stephan Schuhmacher WILHELM HEYNE VERLAG MÜNCHEN Die amerikanische Originalausgabe erschien 2002 unter dem Titel »Not Always So« im Verlag HarperCollins Publishers in New York, USA. -

Family and Society a Buddhist

FAMILY AND SOCIETY: A BUDDHIST PERSPECTIVE ADVISORY BOARD His Holiness Thich Tri Quang Deputy Sangharaja of Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Thich Thien Nhon President of National Vietnam Buddhist Sangha Most Ven.Prof. Brahmapundit President of International Council for Day of Vesak CONFERENCE COMMITTEE Prof. Dr. Le Manh That, Vietnam Most Ven. Dr. Dharmaratana, France Most Ven. Prof. Dr. Phra Rajapariyatkavi, Thailand Bhante. Chao Chu, U.S.A. Prof. Dr. Amajiva Lochan, India Most Ven. Dr. Thich Nhat Tu (Conference Coordinator), Vietnam EDITORIAL BOARD Dr. Do Kim Them, Germany Dr. Tran Tien Khanh, U.S.A. Nguyen Manh Dat, U.S.A. Bruce Robert Newton, Australia Dr. Le Thanh Binh, Vietnam Giac Thanh Ha, Vietnam Nguyen Thi Linh Da, Vietnam Tan Bao Ngoc, Vietnam Nguyen Tuan Minh, U.S.A. VIETNAM BUDDHIST UNIVERSITY SERIES FAMILY AND SOCIETY: A BUDDHIST PERSPECTIVE Editor Most Ven. Thich Nhat Tu, D.Phil., HONG DUC PUBLISHING HOUSE Contents Foreword ................................................................................................... ix Preface ....................................................................................................... xi Editors’ Introduction ............................................................................ xv 1. Utility of Buddhist Meditation to Overcome Physical Infirmity and Mental Disorders Based on Modern Neuroscience Researches Ven. Polgolle Kusaladhamma ..........................................................................1 2. The Buddhist Approach Toward an Ethical and Harmonious Society Jenny -

The SZBA Was Initially Proposed at the Last Tokubetsu Sesshin in America in 1995

The SZBA was initially proposed at the last Tokubetsu sesshin in America in 1995. The thought was to form an American association in relation to the Japanese Sotoshu but autonomous. At the time of its initial formation in 1996, the SZBA consisted of Maezumi-roshi and Suzuki-roshi lineages. The founding Board members were Tenshin Reb Anderson, Chozen Bays, Tetsugen Glassman, Keido Les Kaye, Jakusho Kwong, Daido Loori, Genpo Merzel, and Sojun Mel Weitsman. Generating interest in the organization was difficult. After a dormant period during which Sojun Mel Weitsman held the organization, a new Board was empowered in 2001 and started meeting regularly in 2002. Keido Les Kaye continued on the Board and was joined by Eido Carney, Zoketsu Norman Fischer, Misha Merrill, Myogen Stucky, and Jisho Warner. This group revised the By-laws and moved forward to publish a roster of members, create a website and hold a National Conference. Around 50 attendees came to the first National Conference that took place in 2004, and ten lineages were represented. Some of these lineages passed through teachers who were pivotal in establishing Soto Zen in America by teaching and leading Sanghas on American soil such as Tozen Akiyama, Kobun Chino, Dainin Katagiri, Jiyu Kennett, Taizan Maezumi, and Shunryu Suzuki, and some passed through teachers who remained in Japan yet were also important in establishing Soto Zen in America in both small and large ways, including Daito Noda, Tetsumei Niho, Gudo Nishijima, and Butsugen Joshin. It was an inspiring conference, working committees were formed, and a new Board was established. -

