Mitral Valve Prolapse: Definition and Implications in Athletes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mitral Valve Prolapse

MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE WHAT IS MITRAL VALVE PROLAPSE? The mitral valve is a heart valve with two tissue flaps, called leaflets, that open and close. It is located between the left upper chamber (atrium) and left lower chamber (ventricle) of the heart. Mitral valve prolapse occurs when the mitral valve bulges into the left atrium when the heart contracts (squeezes). This may keep the leaflets from closing properly. The result is a backward flow of blood into the left atrium. This is referred to as leaking or regurgitation. Most of the time, however, mitral valve prolapse causes no symptoms and no problems. WHAT ARE THE SYMPTOMS? Most people with mitral valve prolapse have no symptoms. However, some have brief periods of rapid heartbeat or skipped beats. Some people have sharp chest pains lasting seconds or minutes. Some people have shortness of breath when climbing stairs or with heavy exertion. You may notice symptoms more when you are physically active HOW IS IT DIAGNOSED? Often mitral valve prolapse is discovered during a physical examination, when the doctor listens to your heart with a stethoscope. The valve leaflets create a “click” sound that the doctor may hear. If the valve leaks, the doctor may also hear a murmur. The doctor may ask you to stand, sit, lie down, or squat during your exam, so he or she can better hear the heart sounds. An echocardiogram passes sound waves through the heart to create an image. It is the best test to diagnose mitral valve prolapse. The images show the prolapse, any thickening of the valve leaflets, and any leakage of blood through the prolapsed valve. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: the Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features

diagnostics Review Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features Anna Giulia Pavon 1,2,*, Pierre Monney 1,2,3 and Juerg Schwitter 1,2,3 1 Cardiac MR Center (CRMC), Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland; [email protected] (P.M.); [email protected] (J.S.) 2 Cardiovascular Department, Division of Cardiology, Lausanne University Hospital (CHUV), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland 3 Faculty of Biology and Medicine, University of Lausanne (UniL), 1100 Lausanne, Switzerland * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +41-775-566-983 Abstract: Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) was first described in the 1960s, and it is usually a benign condition. However, a subtype of patients are known to have a higher incidence of ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death, the so called “arrhythmic MVP.” In recent years, several studies have been published to identify the most important clinical features to distinguish the benign form from the potentially lethal one in order to personalize patient’s treatment and follow-up. In this review, we specifically focused on red flags for increased arrhythmic risk to whom the cardiologist must be aware of while performing a cardiovascular imaging evaluation in patients with MVP. Keywords: mitral valve prolapse; arrhythmias; cardiovascular magnetic resonance Citation: Pavon, A.G.; Monney, P.; Schwitter, J. Mitral Valve Prolapse, Arrhythmias, and Sudden Cardiac Death: The Role of Multimodality 1. Mitral Valve and Arrhythmias: A Long Story Short Imaging to Detect High-Risk Features. In the recent years, the scientific community has begun to pay increasing attention Diagnostics 2021, 11, 683. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse Page 1 of 3

Mitral valve prolapse Page 1 of 3 Mitral valve prolapse Definition Mitral valve prolapse is a heart problem in which the valve that separates the upper and lower chambers of the left side of the heart does not close properly. Alternative Names Barlow syndrome; Floppy mitral valve; Myxomatous mitral valve; Billowing mitral valve; Systolic click-murmur syndrome; Prolapsing mitral leaflet syndrome Causes The mitral valve helps blood on the left side of the heart flow in one direction. It closes to keep blood from moving backwards when the heart beats (contracts). Mitral valve prolapse is the term used when the valve does not close properly. It can be caused by many different things. In most cases, it is harmless and patients usually do not know they have the problem. As much as 10% of the population has some minor, insignificant form of mitral valve prolapse, but it does not generally affect their lifestyle. In a small number of cases, the prolapse can cause blood to leak backwards. This is called mitral regurgitation. Mitral valves that are structurally abnormal can raise the risk for bacterial infection. Some forms of mitral valve prolapse seem to be passed down through families (inherited). Mitral valve prolapse has been associated with Graves disease . Mitral valve prolapse often affects thin women who may have minor chest wall deformities, scoliosis , or other disorders. Mitral valve prolapse is associated with some connective tissue disorders, especially Marfan syndrome . Other conditions include: • Ehlers-Danlos syndrome • Osteogenesis imperfecta • Polycystic kidney disease http://eclinicalworks.adam.com/content.aspx?ref=applications.adam.com&url=eclinicalwo .. -

