UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

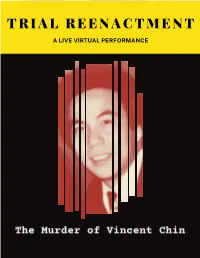

Reenactment Program

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

Man 1Ei'vices, Cal Acauj1 Mracism Toward Confirmed What Americans Ofjapanese Ancestry Have Always Womeb'

• c c November?5 19 3 The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League Chicago Nikkei hear pledges SENATE BILL S 2216 .. Of support from legislators aDCAOO-1be IIbis Dept. cussioos ClIl bow Asian Matsunaga s .... bmits bill 01 iIunum ftjgbtI held a bear Americans are portrayed in fog at Truriian College 00 media, scbools, ami among av. 9 to hear testimony on labor unions. Former JACL on redress to Senate ~otry and other c:mcerns of Midwest ~ Ross lfa.. the state's 250,000 Asians. raoo warDed the department WASHINGTON-Sen.. Spark M. Matsunaga (l)..Hawaii), with Twenty-tive witnEsses ~ that bigotry agaimt Asian 13 colleagues, introduced S 2116 on Nov. 16. The bill would IeDted statements ClIl immi Americans is 00 the rise implement the reammendations of the Commission on War gration ani ref\Jgee pOlicy, natiooally. time Relocation and Internment of Civilians. employment, educatiOn, • JACL Midwest Director In his remarks, Matsunaga stated that, ''The Commission's censing 01 pn!lewjona1a, Bill Y0I!Ihin0 gave aD histori careful review of wartime records, and its extensive hearings, bealtb and ".man 1eI'Vices, cal acauJ1 mracism toward confirmed what Americans ofJapanese ancestry have always womeb'. __, and care of Asians and drew historic known: 1beevacuationofJapanese Americans from the West the t!IcIerIy. parallels to the current at- Coast and their incarceration in what can only be described as Williani Ware. chief of ~ of tension. In ~ ~ntration camps staff for Mayor Harold Wash cl his statement Yosbi- AmericaJrStyle was not justified by mil iDgton, ~ the bearing no saia tbatprejudice and itary necessity, but was the re;ult of racial prejudice, wartime wftb a statement that diS racism "can be as overt as hysteria, and a historic character failure on the part of our crimination against Asian the killing of Vincent Chin in political leaders .• , Americans or any other Detroit or • subUe as the Matsunaga's speech, delivered late last Thursday evening, group, wWld oot be tolerated denial of a job promotion. -

Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990S. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 979 UD 028 599 AUTHOR Chun, Ki-Taek; Zalokar, Nadja TITLE Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; *Asian Americans; *Civil Rights; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Educetion; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Ethnic Discrimination; Higher Education; Immigrants; Minority Groups; *Policy Formation; Public Policy; Racial Bias; *Racial Discrimination; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Commission on Civil Rights ABSTRACT In 1989, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a series of roundtable conferences to learn about the civil rights concerns of Asian Americans within their communities. Using information gathered at these conferences as a point of departure, the Commission undertook this study of the wide-ranging civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Asian American groups considered in the report are persons having origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This report presents the results of that investigation. Evidence is presented that Asian Americans face widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity. The following chapters highlight specificareas: (1) "Introduction," an overview of the problems;(2) "Bigotry and Violence Against Asian Americans"; (3) "Police Community Relations"; (4) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Asian American Immigrant Children in Primary and Secondary Schools";(5) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Higher Education"; (6) "Employment Discrimination";(7) "Other Civil Rights Issues Confronting Asian AmericansH; and (8) "Conclusions and Recommendations." More than 40 recommendations for legislative, programmatic, and administrative efforts are made. -

Toward an Asian American Legal Scholarship: Critical Race Theory, Post-Structuralism, and Narrative Space

