Neoliberal Metaphors in Presidential Discourse from Ronald Reagan to Donald Trump

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

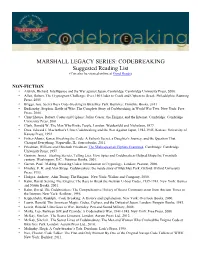

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

Consumerism in the 1920S: Collected Commentary

BECOMING MODERN: AMERICA IN THE 1920S PRIMARY SOURCE COLLECTION ONTEMPORAR Y HE WENTIES IN OMMENTARY T T C * Leonard Dove, The New Yorker, October 26, 1929 — CONSUMERISM — Mass-produced consumer goods like automobiles and ready-to-wear clothes were not new to the 1920s, nor were advertising or mail- order catalogues. But something was new about Americans’ relationship with manufactured products, and it was accelerating faster than it could be defined. Not only did the latest goods become necessities, consumption itself became a necessity, it seemed to observers. Was that good for America? Yes, said some—people can live in unprecedented comfort and material security. Not so fast, said others—can we predict where consumerism is taking us before we’re inextricably there? Something new has come to confront American democracy. Samuel Strauss The Fathers of the Nation did not foresee it. History had opened “Things Are in the Saddle” to their foresight most of the obstacles which might be expected The Atlantic Monthly to get in the way of the Republic—political corruption, extreme November 1924 wealth, foreign domination, faction, class rule; . That which has stolen across the path of American democracy and is already altering Americanism was not in their calculations. History gave them no hint of it. What is happening today is without precedent, at least so far as historical research has discovered. No reformer, no utopian, no physiocrat, no poet, no writer of fantastic romances saw in his dreams the particular development which is with us here and now. This is our proudest boast: “The American citizen has more comforts and conveniences than kings had two hundred years ago.” It is a fact, and this fact is the outward evidence of the new force which has crossed the path of American democracy. -

Prosperity Economics Building an Economy for All

ProsPerity economics Building an economy for All Jacob S. Hacker and Nate Loewentheil ProsPerity economics Building an economy for All Jacob S. Hacker and Nate Loewentheil Creative Commons (cc) 2012 by Jacob S. Hacker and Nate Loewentheil Notice of rights: This book has been published under a Creative Commons license (Attribution-NonCom- mercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported; to view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by-nc-sa/3.0/). This work may be copied, redistributed, or displayed by anyone, provided that proper at- tribution is given. ii / prosperity economics About the authors Jacob S. Hacker, Ph.D., is the Director of the Institution for Social and Policy Studies (ISPS), the Stanley B. Resor Professor of Political Science, and Senior Research Fellow in International and Area Studies at the MacMil- lan Center at Yale University. An expert on the politics of U.S. health and social policy, he is author of Winner-Take-All Politics: How Wash- ington Made the Rich Richer—And Turned Its Back on the Middle Class, with Paul Pierson (September 2010, paperback March 2011); The Great Risk Shift: The New Economic Insecurity and the Decline of the American Dream (2006, paperback 2008); The Divided Welfare State: The Battle Over Public and Private Social Benefits in the United States (2002); and The Road to Nowhere: The Genesis of President Clinton’s Plan for Health Security (1997), co-winner of the Brownlow Book Award of the National Academy of Public Administration. He is also co-author, with Paul Pierson, of Off Center: The Republican Revolution and the Erosion of American Democracy (2005), and has edited three volumes, most recently, Shared Responsibility, Shared Risk: Government, Markets and Social Policy in the Twenty-First Century, with Ann O'Leary (2012). -

9 Purple 18/2

THE CONCORD REVIEW 223 A VERY PURPLE-XING CODE Michael Cohen Groups cannot work together without communication between them. In wartime, it is critical that correspondence between the groups, or nations in the case of World War II, be concealed from the eyes of the enemy. This necessity leads nations to develop codes to hide their messages’ meanings from unwanted recipients. Among the many codes used in World War II, none has achieved a higher level of fame than Japan’s Purple code, or rather the code that Japan’s Purple machine produced. The breaking of this code helped the Allied forces to defeat their enemies in World War II in the Pacific by providing them with critical information. The code was more intricate than any other coding system invented before modern computers. Using codebreaking strategy from previous war codes, the U.S. was able to crack the Purple code. Unfortunately, the U.S. could not use its newfound knowl- edge to prevent the attack at Pearl Harbor. It took a Herculean feat of American intellect to break Purple. It was dramatically intro- duced to Congress in the Congressional hearing into the Pearl Harbor disaster.1 In the ensuing years, it was discovered that the deciphering of the Purple Code affected the course of the Pacific war in more ways than one. For instance, it turned out that before the Americans had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, Purple Michael Cohen is a Senior at the Commonwealth School in Boston, Massachusetts, where he wrote this paper for Tom Harsanyi’s United States History course in the 2006/2007 academic year. -