Literaturverzeichnis

Literaturverzeichnis Im Buch gibt es keine Fußnoten nur teilweise Literaturhinweise im Text. Und dies ist eine besondere Art von Literatur- und Filmverzeichnis. Warum dies? Hinweis zum Literaturverzeichnis Hinweise auf die Veröffentlichungen anderer, Fußnoten, aus denen hervorgeht, von wem man etwas übernommen hat, das sind eigentlich sinnlose Unternehmen. Dies gilt insbesondere bei einem Buch wie die- sem hier. Wo fängt man an mit den Hinweisen auf andere, wenn man der Auffas- sung ist, auch auf sehr allgemeine Erkenntnisse Bezug nehmen zu müssen? Wo hört man auf, bei welcher Ebene von Details meist technischer Art, auf die sich andere bezogen haben, um etwas zu erarbeiten? Es geht immer darum, zu prüfen, wer etwas zuerst gesagt hat. Was aber heißt gesagt? Gesagt heißt in diesem Zusammenhang etwas anderes, nämlich schriftlich festgehalten. Etwas muss irgendwo schriftlich, typischerweise in einer wissenschaft- lichen Zeitschrift oder in einem Buch, festgehalten sein, um als Veröffentlichung zu gelten. Doch wenn jemand etwas in Anwesenheit anderer tatsächlich gesagt hat, ist das nicht auch veröffentlicht, und fordert der Betreffende dann nicht mit Recht, dass sein nur mündlich geäußerter Gedanke, eine Hypothese etwa, von anderen entspre- chend gewürdigt wird? Ist zudem das, was in den sozialen Medien verbreitet wird, als eine Veröffentlichung zu werten? Eigentlich schon, schließlich ist es ja öffentlich. Es ist einfach viel zu viel öffentlich. Ich kann nicht mehr genau sagen, was ich wo aufgegriffen habe, mir notiert habe, woher möglicherweise ein Gedanke kommt. Jede Idee, die ich hier ausbreite, könnte von anderen übernommen sein; es ist aber auch nicht ausgeschlossen, dass manches von mir ist. Nehmen wir einmal das Ge- biet der Hirnforschung, auf dem jedes Jahr 100.000 wissenschaftliche Publikationen erscheinen; genau gezählt hat das niemand. -

Masks — Anthropology on the Sinhalese Belief System

MASKS:MASKS: AnthrAnthropologyopology onon thethe SinhaleseSinhalese BeliefBelief SystemSystem David Blundell Ph.D. HAN DD ET U 'S B B O RY eOK LIBRA E-mail: [email protected] Web site: www.buddhanet.net Buddha Dharma Education Association Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blundell, David. Masks : anthropology on the Sinhalese belief system / David Blundell. p. cm. — (American university studies. Series VII, Theology and religion; vol. 88) Includes bibliographical references (p. ) 1. Sri Lanka—Religion—20th century. 2. Sri Lanka—Social life and customs. 3. Ethnology—Biographical methods. I. Title. II. Series. BL2032.S55B58 1994 306.6’095493—dc20 91-36067 ISBN 0–8204-1427-1 CIP ISSN 0740–0446 Die Deutsche Bibliothek-CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Blundell, David. Masks : anthropology on the Sinhalese belief system / David Blundell.—New York; Berlin; Bern; Frankfurt/M.; Paris; Wien: Lang, 1994 (American university studies: Ser. 7, Theology and Religion; vol. 88) ISBN 0–8204–1427–1 NE: American university studies/07 Cover design by George Lallas. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. © Peter Lang Publishing, Inc., New York 1994 All rights reserved. Reprint or reproduction, even partially, in all forms such as microfilm, xerography, microfiche, microcard, and offset strictly prohibited. Printed in the United States of America. David Blundell Masks Anthropology on the Sinhalese Belief System American University Studies Series VII Theology and Religion Vol. 88 PETER LANG New York • San Francisco • Bern • Baltimore Frankfurt am Main • Berlin • Wien • Paris Contents Figures List ..........................................................................................................viii Foreword: An Anthropology of Sharing ................................................ -

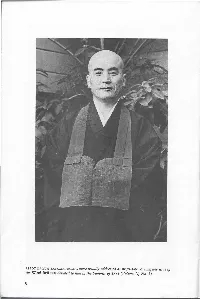

The Wind Bell Was Devoted 10 Him in 1He Summer of 1971 ( Volume X, No

ABBOT OAININ KATAGIRI-ROSHI, more usually addressed as HOJO-SAN. A complete issue of the Wind Bell was devoted 10 him in 1he Summer of 1971 ( Volume X, No. 1). 8 ZEN CENTER NEWS On December 20, 1983, Richard Baker-roshi resigned as Abbot of San Francisco Zen Center. The events which led up to this decision were outlined in the Winter 1983 Wind Bell. In his letter to Zen Center students and friends, Baker-roshi said: I have waited all these months trying to decide what to do because I did not know what to do to fulfill the vow I made to Suzuki-roshi to continue and to develop a place for his teaching which would endure. Now I see that my role as Abbot and leader is more damaging to the Sangha and to individuals than any help I may add by staying. And I see even more that the present situation and any effort I make in it is damaging to the teaching and this is completely unacceptable to me. I want to do what is best for Zen Center and the lineage and the teaching. And I want to do whatever I can to lessen, co end the deep suffering and pain many persons feel. So it is with deep regret and shame before Suzuki-roshi and you that I resign as Abbot and Chief Priest of the San Francisco Zen Center. I resign with trust and hope in your wisdom, in the strength of your future, and in the compassion and intelligence of each of you and of all of you working together. -

