Centering the Immigrant in the Inter/National Imagination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

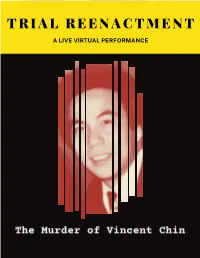

Reenactment Program

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

From TINSELTOWN to BORDERTOWN

From TINSELTOWN to BORDERTOWN DeleytoDesign typesetindex.indd 1 2/20/17 12:19 PM Celestino Deleyto Contemporary Approaches to Film and Media Series A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu. General Editor Barry Keith Grant Brock University Advisory Editors Robert J. Burgoyne University of St. Andrews Caren J. Deming From TINSELTOWN University of Arizona LOS ANGELES ON FILM Patricia B. Erens to BORDERTOWN School of the Art Institute of Chicago Peter X. Feng University of Delaware Lucy Fischer University of Pittsburgh WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Frances Gateward DETROIT California State University, Northridge Tom Gunning University of Chicago Thomas Leitch University of Delaware Walter Metz Southern Illinois University DeleytoDesign typesetindex.indd 2-1 2/20/17 12:19 PM Celestino Deleyto Contemporary Approaches to Film and Media Series A complete listing of the books in this series can be found online at wsupress.wayne.edu. General Editor Barry Keith Grant Brock University Advisory Editors Robert J. Burgoyne University of St. Andrews Caren J. Deming From TINSELTOWN University of Arizona LOS ANGELES ON FILM Patricia B. Erens to BORDERTOWN School of the Art Institute of Chicago Peter X. Feng University of Delaware Lucy Fischer University of Pittsburgh WAYNE STATE UNIVERSITY PRESS Frances Gateward DETROIT California State University, Northridge Tom Gunning University of Chicago Thomas Leitch University of Delaware Walter Metz Southern Illinois University DeleytoDesign typesetindex.indd 2-1 2/20/17 12:19 PM © 2016 by Wayne State University Press, Detroit, Michigan 48201. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without formal permission. -

In Los Angeles, the Ghosts of Rodney King and Watts Rise Again Los Angeles Has Been One of Americaʼs Reference Points for Racial Unrest

7/1/2020 Protests in L.A.: The Ghosts of Rodney King and Watts Rise Again - The New York Times https://nyti.ms/2XWu0Rp In Los Angeles, the Ghosts of Rodney King and Watts Rise Again Los Angeles has been one of Americaʼs reference points for racial unrest. This time protesters are bringing their anger to the people they say need to hear it most: the white and wealthy. By Tim Arango June 3, 2020 LOS ANGELES — Patrisse Cullors was 8 in 1992, when Los Angeles erupted in riots after four police officers were acquitted of assault for the beating of Rodney King, which occurred outside a San Fernando Valley apartment building not far from where Ms. Cullors grew up. “I was scared as hell,” she recalled. “As children, when we would see the police, our parents would tell us, ʻBehave, be quiet, don’t say anything.’ There was such fear of law enforcement in this city.” With America seized by racial unrest, as protests convulse cities from coast to coast after the death of George Floyd, Los Angeles is on fire again. As peaceful protests in the city turned violent over the past few days, with images of looting and burning buildings captured by news helicopters shown late into the night, Ms. Cullors, like many Angelenos, was pulled back to the trauma of 1992. The parallels are easy to see: looting and destruction, fueled by anger over police abuses; shopkeepers, with long guns, protecting their businesses. The differences, though, between 1992 and now, are stark. This time, the faces of the protesters are more diverse — black, white, Latino, Asian; there has been little if any racially motivated violence among Angelenos; and the geography of the chaos is very different, with protesters bringing their message to Los Angeles’ largely white and rich Westside. -

Spartan Daily City Editor Tony Marck Was Jumped, Daily Sta Ff Report Struck and His Backpack Was Stolen

