The Future of the Finno-Ugric Languages of Russia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

REFORM of POLLUTION CHARGES in the RUSSIAN FEDERATION: Assessment of Progress and Opportunities and Constraints for Further Improvement

REFORM OF POLLUTION CHARGES IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION: Assessment of Progress and Opportunities and Constraints for Further Improvement OECD ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT ORGANISATION FOR ECONOMIC CO-OPERATION AND DEVELOPMENT The OECD is a unique forum where the governments of 30 democracies work together to address the economic, social and environmental challenges of globalisation. The OECD is also at the forefront of efforts to understand and to help governments respond to new developments and concerns, such as corporate governance, the information economy, and the challenges of an ageing population. The Organisation provides a setting where governments can compare policy experiences, seek answers to common problems, identify good practice, and work to co-ordinate domestic and international policies. The OECD Member countries are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Japan, Korea, Luxembourg, Mexico, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, the United Kingdom, and the United States. The Commission of the European Communities takes part in the work of the OECD. OECD Publishing disseminates widely the results of the statistics gathered by the Organisation and its research on economic, social, and environmental issues, as well as the conventions, guidelines, and standards agreed by its Members. This work is published on the responsibility of the Secretary-General of the OECD. The opinions expressed and arguments employed herein do not necessarily reflect the official views of the Organisation or of the governments of its Member countries. © OECD (2004) No reproduction, copy, transmission or translation of this publication may be made without written permission. -

The Situation of Minority Children in Russia

The Situation of Children Belonging to Vulnerable Groups in Russia Alternative Report March 2013 Anti- Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL” The NGO, Anti-Discrimination Centre “MEMORIAL”, was registered in 2007 and continued work on a number of human rights and anti-discrimination projects previously coordinated by the Charitable Educational Human Rights NGO “MEMORIAL” of St. Petersburg. ADC “Memorial‟s mission is to defend the rights of individuals subject to or at risk of discrimination by providing a proactive response to human rights violations, including legal assistance, human rights education, research, and publications. ADC Memorial‟s strategic goals are the total eradication of discrimination at state level; the adoption of anti- discrimination legislation in Russia; overcoming all forms of racism and nationalism; Human Rights education; and building tolerance among the Russian people. ADC Memorial‟s vision is the recognition of non-discrimination as a precondition for the realization of all the rights of each person. Tel: +7 (812) 317-89-30 E-mail: [email protected] Contributors The report has been prepared by Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” with editorial direction of Stephania Kulaeva and Olga Abramenko. Anti-discrimination Center “Memorial” would like to thank Simon Papuashvili of International Partnership for Human Rights for his assistance in putting this report together and Ksenia Orlova of ADC “Memorial” for allowing us to use the picture for the cover page. Page 2 of 47 Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 4 Summary of Recommendations ..................................................................................................... 7 Overview of the legal and policy initiatives implemented in the reporting period ................. 11 Violations of the rights of children involving law enforcement agencies ............................... -

Russian NGO Shadow Report on the Observance of the Convention

Russian NGO Shadow Report on the Observance of the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment by the Russian Federation for the period from 2001 to 2005 Moscow, May 2006 CONTENT Introduction .......................................................................................................................................4 Summary...........................................................................................................................................5 Article 2 ..........................................................................................................................................14 Measures taken to improve the conditions in detention facilities .............................................14 Measures to improve the situation in penal institutions and protection of prisoners’ human rights ..........................................................................................................................................15 Measures taken to improve the situation in temporary isolation wards of the Russian Ministry for Internal Affairs and other custodial places ..........................................................................16 Measures taken to prevent torture and cruel and depredating treatment in work of police and other law-enforcement institutions ............................................................................................16 Measures taken to prevent cruel treatment in the armed forces ................................................17 -

A Simple Mechanistic Model of the Invasive Species Heracleum Sosnowskyi Propagule Dispersal by Wind

A simple mechanistic model of the invasive species Heracleum sosnowskyi propagule dispersal by wind Ivan Chadin1, Igor Dalke2, Denis Tishin3, Ilya Zakhozhiy2 and Ruslan Malyshev2 1 Molecular Biology Facility, Institute of Biology of Komi Science Centre of Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Syktyvkar, Komi Republic, Russian Federation 2 Laboratory of Plant Ecological Physiology, Institute of Biology of Komi Science Centre of Ural Branch of Russian Academy of Sciences, Syktyvkar, Komi Republic, Russia 3 Institute of Environmental Sciences, Kazan Federal University, Kazan, Republic of Tatarstan, Russian Federation ABSTRACT Background. Invasive species are one of the key elements of human-mediated ecosystem degradation and ecosystem services impairment worldwide. Dispersal of propagules is the first stage of plant species spread and strongly influences the dynamics of biological invasion. Therefore, distance prediction for invasive species spread is critical for invasion management. Heracleum sosnowskyi is one of the most dangerous invasive species with wind-dispersed propagules (seeds) across Eastern Europe. This study developed a simple mechanistic model for H. sosnowskyi propagule dispersal and their distances with an accuracy comparable to that of empirical measurements. Methods. We measured and compared the propagule traits (terminal velocity, mass, area, and wing loading) and release height for H. sosnowskyi populations from two geographically distant regions of European Russia. We tested two simple mechanistic models: a ballistic model and a wind gradient model using identical artificial propagules. The artificial propagules were made of colored paper with a mass, area, wing loading, and terminal velocity close to those of natural H. sosnowskyi mericarps. Results. The wind gradient model produced the best results. -

