The Ukraine and the Dialectics of Nation-Building Author(S): Omeljan Pritsak and John S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annoucements of Conducting Procurement Procedures

Bulletin No�24(98) June 12, 2012 Annoucements of conducting 13443 Ministry of Health of Ukraine procurement procedures 7 Hrushevskoho St., 01601 Kyiv Chervatiuk Volodymyr Viktorovych tel.: (044) 253–26–08; 13431 National Children’s Specialized Hospital e–mail: [email protected] “Okhmatdyt” of the Ministry of Health of Ukraine Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: 28/1 Chornovola St., 01135 Kyiv www.tender.me.gov.ua Povorozniuk Volodymyr Stepanovych Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications (Imiglucerase in flasks, tel.: (044) 236–30–05 400 units), 319 pcs. Website of the Authorized agency which contains information on procurement: Supply/execution: 29 Berezniakivska St., 02098 Kyiv; during 2012 www.tender.me.gov.ua Procurement procedure: open tender Procurement subject: code 24.42.1 – medications, 72 lots Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, office 138 Supply/execution: at the customer’s address; July – December 2012 Submission: at the customer’s address, office 138 Procurement procedure: open tender 29.06.2012 10:00 Obtaining of competitive bidding documents: at the customer’s address, Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office 138 economics department 29.06.2012 12:00 Submission: at the customer’s address, economics department Tender security: bank guarantee, deposit, UAH 260000 26.06.2012 10:00 Terms of submission: 90 days; not returned according to part 3, article 24 of the Opening of tenders: at the customer’s address, office of the deputy general Law on Public Procurement director of economic issues Additional information: For additional information, please, call at 26.06.2012 11:00 tel.: (044) 253–26–08, 226–20–86. -

142-2019 Yukhnovskyi.Indd

Original Paper Journal of Forest Science, 66, 2020 (6): 252–263 https://doi.org/10.17221/142/2019-JFS Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study Vasyl Yukhnovskyi1*, Olha Zibtseva2 1Department of Forests Restoration and Meliorations, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv 2Department of Landscape Architecture and Phytodesign, Forest Institute, National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, Kyiv *Corresponding author: [email protected] Citation: Yukhnovskyi V., Zibtseva O. (2020): Green space trends in small towns of Kyiv region according to EOS Land Viewer – a case study. J. For. Sci., 66: 252–263. Abstract: The state of ecological balance of cities is determined by the analysis of the qualitative composition of green space. The lack of green space inventory in small towns in the Kyiv region has prompted the use of express analysis provided by the EOS Land Viewer platform, which allows obtaining an instantaneous distribution of the urban and suburban territories by a number of vegetative indices and in recent years – by scene classification. The purpose of the study is to determine the current state and dynamics of the ratio of vegetation and built-up cover of the territories of small towns in Kyiv region with establishing the rating of towns by eco-balance of territories. The distribution of the territory of small towns by the most common vegetation index NDVI, as well as by S AVI, which is more suitable for areas with vegetation coverage of less than 30%, has been monitored. -

1 Introduction

State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES For map and other editors For international use Ukraine Kyiv “Kartographia” 2011 TOPONYMIC GUIDELINES FOR MAP AND OTHER EDITORS, FOR INTERNATIONAL USE UKRAINE State Service of Geodesy, Cartography and Cadastre State Scientific Production Enterprise “Kartographia” ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Prepared by Nina Syvak, Valerii Ponomarenko, Olha Khodzinska, Iryna Lakeichuk Scientific Consultant Iryna Rudenko Reviewed by Nataliia Kizilowa Translated by Olha Khodzinska Editor Lesia Veklych ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ © Kartographia, 2011 ISBN 978-966-475-839-7 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 Introduction ................................................................ 5 2 The Ukrainian Language............................................ 5 2.1 General Remarks.............................................. 5 2.2 The Ukrainian Alphabet and Romanization of the Ukrainian Alphabet ............................... 6 2.3 Pronunciation of Ukrainian Geographical Names............................................................... 9 2.4 Stress .............................................................. 11 3 Spelling Rules for the Ukrainian Geographical Names....................................................................... 11 4 Spelling of Generic Terms ....................................... 13 5 Place Names in Minority Languages -