Toward an Asian American Legal Scholarship: Critical Race Theory, Post-Structuralism, and Narrative Space Robert S. Chang TABLE OF CONTENTS Prelude ........................................ 1243 Introduction: Mapping the Terrain ............................. 1247 I. The Need for an Asian American Legal Scholarship ........ 1251 A. That Was Then, This Is Now: Variations on a Theme .. 1251 1. Violence Against Asian Americans ................. 1252 2. Nativistic Racism .................................. 1255 B. The Model Minority Myth ............................. 1258 C. The Inadequacy of the Current Racial Paradigm ........ 1265 1. Traditional Civil Rights Work ...................... 1265 2. Critical Race Scholarships .......................... 1266 II. Narrative Space ........................................... 1268 A. Perspective Matters ................................... 1272 B. Resistance to Narrative ................................ 1273 C. Epistemological Strategies .............................. 1278 1. Arguing in the Rational/Empirical Mode ........... 1279 2. Post-Structuralism and the Narrative Turn .......... 1284 III. The Asian American Experience: A Narrative Account of Exclusion and Marginalization ............................. 1286 A. Exclusion from Legal and Political Participation ........ 1289 1. Immigration and Naturalization .................... 1289 2. Disfranchisement .................................. 1300 B. Speaking Our Oppression into (and out of) Existence ... 1303 1. The Japanese American Internment and Redress -

Photography, Performativity, and Immigration Re-Imagined in the Self-Portraits of Tseng Kwong Chi, Nikki S

Upending the Melting Pot: Photography, Performativity, and Immigration Re-Imagined in the Self-Portraits of Tseng Kwong Chi, Nikki S. Lee, and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew By Copyright 2016 Ellen Cordero Raimond Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ________________________________ Chairperson John Pultz ________________________________ David C. Cateforis ________________________________ Sherry D. Fowler ________________________________ Kelly H. Chong ________________________________ Ludwin E. Molina Date Defended: 28 March 2016 The Dissertation Committee for Ellen Cordero Raimond certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Upending the Melting Pot: Photography, Performativity, and Immigration Re-Imagined in the Self-Portraits of Tseng Kwong Chi, Nikki S. Lee, and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew ________________________________ Chairperson John Pultz Date approved: 28 March 2016 ii Abstract Tseng Kwong Chi, Nikki S. Lee, and Annu Palakunnathu Matthew each employ our associations with photography, performativity, and self-portraiture to compel us to re-examine our views of immigrants and immigration and bring them up-to-date. Originally created with predominantly white European newcomers in mind, traditional assimilative narratives have little in common with the experience of immigrants of color for whom “blending in” with “white mainstream America” is not an option. -

"Forum: Understanding the Rising Anti-Asian Violence" Presentation

3/26/2021 Forum: Understanding the Rising Anti-Asian Violence Increasing Awareness and Promoting Solidarity Lei Guo, Xuan Jiang, Maria Elena Villar Anti-Asian attacks on the rise: Did it all come from a vacuum? There is a long history anti-Asian discrimination, History is often neglected/forgotten. Racism is opportunistic: It comes in many forms; Behind it, there is always ignorance, prejudice and fear. 1 3/26/2021 The First Major Wave • The Gold Rush (1848-1852) • The transcontinental railroad: • 90% of the workers are Chinese • Up to 20,000 in total • 30%-50% lower pay • Their contributions largely ignored Up to 1,200 deaths Railroad officials and employees celebrate the completion of the • first railroad transcontinental link in Prementory, Utah, on May 10, 1869. (Andrew Russell/Union Pacific/AP Photo) • But: Where are the Chinese? • Were hired Chinese laborers allowed to immigrate? Resource: The Chinese Railroad Workers in North America Project @ Stanford University First Federal Immigration law: The Chinese Exclusion Act • Kamala Harris questioning supreme court nominee Kavanaugh in 2018: • “Should the 1889 ruling be overturned?”: Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889), better known as the Chinese Exclusion Case • Why are the Chinese excluded? (1882-1943) • Dirty/Unsanitary/Stealing jobs 2 3/26/2021 Constitutional Amendment 14: Birthright Citizenship • What about the Chinese born in U.S.A? • United States v. Wong Kim Ark, 169 U.S. 649 (1898) • Born in San Francisco, United States. • Denied entry upon visiting China -

