Teaching the Conflicts Neal Stephenson's Cryptonomicon And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

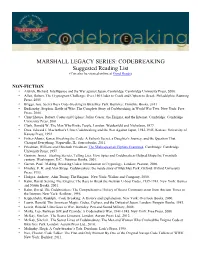

CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can Also Be Viewed Online at Good Reads)

MARSHALL LEGACY SERIES: CODEBREAKING Suggested Reading List (Can also be viewed online at Good Reads) NON-FICTION • Aldrich, Richard. Intelligence and the War against Japan. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000. • Allen, Robert. The Cryptogram Challenge: Over 150 Codes to Crack and Ciphers to Break. Philadelphia: Running Press, 2005 • Briggs, Asa. Secret Days Code-breaking in Bletchley Park. Barnsley: Frontline Books, 2011 • Budiansky, Stephen. Battle of Wits: The Complete Story of Codebreaking in World War Two. New York: Free Press, 2000. • Churchhouse, Robert. Codes and Ciphers: Julius Caesar, the Enigma, and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001. • Clark, Ronald W. The Man Who Broke Purple. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1977. • Drea, Edward J. MacArthur's Ultra: Codebreaking and the War Against Japan, 1942-1945. Kansas: University of Kansas Press, 1992. • Fisher-Alaniz, Karen. Breaking the Code: A Father's Secret, a Daughter's Journey, and the Question That Changed Everything. Naperville, IL: Sourcebooks, 2011. • Friedman, William and Elizebeth Friedman. The Shakespearian Ciphers Examined. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1957. • Gannon, James. Stealing Secrets, Telling Lies: How Spies and Codebreakers Helped Shape the Twentieth century. Washington, D.C.: Potomac Books, 2001. • Garrett, Paul. Making, Breaking Codes: Introduction to Cryptology. London: Pearson, 2000. • Hinsley, F. H. and Alan Stripp. Codebreakers: the inside story of Bletchley Park. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993. • Hodges, Andrew. Alan Turing: The Enigma. New York: Walker and Company, 2000. • Kahn, David. Seizing The Enigma: The Race to Break the German U-boat Codes, 1939-1943. New York: Barnes and Noble Books, 2001. • Kahn, David. The Codebreakers: The Comprehensive History of Secret Communication from Ancient Times to the Internet. -

Hackers Wanted : an Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market / Martin C

CHILDREN AND FAMILIES The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit institution that EDUCATION AND THE ARTS helps improve policy and decisionmaking through ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT research and analysis. HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE This electronic document was made available from INFRASTRUCTURE AND www.rand.org as a public service of the RAND TRANSPORTATION Corporation. INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS LAW AND BUSINESS NATIONAL SECURITY Skip all front matter: Jump to Page 16 POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY Support RAND Purchase this document TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY Browse Reports & Bookstore Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore the RAND National Security Research Division View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non-commercial use only. Unauthorized posting of RAND electronic documents to a non-RAND website is prohibited. RAND electronic documents are protected under copyright law. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please see RAND Permissions. This report is part of the RAND Corporation research report series. RAND reports present research findings and objective analysis that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND reports undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for re- search quality and objectivity. H4CKER5 WANTED An Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market MARTIN C. LIBICKI DAVID SENTY C O R P O R A T I O N JULIA POLLAK NATIONAL SECURITY RESEARCH DIVISION H4CKER5 WANTED An Examination of the Cybersecurity Labor Market MARTIN C. -

