Problems and Strategies for Private Sector Development in Akwa Ibom State, Nigeria

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

Inequality and Development in Nigeria Inequality and Development in Nigeria

INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA INEQUALITY AND DEVELOPMENT IN NIGERIA Edited by Henry Bienen and V. P. Diejomaoh HOLMES & MEIER PUBLISHERS, INC' NEWv YORK 0 LONDON First published in the United States of America 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. 30 Irving Place New York, N.Y. 10003 Great Britain: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Ltd. 131 Trafalgar Road Greenwich, London SE 10 9TX Copyright 0 1981 by Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. ALL RIGIITS RESERVIED LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria. Selections. Inequality and development in Nigeria. "'Chapters... selected from The Political economy of income distribution in Nigeria."-Pref. Includes index. I. Income distribution-Nigeria-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Nigeria- Economic conditions- Addresses. essays, lectures. 3. Nigeria-Social conditions- Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Bienen. Henry. II. Die jomaoh. Victor P., 1940- III. Title. IV. Series. HC1055.Z91516 1981 339.2'09669 81-4145 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA ISBN 0-8419-0710-2 AACR2 MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA Contents Page Preface vii I. Introduction 2. Development in Nigeria: An Overview 17 Douglas Riummer 3. The Structure of Income Inequality in Nigeria: A Macro Analysis 77 V. P. Diejomaoli and E. C. Anusion wu 4. The Politics of Income Distribution: Institutions, Class, and Ethnicity 115 Henri' Bienen 5. Spatial Aspects of Urbanization and Effects on the Distribution of Income in Nigeria 161 Bola A veni 6. Aspects of Income Distribution in the Nigerian Urban Sector 193 Olufemi Fajana 7. Income Distribution in the Rural Sector 237 0. 0. Ladipo and A. -

About Major Oil Marketers Association of Nigeria

December 2018 | Issue 01 About Major Oil Marketers Association of Nigeria Major Oil Marketers Association of Nigeria is the Nigerian energy consumer by partnership a downstream oil & gas industry group made with stakeholders including government and up of: 11Plc (formerly Mobil), Conoil Plc, Forte industry regulators. Oil Plc, MRS Oil Nigeria Plc, OVH Energy Marketing Limited and Total Nigeria Plc. On June 12th 2018 MOMAN announced the The Association is committed to help drive retirement of the former Executive Secretary, best practices and create the right policy Mr. Thomas Obafemi Olawore after 17 years environment for the achievement of market of service, and the appointment of the new objectives and the delivery of optimal value to Executive Secretary, Mr. Clement Isong. Inside this issue • New MOMAN • Safety Moments • Professional Profile Feature MOMAN is an acronym for Major Oil Marketers Association of Nigeria. It consists of 6 member companies. The New MOMAN Since its inception, MOMAN has progressively partnership with MDAs such as NNPC, PPMC, DPR, gained a solid and enviable reputation in PPPRA, FRSC, etc., through several programs, to the Nigerian Petroleum industry. MOMAN develop and promote HSEQ standards in the began in the early 2000’s as ‘CORDINATION’. industry, drive business efficiencies, identify The lack of investment in the country’s logistics opportunities and lead the industry in infrastructure, the quality of the distribution raising and meeting international standards and network, the changes in international make meaningful contributions to the society. A petroleum economics, or simply the inability few of which are stated below: to keep abreast with HSEQ developments in other parts of the world, (including • Engagement with PTD and transporters other African countries) have plagued the (through a taskforce set up by the Federal Government), to ensure the use of trucks Nigerian petroleum industry, resulting in an holding bays, thereby freeing the access unsustainable business model. -

