Social Citizenship and the Transformations of Wage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2021 “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael R. Hogan West Virginia University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Part of the African History Commons Recommended Citation Hogan, Michael R., "“Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962" (2021). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8264. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8264 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Remov[e] Us From the Bondage of South Africa:” Transnational Resistance Strategies and Subnational Concessions in Namibia's Police Zone, 1919-1962 Michael Robert Hogan Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy In History Robert M. -

Click Here to Download

The Project Gutenberg EBook of South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I, by J. Castell Hopkins and Murat Halstead This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: South Africa and the Boer-British War, Volume I Comprising a History of South Africa and its people, including the war of 1899 and 1900 Author: J. Castell Hopkins Murat Halstead Release Date: December 1, 2012 [EBook #41521] Language: English *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK SOUTH AFRICA AND BOER-BRITISH WAR *** Produced by Al Haines JOSEPH CHAMBERLAIN, Colonial Secretary of England. PAUL KRUGER, President of the South African Republic. (Photo from Duffus Bros.) South Africa AND The Boer-British War COMPRISING A HISTORY OF SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS PEOPLE, INCLUDING THE WAR OF 1899 AND 1900 BY J. CASTELL HOPKINS, F.S.S. Author of The Life and Works of Mr. Gladstone; Queen Victoria, Her Life and Reign; The Sword of Islam, or Annals of Turkish Power; Life and Work of Sir John Thompson. Editor of "Canada; An Encyclopedia," in six volumes. AND MURAT HALSTEAD Formerly Editor of the Cincinnati "Commercial Gazette," and the Brooklyn "Standard-Union." Author of The Story of Cuba; Life of William McKinley; The Story of the Philippines; The History of American Expansion; The History of the Spanish-American War; Our New Possessions, and The Life and Achievements of Admiral Dewey, etc., etc. -

University of the Witwatersrand

UNIVERSITY OF THE WITWATERSRAND AFRICAN STUDIES INSTITUTE African Studies Seminar Paper to be presented in RW 4.00pm MARCH 1976 Title: Liberalism and Ethnicity in South African Politics, 1921-1948 by: Paul Rich No. 040 Liberalism and ethnicity in South African politics. 1921-1948 One of the main problems confronting liberal ideology in the South African context is the nature and role of group identities. This has been no small question because liberal theorists have tended to be hide-bound by a reliance on the inherent rationality of a free market that specifically excludes the role of group interests from its sphere of operations. Thus, while twentieth century liberalism has made a number of important revisions in the classical laissez-faire model of the nineteenth century (I), it still places a considerable emphasis on the free market sector even though, as Professor John Kenneth Galbraith has observed, this now typifies only a minority sector in western capitalist economies (2). It is this dependency on the free- market model, however, that restricts the liberal view of rationality to one of economics. The most rational figure in this view remains the classic homo economicus. the child of the Eighteenth Century Enlightenment, who buys in the cheapest market and sells in the dearest. The implications of this model are far-reaching in terms of J social values. If the basis of society is seen to rest on free- floating individuals motivated by a high degree of psychological hedonism then the basis of society's values rests on individual ones to the neglect of the wider community. -

Throughout the 1950S the Liberal Party of South Africa Suffered Severe Internal Conflict Over Basic Issues of Policy and Strategy

Throughout the 1950s the Liberal Party of South Africa suffered severe internal conflict over basic issues of policy and strategy. On one level this stemmed from the internal dynamics of a small party unequally divided between the Cape, Transvaal and Natal, in terms of membership, racial composftion and political traditon. This paper and the larger work from which it is taken , however, argue inter alia that the conflict stemmed to a greater degree from a more fundamental problem, namely differing interpretations of liberalism and thus of the role of South African liberals held by various elements within the Liberal Party (LP). This paper analyses the political creed of those parliamentary and other liberals who became the early leaders of the LP. Their standpoint developed in specific circumstances during the period 1947-1950, and reflected opposition to increasingly radical black political opinion and activity, and retreat before the unfolding of apartheid after 1948. This particular brand of liberalism was marked by a rejection of extra- parliamentary activity, by a complete rejection of the univensal franchise, and by anti-communism - the negative cgaracteristics of the early LP, but also the areas of most conflict within the party. The liberals under study - including the Ballingers, Donald Molteno, Leo Marquard, and others - were all prominent figures. All became early leaders of the Liberal Party in 1953, but had to be *Ihijackedffigto the LP by having their names published in advance of the party being launched. The strategic prejudices of a small group of parliamentarians, developed in the 1940s, were thus to a large degree grafted on to non-racial opposition politics in the 1950s through an alliance with a younger generation of anti-Nationalists in the LP. -