RIOTS ROCK SAN JOSE People react with shock, anger to King verdict tPvo4 PAR DAILY Ito Vol. 98, No. 64 Published for San lose State University since 1934 Friday, May 1, 1992 Protest erupts into violence MYCIO I. Sanchez -- - Daily staff phot,,,, Protestors were divided as some called for violence (top) and others begged for a peaceful demonstration (bottom) Wednesday night against the verdict of the Rodney King beating trial Protests and rallies take over campus, downtown as result of discontent Pushing as a unit, the racially mixed but predominantly Riot breeds violence black and Ilispanic crowd, forged off down San Salvador. Rallies split between peace, destruction Spartan Daily City Editor Tony Marck was jumped, Daily sta ff report struck and his backpack was stolen. A flash was yanked Daily staff report RELATED SToRiES Swarming though SJSII and San Jose's downtown from Spartan Daily photographer Scott Sady. streets, crowds of stinkms and local residents stung the city Guy Wallrath was watching television in his Joe West As of 10:40 p.m. Thursday night, downtown San Jose Opinions on the verdict Page 1 with anger and violence Wednesday night. room when someone came in and said, "Man, if you're was seeing a repeat performance of the night before Thursday's press conference, police And they left scars. white, don't go downstairs." magnified. respond to the violence Page 3 What started as a mild campus protest against the The crowd moved like molten lava, splitting near the Rioting, window breaking, looting, fires and arrests Timeline, map and photographs of Wednes- acquittal of four Los Angeles police officers in the Rodney Dining Commons. -

Media Interaction with the Public in Emergency Situations: Four Case Studies

MEDIA INTERACTION WITH THE PUBLIC IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS: FOUR CASE STUDIES A Report Prepared under an Interagency Agreement by the Federal Research Division, Library of Congress August 1999 Authors: LaVerle Berry Amanda Jones Terence Powers Project Manager: Andrea M. Savada Federal Research Division Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540–4840 Tel: 202–707–3900 Fax: 202–707–3920 E-Mail: [email protected] Homepage:http://www.loc.gov/rr/frd/ PREFACE The following report provides an analysis of media coverage of four major emergency situations in the United States and the impact of that coverage on the public. The situations analyzed are the Three Mile Island nuclear accident (1979), the Los Angeles riots (1992), the World Trade Center bombing (1993), and the Oklahoma City bombing (1995). Each study consists of a chronology of events followed by a discussion of the interaction of the media and the public in that particular situation. Emphasis is upon the initial hours or days of each event. Print and television coverage was analyzed in each study; radio coverage was analyzed in one instance. The conclusion discusses several themes that emerge from a comparison of the role of the media in these emergencies. Sources consulted appear in the bibliography at the end of the report. i TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ................................................................... i INTRODUCTION: THE MEDIA IN EMERGENCY SITUATIONS .................... iv THE THREE MILE ISLAND NUCLEAR ACCIDENT, 1979 ..........................1 Chronology of Events, March -

The Rodney King Beating Verdicts Hiroshi Fukurai, Richard Krooth, and Edgar W

111.e Lo, A~~~ 'R1trl-S ':, Gz~~b~<S :fvv ~ U~--b~ 'fV}v~ (Hat.- k Baldo5~qv-"'_, e.d.) 1 /t9lf 4 The Rodney King Beating Verdicts Hiroshi Fukurai, Richard Krooth, and Edgar W. Butler As a landmark in the recent history of law enforcement and jury trials, the Rodney King beating trials are historically comparable to the 1931 Scottsboro case (Norris v. Alabama, 294 U.S. 587, 1935) or the 1968 Huey Newton case (Newton v. California, 8 Cal App 3d 359, 87 Cal Rptr 394, 1970). The King beating cases are also similar to Florida trials that led to three urban riots and rebellion during 1980s in Miami, Florida in which police officers were acquitted of criminal charges in the death of three blacks: Arthur McDuffie in 1980, NeveU Johnson in 1982, and Clement Anthony Lloyd in 1989. The 1980 McDuffie riots, for instance, resulted in eighteen deaths and eighty million dollars in property damage (Barry v. Garcia, 573 So.2d 932 933, 1991). An all white jury acquitted police officers of all criminal charges in the face of compelling evidence against them, including the testimony of the chief medical officer who said that McDuffie's head injuries were the worst he had seen in 3,600 autopsies (Crewdson, 1980). The verdict triggered violence because it symbolized the continuation of racial inequities in the criminal justice and court system. Similarly, in the King beating trial and jury verdict which was rightly called "sickening" by then-President Bush and condemned by all segments of society, the King embroglio also provides an opportunity for evaluation and reform of police procedures, law enforcement structures, and jury trials. -