Hospital Cash Approved Providers List

HOSPITAL CASH APPROVED PROVIDERS LIST S/N PROVIDER NAME ADDRESS REGION STATE 1 Life care clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street Aba, Aba Abia 2 New Era Hospital 213/215 Azikiwe Road, Aba Aba Abia 3 J-Medicare Hospital 73, Bonny Street, Umuahia By Enugu Road Umuahia Abia 4 New Era Hospital 90B Orji River Road, Umuahia Umuahia Abia 10,Mobolaji Johnson street,Apo Quarters,Zone Abuja Abuja 5 Rouz Hospital & Maternity D,2nd Gate,Gudu District 6 Sisters of Nativity Hospital Phase 1, Jikwoyi, abuja municipal Area Council Abuja Abuja 7 Royal Lords Hospital, Clinics & Maternity Ltd Plot 107, Zone 4, Dutse Alhaji, Abuja Dutse Alhaji Abuja 8 Adonai Hospital 3, Adonai Close, Mararaba, Garki Garki Abuja Plot 202, Bacita Close, Off Plateau Street, Area 2 , Garki Abuja 9 Dara Clinics Garki FHA Lugbe FHA Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 10 PAAFAG Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre 11 Central Hospital, Masaka Masaka Masaka Abuja 12 Pan Raf Hospital Limited Nyanya Phase 4 Nyanya Abuja Ahoada Close, By Nta Headquarters, Besides Uba, Abuja Abuja 13 Kinetic Hospital Area 11 14 Lona City Care Hospital 48, Transport Abuja Abuja Plot 145, Kutunku, Near Radio House, Gwagwalada Abuja 15 Jerab Hospital Gwagwalada 16 Paakag Hospital & Medical Diagnosis Centre Fha Lugbe, Fha Estate, Lugbe, Abuja Lugbe Abuja 17 May Day Hospital 1, Mayday Hospital Street, Mararaba, Abuja Mararaba Abuja 18 Suzan Memorial Hospital Uphill Suleja, Near Suleja Club, Gra, Suleja Suleja Abuja 64, Moses Majekodunmi Crescent,Utako, Abuja Utako Abuja 19 Life Point Medical Centre 7, Sirasso Close, Off Sirasso Crescent, Zone 7, Wuse Abuja 20 Health Gate Hospital Wuse. -

The Nigerian Energy Sector an Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification

European Union Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP) The Nigerian Energy Sector An Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification 2nd Edition, June 2015 Implemented by 2 Acknowledgements This report on the Nigerian energy sector was compiled as part of the Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP). NESP is implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH and fund- ed by the European Union and the German Federal Min- istry for Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ). The authors would like to thank the GIZ Nigeria team for having entrusted this highly relevant subject to GOPA- International Energy Consultants GmbH, and for their extensive and dedicated inputs and guidance provided during implementation. The authors express their grati- tude to all project partners who provided particularly val- uable and interesting insights into ongoing activities dur- ing the course of the project. It was a real pleasure and a great help to exchange ideas and learn from highly expe- rienced management and staff and committed represent- atives of this programme. How to Read Citations Bibliography is cited by [Author; Year]. Where no author could be identified, we used the name of the institution. The Bibliography is listed in Chapter 10. Websites (internet links) are cited with a consecutive numbering system [1], [2], etc. The Websites are listed in Chapter 11. 3 Imprint Published by: Maps: Deutsche Gesellschaft für The geographical maps are for informational purposes Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ) GmbH only and do not constitute recognition of international boundaries or regions; GIZ makes no claims concerning Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP) the validity, accuracy or completeness of the maps nor 2 Dr Clement Isong Street, Asokoro does it assume any liability resulting from the use of the Abuja / Nigeria information therein. -

A Critical Analysis of Transition to Civil Rule in Nigeria & Ghana 1960 - 2000

A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF TRANSITION TO CIVIL RULE IN NIGERIA & GHANA 1960 - 2000 BY ESEW NTIM GYAKARI DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA DECEMBER, 2001 A CRITICAL ANALYSIS OF TRANSITION TO CIVIL RULE IN NIGERIA & GHANA 1960 - 2000 BY ESEW NTIM GYAKARI (PH.D/FASS/06107/1993-94) BEING A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (PH.D) IN POLITICAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE, FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES, AHMADU BELLO UNIVERSITY, ZARIA. DECEMBER, 2001. DEDICATION TO ETERNAL GLORY OF GOD DECLARATION I, ESEW, NTIM GYAKARI WITH REG No PH .D/FASS/06107/93-94 DO HEREBY DECLARE THAT THIS DISSERTATION HAS BEEN PREPARED BY ME AND IT IS THE PRODUCT OF MY RESEARCH WORK. IT HAS NOT BEEN ACCEPTED IN ANY PREVIOUS APPLICATION FOR A DEGREE. ALL QUOTATIONS ARE INDICATED BY QUOTATION MARKS OR BY INDENTATION AND ACKNOWLEDGED BY MEANS OF REFERENCES. CERTIFICATION This dissertation entitled A Critical Analysis Of Transition To Civil Rule In Nigeria And Ghana 1960 - 2000' meets the regulation governing the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D) Political Science of Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria and is approved for its contribution to knowledge and literary presentation. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Any serious intellectual activity such as this could hardly materialize without reference to works by numerous authors. They are duly acknowledged with gratitude in the bibliography. My heartfelt gratitude goes to my Supervisors, Dr Andrew Iwini Ohwona (Chairman) and Dr Ejembi A Unobe. -