LGBTQ Guam and Hospitality of the Guamanian People

An LGBTQ Guide to Guam Håfa Adai, Welcome! As Lieutenant Governor of Guam and proud member of the LGBTQ community, I am grateful that Guam’s residents have given me the opportunity to help direct the island’s future. Also, Guam has just elected its first female Governor, and now holds the record for the largest women majority in U.S. history. Guam’s diverse political leadership is a direct reflection JOSHUA TENORIO, of the broadening views within our island community. THE HONORABLE LT. GOVERNOR I will advocate for policy that is fair and equal for all and will positively impact LGBTQ rights. I applaud the Guam Visitors Bureau’s efforts in developing the Guam travel industry to better serve LGBTQ travelers and give my full support to their ongoing efforts. We look forward to your visit and providing you with the adventure of a lifetime! Si Yu’os Ma’åse’ 23 Håfa Adai! (Greetings!) Contents The Guam Visitors Bureau (GVB) finds great joy in welcoming LGBTQ travelers to our beautiful island. 02 Welcome As you read this guide, we hope that it inspires you to visit our home and experience the warmth 04 LGBTQ Guam and hospitality of the Guamanian people. 06 LGBTQ Resources 16 Guam strongly supports the LGBTQ community, paving 08 Visiting Guam PILAR LAGUAÑA, the way for equality, celebrating diversity, and promoting With Other LGBTQ PRESIDENT & CEO, inclusivity. The Bureau is a proud member of the Destinations 12 Things to do International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association (IGLTA), GUAM VISITORS 09 Guam + Japan 12 Outdoors BUREAU where we continue our efforts to be a reliable resource for, and to better serve the needs of, all of our visitors. -

A Consumers' Republic: the Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar

A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Cohen, Lizabeth. 2004. A consumers’ republic: The politics of mass consumption in postwar America. Journal of Consumer Research 31(1): 236-239. Published Version doi:10.1086/383439 Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:4699747 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Reflections and Reviews A Consumers’ Republic: The Politics of Mass Consumption in Postwar America LIZABETH COHEN* istorians and social scientists analyzing the contem- sumer market. A wide range of economic interests and play- H porary world unfortunately have too little contact and ers all came to endorse the centrality of mass consumption hence miss some of the ways that their interests overlap and to a successful reconversion from war to peace. Factory the research of one field might benefit another. I am, there- assembly lines newly renovated with Uncle Sam’s dollars fore, extremely grateful that the Journal of Consumer Re- stood awaiting conversion from building tanks and muni- search has invited me to share with its readers an overview tions for battle to producing cars and appliances for sale to of my recent research on the political and social impact of consumers. the flourishing of mass consumption on twentieth-century If encouraging a mass consumer economy seemed to America. -

Economic Prosperity Element

ECONOMIC PROSPERITY LIVE GOALS, OBJECTIVES, AND POLICIES GOAL ECP 1 TALENT & HUMAN CAPITAL GOAL ECP 2 INCLUSIVE ENTREPRENEURSHIP WORK GOAL ECP 3 INDUSTRY CLUSTERS GOAL ECP 4 BUSINESS CLIMATE & COMPETITIVENESS GOAL ECP 5 EQUITY AND ECONOMIC INCLUSION PLAY GOAL ECP 6 ECONOMIC PLACEMAKING GOAL ECP 7 ECONOMIC LEADERSHIP & PARTNERSHIP GOAL ECP 8 COMMUNITY LIFE GROW Comprehensive Plan | 2019 ECONOMIC PROSPERITY ELEMENT WHAT IS THE ECONOMIC PROSPERITY ELEMENT? The Economic Prosperity Element is new to the City’s Comprehensive Plan and provides context for policy, resource allocation and guidance as to how the City will seek to promote prosperity as the Delray Beach’s economy develops and evolves. The International Economic Development Council defines economic development as “a process that influences growth and restructuring of an economy to enhance the economic well-being of a community.” Community benefits from a successful economic development approach and strategy including: 1) new business activity; 2) higher incomes; 3) wealth-building; and 4) tax revenues to fund public services and community life investments. Effective economic development involves a coordinated cross-disciplinary approach to business attraction, business development, business retention, workforce capacity-building, tourism, and infrastructure investments, as drivers of economic growth. The City has focused on growing local businesses, business retention and expansion, redevelopment and revitalization, downtown development, tourism and sports, arts and culture, special events, and community development as economic development strategies. While this approach has been effective, investments in people, place, and industry development are necessary to fill gaps in the city industries and economic outcomes. Additionally, Delray Beach’s prior economic success does not yet mean prosperity for all. -

Is Globalization a Source of Prosperity and Progress Or the Main Cause of Poverty? What Has to Be Done to Reduce Poverty?

