AAPI National Historic Landmarks Theme Study Essay 13

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982

[ARTICLES] "Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb": Title Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 Author(s) UCHINO, Crystal Citation 社会システム研究 (2019), 22: 103-120 Issue Date 2019-03-20 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/241029 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb” 103 “Born Under the Shadow of the A-bomb”: Atomic Bomb Memory and the Japanese/Asian American Radical Imagination, 1968-1982 UCHINO Crystal Introduction This article explores the significance of the atomic bomb in the political imaginaries of Asian American activists who participated in the Asian American movement (AAM) in the 1960s and 1970s. Through an examination of articles printed in a variety of publications such as the Gidra, public speeches, and conference summaries, it looks at how the critical memory of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki acted as a unifying device of pan-Asian radical expression. In the global anti-colonial moment, Asian American activists identified themselves with the metaphorical monsters that had borne the violence of U.S. nuclear arms. In doing so, they expressed their commitment to a radical vision of social justice in solidarity with, and as a part of, the groundswell of domestic and international social movements at that time. This was in stark contrast to the image of the Asian American “model minority.” Against the view that antinuclear activism faded into apathy in the 1970s because other social issues such as the Vietnam War and black civil rights were given priority, this article echoes the work of scholars who have emphasized how nuclear issues were an important component of these rising movements. -

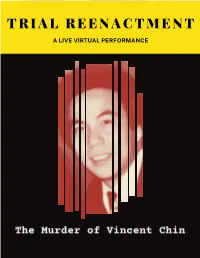

Reenactment Program

T R I A L R E E N A C T M E N T A LIVE VIRTUAL PERFORMANCE The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida WITH ITS COHOSTS The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of Tampa Bay The Greater Orlando Asian American Bar Association The Jacksonville Asian American Bar Association PRESENT THE MURDER OF VINCENT CHIN ORIGINAL SCRIPT BY THE ASIAN AMERICAN BAR ASSOCIATION OF NEW YORK VISUALS BY JURYGROUP TECHNOLOGY SUPPORT BY GREENBERG TRAURIG, PA WITH MARIA AGUILA ONCHANTHO AM VANESSA L. CHEN BENJAMIN W. DOWERS ZARRA ELIAS TIMOTHY FERGUSON JACQUELINE GARDNER ALLYN GINNS AYERS E.J. HUBBS JAY KIM GREG MAASWINKEL MELISSA LEE MAZZITELLI GUY KAMEALOHA NOA ALICE SUM AND THE HONORABLE JEANETTE BIGNEY THE HONORABLE HOPE THAI CANNON THE HONORABLE ANURAAG SINGHAL ARTISTIC DIRECTION BY DIRECTED BY PRODUCED BY ALLYN GINNS AYERS BERNICE LEE SANDY CHIU ABOUT APABA SOUTH FLORIDA The Asian Pacific American Bar Association of South Florida (APABA) is a non-profit, voluntary bar organization of attorneys in Miami-Dade, Broward, and Palm Beach counties who support APABA’s objectives and are dedicated to ensuring that minority communities are effectively represented in South Florida. APABA of South Florida is an affiliate of the National Asian Pacific American Bar Association (“NAPABA”). All members of APABA are also members of NAPABA. APABA’s goals and objectives coincide with those of NAPABA, including working towards civil rights reform, combating anti-immigrant agendas and hate crimes, increasing diversity in federal, state, and local government, and promoting professional development. The overriding mission of APABA is to combat discrimination against all minorities and to promote diversity in the legal profession. -

Asian American College Student Activism and Social Justice in Midwest Contexts

The Midwest regional context complicates Asian American college student activism and social justice efforts so understanding these dynamics can equip higher education practitioners to better support these students. Asian American College Student Activism and Social Justice in Midwest Contexts Jeffrey Grim, Nue Lee, Samuel Museus, Vanessa Na, Marie P. Ting1 Systemic oppression shapes the experiences of Asian Americans. Globally, imperialism, colonialism, and struggles among major economic powers have led to systemic violence toward, and significant challenges for, Asian American communities (Aguirre & Lio, 2008). Nationally, systemic racism—as well as other systems of oppression such as neoliberalism, poverty, and heteropatriarchy—continue to cause challenges for Asian America and the diverse communities within it. And, on college campuses, these forces have an impact on the everyday lives of Asian American faculty, staff, and students (Museus & Park, 2012). Many Asian Americans engage in efforts to resist systemic forms of oppression and advance equity through political activism. College and university leaders often view such resistance as a burden. However, political activism is a fundamental democratic process (Kezar, 2010; Slocum & Rhoades, 2009. Therefore, we believe that institutions that claim and seek to cultivate students‘ skills to productively engage and lead in a democratic society should encourage student activism and understand how to collaborate with activists to improve conditions on their campuses and in their surrounding communities. In this chapter, we provide insight into the factors that shape Asian American activism in the Midwest. In the following sections, we provide critical context necessary to understand the experiences of Asian American activists in postsecondary education in the Midwest region. -