Setting the Record Straight

Video 1 Setting the Record Straight: Citizens’ First Amendment Right to Video Police in Public Video 2 Abstract There is an alarming trend in the United States of citizens being arrested for videotaping police officers in public. Cell phones with video capabilities are ubiquitous and people are using their phones to document the behavior of police officers in a public place. The goal of this paper is to study the trend of citizen arrests currently in the news and recommend solutions to the problem of encroachment upon First Amendment rights through case law. Video 3 Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances .1 – The First Amendment Introduction One of the five guarantees stated in the First Amendment is that citizens have a right to monitor their government. Currently there is a trend in the United States of police officers arresting citizens who are monitoring their actions using video in a public place. With the evolution of technology, citizens have become amateur reporters. If a person owns a smart phone, he has the capacity to videotape what happens in front of him. If he has a YouTube account, blog, or Facebook page, he can upload a video in a matter of seconds, therefore broadcasting his content on a public platform. Videos have proven to be beneficial to the justice system. An historic case of police brutality may have never seen the light of day if it were not for one of the nation’s first so-called citizen journalists. -

The Rodney King Riots

1 Framing Perspective: How Video has Shaped Public Opinion An Honors Thesis (HONR 499) by Jason W. Puhr Thesis Advisor Terry Heifetz Signed Ball State University Muncie, Indiana May 2015 Expected Date of Graduation May 2,2015 q,pCo) J U nd Ci d h c- J-zc' -r 2 L Abstract Video cameras have come a long way since Charles Ginsburg created the first practical videotape recorder in 1951. Today millions ofAmericans live with cameras in their pockets. The growth of video has changed the communication industry into one that is shown rather than described. Video has created a direct window into the world, one that cannot be achieved equally by other communication methods and one that reaches into the hearts of its viewers. This window has shaped public opinion, as we know it, bringing images directly into the homes of millions from who knows how far away. In this thesis, I will examine major moments in U.S. history that influenced public opinion. I will explain the event itself, what was captured on camera, the effects and aftermath of the video and how the world may be different without the coverage. Acknowledgements I want to thank all the members of the Ball State faculty and staff who helped me to come up with the idea for this project, particularly Terry Heifetz and Stephanie Wiechmann. I also want to thank Terry for working and editing this project with me over the last ten months. I am very grateful to Indiana Public Radio as well, for providing a quiet and productive workspace. -

Man 1Ei'vices, Cal Acauj1 Mracism Toward Confirmed What Americans Ofjapanese Ancestry Have Always Womeb'

• c c November?5 19 3 The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League Chicago Nikkei hear pledges SENATE BILL S 2216 .. Of support from legislators aDCAOO-1be IIbis Dept. cussioos ClIl bow Asian Matsunaga s .... bmits bill 01 iIunum ftjgbtI held a bear Americans are portrayed in fog at Truriian College 00 media, scbools, ami among av. 9 to hear testimony on labor unions. Former JACL on redress to Senate ~otry and other c:mcerns of Midwest ~ Ross lfa.. the state's 250,000 Asians. raoo warDed the department WASHINGTON-Sen.. Spark M. Matsunaga (l)..Hawaii), with Twenty-tive witnEsses ~ that bigotry agaimt Asian 13 colleagues, introduced S 2116 on Nov. 16. The bill would IeDted statements ClIl immi Americans is 00 the rise implement the reammendations of the Commission on War gration ani ref\Jgee pOlicy, natiooally. time Relocation and Internment of Civilians. employment, educatiOn, • JACL Midwest Director In his remarks, Matsunaga stated that, ''The Commission's censing 01 pn!lewjona1a, Bill Y0I!Ihin0 gave aD histori careful review of wartime records, and its extensive hearings, bealtb and ".man 1eI'Vices, cal acauJ1 mracism toward confirmed what Americans ofJapanese ancestry have always womeb'. __, and care of Asians and drew historic known: 1beevacuationofJapanese Americans from the West the t!IcIerIy. parallels to the current at- Coast and their incarceration in what can only be described as Williani Ware. chief of ~ of tension. In ~ ~ntration camps staff for Mayor Harold Wash cl his statement Yosbi- AmericaJrStyle was not justified by mil iDgton, ~ the bearing no saia tbatprejudice and itary necessity, but was the re;ult of racial prejudice, wartime wftb a statement that diS racism "can be as overt as hysteria, and a historic character failure on the part of our crimination against Asian the killing of Vincent Chin in political leaders .• , Americans or any other Detroit or • subUe as the Matsunaga's speech, delivered late last Thursday evening, group, wWld oot be tolerated denial of a job promotion. -