Scandinavian Influence in Kievan Rus

Katie Lane HST 499 Spring 2005 VIKINGS IN THE EAST: SCANDINAVIAN INFLUENCE IN KIEVAN RUS The Vikings, referred to as Varangians in Eastern Europe, were known throughout Europe as traders and raiders, and perhaps the creators or instigators of the first organized Russian state: Kievan Rus. It is the intention of this paper to explore the evidence of the Viking or Varangian presence in Kievan Rus, more specifically the areas that are now the Ukraine and Western Russia. There is not an argument over whether the Vikings were present in the region, but rather over the effect their presence had on the native Slavic people and their government. This paper will explore and explain the research of several scholars, who generally ascribe to one of the rival Norman and Anti- Norman Theories, as well as looking at the evidence that appears in the Russian Primary Chronicle, some of the laws in place in the eleventh century, and two of the Icelandic Sagas that take place in modern Russia. The state of Kievan Rus was the dominant political entity in the modern country the Ukraine and western Russia beginning in the tenth century and lasting until Ivan IV's death in 1584.1 The region "extended from Novgorod on the Volkhov River southward across the divide where the Volga, the West Dvina, and the Dnieper Rivers all had their origins, and down the Dnieper just past Kiev."2 It was during this period that the Slavs of the region converted to Christianity, under the ruler Vladimir in 988 C.E.3 The princes that ruled Kievan Rus collected tribute from the Slavic people in the form of local products, which were then traded in the foreign markets, as Janet Martin explains: "The Lane/ 2 fur, wax, and honey that the princes collected from the Slav tribes had limited domestic use. -

Omelyan Pritsak: in Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Yaroslav Kalakura*

Journal of International Eastern European Studies/Uluslararası Doğu Avrupa Araştırmaları Dergisi, Vol./Yıl. 1, No/Sayı. 1, Summer/Yaz 2019) ISSN: 2687-3346 Omelyan Pritsak: In Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Yaroslav Kalakura* (Article Sent on: 10.06.2019/ Article Accepted on: 05.08.2019) Abstract It’s highlighted the role of Academician Omeljan Pritsak in the revival of historiography and historiosophy at the Taras Shevchenko University of Kyiv, his contribution to the methodological and theoretical reorientation of post- Soviet historians of Ukraine. They considered on the basis of works of predecessors, own studios, observations and personal memories of communication with scientists, his idea and the concept of the founding of the first on the post-Soviet space of the historiosophical chair, formation of its composition, elaboration of the educational-professional program, problems of lectures and seminars. The unique combination of the scientific work of O. Pritsak and his pedagogical skills is revealed, it was emphasized that the lectures of the scientist were content-rich and methodically perfect, they paid much attention to the works of G. Hegel "Philosophy of History", the views of F. Savigny, Leopold Ranke, leaders of the French school Annals of Mark Blok and Lucien Fever, their follower Fernand Braudel, analysis of the positivist doctrine of Auguste Comte, neo-Kantianism, modernism, instrumentalism, uniqueness of approaches to the history of supporters of the civilizational understanding of history O. Spengler and O. Toynbee. The atmosphere of high activity and recklessness was marked by historiosophical seminars, turning into lively scientific discussions, interesting and sharp polemics on the basis of reports prepared by their participants, abstracts. -

Contributions by Canadian Social Scientists to the Study of Soviet Ukraine During the Cold War

Contributions by Canadian Social Scientists to the Study of Soviet Ukraine During the Cold War Bohdan Harasymiw University of Calgary Abstract: This article surveys major publications concerning Ukraine by Canadian social scientists of the Cold War era. While the USSR existed, characterized by the uniformity of its political, economic, social, and cultural order, there was little incentive, apart from personal interest, for social scientists to specialize in their research on any of its component republics, including the Ukrainian SSR, and there was also no incentive to teach about them at universities. Hence there was a dearth of scholarly work on Soviet Ukraine from a social-scientific perspective. The exceptions, all but one of them émigrés—Jurij Borys, Bohdan Krawchenko, Bohdan R. Bociurkiw, Peter J. Potichnyj, Wsevolod Isajiw, and David Marples—were all the more notable. These authors, few as they were, laid the foundation for the study of post-1991 Ukraine, with major credit for disseminating their work going to the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies (CIUS) Press. Keywords: Canadian, social sciences, Soviet Ukraine, Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies. hen Omeljan Pritsak, in a paper he delivered at Carleton University in W January 1971, presented his tour d’horizon on the state of Ukrainian studies in the world, he barely mentioned Canada (139-52). Emphasizing the dearth of Ukrainian studies in Ukraine itself, his purpose was to draw attention to the inauguration of North America’s first Chair of Ukrainian Studies, at Harvard University. Two years later, of course, the Harvard Ukrainian Research Institute was formed, with Pritsak as inaugural director. -

Co-Operation Between the Viking Rus' and the Turkic Nomads of The

Csete Katona Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2018 CEU eTD Collection Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Reader CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 Co-operation between the Viking Rus’ and the Turkic nomads of the steppe in the ninth-eleventh centuries by Csete Katona (Hungary) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ External Supervisor CEU eTD Collection Budapest May 2018 I, the undersigned, Csete Katona, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies, declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. -

Презентаційний Каталог Presentation Catalogue І Нвестиці Йного Паспорту Вишг Ородськог О Району Vyshhorod District Investment Passport