The Brain in a Vat in Cyberpunk: the Persistence of the Flesh

Stud. Hist. Phil. Biol. & Biomed. Sci. 35 (2004) 287–305 www.elsevier.com/locate/shpsc The brain in a vat in cyberpunk: the persistence of the flesh Dani Cavallaro 1 Waterside Place, London NW1 8JT, UK Abstract This essay argues that the image of the brain in a vat metaphorically encapsulates articu- lations of the relationship between the corporeal and the technological dimensions found in cyberpunk fiction and cinema. Cyberpunk is concurrently concerned with actual and imaginary metamorphoses of biological organisms into machines, and of mechanical appara- tuses into living entities. Its recurring representation of human beings hooked up to digital matrices vividly recalls the envatted brain activated by electric stimuli, which Hilary Putnam has theorized in the context of contemporary epistemology. At the same time, cyberpunk imaginatively raises the same epistemological questions instigated by Putnam. These concern the cognitive processes associated with the collusion of human and mechanical creatures, and related metaphysical and ethical issues spawned by such processes. As a philosophical trope, the brain in a vat would appear to pivot on the notion of a disembodied subject consisting of sheer mentation. However, literary and cinematic interpretations of the image in cyberpunk persistently foreground the obdurate materiality of the flesh—often in its most grisly and grotesque incarnations. # 2004 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Brains in vats; Materiality; Disembodiment; Cyborgs; Cyberpunk What is here proposed is that the brain in a vat image, an important trope in contemporary epistemology, is also an intriguing metaphor for one of cyberpunk’s pivotal preoccupations: namely, the relationship between the body and technology. -

Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of the Worlds by Steven Levy 08.18.08

Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of t... http://www.wired.com/print/culture/art/magazine/16-09/mf_ste... << Back to Article WIRED MAGAZINE: 16.09 Novelist Neal Stephenson Once Again Proves He's the King of the Worlds By Steven Levy 08.18.08 Illustration: Nate Van Dyke Tonight's subject at the History Book Club: the Vikings. This is primo stuff for the men who gather once a month in Seattle to gab about some long-gone era or icon, from early Romans to Frederick the Great. You really can't beat tales of merciless Scandinavian pirate forays and bloody ninth-century clashes. To complement the evening's topic, one clubber is bringing mead. The dinner, of course, is meat cooked over fire. "Damp will be the weather, yet hot the pyre in my backyard," read the email invite, written by host Njall Mildew-Beard. That's Neal Stephenson, best-selling novelist, cult science fictionist, and literary channeler of the hacker mindset. For Stephenson, whose books mash up past, present, and future—and whose hotly awaited new work imagines an entire planet, with 7,000 years of its own history—the HBC is a way to mix background reading and socializing. "Neal was already doing the research," says computer graphics pioneer Alvy Ray Smith, who used to host the club until he moved from a house to a less convenient downtown apartment. "So why not read the books and talk about them, too?" With his shaved head and (mildewless) beard, Stephenson could cut something of an imposing figure. -

Odalisque (Baroque Cycle) Online

ciBr0 (Download free pdf) Odalisque (Baroque Cycle) Online [ciBr0.ebook] Odalisque (Baroque Cycle) Pdf Free Neal Stephenson ebooks | Download PDF | *ePub | DOC | audiobook Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #3361818 in Books 2015-06-09Formats: Audiobook, MP3 Audio, UnabridgedOriginal language:EnglishPDF # 1 6.75 x .50 x 5.25l, Running time: 13 HoursBinding: MP3 CD | File size: 15.Mb Neal Stephenson : Odalisque (Baroque Cycle) before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Odalisque (Baroque Cycle): 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Book Three of the Author's Baroque CycleBy Steven M. AnthonyOdalisque is Book Three of Volume I (Quicksilver) of the author’s Baroque Cycle. Book One introduced Daniel Waterhouse, a 17th century member of the English Royal Society. Both the college years and twilight years of Waterhouse’s life are covered in separate threads. Book Two follows the exploits of Half-Cocked Jack Shaftoe and his traveling companion Eliza, whom he liberated from the Turks at the Siege of Vienna.Book Three merges the characters of Books One and Two during the historical period covering the reigns of Charles II, James II, Louis XIV and William of Orange. This equates to the middle age of Daniel Waterhouse, a Puritan who is navigating the perilous religious landscape between the Protestant King Charles II and the Catholic King James II. Meanwhile Eliza shuttles between the Versailles court of Louis XIV and the Dutch Republic, acting as both financial manipulator and covert operative. Various other historical figures make their appearances throughout the pages.If you enjoyed Books One and Two, then this is more of the same. -