Transpacific Transcendence: the Buddhist Poetics of Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen

TRANSPACIFIC TRANSCENDENCE: THE BUDDHIST POETICS OF JACK KEROUAC, GARY SNYDER, AND PHILIP WHALEN BY Copyright 2010 Todd R. Giles Ph.D., University of Kansas 2010 Submitted to the graduate degree program in English and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ______________________________ Chair, Joseph Harrington ______________________________ Kenneth Irby ______________________________ Philip Barnard ______________________________ James Carothers ______________________________ Stanley Lombardo Date Defended: September 8, 2010 ii The Dissertation Committee for Todd R. Giles certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: TRANSPACIFIC TRANSCENDENCE: THE BUDDHIST POETICS OF JACK KEROUAC, GARY SNYDER, AND PHILIP WHALEN Committee: ______________________________ Chair, Joseph Harrington ______________________________ Kenneth Irby ______________________________ Philip Barnard ______________________________ James Carothers ______________________________ Stanley Lombardo Date Approved: September 8, 2010 iii Abstract "Transpacific Transcendence: The Buddhist Poetics of Jack Kerouac, Gary Snyder, and Philip Whalen," directed by Joseph Harrington, examines the influence of East Asian literature and philosophy on post-World War II American poetry. Kerouac's "Desolation Blues," Snyder's "On Vulture Peak," and Whalen's "The Slop Barrel" were all written one year after the famous Six Gallery reading in San Francisco where Allen Ginsberg -

Some Early Pages of Snail

- Mountain/Snail 5 Contents Foreword: David Chadwick --- -----·------ . Introduction: Lester Kaye-roshi Prologue Part I Zen L 'v 1 Zen Pioneers v" 2 Haiku ZendcS 3 Tassajara [,,,,·· 4 Zen Mistakes Part II Zen Tea l Zen Heart Mind v 2 Zen Breath / :,/ 3 Second Wind , ' _, v 4 Cushion or chair? Part III Zen Practice \// 1 Moment by Moment Meditation 2 Sitting Meditation 3 Moving Meditation 4 Moving Mindfulness 5 Hybrid Zen Epilogue Appendix Optional Exercises Glo.s.sary C~edits and Notes Index Mountain/Smnail Prologue The only way is to enJOY your life. Even though you are practicing zazen, counting your breaths like a snail, you can enjoy your life, maybe better than making a trip to the moon. That is why we practice zazen. Shunryu Suzuki Snail Zen is an offshoot of four decades of Zen practice that began when I was a 41 year-old, divorced mother of five teenage children. At this pivital point in my life my karma moved me, and moved an enlightened Japanese Zen Buddhist priest to meet and form a relationship that dramatically changed the course of my life. During the twelve years that Shunryu Suzuki devoted to his missionary work in the United States, he founded the San Fran cisco Zen Center, Tassajara Monastery and left a lasting legacy in a book that has become a Zen classic. Millions of readers around the world hav e received their first true taste of the fruit of Buddha's Bodhi tree preserved on the pages of Zen Mind, 1 Beg inner' s Mind , a. -

The New Buddhism: the Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition

The New Buddhism: The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS the new buddhism This page intentionally left blank the new buddhism The Western Transformation of an Ancient Tradition James William Coleman 1 1 Oxford New York Auckland Bangkok Buenos Aires Cape Town Chennai Dar es Salaam Delhi Hong Kong Istanbul Karachi Kolkata Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Mumbai Nairobi São Paulo Shanghai Singapore Taipei Tokyo Toronto and an associated company in Berlin Copyright © 2001 by James William Coleman First published by Oxford University Press, Inc., 2001 198 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, 10016 First issued as an Oxford University Press paperback, 2002 Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Oxford University Press. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Coleman, James William 1947– The new Buddhism : the western transformation of an ancient tradition / James William Coleman. p. cm. Includes index. ISBN 0-19-513162-2 (Cloth) ISBN 0-19-515241-7 (Pbk.) 1. Buddhism—United States—History—20th century. 2. Religious life—Buddhism. 3. Monastic and religious life (Buddhism)—United States. I.Title. BQ734.C65 2000 294.3'0973—dc21 00-024981 1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2 Printed in the United States of America Contents one What