Man 1Ei'vices, Cal Acauj1 Mracism Toward Confirmed What Americans Ofjapanese Ancestry Have Always Womeb'

• c c November?5 19 3 The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League Chicago Nikkei hear pledges SENATE BILL S 2216 .. Of support from legislators aDCAOO-1be IIbis Dept. cussioos ClIl bow Asian Matsunaga s .... bmits bill 01 iIunum ftjgbtI held a bear Americans are portrayed in fog at Truriian College 00 media, scbools, ami among av. 9 to hear testimony on labor unions. Former JACL on redress to Senate ~otry and other c:mcerns of Midwest ~ Ross lfa.. the state's 250,000 Asians. raoo warDed the department WASHINGTON-Sen.. Spark M. Matsunaga (l)..Hawaii), with Twenty-tive witnEsses ~ that bigotry agaimt Asian 13 colleagues, introduced S 2116 on Nov. 16. The bill would IeDted statements ClIl immi Americans is 00 the rise implement the reammendations of the Commission on War gration ani ref\Jgee pOlicy, natiooally. time Relocation and Internment of Civilians. employment, educatiOn, • JACL Midwest Director In his remarks, Matsunaga stated that, ''The Commission's censing 01 pn!lewjona1a, Bill Y0I!Ihin0 gave aD histori careful review of wartime records, and its extensive hearings, bealtb and ".man 1eI'Vices, cal acauJ1 mracism toward confirmed what Americans ofJapanese ancestry have always womeb'. __, and care of Asians and drew historic known: 1beevacuationofJapanese Americans from the West the t!IcIerIy. parallels to the current at- Coast and their incarceration in what can only be described as Williani Ware. chief of ~ of tension. In ~ ~ntration camps staff for Mayor Harold Wash cl his statement Yosbi- AmericaJrStyle was not justified by mil iDgton, ~ the bearing no saia tbatprejudice and itary necessity, but was the re;ult of racial prejudice, wartime wftb a statement that diS racism "can be as overt as hysteria, and a historic character failure on the part of our crimination against Asian the killing of Vincent Chin in political leaders .• , Americans or any other Detroit or • subUe as the Matsunaga's speech, delivered late last Thursday evening, group, wWld oot be tolerated denial of a job promotion. -

Toward a Queer Diasporic Asian America

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2017 Cruising Borders, Unsettling Identities: Toward a Queer Diasporic Asian America Wen Liu The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2017 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Running head: CRUISING BORDERS UNSETTLING IDENTITIES CRUISING BORDERS, UNSETTLING IDENTITIES TOWARD A QUEER DIASPORIC ASIAN AMERICA by WEN LIU A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 CRUISING BORDERS UNSETTLING IDENTITIES © 2017 WEN LIU All Rights Reserved ii CRUISING BORDERS UNSETTLING IDENTITIES Cruising Borders, Unsettling Identities: Toward A Queer Diasporic Asian America by Wen Liu This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Psychology in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. ___________________ _____________________________________________ Date Michelle Fine Chair of Examination Committee ___________________ _____________________________________________ Date Richard Bodnar Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Sunil Bhatia Celina Su THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii CRUISING BORDERS UNSETTLING IDENTITIES ABSTRACT Cruising Borders, Unsettling Identities: Toward A Queer Diasporic Asian America by Wen Liu Advisor: Michelle Fine In this dissertation, I challenge the dominant conceptualization of Asian Americanness as a biological and cultural population and a cohesive racial category. -

Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990S. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 979 UD 028 599 AUTHOR Chun, Ki-Taek; Zalokar, Nadja TITLE Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; *Asian Americans; *Civil Rights; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Educetion; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Ethnic Discrimination; Higher Education; Immigrants; Minority Groups; *Policy Formation; Public Policy; Racial Bias; *Racial Discrimination; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Commission on Civil Rights ABSTRACT In 1989, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a series of roundtable conferences to learn about the civil rights concerns of Asian Americans within their communities. Using information gathered at these conferences as a point of departure, the Commission undertook this study of the wide-ranging civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Asian American groups considered in the report are persons having origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This report presents the results of that investigation. Evidence is presented that Asian Americans face widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity. The following chapters highlight specificareas: (1) "Introduction," an overview of the problems;(2) "Bigotry and Violence Against Asian Americans"; (3) "Police Community Relations"; (4) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Asian American Immigrant Children in Primary and Secondary Schools";(5) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Higher Education"; (6) "Employment Discrimination";(7) "Other Civil Rights Issues Confronting Asian AmericansH; and (8) "Conclusions and Recommendations." More than 40 recommendations for legislative, programmatic, and administrative efforts are made. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Open Casket: Post-Mortem Asian American Resonances and Performances of Mourning and Justice Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4jr14578 Author Lee, Mitchell Katsu Publication Date 2018 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Open Casket: Post-Mortem Asian American Resonances and Performances of Mourning and Justice A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts in Asian American Studies by Mitchell Katsu Lee 2018 © Copyright by Mitchell Katsu Lee 2018 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Open Casket: Post-Mortem Asian American Resonances and Performances of Mourning and Justice by Mitchell Katsu Lee Master of Arts in Asian American Studies University of California, Los Angeles 2018 Thu-Huong Nguyen-Vo, Chair This thesis examines Asian American racialization through instances of premature death as well processes of mourning and advocacy for the dead. I juxtapose Celeste Ng’s novel Everything I Never Told You with Season One of the podcast Serial in order to explore state procedures and the process of knowledge generation through the dead. I do so in order to consider the relationship between the state and the marginalized and address the gaps in the state’s epistemological processes. I also examine the death and after life of Vincent Chin. Chin has become an integral part of Asian American Studies because of the racial elements involved in his murder and the panethnic Asian American organizing that arose in the wake of his death. -

Asian-American Characters in Black Films and Black Activism

GET OUT, HIROKI TANAKA: ASIAN-AMERICAN CHARACTERS IN BLACK FILMS AND BLACK ACTIVISM by Naomi Yoko Ward Capstone submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for graduation with UNIVERSITY HONORS with a major in Communication Studies in the Department of Language, Philosophy, and Communication Studies Approved: Capstone Mentor Departmental Honors Advisor Dr. Jennifer Peeples Dr. Debra E. Monson ____________________________________ University Honors Program Director Dr. Kristine Miller UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, UT Spring 2020 1 Get Out, Hiroki Tanaka: Asian-Americans in Black Stories and Black Activism Naomi Yoko Ward Utah State University 2 Abstract The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship Asian-Americans have with black Americans in order to determine how Asian Americans navigate their role in American racial discourse. Additionally, this study considers the causes and effects of Asian-American participation in movements like Black Lives Matter (BLM). This topic is explored through the analysis of Asian-American characters in black stories told through four films: Fruitvale Station, Get Out, The Hate U Give, and Sorry to Bother You. To narrow the scope of this research, I placed focus on characters in works that have been published since 2013, when the Black Lives Matter movement was officially formed and founded. Media functions both as a reflection of the society it is made in as well as an influence on how society perceives the world. The pervasiveness and power that media has in the world, particularly concerning social issues and social justice, makes this lens appropriate for studying race relations in the United States over the past several years. -

Racializing Asian Americans in a Society Obsessed with OJ

Hastings Women’s Law Journal Volume 6 Article 4 Number 2 Seeing the Elephant 6-1-1995 Beyond Black and White: Racializing Asian Americans in a Society Obsessed with O.J. Cynthia Kwei Yung Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj Recommended Citation Cynthia Kwei Yung Lee, Beyond Black and White: Racializing Asian Americans in a Society Obsessed with O.J., 6 Hastings Women's L.J. 165 (1995). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hwlj/vol6/iss2/4 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Women’s Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Beyond Black and White: Racializing Asian Americans in a Society Obsessed with 0.1. Cynthia Kwei Yung Lee* I. Introduction The 0.1. Simpson double murder trial has been called the "Trial of the 2 Century" I and has captured the attention of millions. The trial has raised interesting questions about the convergence of issues regarding race, class, and gender. 3 Rather than extensively discussing these global issues, * The author is an Associate Professor of Law at the University of San Diego School of Law. She received an A.B. from Stanford University and a J.D. from the University of California at Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. First and foremost, she wishes to thank her good friend Robert Chang who, through his own scholarship, encouraged her to write this essay. -