Komiaviatrans Obtained a License to Start Flying to Europe. Komiaviatrans Pdf Version

50SKYSHADESImage not found or type unknown- aviation news KOMIAVIATRANS OBTAINED A LICENSE TO START FLYING TO EUROPE News / Airlines Image not found or type unknown Komiaviatrans, a carrier active in the Komi Republic of Russia, has obtained a license from the Russian aviation authorities to start flying to Europe, with Tallinn named as a potential destination. © 2015-2021 50SKYSHADES.COM — Reproduction, copying, or redistribution for commercial purposes is prohibited. 1 The license obtained enables the company to fly from the Komi Republic to countries of Europe. For instance, the company can fly to Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Tallinn and Baku with a stopover in St. Petersburg, the Russian Ministry of Industry and Transport said. In addition Komiaviatrans is planning new services within Russia and will launch a Syktyvkar-Sochi service with a landing in Perm still this month. Service on the Syktyvkar-Kazan route is to start in 2016. To serve the new operations, the company is planning to lease two more Embraer ERJ-145 jets shortly. At the beginning of this year Komiaviatrans started direct regular flights from Syktyvkar, capital of the Komi Republic, to Moscow, St. Petersburg, Yekaterinburg, Samara, Perm, Kirov and Naryan- Mar. The company also operates services between Uhta and Moscow and between Usinsk and Moscow, St. Petersburg and Ufa. In the summer flights are operated from Syktyvkar to Krasnodar, Anapa and Mineralnyie Vody. Komiaviatrans is active mainly in the Komi Republic and in the Nenets and Yamalo-Nenets autonomous regions in north-central Russia and it operates the airports of Syktyvkar, Uhta, Sinsk, Vorkuta, Pechora, Vuktyl, Ust-Tsilma and Inta. -

2012 Membership Directory

2012 Membership Directory “Sister Cities International has been instrumental in breaking down barriers between cultures and fostering better relations between communities separated by oceans.” —President William Jefferson Clinton 2 0 1 2 M e m b e r s h i p D i r e c t o r y b y U . S . S t a t e Alabama Arizona Arkansas Birmingham / POP 229,800 Chandler / POP 252,017 Heber Springs / POP 7,308 Al-Karak, Jordan Tullamore, Ireland Omoa, Honduras Anshan, China Chao Yang District, China Fountain Hills / POP 24,669 Hot Springs / POP 35,183 Coban, Guatemala Ataco, El Salvador Hamamaki, Japan Guediawaye, Senegal Dierdorf, Germany Gweru, Zimbabwe Kasterlee, Belgium Little Rock / POP 187,452 Hitachi, Japan Changchun, China Huangshi, China Gila Bend / POP 1,834 England, Newcastle upon Tyne Maebashi City, Japan No Reported Sister City Hanam City, Republic of Korea Plzen, Czech Republic Kaohsiung Municipality, Taiwan Pomigliano d’Arco, Italy Gilbert / POP 207,500 Mons, Belgium Rosh Ha’ayin, Israel Leshan, China Szekesfehervar, Hungary Newtownabbey, United Kingdom Marion / POP 12,217 Vinnytsya, Ukraine No Reported Sister City Winneba, Ghana Mesa / POP 452,933 Burnaby, Canada North Little Rock / POP 60,140 Mobile / POP 192,830 Caraz, Peru Uiwang City, Republic of Korea Ariel, Israel Guaymas, Mexico Bolinao, Philippines Kaiping, China St. Joe / POP 28 Cockburn, Australia New Zealand Bride, Isle of Mann, United Kingdom Constanta, Romania Gaeta, Italy Phoenix / POP 1,567,924 California Gianjin, China Calgary, Canada Alameda / POP 70,272 Havana, -

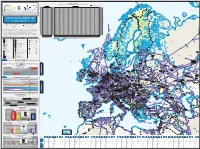

System Development Map 2019 / 2020 Presents Existing Infrastructure & Capacity from the Perspective of the Year 2020