ПРЕЗЕНТАЦІЙНИЙ КАТАЛОГ PRESENTATION CATALOGUE І НВЕСТИЦІ ЙНОГО ПАСПОРТУ ВИШГ ОРОДСЬКОГ О РАЙОНУ VYSHHOROD DISTRICT INVESTMENT PASSPORT КЛЮЧОВІ ФАКТИ KEY FACTS Вишгородський район Київської області має визначну історію та великий потенціал. Районний центр – місто Вишгород - вперше згадується ще у літописі «Повість временних літ» (946 рік), як резиденція княгині Ольги – Ольжин град, а відкриття Київської ГЕС з 1964 року створило унікальні можливості для розвитку території. Район розташований на обох берегах Київського моря та відзначається вдалим географічним розташуванням – межує з м. Київ – великим споживчим та бізнесовим центром країни. The Vyshhorod district of Kyiv oblast has a remarkable history and great potential. The district center Vyshhorod was first mentioned in The Tale of Bygone Years (946 year AD) as the residence of Princess Olga “Olzhyn Grad”. The opening of Kyiv Hydroelectric Power Plant created unique opportunities for the regional development since 1964. The district is located on both banks of the Kyiv Sea, and characterized by a good geographical location bordered with Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. Площа території Площа с/г угідь The area Area of agricultural land тисяч га тисяч га 203,1 thousand ha 46,0 thousand ha Водна поверхня Кількість населення Water surface Current population тисяч га тисяч чоловік 48,8 thousand ha 75,14 thousand people Населених пунктів Іноземні інвестиції Population centres Foreign investments 1 місто, 1 смт та 55 сіл млн дол. США 57 1 city, 1 town, 55 villages 72,9 mln usd Середня зарплата Зібрано податків Average salary Taxes collected грн млн грн 9987 uah 1148,5 mln uah Капітальні інвестиції Обсяг будівництва Capital investments Construction output млн грн млн грн 2179 mln uah 657,6 mln uah * Статистичні дані за 2018 рік. -

Changes for Children

Changes for Children June, 2006 Newsletter of the Project "Development of Integrated Social Services for Exposed Families and Children", financed by the European Union officially declared 2006 the Year of Child children homes, and to deliver assistance IN FOCUS Protection in Ukraine. One of the steps to families caring for orphans. The goals of toward providing child support is an 11 the Ukrainian State as outlined by the Children Rights fold increase in the financial grant to President are concurrent with the aims of the EU Project "Development of Integrated The international day of child protection has been celebrated on 1st June in Europe for Social Services for Exposed Families and more than 50 years. This date reminds adults, of the importance of children's rights: to Children" which, starting from 2005 is live and be brought up in a family, to freedom of thought, conscience and religion, to edu being implemented in Kyiv Oblast by the cation, rest and leisure as well as to protection from violence. Since 1991 when Ukraine Representative Office of 'EveryChild' in ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, the State has guaran Ukraine. The main goal of the Project is to teed to secure and protect children's rights. reduce the number of children living in res idential institutions and to support family > President Victor Yuschenko said this mother's on the birth of their children. He based care for children. Newly developed year "It is the sacred duty of our society, voiced a hope for a 2fold increase in Integrated Social Services have been the state and individuals to do everything financial support for mothers taking care established in 32 rayon and city adminis possible to ensure that Ukrainian children of children under the age of 3 years old, trations throughout Kyiv Oblast. -

Research Notes /Аналітичні Записки ЦПД Науоа/Аналитические Записки ЦПИ Науоа

Research Notes /Аналітичні записки ЦПД НаУОА/Аналитические записки ЦПИ НаУОА Research Note #4, 2019 Political Developments in Kyiv Oblast Prior 2019 Presidential Elections Ivan Gomza Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at the National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Senior Fellow at the School for Policy Analysis National University of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy Yuriy Matsiyevsky Series editor Center for Political Research Ostroh Academy National University Center for Political Research Ostroh Academy National University 2019 Research Notes /Аналітичні записки ЦПД НаУОА/Аналитические записки ЦПИ НаУОА At first glance Kyiv oblast, with its 1 754 949 inhabitants, barely impresses as a valuable prize in electoral campaign. After all, the oblast consists of 9 single-member districts that translate in 9 seats at the national parliament. When compared with 17 seats allocated to Dnipropetrovsk oblast, 13 – to Kharkiv, 12 to Donetsk, or Lviv oblast, and 11 to Odessa oblast, this does not look impressive. The power struggle in Kyiv oblast might seem of limited strategic importance. Such a conclusion is, however, erroneous as Kyiv oblast has several distinctive features, which makes it central in power competition and power distribution after each election. Firstly, the oblast is adjacent to the ultimate powerhouse of national politics, the city of Kyiv. The nine above-mentioned electoral districts comprise regional town areas which encircle the capital, set its administrative boundaries, contain its growth, limit the city’s capabilities to manage logistics and to provide infrastructural services. In fact, the lack of capacities forced the mayor of Kyiv to initiate the program to create a “Kyiv metropolitan area” which should bring closer housing, transportation, and administration across the city of Kyiv and the oblast emulating the Metropolis of Greater Paris. -