THE ORIGIN of the NAME NIGERIA Nigeria As Country

THE ORIGIN OF THE NAME NIGERIA Help our youth the truth to know Nigeria as country is located in West In love and Honesty to grow Africa between latitude 40 – 140 North of the And living just and true equator and longitude 30 – 140 East of the Greenwich meridian. Great lofty heights attain The name Nigeria was given by the Miss To build a nation where peace Flora Shaw in 1898 who later married Fredrick Lord Lugard who amalgamated the Northern And justice shall reign and Southern Protectorates of Nigeria in the NYSC ANTHEM year 1914 and died in 1945. Youth obey the Clarion call The official language is English and the Nation’s motto is UNITY AND FAITH, PEACE AND Let us lift our Nation high PROGRESS. Under the sun or in the rain NATIONAL ANTHEM With dedication, and selflessness Arise, O Compatriots, Nigeria’s call obey Nigeria is ours, Nigeria we serve. To serve our fatherland NIGERIA COAT OF ARMS With love and strength and faith Representation of Components The labour of our hero’s past - The Black Shield represents the good Shall never be in vain soil of Nigeria - The Eagle represents the Strength of To serve with heart and Might Nigeria One nation bound in freedom, - The Two Horses stands for dignity and pride Peace and unity. - The Y represent River Niger and River Benue. THE PLEDGE THE NIGERIAN FLAG I Pledge to Nigeria my Country The Nigeria flag has two colours To be faithful loyal and honest (Green and White) To serve Nigeria with all my strength - The Green part represents Agriculture To defend her unity - The White represents Unity and Peace. -

Inside NNPC Oil Sales: a Case for Reform in Nigeria

Inside NNPC Oil Sales: A Case for Reform in Nigeria Aaron Sayne, Alexandra Gillies and Christina Katsouris August 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors would like to thank those who reviewed the report. Lee Bailey, Dauda Garuba, Patrick Heller, Daniel Kaufmann and several industry experts offered valuable comments. We are also grateful to various experts, industry personnel and officials who provided insights and information for this research project. Cover image by Chris Hondros, Getty Images CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ........................................................................................................ 2 OVERVIEW DIAGRAM ..........................................................................................................12 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................13 OBJECTIVES AND METHODOLOGY .............................................................................14 THE BASICS OF NNPC OIL SALES ................................................................................16 REFORM IN THE CURRENT CONTEXT .......................................................................20 TARGETING URGENT PROBLEMS WITH NNPC CRUDE SALES ..................29 Issue 1: The Domestic Crude Allocation (DCA) ................................30 Issue 2: Revenue retention by NNPC and its subsidiaries ............34 Issue 3: Oil-for-product swap agreements ........................................42 Issue 4: The abundance of middlemen ..............................................44 -

The Nigerian Energy Sector

The Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP) The Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP) The Nigerian Energy Sector - an Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy The NigerianEfficiency Energy and Rural Sector Electrification - an Overview withNovember, a Special 2014 Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification The Nigerian Energy Sector - an Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification November, 2014 Implemented by Implemented by 20141121_Energy Sector Study_NESP Publication draft_v2.docx The Nigerian Energy Sector - an Overview with a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, The Nigerian Energy Sector - an Overview with Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification a Special Emphasis on Renewable Energy, Energy Efficiency and Rural Electrification 20141121_Energy Sector Study_NESP Publication draft_v2.docx 20141121_Energy Sector Study_NESP Publication draft_v2.docx 2 Acknowledgements This report on the Nigerian Energy Sector was financed by the German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooper- ation and Development (BMZ) and implemented by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenar- beit (GIZ) GmbH under the Nigerian Energy Support Programme (NESP). The authors would like to thank the GIZ Nigeria team for having entrusted this highly relevant subject to GOPAInternational Energy Consultants GmbH, and for their extensive and dedicated inputs and guidance pro- vided during implementation. The authors express their gratitude to all project -

Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files BIAFRA-NIGERIA

A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files BIAFRA-NIGERIA 1967–1969 POLITICAL AFFAIRS A UPA Collection from Confidential U.S. State Department Central Files BIAFRA-NIGERIA 1967–1969 POLITICAL AFFAIRS Subject-Numeric Categories: POL Project Coordinator Robert E. Lester Guide compiled by Jeffrey T. Coster A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road • Bethesda, MD 2081420814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Biafra-Nigeria, 1967–1969 [microform]: subject-numeric categories—AID, CSM, DEF, and POL / project coordinator, Robert E. Lester. microfilm reels. Accompanied by a printed guide compiled by Jeffrey T. Coster. ISBN 0-88692-756-0 1. Nigeria—History—Civil War, 1967–1970—Sources. 2. Nigeria, Eastern— History—20th century—Sources. 3. Nigeria—Politics and government— 1960—Sources. 4. United States—Foreign relations—Nigeria—Sources. 5. Nigeria—Foreign relations—United States—Sources. 6. United States. Dept. of State—Archives. I. Lester, Robert. II. Coster, Jeffrey T., 1970– . III. United States. Dept. of State. IV. University Publications of America (Firm) V. Title: Confidential U.S. State Department central files. Biafra-Nigeria, 1967–1969. DT515.836 966.905'2—dc22 2006047273 CIP Copyright © 2006 LexisNexis, a division of Reed Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. ISBN 0-88692-756-0. TABLE OF CONTENTS Scope and Content Note......................................................................................... v Source Note............................................................................................................ -