7125/1-1 7124/3-1 SNØHVIT ASKELADD ALBATROSS 7122/6-1 7125/4-1 ALBATROSS S ASKELADD W GOLIAT 7128/4-1 Novaya Import & Transmission Capacity Zemlya 17 December 2020 (GWh/d) ALKE JAN MAYEN (Values submitted by TSO from Transparency Platform-the lowest value between the values submitted by cross border TSOs) Key DEg market area GASPOOL Den market area Net Connect Germany Barents Sea Import Capacities Cross-Border Capacities Hammerfest AZ DZ LNG LY NO RU TR AT BE BG CH CZ DEg DEn DK EE ES FI FR GR HR HU IE IT LT LU LV MD MK NL PL PT RO RS RU SE SI SK SM TR UA UK AT 0 AT 350 194 1.570 2.114 AT KILDIN N BE 477 488 965 BE 131 189 270 1.437 652 2.679 BE BG 577 577 BG 65 806 21 892 BG CH 0 CH 349 258 444 1.051 CH Pechora Sea CZ 0 CZ 2.306 400 2.706 CZ MURMAN DEg 511 2.973 3.484 DEg 129 335 34 330 932 1.760 DEg DEn 729 729 DEn 390 268 164 896 593 4 1.116 3.431 DEn MURMANSK DK 0 DK 101 23 124 DK GULYAYEV N PESCHANO-OZER EE 27 27 EE 10 168 10 EE PIRAZLOM Kolguyev POMOR ES 732 1.911 2.642 ES 165 80 245 ES Island Murmansk FI 220 220 FI 40 - FI FR 809 590 1.399 FR 850 100 609 224 1.783 FR GR 350 205 49 604 GR 118 118 GR BELUZEY HR 77 77 HR 77 54 131 HR Pomoriy SYSTEM DEVELOPMENT MAP HU 517 517 HU 153 49 50 129 517 381 HU Strait IE 0 IE 385 385 IE Kanin Peninsula IT 1.138 601 420 2.159 IT 1.150 640 291 22 2.103 IT TO TO LT 122 325 447 LT 65 65 LT 2019 / 2020 LU 0 LU 49 24 73 LU Kola Peninsula LV 63 63 LV 68 68 LV MD 0 MD 16 16 MD AASTA HANSTEEN Kandalaksha Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 Avenue de Cortenbergh 100 MK 0 MK 20 20 MK 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM 1000 Brussels - BELGIUM NL 418 963 1.381 NL 393 348 245 168 1.154 NL T +32 2 894 51 00 T +32 2 209 05 00 PL 158 1.336 1.494 PL 28 234 262 PL Twitter @ENTSOG Twitter @GIEBrussels PT 200 200 PT 144 144 PT [email protected] [email protected] RO 1.114 RO 148 77 RO www.entsog.eu www.gie.eu 1.114 225 RS 0 RS 174 142 316 RS The System Development Map 2019 / 2020 presents existing infrastructure & capacity from the perspective of the year 2020. -

Russian Report

Foundation for Internet Development Lomonosov Moscow State University, Department of Psychology Russian Kids Online Key findings of the EU Kids Online II survey in Russia Galina Soldatova, Elena Rasskazova, Ekaterina Zotova, Maria Lebesheva, Marina Geer and Polina Roggendorf 1 The authors would like to express gratitude for all the help in the process of conducting the survey, for consulting and support during data analysis Prof. Dr. Sonia Livingstone, Dr. Leslie Haddon, Dr. Brian O’Neill, Prof. Dr. Uwe Hasebrink, as well as the entire united and experienced team of the EU Kids Online II project. We are also very grateful to the whole Russian team for their help during the survey in Russian regions: Tatiana Yanicheva (Saint-Petersburg University), Olga Uvarovskaya (Syktyvkar State University), Svetlana Kasimova (Vyatsky State University), Margarita Pavlova (Saratov Institute for Continued Education and further training), Tatiana Skripkina amd Tatiana Scherbakova (Rostov State University), Andrei Shatin and Alexander Vokhmintsev (Chelyabinsk State University), Mikhail Ivanov (Kemerovsky State University), Elmira Isaeva (Dagestan State University), and Elvira Vandanova (Chita State University). 2 CONTENTS KEY FINDINGS ........................................................................................................................... 5 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 12 2. USAGE OF THE INTERNET ................................................................................................ -