Finding Aid to the Historymakers ® Video Oral History with Joseph Dyer

Finding Aid to The HistoryMakers ® Video Oral History with Joseph Dyer Overview of the Collection Repository: The HistoryMakers®1900 S. Michigan Avenue Chicago, Illinois 60616 [email protected] www.thehistorymakers.com Creator: Dyer, Joseph, 1934- Title: The HistoryMakers® Video Oral History Interview with Joseph Dyer, Dates: April 23, 2004 Bulk Dates: 2004 Physical 7 Betacame SP videocasettes (3:34:48). Description: Abstract: Broadcast executive and television reporter Joseph Dyer (1934 - 2011 ) was the first African American to work as a television reporter and executive in the Los Angeles community. He played a critical role in covering the 1965 riots, interviewing key community leaders. At the time of his retirement, Dyer had spent more than thirty years with CBS-2. Dyer was interviewed by The HistoryMakers® on April 23, 2004, in Los Angeles, California. This collection is comprised of the original video footage of the interview. Identification: A2004_047 Language: The interview and records are in English. Biographical Note by The HistoryMakers® The first African American to work as a television reporter and executive in the Los Angeles community, Joseph Dyer was born in Gilbert, Louisiana, on September 24, 1934. The son of sharecroppers, Dyer’s father passed away while he was still a child, and by the age of ten, Dyer was picking cotton in the fields with his deaf mother. After graduating from high school in 1953, he attended Xavier University for one year on a football scholarship before transferring to Xavier University for one year on a football scholarship before transferring to Grambling State University, where he earned his B.A. -

Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990S. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 979 UD 028 599 AUTHOR Chun, Ki-Taek; Zalokar, Nadja TITLE Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; *Asian Americans; *Civil Rights; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Educetion; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Ethnic Discrimination; Higher Education; Immigrants; Minority Groups; *Policy Formation; Public Policy; Racial Bias; *Racial Discrimination; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Commission on Civil Rights ABSTRACT In 1989, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a series of roundtable conferences to learn about the civil rights concerns of Asian Americans within their communities. Using information gathered at these conferences as a point of departure, the Commission undertook this study of the wide-ranging civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Asian American groups considered in the report are persons having origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This report presents the results of that investigation. Evidence is presented that Asian Americans face widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity. The following chapters highlight specificareas: (1) "Introduction," an overview of the problems;(2) "Bigotry and Violence Against Asian Americans"; (3) "Police Community Relations"; (4) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Asian American Immigrant Children in Primary and Secondary Schools";(5) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Higher Education"; (6) "Employment Discrimination";(7) "Other Civil Rights Issues Confronting Asian AmericansH; and (8) "Conclusions and Recommendations." More than 40 recommendations for legislative, programmatic, and administrative efforts are made. -

Dramaturgy Rodney King Case Korean-Black Riots

Dramaturgy Demography: 44% Hispanic, 42% African-American, 9% white, 2% other Location: Southern LA County, near Beverly Hills Rodney King Case Time Span: Incident March 3, 1991. Cops Acquitted April 29, 1992. The Case: Three Caucasian and one Latino Cops pull over Rodney King during a traffic stop and violently beat him unconscious on the ground. Third party films part of scene. The Trial: Prosecution charges officers and sergeant for “assault by force likely to produce great bodily injury… under color of authority” and filing false police reports. King accused of being under PCP drug. Trial takes place far away from LA county (where crime occurred, where blacks and Hispanics make up majority pop.) and in Simi Valley, Ventura County (a wealthy suburban neighborhood, % blacks much less, % law enforcement much higher). Jury from all economic backgrounds from San Fernando Valley but still made up of 10 whites, 1 Latino, 1 Asian. Verdict undecided so cops acquitted. King eventually undergoes several surgical operations, do not recover, gets $3.8 mil from the LAPD, goes bankrupt, and now lives in a drug rehab center. The Response: Public outrage and disbelief Æ 1992 LA Riots. Bush supports verdict and attempts to ignore public response. Korean-Black Riots Time Span: April 29, 1992 (day cops acquitted) Æ several days The Major Causes: Rodney King case cops acquitted. Latino and Korean population inflation, replacing many black workers. High unemployment and police abuse. Korean store owner indicted very lightly for shooting Latasha Harlings, and black teenage girl who tried to steal a $1.79 bottle of juice.