Mitral Valve Regurgitation

MITRAL VALVE REGURGITATION WHAT IS MITRAL VALVE REGURGITATION? The mitral valve is on the left side of the heart between the left upper chamber (atrium) and lower chamber (ventricle). The valve has two flaps called leaflets that normally close every time the ventricle squeezes to pump blood out of the heart. When the mitral valve doesn't close properly, some of the blood from the ventricle is forced back up (regurgitated) into the left atrium instead of flowing out to the rest of the body. The added workload on the heart and the increased blood pressure in the lungs eventually cause problems. HOW DOES IT OCCUR? Rheumatic fever can damage the mitral valve leaflets and cause scarring. The scars deform the leaflets so that they don't close properly, and regurgitation occurs. A condition called mitral valve prolapse can also cause mitral regurgitation. With mitral valve prolapse, one or both of the leaflets bulge (prolapse) into the left atrium. A small amount of mitral regurgitation (MR) is common with mitral valve prolapse. If one or more of the structures attaching the leaflets to the heart muscle breaks, the valve may leak. Heart attacks, diseases of the heart muscle, or other heart valve abnormalities may cause the whole heart to enlarge. The enlargement stretches the mitral valve ring and muscular attachments, pulling the valve leaflets apart. When the leaflets no longer meet, leaking of the mitral valve (MR) results. Over time, the added workload on the heart may cause congestive heart failure. Congestive heart failure occurs when the heart can't pump enough blood to keep the lungs or other body tissues from filling with fluid. -

Valve Disease

The GoToGuide for Valve Disease A helpful resource for patients and caregivers • Valve disease explained • Know the symptoms • Understanding treatment options • Recent FDA approval for expanded use of TAVR • What to expect during treatment Let’s Get Social Stay up to date on heart health and connect with Mended Hearts any time. Find us at www.mendedhearts.org and on these sites: facebook.com/mendedhearts facebook.com/MendedLittleHeartsNationalOrganization @MendedHearts @MLH_CHD Instagram.com/mendedlittleheartsnational The GoToGuide for Valve Disease Valve Disease Explained ..........................2 Know the Symptoms .............................. 8 Understanding Treatment Options ........9 Tools & Resources .................................. 18 Mended Hearts gratefully acknowledges the support of Edwards Lifesciences. mendedhearts.org The GoToGuide for Valve Disease 1 Valve Disease Explained What is Valve Disease? Heart disease is something we’ve all heard about, and for good reason: Right now, it’s the leading cause of death in the United States, killing more than 600,000 Americans every year. (That’s about one out of every four people.) One common form of heart disease is valve disease, which occurs when one or more of your heart valves isn’t working properly. Stenosis vs. Your heart has four valves — the tricuspid, Regurgitation pulmonary, mitral and aortic. Each of these When heart valves valves depends upon tissue flaps that open and become too close every time your heart beats. The flaps narrow for blood make sure blood flows in the right direction to pass through through your heart’s four chambers and to the efficiently, this is rest of your body. called stenosis. However, sometimes certain things interfere The narrowing is with how well the heart valves function. -

Mitral Valve Regurgitation

Sacramento Heart & Vascular Medical Associates February 19, 2012 500 University Ave. Sacramento, CA 95825 Page 1 916-830-2000 Fax: 916-830-2001 Patient Information For: Only A Test Mitral Valve Regurgitation What is mitral valve regurgitation? Mitral valve regurgitation is an abnormal, backwards flow of blood in the heart through the mitral valve. The mitral valve is 1 of 4 valves in the heart. It lies on the left side of the heart between the left upper chamber (atrium) and lower chamber (ventricle). The valve has 2 flaps called leaflets that normally close every time the ventricle squeezes to pump blood out of the heart. If the mitral valve does not close properly, some of the blood from the ventricle is forced back up (regurgitated) into the left atrium instead of flowing out to the rest of the body. The added workload on the heart and increased blood pressure in the lungs may eventually cause problems. How does it occur? Many things can damage the mitral valve and cause regurgitation. - Rheumatic fever can damage valve leaflets and cause scarring. The scars caused by this infection can deform the leaflets so that they don't close properly. - A condition called mitral valve prolapse can also cause mitral regurgitation. When you have mitral valve prolapse, one or both of the leaflets bulge (prolapse) into the atrium. A small amount of mitral regurgitation is common with mitral valve prolapse. - If one or more of the cordlike structures attaching the leaflets to the heart muscle breaks, the valve may leak. - Heart attacks, diseases of the heart muscle, or other heart valve problems may cause the heart to get bigger. -