Tusxegee, the Joint Councils, and the All Aprican Convention

TUSXEGEE, THE JOINT COUNCILS, AND THE ALL APRICAN CONVENTION by Baruch Hirson In June 1936 Heaton Nicholls, Member of Parliament for Zululand, asad member of the Native Affairs Commission (NAC), launched an attack on the Joint Councils of Europeans and Natives for llcarryingon intensive propagandat' and taking Ifthe political stage in attacking the measure before the Committee [stage of the Nztive Billsltq.((L) Nicholls was inCen.sed and charged that: It was the Joint Councils which organised the Bloemfontein Conference of Natives. They organised the whole of this agitation throughout the whole of .the country ... What is the difference between a Communist propagandist who believes that human happiness can be better furthered if people will only adopt his tenets, and the bishops and the judges who go around the country telling the Natives that if they will only join together and witate sufficiently, and believe that Parliament is animated by the worst possible repressive intentions they will be the happier for it. (2) W. H. Ramsbottom, chairman of the Johannesburg Joint Council, in a reply to Nicholls wmte to all members of parliament ayld to the press deqying the accusation. He stated that the Joint Councils had declared against the Native Bills in 1927 but thereafter had waited for the outcome of the deliberations of successive Committees appointed by Parliament. He claimed that his Council had acted with the U-tmost decorum and had been silent while the issue went before the Select Committee of the House, and had withheld all comment for over six months, to give the Secretary for Native Affairs and members of the NAC time to tour South Africa explaining the Bills to Native leaders. -

A1132-C270-001-Jpeg.Pdf

faJUtl&fp j y ^ V No. 4 ' Weekly Edition REPU^lC OF SOUTH AFRICA ^ HOUSE OF ASSEMBLY DEBATES (HAN S ARsQ) THIRD SESSION — THIRD PARLIAMENT 26th FEBRUARY to 1st MARCH, 1968 The sign * indicates that the speech was delivered in Afrikaans and then translated. Where both official languages are used in the same ministerial speech, t indicates the original and * the translated version. CONTENTS Stages of Bills taken without debate are not indicated below COL. NO. COL. NO. M onday, 26th February Births, Marriages and Deaths Registra tion Amendment Bill—Second Human Sciences Research Bill—Com Reading ............................................ 1220 mittee ............................................... 1119 Wine and Spirits Control Amendment Prohibition of Mixed Marriages Amend Bill—Second Reading ..................... 1229 ment Bill—Third Reading .............. 1120 Bantu Administration by Local Authori Indians Advanced Technical Education ties—Motion .................................... 1231 Bill—Committee ............................. 1123 South African Indian Council Bill—Sec W ednesday, 28th F ebruary ond Reading.................................... 1124 Report of Commission of Enquiry into Wine. Other Fermented Beverages and Improper Political Interference and Spirits Amendment Bill—Second Political Representation of the Reading............................................ 1156 Various Population Group s— Waterval River (Lydenburg) Bill—Sec Motion ............................................. 1265 ond Reading ................................... -

Ÿþm Icrosoft W

Chapter Two Chapter Two BLACK ORGANISATIONS EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL GROUPS ASSOCIATION FOR THE EDUCATIONAL AND CULTURAL ADVANCEMENT OF AFRICAN PEOPLE OF SOUTH AFRICA (ASSECA) Background ASSECA WAS ESTABLISHED in 1967 through the efforts of the late Mr P.Q. Vundla and Mr M.T. Moerane. Initially Asseca was designed to operate mainly in the Reef area but the leadership soon saw the need for such an organisation to be established on a national basis. Asseca operates on a city/town branch basis. According to reports tabled at the 1972 Asseca Conference, the organisation has 19 branches in the Transvaal, Orange Free State, Eastern Cape and Western Cape whilst new branches are in the process of being formed in Natal. Each year these branches send delegates to a conference *which is the supreme policymaking organ for Asseca. The Conference elects an Executive of 9 members. The present Executive is headed by Mr M.T. Moerane as President. Activities In 1972 Asseca consolidated its drive to interest African people in the education of their children. A point by point account of the work done by Asseca in this field is dealt with in the chapter on Primary and Secondary Education (see Chapter 8). One of Asseca's goals is the establishment of a R 1 million fund for Educational and Cultural groups scholarships for African children. Although, according to some reports, not many scholarships were given at the beginning of the year, the 1972 Asseca Conference decided to give a total of 100 bursaries to each branch at R20 per scholarship. This is regarded as an interim measure whilst the R I million fund is being built up. -