9 Purple 18/2

THE CONCORD REVIEW 223 A VERY PURPLE-XING CODE Michael Cohen Groups cannot work together without communication between them. In wartime, it is critical that correspondence between the groups, or nations in the case of World War II, be concealed from the eyes of the enemy. This necessity leads nations to develop codes to hide their messages’ meanings from unwanted recipients. Among the many codes used in World War II, none has achieved a higher level of fame than Japan’s Purple code, or rather the code that Japan’s Purple machine produced. The breaking of this code helped the Allied forces to defeat their enemies in World War II in the Pacific by providing them with critical information. The code was more intricate than any other coding system invented before modern computers. Using codebreaking strategy from previous war codes, the U.S. was able to crack the Purple code. Unfortunately, the U.S. could not use its newfound knowl- edge to prevent the attack at Pearl Harbor. It took a Herculean feat of American intellect to break Purple. It was dramatically intro- duced to Congress in the Congressional hearing into the Pearl Harbor disaster.1 In the ensuing years, it was discovered that the deciphering of the Purple Code affected the course of the Pacific war in more ways than one. For instance, it turned out that before the Americans had dropped nuclear bombs on Japan, Purple Michael Cohen is a Senior at the Commonwealth School in Boston, Massachusetts, where he wrote this paper for Tom Harsanyi’s United States History course in the 2006/2007 academic year. -

LGBTQ Guam and Hospitality of the Guamanian People

An LGBTQ Guide to Guam Håfa Adai, Welcome! As Lieutenant Governor of Guam and proud member of the LGBTQ community, I am grateful that Guam’s residents have given me the opportunity to help direct the island’s future. Also, Guam has just elected its first female Governor, and now holds the record for the largest women majority in U.S. history. Guam’s diverse political leadership is a direct reflection JOSHUA TENORIO, of the broadening views within our island community. THE HONORABLE LT. GOVERNOR I will advocate for policy that is fair and equal for all and will positively impact LGBTQ rights. I applaud the Guam Visitors Bureau’s efforts in developing the Guam travel industry to better serve LGBTQ travelers and give my full support to their ongoing efforts. We look forward to your visit and providing you with the adventure of a lifetime! Si Yu’os Ma’åse’ 23 Håfa Adai! (Greetings!) Contents The Guam Visitors Bureau (GVB) finds great joy in welcoming LGBTQ travelers to our beautiful island. 02 Welcome As you read this guide, we hope that it inspires you to visit our home and experience the warmth 04 LGBTQ Guam and hospitality of the Guamanian people. 06 LGBTQ Resources 16 Guam strongly supports the LGBTQ community, paving 08 Visiting Guam PILAR LAGUAÑA, the way for equality, celebrating diversity, and promoting With Other LGBTQ PRESIDENT & CEO, inclusivity. The Bureau is a proud member of the Destinations 12 Things to do International Gay and Lesbian Travel Association (IGLTA), GUAM VISITORS 09 Guam + Japan 12 Outdoors BUREAU where we continue our efforts to be a reliable resource for, and to better serve the needs of, all of our visitors. -