Aapis Connect: Harnessing Strategic Communications to Advance Civic Engagement

AAPIs Connect: Harnessing Strategic Communications to Advance Civic Engagement AAPI CIVIC ENGAGEMENT FUND & UCLA CENTER FOR NEIGHBORHOOD KNOWLEDGE 2020 Table of Contents Executive Summary 2 Useful Definitions 7 Introduction 8 Demographics: Asian American and Pacific Islander Communities 13 Literature Review: AAPI Communications and Community-led Media 20 Survey: AAPI Civic Engagement Fund Cohort 30 Conversations with Media Makers 32 Jen Soriano on Strategic Communications for Social Justice Social Media Tips Renee Tajima-Pena on Collaborations with Filmmakers Ethnic Media Tips Capacity Building Initiatives and Collaborations Conclusion 52 Acknowledgments 54 References 55 Appendix A: Literature Review Methodology 60 Appendix B: Supplemental Documentation for Survey 61 Executive Summary Stories have always been the most compelling way to motivate people to participate in the democratic process and change the hearts and minds of everyday individuals. The explosion of digital communications platforms has expanded opportunities and given rise to new approaches to reach and activate diverse audiences. Unfortunately, these new platforms have also become vehicles for fomenting intolerance, fear, and misinformation as well as isolating and cementing divisions among communities. America is both more connected and more disconnected. In these times, when hate and violence are on the rise, stories of communities mobilizing together against injustice or inhumane policies are urgently needed. Too often the voices and spirit of progressive Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) are absent in any such public discourse. Meanwhile, there is a false narrative of the AAPI community as apathetic or conservative. With the goal of supporting greater narrative power for AAPIs, the AAPI Civic Engagement Fund is pursuing a multipronged strategy that enables a cohort1 of local AAPI groups to craft and promote stories by, for, and about the community by assessing their needs and building their capacity. -

Issue Brief #160: Asian American Protest Politics “The Politics of Identity”

Issue Brief #160: Asian American Protest Politics “The Politics of Identity” Key Words Political visibility, Yellow Power Movement, pan-Asian American identity, model minority, perpetual foreigners, reverse discrimination Description This brief seeks to review the history of Asian American protest movements in the twentieth century and the political ramifications of historic Asian American stereotypes, such as the “model minority” and “perpetual foreigner” prejudices. It also assesses the consequences of these myths that may unfold if Asian Americans continue to feel excluded from political culture and society. Key Points Asians currently constitute five percent of the American population, and this small percentage may contribute to their seemingly low political visibility. Furthermore, immigration to the United States by Asians is a relatively recent phenomenon, with small numbers arriving in the 1830s followed by decades of restricted access and exclusion from citizenship. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s when legal changes facilitated Asian immigration to the United States. Spikes of high arrival have occurred throughout the past decades. Today, Asians represent the fastest growing immigrant group in the United States, which has enormous political implications. (See U.S. Census reference) Like most other immigrant groups, Asian Americans seek racial equality, social justice, and political empowerment. Their mobilization has often been based on an inter-Asian coalition based on a pan-Asian identity. However, in light of this sweeping categorization, the most recent Asian American ethnic consciousness movements have highlighted the diversity of peoples included within this broad pan-ethnic category. (See Lien, Nguyen) Asian Americans seek to imbue their pan-ethnic identity with new definition and depth by protesting the stereotypes and caricatures that diminish them as individuals. -

Toward an Asian American Legal Scholarship: Critical Race Theory, Post-Structuralism, and Narrative Space

Toward an Asian American Legal Scholarship: Critical Race Theory, Post-Structuralism, and Narrative Space Robert S. Chang TABLE OF CONTENTS Prelude ........................................ 1243 Introduction: Mapping the Terrain ............................. 1247 I. The Need for an Asian American Legal Scholarship ........ 1251 A. That Was Then, This Is Now: Variations on a Theme .. 1251 1. Violence Against Asian Americans ................. 1252 2. Nativistic Racism .................................. 1255 B. The Model Minority Myth ............................. 1258 C. The Inadequacy of the Current Racial Paradigm ........ 1265 1. Traditional Civil Rights Work ...................... 1265 2. Critical Race Scholarships .......................... 1266 II. Narrative Space ........................................... 1268 A. Perspective Matters ................................... 1272 B. Resistance to Narrative ................................ 1273 C. Epistemological Strategies .............................. 1278 1. Arguing in the Rational/Empirical Mode ........... 1279 2. Post-Structuralism and the Narrative Turn .......... 1284 III. The Asian American Experience: A Narrative Account of Exclusion and Marginalization ............................. 1286 A. Exclusion from Legal and Political Participation ........ 1289 1. Immigration and Naturalization .................... 1289 2. Disfranchisement .................................. 1300 B. Speaking Our Oppression into (and out of) Existence ... 1303 1. The Japanese American Internment and Redress