Mitral Valve and Left Ventricular Features in Malignant Mitral Valve Prolapse

Open access Valvular heart disease Open Heart: first published as 10.1136/openhrt-2018-000925 on 15 October 2018. Downloaded from Mitral valve and left ventricular features in malignant mitral valve prolapse Madalina Garbi,1 Patrizio Lancellotti,2,3 Mary N Sheppard4 To cite: Garbi M, Lancellotti P, ABSTRACT Key questions Sheppard MN. Mitral valve and Objective Mitral valve prolapse is a benign condition, left ventricular features in however with occasional reports of sudden cardiac death malignant mitral valve prolapse What is already known about this subject? . or out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the absence of severe Open Heart 2018;5:e000925. ► Mitral valve prolapse is a benign condition, however mitral regurgitation or coronary artery disease, suggesting doi:10.1136/ with occasional reports of sudden cardiac death or the existence of a malignant form. The objective of openhrt-2018-000925 out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in the absence of se- our study was to contribute to the characterisation of vere mitral regurgitation or coronary artery disease, malignant mitral valve prolapse. suggesting the existence of a malignant form. Received 24 August 2018 Methods We performed a retrospective analysis of ► Sudden cardiac death is rare in mitral valve pro- Revised 4 September 2018 pathology findings in 68 consecutive cases of sudden lapse; however, the risk is twice as high as for the Accepted 26 September 2018 cardiac death with mitral valve prolapse as lone abnormal general population. finding, reported as cause of death. ► Characterisation of malignant mitral valve prolapse Results All mitral valve prolapse sudden death cases had is needed to underpin the selection of patients in mitral valve characteristics of Barlow disease, with extensive need of implantable cardioverter defibrillator for pri- bileaflet multisegmental prolapse and dilatation of the mary prevention. -

INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS—FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Return to Oral Health Topic: Infective Endocarditis • Where Can I Find

ORAL HEALTH TOPICS INFECTIVE ENDOCARDITIS—FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS Return to Oral Health Topic: Infective Endocarditis Where can I find information to hand out to patients? Do I need to confer with the patient’s physician before treating according to the guidelines? What if a patient insists he/she wants the premedication even though they no longer need it? Do patients with murmurs or mitral valve prolapse still require coverage? Do patients with stents require coverage? Do all patients with heart valve replacements, whether prosthetic, human or porcine, require premedication? Do patients who have had a mitral valve repaired with an annuloplasty ring require prophylaxis? My patient forgot to premedicate. What do I do? My patient is allergic to penicillin. What options do I have for premedication? My patient just had heart surgery. Does he or she require coverage? Do patients who have taken phen-fen need antibiotic prophylaxis? I have a patient who is already taking antibiotics. How does that affect the prophylactic regimen? Do the AHA updates affect the recommendations for patients with total joint replacements? Return to Top Where can I find information to hand out to patients? The ADA has information tailored to patients posted on ADA.org as well as a “For the Dental Patient” page that you may copy and give to your patients. In addition, the American Heart Association (AHA) has developed a downloadable wallet card , which summarizes this information for patients. Return to Top Do I need to confer with the patient’s physician before treating according to the guidelines? The courts recognize that each independent professional is responsible for his or her own treatment decisions. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse

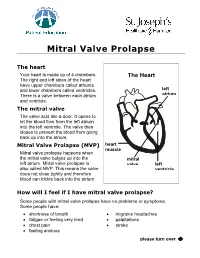

Mitral Valve Prolapse The heart Your heart is made up of 4 chambers. The Heart The right and left sides of the heart have upper chambers called atriums and lower chambers called ventricles. left There is a valve between each atrium atrium and ventricle. The mitral valve The valve acts like a door. It opens to let the blood flow from the left atrium into the left ventricle. The valve then closes to prevent the blood from going back up into the atrium. Mitral Valve Prolapse (MVP) heart muscle Mitral valve prolapse happens when the mitral valve bulges up into the mitral left atrium. Mitral valve prolapse is valve left also called MVP. This means the valve ventricle does not close tightly and therefore blood can trickle back into the atrium. How will I feel if I have mitral valve prolapse? Some people with mitral valve prolapse have no problems or symptoms. Some people have: • shortness of breath • migraine headaches • fatigue or feeling very tired • palpitations • chest pain • stroke • feeling anxious please turn over Î Mitral Valve Prolapse What causes mitral valve prolapse? We do not know why some people have mitral valve prolapse. We do know these facts: • Mitral valve prolapse can be caused by illnesses such as rheumatic fever, lupus, muscular dystrophy, or heart disease. • Mitral valve prolapse is found in men and women of all ages. • It is more common in women between 20 to 50 years old. • Mitral valve prolapse occurs in families. Let your doctor know if anyone in your family has MVP. How will the doctor know if I have mitral valve prolapse? Your doctor will listen to your heart with a stethoscope and hear an extra heart sound. -

Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome Volume 74, (Nº 5), 2000

França HH PointArq Bras de CardiolView Mitral valve prolapse syndrome volume 74, (nº 5), 2000 An Interpretation - Mitral Valve Prolapse Syndrome Hudson Hübner França Sorocaba, SP - Brazil Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) syndrome is a mechani- (spread) 22,23. Late potentials may exist 24,25. The literature cal phenomenon in which one or both of the mitral valve also reports cases of sudden death 19,26,27. leaflets move exaggeratedly during systole, upwards and These clinical manifestations associated with prolap- backwards, surpassing the valvar ring level (plane) 1-4 . This se constitute MVP syndrome. can happen under two circumstances, allowing its classifi- To date, these elements of MVP syndrome have not cation as either primary or secondary. had a convincing explanation. It is improbable that only the In secondary MVP, the leaflets are normal in dimension mechanical phenomena, the exaggerated movement of the and structure. However, due to several causes, the left ven- leaflets, can explain it 15,23. tricular cavity is smaller, diminished, or the papillary mus- Hypotheses have been thought of, for example the cles do not contract efficiently. exaggerated traction of the leaflets over the papillary mus- In the first case diminished left ventricular cavity the cles could cause ischemia and pain 17; the increased tension leaflets become proportionally larger in relation to the of the leaflet could deform, the atrioventricular groove chamber, which allows them to go upwards beyond the val- affecting the circumflex artery and producing ischemia 19. var level. It may happen, for example, in interatrial commu- Nervous terminals in the overly tensioned leaflets could nication. -

Floppy Valve Syndrome

REVIEW ARTICLE Am. J. PharmTech Res. 2018; 8(6) ISSN: 2249-3387 Journal home page: http://www.ajptr.com/ Floppy Valve Syndrome L. Siddhartha*, Sushma vuppala, Shravani Etrouth, Veda Sai Sri Gopalam Pulla Reddy Institute Of Pharmacy ABSTRACT Mitral valve prolapse is a valvular heart disease which results from the systolic movement of abnormally thickened mitral valve leaflets into left atrium during left ventricular systole. MVP refers to expansion of area of mitral valve leaflets with elongated chordae tendineae or rupture of chordae and mitral annular dilation. Rupture of chordae may be associated with heritable syndromes of connective tissue disorders. It usually inherited either through the autosomal dominant gene or chromosome X, which is less common compared to the former. MVP may lead to either progressive MVR or stimulate autonomic nervous system or neurohumoral activation. The former is termed as MVP and later is termed as “Floppy valve syndrome”. Symptoms of FVS include palpitations, dyspnea, chest pain, and neuropsychiatry symptom. Complications of FMV include infective endocarditis, Thromboembolic complications, systolic arterial hypertension, cardiac arrhythmias or cardiac death. Initially pharmacological agents are used as first line therapy. When severe mitral regurgitation is present in asymptomatic patient with FMV/MVP surgical intervention such as valve repair or valve replacement is recommended. Keywords: Mitral valve, FMV. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Received 01 October 2018, Accepted 17 November 2018 Please cite this article as: Siddhartha L et al., Floppy Valve Syndrome . American Journal of PharmTech Research 2018. Siddhartha et. al., Am. J. PharmTech Res. 2018; 8(6) ISSN: 2249-3387 INTRODUCTION “MITRAL VALVE SYNDROME” [MVP] is also known as, “Floppy mitral valve syndrome”, “Click murmur syndrome”, “Billowing mitral leaflet” or “Barlow syndrome”. -

Death in the Line of Duty... Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program

2010 05 Death in the line of duty... Fire Fighter Fatality Investigation and Prevention Program A summary of a NIOSH fire fighter fatality investigation June, 2010 Captain Dies After Extremely Heavy Physical Exertion at Building Fire from Complications of Mitral Valve Surgery– Kansas Executive Summary On December 13, 2009, a 51-year-old male career NIOSH investigators offer the following Captain responded to a fire in a condominium recommendations to address general safety and complex clubhouse. On scene while wearing full health issues. However, it is unlikely that any of turnout gear, he stretched a 2 1/2- and a 3-inch these recommendations could have prevented the hoseline and cut a hole in the building exterior Captain’s death. to access the crawl space. While in rehabilitation (rehab), the Captain experienced persistent Provide annual medical evaluations to all shortness of breath and palpitations/tachycardia. fire fighters consistent with National Fire These symptoms progressed over the next few Protection Association (NFPA) 1582, Standard days resulting in a subsequent diagnosis of mitral on Comprehensive Occupational Medical valve insufficiency/regurgitation. The Captain Program for Fire Departments. underwent surgery to repair his mitral valve on December 29, but suffered an intra-operative Discontinue routine pre-employment/ myocardial infarction (heart attack) from which preplacement exercise stress tests for he died 4 days later. The death certificate, applicants. completed by the pathologist, listed the cause of death as “massive acute myocardial infarction Ensure fire fighters are cleared for return to duty due to complications from mitral valve annulus by a physician knowledgeable about the physical placement due to severe mitral regurgitation demands of fire fighting, the personal protective aggravated by smoke/chemical inhalation.” The equipment used by fire fighters, and the various autopsy, completed by the pathologist, listed components of NFPA 1582.