Top Left-Hand Corner

The four novels Hyperion, The Fall of Hyperion, Endymion and The Rise of Endymion constitute the Hyperion Cantos by the American science fiction writer Dan Simmons. This galactic-empire, epic, science fiction narrative contains a plethora of literary references. The dominant part comes from the nineteenth-century Romantic poet John Keats. The inclusion of passages from his poetry and letters is pursued in my analysis. Employing Lubomír Doležel’s categorizations of intertextuality— “transposition,” “expansion,” and “displacement”—I seek to show how Keats’s writings and his persona constitute a privileged intertext in Simmons’s tetralogy and I show its function. Simmons constructs subsidiary plots, some of which are driven by Keats’s most well-known poetry. In consequence, some of the subplots can be regarded as rewrites of Keats’s works. Although quotations of poetry have a tendency to direct the reader’s attention away from the main plot, slowing down the narrative, such passages in the narratives evoke Keats’s philosophy of empathy, beauty and love, which is fundamental for his humanism. For Keats, the poet is a humanist, giving solace to mankind through his poetry. I argue that the complex intertextual relationships with regards to Keats’s poetry and biography show the way Simmons expresses humanism as a belief in man’s dignity and worth, and uses it as the basis for his epic narrative. Keywords: Dan Simmons; The Hyperion Cantos; John Keats’s poetry and letters; intertextuality; empathy; beauty; love; humanism. Gräslund 2 The American author Dan Simmons is a prolific writer who has published in different genres. -

Emergence, AI and Intellectual Property

The Emergent1 Property2 Market3 Jon Crowcroft, University of Cambridge, Computer Laboratory Abstract The title of this piece is a somewhat heavy-handed word play. The property market I’m writing about is the market in Intellectual Property, which is broken in so many ways, evidenced by the existence of patent mountains and patent trolls, fighting over how many angles they can fit in the 360 degrees around the head of a pin, rather than actually innovating. (It is well known in creative tech circles that pausing to talk to the IP lawyers would never have led to the discovery of the Internet Protocol). The Emergent Property I’m referring to is the possibility that such a complex system could fairly suddenly exhibit some new behavior. In this article, I speculate that this new behavior could just be that the idea of property ceases to exist. The article is written somewhat derivatively after the 1960s SF style of writers such as Cyril Kornbluth, JG Ballard, and John Brunner. Any resemblance to their very creative output is entirely good luck rather than actual skill. 1 A good example of emergence is described in Stephenson’s Anathem book. Complex systems suddenly exhibit simple, powerful effects, fireflies flashing and synchronizing all together in phase, or a murmuration of starlings being common natural examples. Crystalisation. See also footnote 33. 2 Some people have proposed putting the UK’s Land Registry (the national record of property) on the blockchain. Blockchains, or distributed ledgers, are suitable for storing information you wish to remain immutable, in a decentralized way where you cannot find any single trustworthy third party. -

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D

The Hugo Awards for Best Novel Jon D. Swartz Game Design 2013 Officers George Phillies PRESIDENT David Speakman Kaymar Award Ruth Davidson DIRECTORATE Denny Davis Sarah E Harder Ruth Davidson N3F Bookworms Holly Wilson Heath Row Jon D. Swartz N’APA George Phillies Jean Lamb TREASURER William Center HISTORIAN Jon D Swartz SECRETARY Ruth Davidson (acting) Neffy Awards David Speakman ACTIVITY BUREAUS Artists Bureau Round Robins Sarah Harder Patricia King Birthday Cards Short Story Contest R-Laurraine Tutihasi Jefferson Swycaffer Con Coordinator Welcommittee Heath Row Heath Row David Speakman Initial distribution free to members of BayCon 31 and the National Fantasy Fan Federation. Text © 2012 by Jon D. Swartz; cover art © 2012 by Sarah Lynn Griffith; publication designed and edited by David Speakman. A somewhat different version of this appeared in the fanzine, Ultraverse, also by Jon D. Swartz. This non-commercial Fandbook is published through volunteer effort of the National Fantasy Fan Federation’s Editoral Cabal’s Special Publication committee. The National Fantasy Fan Federation First Edition: July 2013 Page 2 Fandbook No. 6: The Hugo Awards for Best Novel by Jon D. Swartz The Hugo Awards originally were called the Science Fiction Achievement Awards and first were given out at Philcon II, the World Science Fiction Con- vention of 1953, held in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The second oldest--and most prestigious--awards in the field, they quickly were nicknamed the Hugos (officially since 1958), in honor of Hugo Gernsback (1884 -1967), founder of Amazing Stories, the first professional magazine devoted entirely to science fiction. No awards were given in 1954 at the World Science Fiction Con in San Francisco, but they were restored in 1955 at the Clevention (in Cleveland) and included six categories: novel, novelette, short story, magazine, artist, and fan magazine. -