Documentary Evidence of Underground and Guerrilla Activities During the Nazi Occupation of Kiev and the Kiev Oblast'

Documentary Evidence of Underground and Guerrilla Activities During the Nazi Occupation of Kiev and the Kiev Oblast' Fond P-4 Opis’ 1 Underground CP(b)U obkom and materialon underground partisan activities around the Kiev oblast’ Fond P-4 Opis’ 2 Underground CP(b)U city committee on underground and partisan activities around the city Fond P-4 Opis’ 5 Documentary material of the party and Komsomol underground network and the partisan movement in Kiev and the Kiev oblast’ during the Nazi occupation /not approved by the party obkom 1 By Vladimir Danilenko, Director of the State Archive of the Kiev Oblast’ From the State Archive of the Kiev Oblast (GAKO) comes a collection of documents pertaining to underground and guerrilla activities during the German occupation of Kiev and the Kiev Oblast (Fond P-4). This collection was put together in the archives of the Kiev Oblast committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine CPU) in the late 1970s and early 1980s based on documents found in the stacks of the Kiev Oblast [party] committee, the oblast industrial committee, city and town committees of the CPU and и LKSMU (Communist League of Youth) of Kiev and Kiev oblsast’ and the party committee of MVD USSR. The collection was transferred to GAKO in 1991 together with the other fonds of the Kiev Oblast CPU Committee. Fond P-4 has six opisi systematized on the structural-chronological principle. This collection includes documents from the first, second and fifth opisi. There is not a single example in the history of warfare where a guerrilla movement and underground war effort played such a big role as it did during the last world war. -

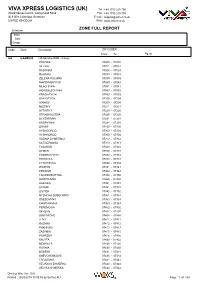

Viva Xpress Logistics (Uk)

VIVA XPRESS LOGISTICS (UK) Tel : +44 1753 210 700 World Xpress Centre, Galleymead Road Fax : +44 1753 210 709 SL3 0EN Colnbrook, Berkshire E-mail : [email protected] UNITED KINGDOM Web : www.vxlnet.co.uk Selection ZONE FULL REPORT Filter : Sort : Group : Code Zone Description ZIP CODES From To Agent UA UAAOD00 UA-Ukraine AOD - 4 days POLISKE 07000 - 07004 VILCHA 07011 - 07012 RADYNKA 07024 - 07024 RAHIVKA 07033 - 07033 ZELENA POLIANA 07035 - 07035 MAKSYMOVYCHI 07040 - 07040 MLACHIVKA 07041 - 07041 HORODESCHYNA 07053 - 07053 KRASIATYCHI 07053 - 07053 SLAVUTYCH 07100 - 07199 IVANKIV 07200 - 07204 MUSIIKY 07211 - 07211 DYTIATKY 07220 - 07220 STRAKHOLISSIA 07225 - 07225 OLYZARIVKA 07231 - 07231 KROPYVNIA 07234 - 07234 ORANE 07250 - 07250 VYSHGOROD 07300 - 07304 VYSHHOROD 07300 - 07304 RUDNIA DYMERSKA 07312 - 07312 KATIUZHANKA 07313 - 07313 TOLOKUN 07323 - 07323 DYMER 07330 - 07331 KOZAROVYCHI 07332 - 07332 HLIBOVKA 07333 - 07333 LYTVYNIVKA 07334 - 07334 ZHUKYN 07341 - 07341 PIRNOVE 07342 - 07342 TARASIVSCHYNA 07350 - 07350 HAVRYLIVKA 07350 - 07350 RAKIVKA 07351 - 07351 SYNIAK 07351 - 07351 LIUTIZH 07352 - 07352 NYZHCHA DUBECHNIA 07361 - 07361 OSESCHYNA 07363 - 07363 KHOTIANIVKA 07363 - 07363 PEREMOGA 07402 - 07402 SKYBYN 07407 - 07407 DIMYTROVE 07408 - 07408 LITKY 07411 - 07411 ROZHNY 07412 - 07412 PUKHIVKA 07413 - 07413 ZAZYMIA 07415 - 07415 POHREBY 07416 - 07416 KALYTA 07420 - 07422 MOKRETS 07425 - 07425 RUDNIA 07430 - 07430 BOBRYK 07431 - 07431 SHEVCHENKOVE 07434 - 07434 TARASIVKA 07441 - 07441 VELIKAYA DYMERKA 07442 - 07442 VELYKA