South African Jewish Board of Deputies Report of The

The South African Jewish Board of Deputies JL 1r REPORT of the Executive Council for the period July 1st, 1933, to April 30th, 1935. To be submitted to the Eleventh Congress at Johannesburg, May 19th and 20th, 1935. <י .H.W.V. 8. Co י É> S . 0 5 Americanist Commiitae LIBRARY 1 South African Jewish Board of Deputies. EXECUTIVE COUNCIL. President : Hirsch Hillman, Johannesburg. Vice-President» : S. Raphaely, Johannesburg. Morris Alexander, K.C., M.P., Cape Town. H. Moss-Morris, Durban. J. Philips, Bloemfontein. Hon. Treasurer: Dr. Max Greenberg. Members of Executive Council: B. Alexander. J. Alexander. J. H. Barnett. Harry Carter, M.P.C. Prof. Dr. S. Herbert Frankel. G. A. Friendly. Dr. H. Gluckman. J. Jackson. H. Katzenellenbogen. The Chief Rabbi, Prof. Dr. j. L. Landau, M.A., Ph.D. ^ C. Lyons. ^ H. H. Morris Esq., K.C. ^י. .B. L. Pencharz A. Schauder. ^ Dr. E. B. Woolff, M.P.C. V 2 CONSTITUENT BODIES. The Board's Constituent Bodies are as. follows :— JOHANNESBURG (Transvaal). 1. Anykster Sick Benefit and Benevolent Society. 2. Agoodas Achim Society. 3. Beth Hamedrash Hagodel. 4. Berea Hebrew Congregation. 5. Bertrams Hebrew Congregation. 6. Braamfontein Hebrew Congregation. 7. Chassidim Congregation. 8. Club of Polish Jews. 9. Doornfontein Hebrew:: Congregation.^;7 10. Eastern Hebrew Benevolent Society. 11. Fordsburg Hebrew Congregation. 12. Grodno Sifck Benefit and Benevolent Society. 13. Habonim. 14. Hatechiya Organisation. 15. H.O.D. Dr. Herzl Lodge. 16. H.O.D. Sir Moses Montefiore Lodge. 17. Jeppes Hebrew Congregation, 18. Johannesburg Jewish Guild. 19. Johannesburg Jewish Helping Hand and Burial Society. -

By John Lazar Balllol College Oxford University Michaelmas Term, 1987

CONFORMITY AND CONFLICT: AFRIKANER NATIONALIST POLITICS IN SOUTH AFRICA, 1948-1961 by John Lazar Balllol College Oxford University Michaelmas Term, 1987 One of the principal themes of this thesis is that it is incorrect to treat M Afrikanerdom" as a monolithic, unified ethnic entity. At the time of its election victory in 1948, the National Party (NP) represented an alliance of various factions and classes, all of whom perceived their Interests in different ways. Given, too, that black resistance to exploitation and oppression increased throughout the 1950s, apartheid ideology cannot be viewed as an immutable, uncontested blueprint, which was stamped by the NP on to a static political situation. The thesis is based on four main strands of research. It is grounded, firstly, in a detailed analysis of Afrikaner social stratification during the 1950s. The political implications of the rapid increase in the number of Afrikaners employed in "white-collar" occupations, and the swift economic expansion of the large Afrikaner corporations, are also examined. The second strand of research examines the short-term political problems which faced the nationalist alliance in the years following its slim victory in the 1948 election. Much of the NP's energy during its first five years in office was spent on consolidating its precarious hold on power, rather than on the imposition of a "grand" ideological programme. Simultaneously, however, intense discussions - and conflicts - concerning the long-term implications, goals and justifications of apartheid were taking place amongst Afrikaner intellectuals and clergymen. A third thrust of the thesis will be to examine the way in which these conflicts concretely shaped the ultimate direction of apartheid policy and ideology. -