Journal of Social Sciences, 1(1):13-17,2012 ISSN:2233-3878 Is Globalization a Source of Prosperity and Progress or the Main Cause of Poverty? What has to be done to Reduce Poverty? Valeri MODEBADZE* Abstract This article analyses globalization process and its positive and negative sides. Globalization is a double-edged phenomenon. This research is based on comparative method. Two contradictory approaches to understanding globalization are compared with each other. On the one hand, advocates of globalization argue that globalization is a positive phenomenon which promotes greater prosperity and increases living standards of people. On the other hand, opponents of globalization see it as the main cause of impoverishment and economic crisis. The problem of describing the effects of globalization is closely linked with these two contradictory approaches to understanding globalization. Keywords: globalization, positive and negative sides of globalization, transnational institutions, environmental degradation, global warming Introduction – Definition of Globalization national trade and international business operations. Thus, economic life has been progressively globalized. National Before we start comparing two contradictory ap- economies have been integrated into global economy and proaches to globalization, we have to define it. Globali- they have become so interdependent that they cannot func- zation refers to the growing interconnectedness of differ- tion separately from each other. One of the consequences of ent parts of the world. It is a process which gives rise to globalization is the emergence of multinational companies a complex form of interaction and interdependency. The and transnational corporations. These are very powerful world is becoming a global village and interdependence organizations that produce output in more than one state. -

Prosperity Without Growth?Transition the Prosperity to a Sustainable Economy 2009

Prosperity without growth? The transition to a sustainable economy to a sustainable The transition www.sd-commission.org.uk Prosperity England 2009 (Main office) 55 Whitehall London SW1A 2HH without 020 7270 8498 [email protected] Scotland growth? Osborne House 1 Osbourne Terrace, Haymarket Edinburgh EH12 5HG 0131 625 1880 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/scotland Wales Room 1, University of Wales, University Registry, King Edward VII Avenue, Cardiff, CF10 3NS Commission Development Sustainable 029 2037 6956 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/wales Northern Ireland Room E5 11, OFMDFM The transition to a Castle Buildings, Stormont Estate, Belfast BT4 3SR sustainable economy 028 9052 0196 [email protected] www.sd-commission.org.uk/northern_ireland Prosperity without growth? The transition to a sustainable economy Professor Tim Jackson Economics Commissioner Sustainable Development Commission Acknowledgements This report was written in my capacity as Economics Commissioner for the Sustainable Development Commission at the invitation of the Chair, Jonathon Porritt, who provided the initial inspiration, contributed extensively throughout the study and has been unreservedly supportive of my own work in this area for many years. For all these things, my profound thanks. The work has also inevitably drawn on my role as Director of the Research group on Lifestyles, Values and Environment (RESOLVE) at the University of Surrey, where I am lucky enough to work with a committed, enthusiastic and talented team of people carrying out research in areas relevant to this report. Their research is evident in the evidence base on which this report draws and I’m as grateful for their continuing intellectual support as I am for the financial support of the Economic and Social Research Council (Grant No: RES-152-25-1004) which keeps RESOLVE going. -

Certain Aspects of "Magic" in the Cryptological Background of the Various Official Investigations Into the Attack on P