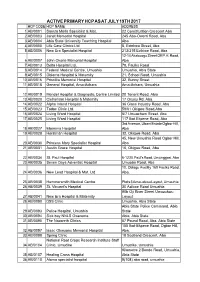

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS at JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat

ACTIVE PRIMARY HCP AS AT JULY 19TH 2017 HCP CODE HCP NAME ADDRESS 1 AB/0001 Sancta Maria Specialist & Mat. 22 Constitutition Crescent Aba 2 AB/0003 Janet Memorial Hospital 245 Aba-Owerri Road, Aba 3 AB/0004 Abia State University Teaching Hospital Aba 4 AB/0005 Life Care Clinics Ltd 8, Ezinkwu Street, Aba 5 AB/0006 New Era Specialist Hospital 213/215 Ezikiwe Road, Aba 12-14 Akabuogu Street Off P.H. Road, 6 AB/0007 John Okorie Memorial Hospital Aba 7 AB/0013 Delta Hospital Ltd. 78, Faulks Road 8 AB/0014 Federal Medical Centre, Umuahia Umuahia, Abia State 9 AB/0015 Obioma Hospital & Maternity 21, School Road, Umuahia 10 AB/0016 Priscillia Memorial Hospital 32, Bunny Street 11 AB/0018 General Hospital, Ama-Achara Ama-Achara, Umuahia 12 AB/0019 Mendel Hospital & Diagnostic Centre Limited 20 Tenant Road, Abia 13 AB/0020 Clehansan Hospital & Maternity 17 Osusu Rd, Aba. 14 AB/0022 Alpha Inland Hospital 36 Glass Industry Road, Aba 15 AB/0023 Todac Clinic Ltd. 59/61 Okigwe Road,Aba 16 AB/0024 Living Word Hospital 5/7 Umuocham Street, Aba 17 AB/0025 Living Word Hospital 117 Ikot Ekpene Road, Aba 3rd Avenue, Ubani Estate Ogbor Hill, 18 AB/0027 Ebemma Hospital Aba 19 AB/0028 Horstman Hospital 32, Okigwe Road, Aba 45, New Umuahia Road Ogbor Hill, 20 AB/0030 Princess Mary Specialist Hospital Aba 21 AB/0031 Austin Grace Hospital 16, Okigwe Road, Aba 22 AB/0034 St. Paul Hospital 6-12 St. Paul's Road, Umunggasi, Aba 23 AB/0035 Seven Days Adventist Hospital Umuoba Road, Aba 10, Oblagu Ave/By 160 Faulks Road, 24 AB/0036 New Lead Hospital & Mat. -

Contending Issues in Party and Electoral Politics and Consequences for Sustainable Democracy in Nigeria: a Historical and Comparative Appraisal

International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science (IJRISS) |Volume II, Issue VIII, August 2018|ISSN 2454-6186 Contending Issues in Party and Electoral Politics and Consequences for Sustainable Democracy in Nigeria: A Historical and Comparative Appraisal Victor E. Ita Department of Political Science, Akwa Ibom State University Obio Akpa Campus, Oruk Anam LGA, Nigeria Abstract:-This article focused on some contending issues in contending issues in party and electoral politics and its Nigeria’s party and electoral politics and its consequences for consequences on sustainable democracy in Nigeria‟s Second sustainable democracy in the country. Based on historical and Republic and its reminisces in the Fourth Republic. comparative analysis, and drawing from the experiences of party and electoral politics in Nigeria’s Second and Fourth Republics, The paper, which is historical and comparative in the paper substantiated the fact that electoral and party politics approach, assumed that Nigeria is faced with the problem of have impacted negatively on the country’s body politics as no conducting free, fair and credible elections. Thus, democracy elections conducted in the country within these epochs have been which is based on the principles of accountability, political adjudged as credible, free and fair. The paper noted factors such equality and representation has not been fully nurtured and as intra-party squabbles, inter-party violence, negative role of entrenched in Nigeria because of selfish party leaders who the security agents during election, the bias nature of electoral commission, godfatherism and money politics are germane to the have been devising means of subverting the democratic problematic nature of party and electoral politics in Nigeria.