EDITORIAL Re-Fighting the 2Nd Anglo-Boer War: Historians

http://scientiamilitaria.journals.ac.za EDITORIAL Re-fighting the 2nd Anglo-Boer War: historians in the trenches nd Some one hundred years ago, South Africa was tom apart by the 2 Anglo- Boer War (1899-1902). The war was a colossal psychological experience fought at great expense: It cost Britain twenty-two thousand men anti £223 million. The social, economic and political cost to South Africa was greater than the statistics immediately indicate: at least ten thousand fighting men in addition to the camp deaths, where a combination of indifference and incompetence resulted in the deaths of 27 927 Boers and at least 14 154 Black South Africans. Yet these numbers belie the consequences. It was easy for the British to 'forget' the pain of the war, which seemed so insignificant after the losses sustained in 1914-18. With a long history of far-off battles and foreign wars, the British casualties of the Anglo-Boer War became increasingly insignificant as opposed to the lesser numbers held in the collective Afrikaner mind. This impact may be stated somewhat more candidly in terms of the war participation ratio for the belligerent populations. After all, not all South Africans fought in uniform. For the Australian colonies these varied between 4Y2 per thousand (New South Wales) to 42.3 per thousand (Tasmania). New Zealand 8 per thousand, Britain 8Y2 per thousand: and Canada 12.3 per thousand; while in parts of South Africa this was perhaps as high as 900 per thousand. The deaths and high South African participation ratio, together with the unjustness of the war in the eyes of most Afrikaners, introduced bitterness, if not a hatred, which has cast long shadows upon twentieth-century South Africa. -

Democracy Compromised Afrika-Studiecentrum Series

Democracy Compromised Afrika-Studiecentrum Series Editorial Board Prof. Nicolas van de Walle (Michigan State University, USA) Prof. Deborah Posel (Director WISER, South Africa) Dr Ruth Watson (University of London, UK) Dr Paul Mathieu (FAO, Rome) Dr Piet Konings (African Studies Centre) VOLUME 5 Democracy Compromised Chiefs and the politics of the land in South Africa by Lungisile Ntsebeza BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 Cover photo The office of the Ehlathini Tribal Authority in Xhalanga (photo by Melanie Alperstein) This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ntsebeza, Lungisile. Democracy compromised : chiefs and the politics of the land in South Africa / by Lungisile Ntsebeza. p. cm. — (Afrika-Studiecentrum series, ISSN 1570-9310 ; v. 5) Based on the author's doctoral thesis. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 90-04-14482-X (pbk.) 1. Chiefdoms—South Africa—Xalanga. 2. Tribal government—South Africa—Xalanga 3. Political customs and rites—South Africa--Xalanga. 4. Democracy—South Africa— Xalanga. 5. Xalanga (South Africa)—Politics and government. 6. Xalanga (South Africa)— Social conditions. I. Title. II. Series. GN656.N87 2005 320.968—dc22 2005047112 ISSN 1570–9310 ISBN 90 04 14482 X © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Brill provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910 Danvers, MA 01923, USA. -

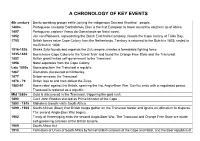

A Chronology of Key Events

A CHRONOLOGY OF KEY EVENTS 4th century Bantu speaking groups settle, joining the indigenous San and Khoikhoi people. 1480s Portuguese navigator Bartholomeu Dias is the first European to travel round the southern tip of Africa. 1497 Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama lands on Natal coast. 1652 Jan van Riebeeck, representing the Dutch East India Company, founds the Cape Colony at Table Bay. 1795 British forces seize Cape Colony from the Netherlands. Territory is returned to the Dutch in 1803; ceded to the British in 1806. 1816-1826 Shaka Zulu founds and expands the Zulu empire, creates a formidable fighting force. 1835-1840 Boers leave Cape Colony in the 'Great Trek' and found the Orange Free State and the Transvaal. 1852 British grant limited self-government to the Transvaal. 1856 Natal separates from the Cape Colony. Late 1850s Boers proclaim the Transvaal a republic. 1867 Diamonds discovered at Kimberley. 1877 Britain annexes the Transvaal. 1878 - 79 British lose to and then defeat the Zulus 1880-81 Boers rebel against the British, sparking the first Anglo-Boer War. Conflict ends with a negotiated peace. Transvaal is restored as a republic. Mid 1880s Gold is discovered in the Transvaal, triggering the gold rush. 1890 Cecil John Rhodes elected as Prime Minister of the Cape 1893 - 1915 Mahatma Gandhi visits South Africa 1899 - 1902 South African (Boer) War British troops gather on the Transvaal border and ignore an ultimatum to disperse. The second Anglo-Boer War begins. 1902 Treaty of Vereeniging ends the second Anglo-Boer War. The Transvaal and Orange Free State are made self-governing colonies of the British Empire.