Historical Cryptography 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Polish Mathematicians Finding Patterns in Enigma Messages

Fall 2006 Chris Christensen MAT/CSC 483 Machine Ciphers Polyalphabetic ciphers are good ways to destroy the usefulness of frequency analysis. Implementation can be a problem, however. The key to a polyalphabetic cipher specifies the order of the ciphers that will be used during encryption. Ideally there would be as many ciphers as there are letters in the plaintext message and the ordering of the ciphers would be random – an one-time pad. More commonly, some rotation among a small number of ciphers is prescribed. But, rotating among a small number of ciphers leads to a period, which a cryptanalyst can exploit. Rotating among a “large” number of ciphers might work, but that is hard to do by hand – there is a high probability of encryption errors. Maybe, a machine. During World War II, all the Allied and Axis countries used machine ciphers. The United States had SIGABA, Britain had TypeX, Japan had “Purple,” and Germany (and Italy) had Enigma. SIGABA http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/SIGABA 1 A TypeX machine at Bletchley Park. 2 From the 1920s until the 1970s, cryptology was dominated by machine ciphers. What the machine ciphers typically did was provide a mechanical way to rotate among a large number of ciphers. The rotation was not random, but the large number of ciphers that were available could prevent depth from occurring within messages and (if the machines were used properly) among messages. We will examine Enigma, which was broken by Polish mathematicians in the 1930s and by the British during World War II. The Japanese Purple machine, which was used to transmit diplomatic messages, was broken by William Friedman’s cryptanalysts. -

CHAPTER 8 a History of Communications Security in New Zealand

CHAPTER 8 A History of Communications Security in New Zealand By Eric Morgon Early Days “Admiralty to Britannia Wellington. Comence hostilities at once with Germany in accordance with War Standing Orders.” This is an entry in the cipher log of HMS Philomel dated 5 August, 1914. HMS Philomel was a cruiser of the Royal Navy and took part in the naval operations in the Dardanelles during the ill-fated Gallipoli campaign. Philomel’s cipher logs covering the period 1914 to 1918 make interesting reading and show how codes and ciphers were used extensively by the Royal Navy during World War 1. New Zealand officers and ratings served on board Philomel and thus it can be claimed that the use of codes and ciphers by Philomel are part of the early history of communications security in New Zealand. Immediately following the codes to Navy Office, the Senior Naval Officer New Zealand was advised that Cypher G and Cypher M had been compromised and that telegrams received by landline in these ciphers were to be recoded in Code C before transmission by Wireless Telegraphy (W/T) Apparently Cypher G was also used for cables between the Commonwealth Navy Board in Melbourne and he British Consul in Noumea. The Rear Admiral Commanding Her Majesty’s Australian Fleet instructed that when signalling by WT every odd numbered code group was to be a dummy. It is interesting to note that up until the outbreak of hostilities no provision had been made for the storage of code books or for precautions to prevent them from falling into enemy hands. -

History and Modern Cryptanalysis of Enigma's Pluggable Reflector

History and Modern Cryptanalysis of Enigma’s Pluggable Reflector Olaf Ostwald and Frode Weierud ABSTRACT: The development history of Umkehrwalze Dora (UKWD), Enigma's pluggable reflector, is presented from the first ideas in the mid-1920s to the last development plans and its actual usage in 1945. An Enigma message in three parts, enciphered with UKWD and intercepted by the British on 11 March 1945, is shown. The successful recovery of the key of this message is described. Modern computer-based cryptanalysis is used to recover the wiring of the unknown “Uncle Dick,” which the British called this field-rewirable reflector. The attack is based on the known ciphertext and plaintext pair from the first part of the intercept. After recovery of the unknown reflector wiring and the daily key the plaintext of the second part of the message is revealed. KEYWORDS: Enigma, cryptanalysis, Uncle Dick, Umkehrwalze Dora, UKWD, unsolved ciphers Address correspondence to Frode Weierud, Bjerkealleen 17, 1385 Asker, Norway. Email: [email protected] 1. Introduction Uncle Dick,1 as it was called by the codebreakers of Bletchley Park (BP), or Umkehrwalze Dora (UKWD), as designated by the Germans, was the nickname of a special pluggable reflector,2 used as the leftmost wheel within the scrambler 3 of the Enigma. The electro-mechanical cipher machine Enigma (from Greek αίνιγµα for “riddle”) was the backbone of the German Wehrmacht during World War II. Arthur Scherbius, a German promoted electrical engineer and inventor of considerable standing, invented Enigma in 1918 [14]. Subsequently it was improved and then used by all three parts of the German armed forces, namely army (Heer), air force (Luftwaffe), and military navy (Kriegsmarine), for enciphering and deciphering of their secret messages. -

