University of the Witwatersrand

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

A1132-C270-001-Jpeg.Pdf

faJUtl&fp j y ^ V No. 4 ' Weekly Edition REPU^lC OF SOUTH AFRICA ^ HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY DEBATES (HAN S ARsQ) THIRD SESSION — THIRD PARLIAMENT 26th FEBRUARY to 1st MARCH, 1968 The sign * indicates that the speech was delivered in Afrikaans and then translated. Where both official languages are used in the same ministerial speech, t indicates the original and * the translated version. CONTENTS Stages of Bills taken without debate are not indicated below COL. NO. COL. NO. M onday, 26th February Births, Marriages and Deaths Registra tion Amendment Bill—Second Human Sciences Research Bill—Com Reading ............................................ 1220 mittee ............................................... 1119 Wine and Spirits Control Amendment Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amend Bill—Second Reading ..................... 1229 ment Bill—Third Reading .............. 1120 Bantu Administration by Local Authori Indians Advanced Technical Education ties—Motion .................................... 1231 Bill—Committee ............................. 1123 South African Indian Council Bill—Sec W ednesday, 28th F ebruary ond Reading.................................... 1124 Report of Commission of Enquiry into Wine. Other Fermented Beverages and Improper Political Interference and Spirits Amendment Bill—Second Political Representation of the Reading............................................ 1156 Various Population Group s— Waterval River (Lydenburg) Bill—Sec Motion ............................................. 1265 ond Reading ................................... -

Democracy Compromised Afrika-Studiecentrum Series

Democracy Compromised Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Editorial Board Prof. Nicolas van de Walle (Michigan State University, USA) Prof. Deborah Posel (Director WISER, South Africa) Dr Ruth Watson (University of London, UK) Dr Paul Mathieu (FAO, Rome) Dr Piet Konings (African Studies Centre) VOLUME 5 Democracy Compromised Chiefs and the politics of the land in South Africa by Lungisile Ntsebeza BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 Cover photo The office of the Ehlathini Tribal Authority in Xhalanga (photo by Melanie Alperstein) This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ntsebeza, Lungisile. Democracy compromised : chiefs and the politics of the land in South Africa / by Lungisile Ntsebeza. p. cm. — (Afrika-Studiecentrum series, ISSN 1570-9310 ; v. 5) Based on the author's doctoral thesis. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-14482-X (pbk.) 1. Chiefdoms—South Africa—Xalanga. 2. Tribal government—South Africa—Xalanga 3. Political customs and rites—South Africa--Xalanga. 4. Democracy—South Africa— Xalanga. 5. Xalanga (South Africa)—Politics and government. 6. Xalanga (South Africa)— Social conditions. I. Title. II. Series. GN656.N87 2005 320.968—dc22 2005047112 ISSN 1570–9310 ISBN 90 04 14482 X © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

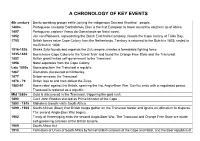

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire. -

The Rise and Decline of Urban Apartheid in South Africa Author(S): Paul Maylam Source: African Affairs, Vol

The Royal African Society The Rise and Decline of Urban Apartheid in South Africa Author(s): Paul Maylam Source: African Affairs, Vol. 89, No. 354 (Jan., 1990), pp. 57-84 Published by: Oxford University Press on behalf of The Royal African Society Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/722496 Accessed: 26/03/2010 06:11 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=oup. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Oxford University Press and The Royal African Society are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to African Affairs. http://www.jstor.org THE RISE AND DECLINE OF URBAN APARTHEID IN SOUTH AFRICA PAULMAYLAM IN DECEMBER1919 a deputation,representing the residentsof Ndabeni, an African township in Cape Town, met the Minister of Native Affairs to discuss the future of the township. -

The Sadf Conscript Generation and Its Search for Healing, Reconciliation and Social Justice

