Russian NGO Shadow Report on the Observance of the Convention

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Wolf Attacks - Wikipedia

List of wolf attacks - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wolf_attacks List of wolf attacks This is a list of significant wolf attacks worldwide, by century, in reverse chronological order. Contents 2010s 2000s 1900s 1800s 1700s See also References Bibliography 2010s 1 von 28 14.03.2018, 14:46 List of wolf attacks - Wikipedia https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_wolf_attacks Type of Victim(s) Age Gender Date Location Details Source(s) attack A wolf attacked the woman in the yard when she was busy with the household. First it bit her right arm and then tried to snap her throat .A Omyt Village, Zarechni bucket which she used to protect Lydia Vladimirovna 70 ♀ January 19, 2018 Rabid District, Rivne Region, her throat saved her life as the [1][2] Ukraine rabid animal furiously ripped the bucket. A Neighbor shot the wolf which was tested rabid. The attacked lady got the necessary medical treatments. 2-3 wolves strayed through a small village. Within 10 hours starting at 9 p.m.one of them attacked and hurt 4 people. Lina Zaporozhets Anna Lushchik, Vladimir was saved by her laptop. When the A Village, Koropsky Kiryanov , Lyubov wolf bit into it, she could escape 63, 59, 53, 14 ♀/♂/♂/♀ January 4, 2018 Unprovoked District, Chernihiv [3][4] Gerashchenko, Lina through the door of her yard.The Region Ukraine. Zaporozhets injured were treated in the Koropsky Central District Hospital. One of the wolves was shot in the middle of the village and sent to rabies examination. At intervals of 40 minutes a wolf attacked two men. -

Optimization of Regional Public Transport System: the Case of Perm Krai

Elena Koncheva, Nikolay Zalesskiy, Pavel Zuzin OPTIMIZATION OF REGIONAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT SYSTEM: THE CASE OF PERM KRAI BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: URBAN AND TRANSPORTATION STUDIES WP BRP 01/URB/2015 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE. 1 1 2 2 3 Elena Koncheva , Nikolay Zalesskiy , Pavel Zuzin OPTIMIZATION OF REGIONAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT SYSTEM: THE CASE OF PERM KRAI4 Liberalization of regional public transport market in Russia has led to continuing decline of service quality. One of the main results of the liberalization is the emergence of inefficient spatial structures of regional public transport systems in Russian regions. While the problem of optimization of urban public transport system has been extensively studied, the structure of regional public transport system has been referred less often. The question is whether the problems of spatial structure are common for regional and public transportation systems, and if this is the case, whether the techniques developed for urban public transport planning and management are applicable to regional networks. The analysis of the regional public transport system in Perm Krai has shown that the problems of cities and regions are very similar. On this evidence the proposals were made in order to employ urban practice for the optimization of regional public transport system. The detailed program was developed for Perm Krai which can be later on adapted for other regions. JEL Classification: R42. -

Voter Alignments in a Dominant Party System: the Cleavage Structures of the Russian Federation

Voter alignments in a dominant party system: The cleavage structures of the Russian Federation. Master’s Thesis Department of Comparative Politics November 2015 Ivanna Petrova Abstract This thesis investigates whether there is a social cleavage structure across the Russian regions and whether this structure is mirrored in the electoral vote shares for Putin and his party United Russia on one hand, versus the Communist Party of the Russian Federation and its leader Gennady Zyuganov on the other. In addition to mapping different economic, demographic and cultural factors affecting regional vote shares, this thesis attempts to determine whether there is a party system based on social cleavages in Russia. In addition, as the Russian context is heavily influenced by the president, this thesis investigates whether the same cleavages can explain the distribution of vote shares during the presidential elections. Unemployment, pensioners, printed newspapers and ethnicity create opposing effects during parliamentary elections, while distance to Moscow, income, pensioners, life expectancy, printed newspapers and ethnicity created opposing effects during the presidential elections. The first finding of this thesis is not only that the Russian party system is rooted in social cleavages, but that it appears to be based on the traditional “left-right” cleavage that characterizes all Western industrialized countries. In addition, despite the fact that Putin pulls voters from all segments of the society, the pattern found for the party system persists during presidential elections. The concluding finding shows that the main political cleavage in today’s Russia is between the left represented by the communists and the right represented by the incumbents. -

COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 2005 Amending for The

L 340/70EN Official Journal of the European Union 23.12.2005 COMMISSION DECISION of 21 December 2005 amending for the second time Decision 2005/693/EC concerning certain protection measures in relation to avian influenza in Russia (notified under document number C(2005) 5563) (Text with EEA relevance) (2005/933/EC) THE COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES, cessed parts of feathers from those regions of Russia listed in Annex I to that Decision. Having regard to the Treaty establishing the European Community, (3) Outbreaks of avian influenza continue to occur in certain parts of Russia and it is therefore necessary to prolong the measures provided for in Decision 2005/693/EC. The Decision can however be reviewed before this date depending on information supplied by the competent Having regard to Council Directive 91/496/EEC of 15 July 1991 veterinary authorities of Russia. laying down the principles governing the organisation of veterinary checks on animals entering the Community from third countries and amending Directives 89/662/EEC, 90/425/EEC and 90/675/EEC (1), and in particular Article 18(7) thereof, (4) The outbreaks in the European part of Russia have all occurred in the central area and no outbreaks have occurred in the northern regions. It is therefore no longer necessary to continue the suspension of imports of unprocessed feathers and parts of feathers from the Having regard to Council Directive 97/78/EC of 18 December latter. 1997 laying down the principles governing the organisation of veterinary checks on products entering the Community from third countries (2), and in particular Article 22 (6) thereof, (5) Decision 2005/693/EC should therefore be amended accordingly. -

Health Sector Field Directory

HEALTH SECTOR FIELD DIRECTORY Republic of Chechnya Republic of Ingushetia Russian Federation June 2004 World Health Organization Nazran, Republic of Ingushetia TABLE OF CONTENTS ORGANIZATION 1. Agency for Rehabilitation and Development (ARD/Denal) 2. CARE Canada 3. Centre for Peacemaking and Community Development (CPCD) 4. Danish Refugee Council/Danish Peoples Aid (DRC/DPA) 5. Hammer FOrum e. V. 6. Handicap International 7. International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) 8. International Humanitarian Initiative (IHI) 9. International Medical Corps (IMC) 10. Islamic Relief (IR) 11. International Rescue Committee (IRC) 12. Medecins du Monde (MDM) 13. Medecins Sans Frontieres – Belgium (MSF-B) 14. Error! Reference source not found. 15. Medecins Sans Frontieres - Holland (MSF-H) 16. Medecins Sans Frontieres - Switzerland (MSF-CH) 17. Memorial 18. People in Need (PIN) 19. Polish Humanitarian Organisation (PHO) 20. Save the Generation 21. SERLO 22. UNICEF 23. World Vision 24. World Health Organization (WHO) 2 Agency for Rehabilitation and Development (ARD/Denal) Sector: Health; Food; Non-Food Items; Education Location: Chechnya and Ingushetia Objectives: To render psychosocial support to people affected by the conflict; to provide specialised medical services for women and medical aid for the IDP population; to support education and recreational activities; to supply supplementary food products to vulnerable IDP categories with specific nutritional needs; to provide basic hygienic items and clothes for new-born; to help the IDP community to establish a support system for its members making use of available resources. Beneficiaries: IDP children, youth, women and men in Ingushetia and residents in Chechnya Partners: UNICEF, SDC/SHA CONTACT INFORMATION: INGUSHETIA Moscow Karabulak, Evdoshenko St. -

Information for Persons Who Wish to Seek Asylum in the Russian Federation

INFORMATION FOR PERSONS WHO WISH TO SEEK ASYLUM IN THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION “Everyone has the right to seek and to enjoy in the other countries asylum from persecution”. Article 14 Universal Declaration of Human Rights I. Who is a refugee? According to Article 1 of the Federal Law “On Refugees”, a refugee is: “a person who, owing to well‑founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of particular social group or politi‑ cal opinion, is outside the country of his nationality and is unable or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself of the protection of that country”. If you consider yourself a refugee, you should apply for Refugee Status in the Russian Federation and obtain protection from the state. If you consider that you may not meet the refugee definition or you have already been rejected for refugee status, but, nevertheless you can not re‑ turn to your country of origin for humanitarian reasons, you have the right to submit an application for Temporary Asylum status, in accordance to the Article 12 of the Federal Law “On refugees”. Humanitarian reasons may con‑ stitute the following: being subjected to tortures, arbitrary deprivation of life and freedom, and access to emergency medical assistance in case of danger‑ ous disease / illness. II. Who is responsible for determining Refugee status? The responsibility for determining refugee status and providing le‑ gal protection as well as protection against forced return to the country of origin lies with the host state. Refugee status determination in the Russian Federation is conducted by the Federal Migration Service (FMS of Russia) through its territorial branches. -