AAPI National Historic Landmarks Theme Study Essay 13

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior A National Historic Landmarks Theme Study ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER ISLANDER AMERICAN PACIFIC ASIAN Finding a Path Forward ASIAN AMERICAN PACIFIC ISLANDER NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY LANDMARKS HISTORIC NATIONAL NATIONAL HISTORIC LANDMARKS THEME STUDY Edited by Franklin Odo Use of ISBN This is the official U.S. Government edition of this publication and is herein identified to certify its authenticity. Use of 978-0-692-92584-3 is for the U.S. Government Publishing Office editions only. The Superintendent of Documents of the U.S. Government Publishing Office requests that any reprinted edition clearly be labeled a copy of the authentic work with a new ISBN. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Odo, Franklin, editor. | National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.), issuing body. | United States. National Park Service. Title: Finding a Path Forward, Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study / edited by Franklin Odo. Other titles: Asian American and Pacific Islander National Historic Landmarks theme study | National historic landmark theme study. Description: Washington, D.C. : National Historic Landmarks Program, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, 2017. | Series: A National Historic Landmarks theme study | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017045212| ISBN 9780692925843 | ISBN 0692925848 Subjects: LCSH: National Historic Landmarks Program (U.S.) | Asian Americans--History. | Pacific Islander Americans--History. | United States--History. Classification: LCC E184.A75 F46 2017 | DDC 973/.0495--dc23 | SUDOC I 29.117:AS 4 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017045212 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. -

The Righteous Fists of Harmony: Asian American Revolutionaries in the Radical Minority and Third World Liberation Movements, 1968-1978

The Righteous Fists of Harmony: Asian American Revolutionaries in the Radical Minority and Third World Liberation Movements, 1968-1978 By Angela L. Zhao Presented to the Department of History in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the BA Degree The University of Chicago April 6, 2018 Abstract In the late 1960s, a group comprised mostly of young second-generation Asian Americans began an attempt to start a socialist political revolution alongside other radical groups of color to uplift their communities from racial discrimination and poverty and critique the capitalist and imperialist structures that caused oppression. The group became the first national Asian American political organization and called themselves I Wor Kuen (IWK), meaning The Righteous Fists of Harmony. This thesis traces the origins and growth of IWK between 1968 and 1978 to show how it radicalized the Asian American political identity by connecting with the activism of the Black Panthers and the Puerto Rican Young Lords, as well as with revolutionary uprisings particularly in Asia but throughout the “Third World.” Predominantly featuring oral histories, I argue that I Wor Kuen played a fundamental role in shaping the concept of Asian American by turning it into an political identity that used racial solidarity and global revolutionary inspiration to resist assimilation and contest racial, class-based, and gendered systems of oppression. Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the support of the Asian Americans I spoke with who were involved in I Wor Kuen and the larger radical movement of the 1960s and 1970s; their voices are the foundation of my narrative. -

Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National Imagination

Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1997 Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National Imagination Robert S. Chang Keith Aoki Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty Part of the Immigration Law Commons, and the Law and Race Commons Recommended Citation Robert S. Chang and Keith Aoki, Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National Imagination, 85 CALIF. L. REV. 1395 (1997). https://digitalcommons.law.seattleu.edu/faculty/479 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Seattle University School of Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. -Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National Imagination Robert S. Changt & Keith Aokit In this Article, Professors Chang and Aoki examine the relationship between the immigrant and the nation in the complicated racial terrain known as the United States. Special attention is paid to the border which contains and configures the local, the national and the interna- tional. They criticize the contradictory impulse that has led to borders becoming increasingly porous to the flows of information, goods and capital while simultaneously constricting when it comes to the movement of certain persons, particularly those of Asian and Latinalo ancestry. The authors examine Monterey Park, California, as one site where there has been a large influx of capital, information, and persons. Centering the immigrant in their analysis allows them to observe the interaction of Copyright © 1997 California Law Review, Inc. -

The Assimilation of Sushi, the Internment of Japanese Americans, and the Killing of Vincent Chin, a Personal Essay