Neal Stephenson Rides Again Heaven Is in the Cloud in the Prolific Science-Fiction Writer’S New Tome

BOOKS & ARTS COMMENT Digital lives could allow us to construct our own reality. FICTION A digital god: Neal Stephenson rides again Heaven is in the Cloud in the prolific science-fiction writer’s new tome. Paul McEuen watches in wonder. eal Stephenson likes to blow things Fall starts with awry, and he dies. Almost. His body is up. In Seveneves (2015), for instance, Dodge preparing for medically kept alive, because his will stipu- the prolific science-fiction writer an unnamed routine lates that his brain be preserved until technol- Ndetonated the Moon, then played out how medical procedure. ogy is capable of regenerating it. This might humanity tried to save itself from extinc- As the morning not lead anywhere beyond a disembodied NEAL/GETTY LEON tion. In his new tome, Fall, the metaphori- unspools, he notices head on ice, joining the likes of psychologist cal explosion kills just one man. But this is a pair of books on James Bedford — were it not for the billions an individual sitting on a few billion dollars, Greek and Norse in Dodge’s bank account, managed by his and longing to escape the shackles of mortal- myths left behind executor and former employee Corvallis ity. The aftermath of the blast is thus just as by his grandniece, Fall; or, Dodge in Kawasaki. (Corvallis, from the Latin for powerful, and changes the fate of humanity Sophia. At his favour- Hell crow, denotes intelligence and inscrutability. just as profoundly. ite bakery, the owner NEAL STEPHENSON Names map characters in Fall; Stephenson The book’s billionaire protagonist is presents him with a William Morrow has a lot of balls in the air, so he gives you Richard ‘Dodge’ Forthrast, a tech-head in near-perfect apple. -

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics

Science Fiction Stories with Good Astronomy & Physics: A Topical Index Compiled by Andrew Fraknoi (U. of San Francisco, Fromm Institute) Version 7 (2019) © copyright 2019 by Andrew Fraknoi. All rights reserved. Permission to use for any non-profit educational purpose, such as distribution in a classroom, is hereby granted. For any other use, please contact the author. (e-mail: fraknoi {at} fhda {dot} edu) This is a selective list of some short stories and novels that use reasonably accurate science and can be used for teaching or reinforcing astronomy or physics concepts. The titles of short stories are given in quotation marks; only short stories that have been published in book form or are available free on the Web are included. While one book source is given for each short story, note that some of the stories can be found in other collections as well. (See the Internet Speculative Fiction Database, cited at the end, for an easy way to find all the places a particular story has been published.) The author welcomes suggestions for additions to this list, especially if your favorite story with good science is left out. Gregory Benford Octavia Butler Geoff Landis J. Craig Wheeler TOPICS COVERED: Anti-matter Light & Radiation Solar System Archaeoastronomy Mars Space Flight Asteroids Mercury Space Travel Astronomers Meteorites Star Clusters Black Holes Moon Stars Comets Neptune Sun Cosmology Neutrinos Supernovae Dark Matter Neutron Stars Telescopes Exoplanets Physics, Particle Thermodynamics Galaxies Pluto Time Galaxy, The Quantum Mechanics Uranus Gravitational Lenses Quasars Venus Impacts Relativity, Special Interstellar Matter Saturn (and its Moons) Story Collections Jupiter (and its Moons) Science (in general) Life Elsewhere SETI Useful Websites 1 Anti-matter Davies, Paul Fireball.