HUMANITARIAN AID for the Victims of the Chechnya Conflict in the Caucasus

EUROPEAN COMMISSION DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR HUMANITARIAN AID - ECHO HUMANITARIAN AID for the victims of the Chechnya conflict in the Caucasus GLOBAL PLAN 2007 Humanitarian Aid Committee – December 2006 ECHO/-EE/BUD/2007/01000 1 Table of contents Explanatory Memorandum page 1) Executive summary..................................................................................... 3 2) Context and situation.................................................................................. 3 2.1.) General Context.................................................................................... 3 2.2.) Current Situation.................................................................................. 4 3) Identification and assessment of humanitarian needs.............................. 5 4) Proposed DG ECHO strategy....................................................................... 8 4.1.) Coherence with DG ECHO´s overall strategic priorities.................... 8 4.2.) Impact of previous humanitarian response......................................... 9 4.3.) Coordination with activities of other donors and institutions............ 10 4.4.) Risk assessment and assumptions........................................................ 10 4.5.) DG ECHO Strategy.................................................................................11 4.6.) Duration............................................................................................. 12 4.7.) Amount of decision and strategic programming matrix..................... 13 5) Evaluation............................................................................................. -

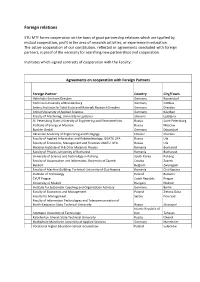

Foreign Relations

Foreign relations STU MTF forms cooperation on the basis of good partnership relations which are typified by mutual cooperation, profit in the area of research activities, or experience in education. The active cooperation of our constitution, reflected in agreements concluded with foreign partners, is proof of the necessity for searching new partnerships and cooperation. Institutes which signed contracts of cooperation with the Faculty: Agreements on cooperation with Foreign Partners Foreign Partner Country City/Town Helmholtz-Zentrum Dresden Germany Rossendorf Technical University of Brandenburg Germany Cottbus Leibniz-Institute for Solid State and Materials Research Dresden Germany Dresden Anhlat University of Applied Sciences Germany Koethen Faculty of Machining, University in Ljubljana Slovenia Ljubljana St. Petersburg State University of Engineering and Electrotechnics Russia Saint-Petersburg Institute of Energy in Moscow Russia Moscow Buehler GmbH Germany Düsseldorf Ukrainian Academy of Engineering and Pedagogy Ukraine Charkov Faculty of Applied Informatics and Robotechnology, UGATU UFA Russia Ufa Faculty of Economics, Management and Finances UGATU UFA Russia Ufa National Institute of R & D for Materials Physics Romania Bucharest Faculty of Physics, University of Bucharest Romania Bucharest University of Science and Technology in Pohang South Korea Pohang Faculty of Organisation and Informatics, University of Zagreb Croatia Zagreb Bekaert Belgium Zwevegem Faculty of Machine Building, Technical University of Cluj-Napoca Romania Cluj-Napoca -

Second Report Submitted by the Russian Federation Pursuant to The

ACFC/SR/II(2005)003 SECOND REPORT SUBMITTED BY THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 2 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES (Received on 26 April 2005) MINISTRY OF REGIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION REPORT OF THE RUSSIAN FEDERATION ON THE IMPLEMENTATION OF PROVISIONS OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES Report of the Russian Federation on the progress of the second cycle of monitoring in accordance with Article 25 of the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities MOSCOW, 2005 2 Table of contents PREAMBLE ..............................................................................................................................4 1. Introduction........................................................................................................................4 2. The legislation of the Russian Federation for the protection of national minorities rights5 3. Major lines of implementation of the law of the Russian Federation and the Framework Convention for the Protection of National Minorities .............................................................15 3.1. National territorial subdivisions...................................................................................15 3.2 Public associations – national cultural autonomies and national public organizations17 3.3 National minorities in the system of federal government............................................18 3.4 Development of Ethnic Communities’ National -

Countries and Their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by Spaceduck (Spaceduck) Via Cheatography.Com/4/Cs/56