Scattered: The Assimilation of Sushi, the Internment of Japanese Americans, and the Killing of Vincent Chin, A Personal Essay Frank H. Wu† ABSTRACT In a personal Essay, Frank H. Wu discusses the acceptance of sushi in America as a means of analyzing the acceptance of Japanese Americans, before, during, and after World War II. The murder of Vincent Chin in Detroit in 1982 is used as a defining moment for Asian Americans, explaining the shared experiences of people perceived as “perpetual foreigners.” ABSTRACT ......................................................................................... 109 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 109 I.“BORN IN THE U.S.A.” .................................................................... 114 II.DISCOVERING CHIRASHI ............................................................... 117 III.RECOVERING THE INTERNMENT .................................................. 120 CONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 126 INTRODUCTION Coming of age as the Japanese economy was coming to be envied for its rise, I started eating sushi when Americans were just willing, curiosity overcoming disgust inexorably, to sample it, chopsticks and all.1 The late DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38KD1QK94 †. William L. Prosser Distinguished Professor, University of California Hastings College of the Law. I thank Carol Izumi, David Levine, and Reuel Schiller, for comments on drafts. Hilary Hardcastle, librarian at UC Hastings, provided ample assistance. 1. Regarding the arrival of sushi in America, see generally TREVOR CORSON, THE STORY OF SUSHI: AN UNLIKELY SAGA OF RAW FISH AND RICE (2008). See also CHOP SUEY AND SUSHI FROM SEA TO SHINING SEA: CHINESE AND JAPANESE RESTAURANTS IN THE UNITED STATES (Bruce Makoto Arnold et al. eds., 2018); JONAS HOUSE, SUSHI IN THE UNITED STATES, 1945–1970, 26 FOOD & FOODWAYS 40 (2018). In 1975, Gourmet magazine published a series of articles on Japanese cuisine, which were an important introduction. -

The Muddled History of Anti-Asian Violence

Cultural Comment The Muddled History of Anti-Asian Violence By Hua Hsu February 28, 2021 It’s difficult to describe anti-Asian racism when society lacks a coherent historical account of what it actually looks like. Photograph from SOPA / Alamy n the evening of April 28, 1997, Kuan Chung Kao, a thirty-three-year-old Taiwan-born engineer, went to the Cotati Yacht O Club near Rohnert Park, a quiet suburb in Sonoma County, California, where he lived with his wife and three children. Kao went to the bar a couple of times a week for an after-work glass of red wine; on this evening, he was celebrating a new job. According to a bartender working that night, Kao got in an argument with a customer, who mistook him for Japanese. “You all look alike to me,” the man said. Tensions simmered, and, later in the evening, the man returned to needle Kao some more. “I’m sick and tired of being put down because I’m Chinese,” Kao shouted back. “If you want to challenge me, now’s the time to do it.” An altercation followed, and someone called the police. When they arrived, the bartender, who later described Kao as a “caring and friendly” patron, helped defuse the situation and assured them that causing a ruckus was out of Kao’s character. He was sent home in a cab. Still livid, Kao shouted outside his house late into the night, alarming his neighbors, who placed about a dozen calls to 911. When two officers arrived, Kao was standing in his driveway, holding a stick. -

Hate\222S Harms Persist 25 Years After Raleigh Murder | Other Views | Newsobserver.Com

Hate’s harms persist 25 years after Raleigh murder | Other Views | News... http://www.newsobserver.com/2014/07/26/4030242/hates-harms-persist-... NewsObserver.com Previous Story Next Story Point of view Hate’s harms persist 25 years after Raleigh murder By Andrew Chin July 26, 2014 Facebook Twitter Google Plus Reddit E-mail Print RON CHAPPLE STOCK — Getty Images/Ron Chapple Studios A racially motivated murder in Raleigh 25 years ago led to the first federal conviction of a person for hate crimes against an Asian-American. On the night of Friday, July 28, 1989, Chinese-American restaurant worker Jim Loo, 24, of Cary and six of his 1 of 3 7/28/2014 1:35 AM Hate’s harms persist 25 years after Raleigh murder | Other Views | News... http://www.newsobserver.com/2014/07/26/4030242/hates-harms-persist-... friends met to play pool at the Cue ‘N’ Spirits on Atlantic Avenue in Raleigh. Lloyd and Robert Piche, two brothers drinking at the bar, confronted the group, referring to a brother who had died in the Vietnam War, making threatening gestures and challenging the men to fight, using such names as “slanty-eyed gooks,” “black pajamas” and “rice eaters.” Lloyd Piche, who made most of the racial remarks, also made kung fu gestures, pretended to fire a machine gun at the group and tried to recruit another white bar patron into the dispute. Throughout the harassment, Loo’s group remained quiet and tried to ignore the Piches. The Piches left the bar and waited in the parking lot.