THE SADF CONSCRIPT GENERATION AND ITS SEARCH FOR HEALING, RECONCILIATION AND SOCIAL JUSTICE A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree Philosophiae Doctor in the Practical and Missional Theology department Faculty of Theology and Religion University of the Free State Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout Study leader: Prof. P. Verster Bloemfontein January 2015 Translated by Suzanne Storbeck (June 2020) DECLARATION (i) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that this thesis, submitted to the University of the Free State in fulfilment for the degree Philosophiae Doctor, is my own work and that it has not been handed in at any other university or higher education institution. (ii) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that I am aware that the copyright of this thesis belongs to the University of the Free State. (iii) I, Pieter Hendrik Schalk Bezuidenhout, declare that the property rights of any intellectual property developed during the study and/or in connection with the study, will be seated in the University of the Free State. i ABSTRACT The former (Afrikaner) SADF conscript generation is to a large extent experiencing an identity crisis. This crisis is due to two factors. First of all, there is a new dispensation where Afrikaners are a minority group. They feel alienated, even frustrated and confused. Secondly, their identity has been challenged and some would say defeated. What is their role and new identity in the current SA? They fought a war and participated internally in operations within a specific local, regional and global context. This identity was formed through their own particular history as well as certain theological and ideological worldviews and frameworks. -

[Lb4'il ,T>It?'/Lg D), C

I UN ARCHIVES I PLEASE RETAIN pRIGINAL ORDER SERIES <:., - C'« -4 (0 ul£tvt/ BOX ~ - . ~li (01 (UJoq FILE 5 j Ace. p~ 1/5:!I3 [lB4'IL ,t>It?'/lG d), C --c.-----------_ 2& _OF PQLltICI\t AWl) OONFIDi,NTIAL OOUNCIL AFFAIRS psc.A/PAD/bQ-22 "*,. 1960 BAOlGmUIDr PArE!-- -- - -- , 2! Tm gUESTIOI OF APlR1'1mlD INb THEUNIOJ-- -, 0'1 rom" MRICA I ~ BXSIORr UlXCIi.CJ' SCQIB~.D 1It1!'101 !r5(11__ ZldiifJ:M1 is' DDBIl'J ... • -:rift-- - - t - --- .___n__ .. __ 1. !'be f"tra\ ~~.. the Drdioh Ea.-t ID41a ~ a't 'the CI.pt r4 Ooccl Hope u 1652 la ~toeataWsh a 6Ipo'tot ~au tor ta ab1118 .'kIns ~ ND fIftII 'tbe ~~ 'to ~ Eat IDiI1u. J!fte aet'Ue:N 1IIIJ:e a11C1FsA to ..'bUsh 'lheule1W1t 1a 1671 to toeter 'tbe ~ c4 pronllioDa. Jlrca the begfmdng 'bbe ec1oJJ1 ..~Uti! prolWmll or relaUma 91:th the Batten'tat aDil Baalam ~ ia ... i&ft18 aDd 800Il Vi'th ~ c:4 a ~ng hB1.t.-ate pa,pu1aUcmo 20' ~ 1678 lmtU 1'107 :t_araUcn .. aetl~ ~j 8D4 aet'Ue:N of Date'h$ aer.m aDd ~ eztract1Cl11 __ ~ D .... c:~:t1ea<> ~ a. a :reau3;\; of d1ffl.eul'tl_ with the ~., tIbe ~ .eJ!1d84 tbl. pol1q ill 1107, aDd ~ tba't tiM mrbU.1:lIe Br:ltta a~"lon otthe cape t.hez'e ._ pract1ca1:b' DO ~ tMlsraUca. In 1TlO ..'tt. t1ftt ltoer ccrrtIaetV1th Irm'tu 'tribu on ...ftab MYel' __ ItAa' ~ Id.Jea eaR· c4 ca~9 I1l 1m, after 7fJ8ftI or ..,laUltll .~m1IIru1e bJ' CatplI-.r oftle1a1a, tht la~ 1IID"a 4ri.'ftZ'1 me;,. -