National Security Agency (NSA) Document: a History of U.S

Description of document: National Security Agency (NSA) document: A History of U.S. Communications Security Post World-War II – released under Mandatory Declassification Review (MDR) Released date: February 2011 Posted date: 07-November-2011 Source of document: National Security Agency Declassification Services (DJ5) Suite 6884, Bldg. SAB2 9800 Savage Road Ft. George G. Meade, MD, 20755-6884 Note: Although the titles are similar, this document should not be confused with the David G. Boak Lectures available: http://www.governmentattic.org/2docs/Hist_US_COMSEC_Boak_NSA_1973.pdf The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -----------------------------------------------------------------------~~) '; I .:· ! _k:::._,.l COMitfll A HISTORY OF U.S. -

A Review Analysis of Two Fish Algorithm Cryptography Quantum Computing

IJCSN International Journal of Computer Science and Network, Volume 6, Issue 1, February 2017 ISSN (Online) : 2277-5420 www.IJCSN.org Impact Factor: 1.5 A Review Analysis of Two Fish Algorithm Cryptography Quantum Computing 1 Sukhvandna Abhi, 2 Umesh Sehgal 1, 2 GNA University Phagwara Abstract - In this analysis paper we tend to describe the evolution of cryptography ranging from the start of the twentieth century and continued into this day. Last 10 years quantum computing can begin to trounce everyday computers, resulting in breakthroughs in computer science. Specifically within the cryptography used from 1900 till the tip of war II.Quantum technologies supply immoderate secure communication sensors of unprecedented exactness and computers that square measure exponentially a lot of powerful than any mainframe for a given task. We compare the performance of the 5 AES finalists one kind of common software package platforms current 32-bit CPUs and high finish sixty four bit CPUs. Our intent is to indicate roughly however the algorithm’s speeds compare across a range of CPUs.The future of cryptography primarily based within the field of natural philosophy and by analyzing the hope to supply a allot of complete image of headed the 2 mail algorithms utilized in cryptography world. Keywords - Cryptography ancient secret writing system 1. Introduction regulated wherever the primary letter is substituted by the last letter, the second letter by the second to last letter then ryptography may be a subject that has been studied on. as a result of it's a monoalphabetic cipher and may and applied since ancient Roman times, and have only 1 doable key, this cipher is comparatively weak; Canalysis into higher coding ways continues to the but this wasn't a viable concern throughout its time as current day. -

TICOM: the Last Great Secret of World War II Randy Rezabek Version of Record First Published: 27 Jul 2012

This article was downloaded by: [Randy Rezabek] On: 28 July 2012, At: 18:04 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Intelligence and National Security Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/fint20 TICOM: The Last Great Secret of World War II Randy Rezabek Version of record first published: 27 Jul 2012 To cite this article: Randy Rezabek (2012): TICOM: The Last Great Secret of World War II, Intelligence and National Security, 27:4, 513-530 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2012.688305 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and- conditions This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. Intelligence and National Security Vol. 27, No. 4, 513–530, August 2012 TICOM: The Last Great Secret of World War II RANDY REZABEK* ABSTRACT Recent releases from the National Security Agency reveal details of TICOM, the mysterious 1945 operation targeting Germany’s cryptologic secrets. -

Docid: 383869,.9

.. DOCID: 383869,.9 / ,1/111 [ Der Fall WICHER:GermanKnowledge of i Polish Success on ENIGMA BY JOSEPH A. MEYER T'op Bed pi blat'" a In 19.39 the Germans found evidf'nce. including decrypts, that a Polish cryptanalytic organization, WICHER: had been readin!! the ENIGMA. Documents and interrogations did not reveal how the ma chine could have been read, and after some changes in the indicator system and plug/fings, the matter was dropped. In 1943, further evidence of prewar Polish success, and the Mrong appearance that Navy ENIGMA was being read by the British and US., caused a crypto security crisis. A spy in the U.S. NavyDepartment reported the reading of V-boat keys. ENIGMA security was studied. and many changes in the machine and its uWf.:e were undertaken. By 1944 the Germans acted and spoke as if they knew ENIGMA traffic was being read by the Allies, but they suspected betrayal or compromise of keys. Medium grade ciphers were also improved, and radiQ security was much im proVf'd. Users were forbidden to send secret or top .~ecrf!t information or operational orders over ENIGMA. Through all of this. German con /idence in the TUNNY cipher teleprinter (which wa.~ al.~o being read) neller wavered. The key to German suspicions of ENIGMA appears to have been the knowledge of Polish prewar successes; after which the wartime ENIGMA exploitation hunk by a thread for five and one-half ~~. I I. DER FALL WICHER' 1n late 19:39. after their rapid conquest of Poland. the German OKH (Oberkommando des Heeres, Army High Command) and OKW (Oherkommando der Wehrmacht, Armed Forces High Command) cryptanalysts obtained definite proof, incllldin~ decrypts of German messag-cs. -