Countries and their Capital Cities Cheat Sheet by SpaceDuck (SpaceDuck) via cheatography.com/4/cs/56/ Countries and their Captial Cities Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Countries and their Captial Cities (cont) Afghani stan Kabul Canada Ottawa Federated States of Palikir Albania Tirana Cape Verde Praia Micronesia Algeria Algiers Cayman Islands George Fiji Suva American Samoa Pago Pago Town Finland Helsinki Andorra Andorra la Vella Central African Republic Bangui France Paris Angola Luanda Chad N'Djamena French Polynesia Papeete Anguilla The Valley Chile Santiago Gabon Libreville Antigua and Barbuda St. John's Christmas Island Flying Fish Gambia Banjul Cove Argentina Buenos Aires Georgia Tbilisi Cocos (Keeling) Islands West Island Armenia Yerevan Germany Berlin Colombia Bogotá Aruba Oranjestad Ghana Accra Comoros Moroni Australia Canberra Gibraltar Gibraltar Cook Islands Avarua Austria Vienna Greece Athens Costa Rica San José Azerbaijan Baku Greenland Nuuk Côte d'Ivoire Yamous‐ Bahamas Nassau Grenada St. George's soukro Bahrain Manama Guam Hagåtña Croatia Zagreb Bangladesh Dhaka Guatemala Guatemala Cuba Havana City Barbados Bridgetown Cyprus Nicosia Guernsey St. Peter Port Belarus Minsk Czech Republic Prague Guinea Conakry Belgium Brussels Democratic Republic of the Kinshasa Guinea- Bissau Bissau Belize Belmopan Congo Guyana Georgetown Benin Porto-Novo Denmark Copenhagen Haiti Port-au -P‐ Bermuda Hamilton Djibouti Djibouti rince Bhutan Thimphu Dominica Roseau Honduras Tegucig alpa Bolivia Sucre Dominican Republic Santo -

Heterogeneity in Demand and Oprimal Price Conditioning for Local Rail Transportation

Heterogeneity in Demand and Oprimal Price Conditioning for Local Rail Transportation Evgeniy M. Ozhegov∗ National Research University Higher School of Economics. Research Group for Applied Markets and Enterprises Studies. Research fellow [email protected] Alina Ozhegova National Research University Higher School of Economics. Research Group for Applied Markets and Enterprises Studies. Junior research fellow [email protected] May 31, 2019 Abstract This paper describes the results of research project on optimal pricing for LLC "Perm Local Rail Company". In this study we propose a regression tree based approach for estimation of demand function for local rail tickets considering high degree of demand heterogeneity by various trip directions and the goals of travel. Employing detailed data on ticket sales for 5 years we estimate the parameters of demand function and reveal the significant variation in price elasticity of demand. While in average the demand is elastic by price, near a quarter of trips is characterized by weakly elastic demand. Lower elasticity of demand is correlated with lower degree of competition with other transport and inflexible frequency of travel. I. Introduction Local rail transportation in Russia is an important part of public transport system, as it is often the only way for people to move between locations. At the same time, due to the large length of the arXiv:1905.12859v1 [econ.EM] 30 May 2019 tracks and the distance between large settlements, regional passenger companies cannot cover the costs of operating local rail transport by the revenue from ticket sales. For instance, the revenue of LLC Perm Local Rail Company (PPK) in 2017 amounted to 596 million rubles (near 1 mln. -

The Second Chechen War: the Information Component

WARNING! The views expressed in FMSO publications and reports are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The Second Chechen War: The Information Component by Emil Pain, Former Russian Ethno-national Relations Advisor Translated by Mr. Robert R. Love Foreign Military Studies Office, Fort Leavenworth, KS. This article appeared in The linked image cannot be displayed. The file may have been moved, renamed, or deleted. Verify that the link points to the correct file a Military Review July-August 2000 In December 1994 Russian authorities made their first attempt to crush Chechen separatism militarily. However, after two years of bloody combat the Russian army was forced to withdraw from the Chechen Republic. The obstinacy of the Russian authorities who had decided on a policy of victory in Chechnya resulted in the deaths of at least 30,000 Chechens and 5,000 Russian soldiers.1 This war, which caused an estimated $5.5 billion in economic damage, was largely the cause of Russia's national economic crisis in 1998, when the Russian government proved unable to service its huge debts.2 It seemed that after the 1994-1996 war Russian society and the federal government realized the ineffectiveness of using colonial approaches to resolve ethnopolitical issues.3 They also understood, it seemed, the impossibility of forcibly imposing their will upon even a small ethnoterritorial community if a significant portion of that community is prepared to take up arms to defend its interests.