FAGAN REPORT.Pdf

't I i,t ERRAT.*. P. 2. Tronspose lines 20 cnd 2l in {irst porogtoph. P. 13. 4lh line - Ior "weory" reod "wory". P. 14- 6th lin€i - olter "Iorm" delete "that". 9th line - {or "complyment" read "complicnce". P. 25. 25th line - Ior "in deteriorcting" reod "is deteriorqting I Thoughts on Relations" I A limited redition of three Hoernl6 Lectures containing will thoAe who wish to order please write to: I The Editor," l S.A. Institute of Race Relations, 1 Box 97, Johannesburg- ) I I l I l Donaldson Blueprmt Series No. 1. o A DIGEST OF THE NATIVE LAWS (FAGAN) COMMISSION (Prepcred by Helen Suzmqn) A DIGEST of the 1947 11948 BROOME COMMISSION (Prepcred by Mcrurice Webb) "One of the moin objections to the Notive Lcws Conmission Report is thot those who hove crilicised it most bitterly hove not reod it. Thot meons 99 I per cent of the Europeon populotion in South Africo." i\4r. Justice H. A. Fogon, Cope Town, July 13th, 1946 SOUTH AF]]ICAN INSTITUTE OF RACE RELATIONS P.O. BOX 97. ]OHANNESBURG. Modei Printing Co 7- This d,igest of the Natiue Luws Comm'issioru is the lirst in d, llew Bluepri,nt saries beuring the nam'e of CoL James Donaldson, D.S.O., It lt'us been mq'd,e possible by tlte generos'ity of the Bantu We'ufnre Trust founded bu Col. Dotlulclsoru countrg. \ D IG EST OF TH E FAGAN REPORT rll HE Native Laws Commission under the chairmanship I of Mr. Justice H. A. Fagan, K.C., was appointed by the Government in August, L946, with the following terms of rgfgvsnsg;- To enquire into and report upon- (a) The operation of the laws in force in the -

Class of Their Own: the Bantu Education Act (1953) Revisited

IN A CLASS OF THEIR OWN: THE BANTU EDUCATION ACT (1953) REVISITED. by NADINE LAUREN MOORE Submitted as requirement for the degree MAGISTER HEREDITATIS CULTURAEQUE SCIENTIAE (HISTORY) in the Faculty of Humanities University of Pretoria Pretoria 2015 Supervisor: Professor Karen L. Harris Abstract Various political parties, civil rights groups, ministerial spokespeople and columnists support the view that one of South Africa's leading challenges is overcoming the scarring legacy that the Bantu Education Act of 1953 left on the face of the country. In the light of this a need arises to revisit the position and place of Bantu Education in the current contested interpretation of its legacy. It is apparent from the vast literature on this topic that academics are not in agreement about whether or not the 1953 education legislation was the watershed moment for ensuring a cheap labour force. On the one hand it would seem that the general consensus is that 1953 was indeed a turning point in this regard – thus a largely traditional view. However, on the other hand, another school of thought becomes apparent, which states that securing a cheap, unskilled labour force was already on the agenda of the white electorate preceding the formalisation of the Bantu Education Act. This latter school of academics propose that their theory be coined as a “Marxist” one. In examining these two platforms of understanding, traditional and Marxist, regarding Bantu Education and the presumption that it was used as a tool to ensure a cheap, unskilled labour force, the aim of this study is two-fold. First, to contextualise these two stances historically; and second to examine the varying approaches regarding the rationalisation behind Bantu Education respectively by testing these against the rationale apparent in the architects of the Bantu Education system. -

I Iiibiiw1>Tf 1

~[( ~/I,1I/ (~ 7JLc.:t-- n Ift-s f) flu I JC'I"']) t? 1'7 H 'll I> k j 1(···/ ~ t.-~ 6V~ lA~ A:.f~ 11 lfVl dJ Aiyr - P En-h -I LeA !' AYJ er{./.r-tt-:J' tid £-t.tvt {. I t'r..... II PLEASE RET.AIN ORIGINl\.L OItDEI{ uN ARCHIVES Uuvv SERIES j-o''(ll''-p ~ I Ii IbIIW1>tf 1 BOX -- FILE _~__ 0l-~4-L ACC.P/1~4/5-,J6 -t,'J~' JI- 6). G Confidential 20 July 1960 Copy No. J.(E"'9 APARTHEID IN SOU TH AFRICA APARTHEID IN SOUTH AFRICA INDEX Page No. LAND AND PEOPLE •.•••••••••••••••••••••••••••••.. 1-3 II. HISTORY ••••••••••••••.•.••••••••••••••••.•••.••• 4-13 III. SYSTEM OF GQVERNMENT ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 14-17 IV" GENERAL OUTLINE OF.' APARTHEID . 18-22 V. DETAILED MFASURES OF APARTHEID AND THEIR IMPLEVWNTATION o.~~oo.ooooO.O ••• 'O ••• O 23-43 (a) Promotion of Bantu Self-Government •......... 23-27 (b) Economic and Social Development of the Bantu Areas •••••••••••••••••••••••• 28-31 (c) Bantu Educational Development ••••••••••••••• 31-33 (d) The Position of Natives in Urban Areas •••••• 33-38 (e) Separate Group Areas . 38-39 (r) Other Curtailments of Inter-Racial Contact in Urban Areas ••••••••••••••••••• 39-40 (g) Population Registration and Identity Cards ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40 (h) Labour Organization ••••••••••••••••••••••••• 40-41 (i) Civil Liberties ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 41-42 (j) Limitation of the Authority of Courts ••••••• 42-43 VI. POLITICAL PARTIES AND ORGANIZATIONS . 44-63 (a) Introduction •••••• 0 ••••• •• ••••••• •• ••••••••• 44-45 (b) The National Party •••••••••••••••••••••••••• 45-46 (e) The United Party . 46-47 (d) The Progressive Party ••••••••••••••••••••••• 47-50 (e) The Minor Parties ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 51-53 (f) Other Organizations of the White Population • 53-55 (g) Obstacles to Non-White Political Activities 55-57 (h) African Political Organizations ••••••••••••• 57-61 (i) Organizations among the "ColouredII Population •••••••••••••••••••••••.•••••• 61-62 (j) Organizations of Population of Indian Origin ••••••••••••••••••••••••••• 62-63 VII. -