REF ID:A485355 OF 'l'.BE V.AltIOUS OFFICIAL INVEmGATIONS mo 'l!BE A'.t'.J!ACK ON PEA.BL MRBOR ··. •· . ' I-.- REF ID:A485355 --;-~·;-:;-.:- ... -~.... , ""'-·I';"~-""",~-·;,'~;~~~-~~.\,-::):t~<.""',. -.~\~=---:~-.,,-1f~': ------== ,,.--.., "t-,-.\;' .,-~,-. Certain As;pects of 1tMsgie 11 in the Ct;r:ttol~eaJ.. De.ck.ground of the V{'J."':touc; Offic!.&.1. Invest1@(1ons into the Atttlck on Pearl Harbor INDEX Section l. Introduction • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 2. The Real Essence of the Problem • • • • • • • • • 11 A Ziev Look a.t the Revisionists Allegations of Conspiracy to Keep K:l.mmel and S'bort in the Da:rk • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • 18 4. Was MtlGIC Withheld from Kimmel and Short and, if so, ~ ••••••• ,, •••••••• • • 35 1 The tiWinds Code Message:B ' . ~ . .. 49 The Question of Sabota.g~f! • • • ti ~ • • • • • • • 53 Conclusions ....... ",., ....... 65 8. Epilogtte • • .. • • • • ' • ' It • Ill • • • • • • • • 60 11 11 APPENDIX 1: Pearl H&'bor in Pernpective1 by Dr. Louis Morton, Uni:ted States Na.val Institute Proceedi!!is,, Vo1. 81, No. 4, April 1955; P-.kl. 461'.:468 APPlitWIX 2: !lpea.rl Ra.rhor and the Revlsionists, 11 by Prof'. Robert H. Ferrc:Ll.. The Historian, Vol. XVII, No. 2, SprinS 19551 :Pl~· 215·233 REF ID:A485355 1. nmOD"OCTION More than 15 yea.rs have passed. since the Japanese, with unparalleled good luck, good luck that nov seem:s astoundinS, and vith a degree of skill unanticipated by the United, :3tates, executed their surprise attack on Pearl Harbor during the morning hours of 7 December 1941. It was an attack that constituted a. momentou::; disaster for the United States; it ma.de our Navy's Pacific Pleet, for all practica.l purposes, hors de combat for m.a.ny months. -

The Magic Flute

OCTOBER 09, 2015 THE FRIDAY | 8:00 PM OCTOBER 11, 2015 MAGIC SUNDAY | 4:00 PM OCTOBER 13, 2015 FLUTE TUESDAY | 7:00 PM FLÂNEUR FOREVER Honolulu Ala Moana Center (808) 947-3789 Royal Hawaiian Center (808) 922-5780 Hermes.com AND WELCOME TO AN EXCITING NEW SEASON OF OPERAS FROM HAWAII OPERA THEATRE. We are thrilled to be opening our 2014) conducts, and Allison Grant As always we are grateful to you, season with one of Mozart’s best- (The Merry Widow, 2004) directs this our audience, for attending our loved operas: The Magic Flute. This new translation of The Magic Flute by performances and for the support colorful production comes to us Jeremy Sams. you give us in so many ways from Arizona Opera, where it was throughout the year. Without your created by Metropolitan Opera This will be another unforgettable help we simply could not continue stage director, Daniel Rigazzi. season for HOT with three to bring the world’s best opera to Inspired by the work of the French sensational operas, including Hawaii each year. surrealist painter, René Magritte, a stunning new production of the production is fi lled with portals– Benjamin Britten’s A Midsummer But now sit back and enjoy Mozart’s doorways and picture frames–that Night’s Dream, directed by Henry The Magic Flute. lead the viewer from reality to Akina, with videography by Adam dreams. With a cast that includes Larsen (Siren Song, 2015) and a MAHALO Antonio Figueroa as Tamino and So spectacular production of Verdi’s Il Young Park as the formidable Queen Trovatore designed by Peter Dean Henry G. -

Local Interpretations of Degrowth—Actors, Arenas and Attempts to Influence Policy

sustainability Article Local Interpretations of Degrowth—Actors, Arenas and Attempts to Influence Policy Katarina Buhr 1, Karolina Isaksson 2,3,* ID and Pernilla Hagbert 3 1 IVL Swedish Environmental Research Institute, Climate and Sustainable Cities Unit, 10031 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] 2 VTI, the Swedish National Road and Transport Research Institute, Division of Mobility, Actors and Planning Processes, 10215 Stockholm, Sweden 3 KTH Royal Institute of Technology, Department of Urban Planning and Environment, 10044 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +46-766-334-328 Received: 3 May 2018; Accepted: 4 June 2018; Published: 6 June 2018 Abstract: During the last decade, degrowth has developed into a central research theme within sustainability science. A significant proportion of previous works on degrowth has focused on macro-level units of analysis, such as global or national economies. Less is known about local interpretations of degrowth. This study explored interpretations of growth and degrowth in a local setting and attempts to integrate degrowth ideas into local policy. The work was carried out as a qualitative single-case study of the small town of Alingsås, Sweden. The results revealed two different, yet interrelated, local growth discourses in Alingsås: one relating to population growth and one relating to economic growth. Individuals participating in the degrowth discourse tend to have a sustainability-related profession and/or background in civil society. Arenas for local degrowth discussions are few and temporary and, despite some signs of influence, degrowth-related ideas have not had any significant overall impact on local policy and planning.