Notes on Russian Indianists

Notes on Russian Indianists O. Y. Danchevskaya Moscow State Pedagogical University In the present-day world seized by the process of fast technical development, urban-ization, and globalization, more and more people feel a need for the natural lifeway, the return to initial human values. They look for answers to numerous questions in the history, cultures, philosophies, religions, and traditions of the nations and tribes who have tried to carefully preserve the order of the universe and harmony with nature. Native American tribes are some of the brightest representatives of such cultures, in many respects due to the fact that “even today it is possible to live according to American Indian ideals, and one of the reasons for it is that those cultures are themselves alive.”1 At first sight, it may seem strange that in Russia, which is far-away from the USA, there have appeared many people who not only express an unfeigned interest in the cultures of North American Indians, but also practice their philosophy. However, the historical connections between these two countries should not be forgotten: the communication between the continents via the Bering Strait, “the heroic épopée of Russian America” in the 18th-19th centuries,2 and the purchase of Alaska by the USA from Russia in 1867. Undoubtedly, mere imitators can also be found among such admirers, but still hundreds of people in Russia can be rightly regarded as Indianists. It is worth explaining who is meant by “Indianists,” as this term often bears the wrong connotation. At the end of the 20th century in U.S. -

Issues of Health Evaluation During Simulated Space Mission to Mars Part 3

Open access journal Practice CARDIOMETRY Report Issues of health evaluation during simulated space mission to Mars Part 3. Assessment of adaptation reactions in the participants of the long-term medical & ecological investigations during the experiment Mars-500 Roman M. Baevsky 1, Azalia P. Berseneva 1, Irina N. Slepchenkova 1, 1* Anna G. Chernikova 1 State Scientific Center of the Russian Federation, Institute of Biomedical Problems of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 123007, Russia, Moscow, 76A Khoroshevskoye Ch. * Corresponding author: Phone: +7 (499) 193-62-44. E-mail: [email protected] Submitted: 16 March 2013 Accepted: 10 April 2013 Published online: 30 May 2013 Abstract The paper presents the results of the long-term medical & ecological investigations conducted during the experiment Mars-500. Methodology of conducting the long-term medical & ecological investigations and the applied methods are considered. The results are presented in the materials of the research conducted in Russian Federation and Republic of Belarus (Moscow, Syktyvkar, Yekaterinburg, Izhevsk, Magadan and Minsk). For comparative evaluation of the functional state of different reference groups the notion of “ecological stress” was introduced. It depends upon the degree of dominance of the activity of the sympathetic member of the regulatory system over the parasympathetic member. Application of probabilistic approach to the assessment of the functional state and adaptation level with the FR (functional reserve) and the DT (the degree of tension) of the regulatory mechanisms proved the detected peculiarities of the heart rhythm vegetative regulation. Clear dependency of the functional state of the volunteers on geographic location of regions and climatic parameters is observed. -

Giant Maps Europe

KILOMETERS KILOMETERS 70° 55° 50°W 45° 40° 80° 35° 30° 25° 20° 15° 10° 5°W 0° 5°E 10° 15° 20° 25° 30° 35° 40° 45° 50° 55° 60° 65° 70° 75° 80° 85° 90° 95°E 100°E 400 300 200 100 400 300 200 100 0 0 75° 80° 75° 70° STATUTE MILES STATUTE STATUTE MILES STATUTE Ostrova Belaya Zemlya A 400 300 200 100 400 300 200 100 0 0 Ostrov Rudolph AZIMUTHAL EQUIDISTANT PROJECTION EQUIDISTANT AZIMUTHAL AZIMUTHAL EQUIDISTANT PROJECTION EQUIDISTANT AZIMUTHAL Ost Ostrov Graham rov Bell Ostrov Vize (London) J No shoes or writing utensils on map on utensils writing or shoes No ack son Meridian of Greenwich E Zemlya Wilczek n E NE W A Ostrov N NW D A N a Salisbury F Arctic Ocean Ostrov Hall I SE SW r S e O I D) c c S NW N Ostrov Arthur N t E Ostrov A S S O A NE ) i S T c Zemlya George Hooker T L SW N F W SE E E A 55° 65° A R A S A Burkhta Tikhaya F J O 65° Zemlya Alexandra A Y Z Russia L N L A N Sjuøyane E M F R U Z ( Ostrov Victoria N Lågøya Kvitøya N Storøya D T Danskøya R A I Nordaustlandet 95°E C E L Denmark A Nuuk L B Ny Ålesund A (Godth˚ab) E A E L Spitsbergen Norway Kongsøya R 50° A Prins Karls Forland Svenskøya Y L A Kong Karls R L Longyearbyen Barentsøya Land Ostrov Pankrat'yeva A E V Barentsburg E K A M A ( S G E Edgeøya S E D Z 90° K N A A Sørkappøya Hopen L E A 45° S Y N E L S C A IR E T C E N IC T E V E C B A R R A R O A R C T IC G Bjørnøya N C IR (Bear Island) 85° C L E E D e Ostrov n m a r k Belush'ya Guba S t Vaygach r a i 60° 40° t Jan Mayen E Norway Ostrov Mezhdusharskiy Vorkuta 60° A a y E h Cape a Nort k B s r N S H Berlev˚ag Kolguyev ' Ob e a E Island 80° iða i S mm l Ob fj l´o ør e e örð f øy rf a A ur na a es a E u´ Lop t E Varanger Pen.