The United Party's "New" Native Policy

NOT FOR PUBLICATION. INSTITUTE OF CURRENT WORLD AFFAIRS c/o J. M. Penniron The United Party's 5, Elm Sret, "New" Native Policy Houghton, Johannesbur December 29, 195 Mr. Walter S. Rogers Institute of Ourrent World Affairs 522 Fifth Avenue, New York 6, New York Dear Mr. Rogers "Alice never could quite make out, in thinkin it over afterwards, how it was that they began: all she remembers is, that they were running hand in hand, and the Queen went so fast that it was all she could do to keep up with her and still the Queen kept cryir 'Faster! Faster:' but Alice felt she coul__d no__t faster, though she had no breath left to say so. "The most curious part of the thin was, that the trees and the other thins round them never changed their places at all: however fast they went, they never seemed to pass anything. 'I wonder if all the things move along with us?' thought poor puzzled Alice. And the Queen seemed to guess her thoughts, for she cried 'Faster: Don't try to talk!' ". 'Now Now'.' cried the Queen. 'Faster FesterS. And they went so fast that at last they seemed to skim through the air, hardly touchin the ground with their feet, till suddenly, Just as Alice was getting quite exhausted, they stopped, and she found herself sittin on the ground, breathless and iddy. "The Queen propped her up against a tree, and said kindly, 'You may rest a little, now, "Alice looked round her in great surprise. Why, I do believe weve been under this tree the whole time Everything's just as it was. -

The Smuts Go- and the Africans, 1939-48

THE SMUTS GO- AND THE AFRICANS, 1939-48 by I.R. K. Davenport The United Party rump which entered into power in September 1939 inherited a policy for race relations which derived directly from the Hertzog legislation of 1976-37, with no apparent intention of changing it. The Hertzog recipe was cooked in a three-legged pot: one leg was the communal representation of the African voters of the Cape on a separate roll; the secwad was the territorial segregation of Africans in their own Reserves; and the khird was the segregation of urban Africans and the limitation of their ~vmnbersin accordance with the availability of work in a.ny particular town (essen.tially the gospel of Colonel Stallard, which Hertzog seems to have taken over). mere the Cape Coloured people were concerned, Hertzog's policy was in %he process of formation, ar,d its lines not yet rigid: his political and ecs~cmit:"new deal" had been a casualty of the debates of 1926-36, and although Giie Willcocks Commission reported in 1937, urgjag that Vie Coloured people merited better jobs, better trade unions, better schools, better health servicea an.& pensions, more opportunities for owning land and a chance to learn how to farm it, and even a parliamentary vote in the northerri provinces if they were highly qualified, no legislation followed before Hertzog fell from power. This was almost certainly because he was having a lot of difficulty with his own rank and file. Ln the case of the Indian populations of Natal and the Transvaal, the voluntary repatriation agreed on in Cape Town between the Lndiain and South African governments in 1927 had not produced the results anticipated by both parties, and by the mid-1930s there were signs of renewed pressure on the &dim community of both provinces.