UK/US COMSEC Conference Forwarded Herewith Is a Copy of a UK Paper Reviewing the Present Statue of UK Cryptographic Equipments

REF ID:A522534 Classification 14 Sept 53 FRCih NSA-41, Mr. Austin TO: Mr. Friedman Received 1 cop,y or the item listed below: Memo for Members of the U.S. Delegation, dtd 11 Sept 53 Copy No. 16 of TOP S.ECRET CONTROL NO. 5.3-41-183 Classification Declassified and approved for release by NSA on 06-25-2014 pursuantto E.O. 1352e ..•.. ·---·----·---·-· -·-· ........... ___ ....._______________ .. __ .. --- .. -· ........ ........ ________ ............... -... .............. .... ------ REF ID:A522534 'T10P SECRET 11 September 1953 MEMORANDUM FOR MEMBERS OF THE U.. S. DELEGATION SUBJECT: UK/US COMSEC Conference Forwarded herewith is a copy of a UK paper reviewing the present statue of UK cryptographic equipments.. This is an advance version which has not received final approval and ia subject to amendment both before and during the Conference. ~(21~FRANK C. AUSTIN iOP SEefU:T ec [q-I~Ot 11UrHR · ~ . ·I i COPY / t .OF ·: ~~:rlt,::i r'AGE Uf· t ·· PAuE:S TOP SECRET 'feP SEism!iT · SB6URl'fY Ilfti'OfiMit:'flOJi JI.K. CRYPTOGRAPHIC §QUIPMENTS PART I. LITERAL CYPHER MACHINESo 1. Machine Requiring no §xterr;1~l Source of Power. (a) PORTEX. A sme.ll hand operated ott-line tape printing cypher machine with an electrical permuting maze designed tor low echelon wse. Electrical power to operate the maze is derived tram a self-contained 45-volt dry battery good tor over 100,000 operations. The ct-yptographic unit consists ot an eight 26-point rotor maze with a crossover at the cypher end; the rotors step in two foul""rotor cyclom.etr1c cascades. Each rotor consists ot an insert and a housing; the insert is selected from a set of sixteen and can be fitted in the housing in any one or the twenty=six possible angular positions, the housing is fitted with a rotatable alphabet tyre. -

British Diplomatic Cipher Machines in the Early Cold War, 1945-1970

King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1080/02684527.2018.1543749 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Easter, D. (2018). Protecting Secrets: British diplomatic cipher machines in the early Cold War, 1945-1970. Intelligence and National Security, 34(2), 157-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/02684527.2018.1543749 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

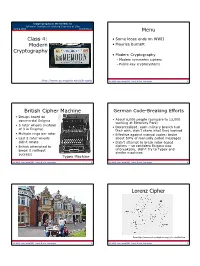

Lorenz Cipher

Cryptography in World War II Jefferson Institute for Lifelong Learning at UVa Spring 2006 David Evans Menu Class 4: • Some loose ends on WWII Modern •Maurice Burnett Cryptography • Modern Cryptography – Modern symmetric ciphers – Public-key cryptosystems http://www.cs.virginia.edu/jillcrypto JILL WWII Crypto Spring 2006 - Class 4: Modern Cryptography 2 British Cipher Machine German Code-Breaking Efforts • Design based on commercial Enigma • About 6,000 people (compare to 12,000 working at Bletchley Park) • 5 rotor wheels (instead • Decentralized: each military branch had of 3 in Enigma) their own, didn’t share what they learned • Multiple rings per rotor • Effective against manual codes: broke • Last 2 rotor wheels about 50% of manually coded messages didn’t rotate • Didn’t attempt to break rotor-based • British attempted to ciphers – so confident Enigma was break it (without unbreakable, didn’t try to Typex and success) similar machines Typex Machine JILL WWII Crypto Spring 2006 - Class 4: Modern Cryptography 3 JILL WWII Crypto Spring 2006 - Class 4: Modern Cryptography 4 Lorenz Cipher From http://www.codesandciphers.org.uk/lorenz/fish.htm JILL WWII Crypto Spring 2006 - Class 4: Modern Cryptography 5 JILL WWII Crypto Spring 2006 - Class 4: Modern Cryptography 6 1 Modern Symmetric Ciphers Modern Ciphers A billion billion is a large number, but it's not that large a number. Whitfield Diffie • AES (Rijndael) successor to DES selected 2001 • Same idea but: • 128-bit keys, encrypt 128-bit blocks –Use digital logic instead of • Brute force -

The Government Machine a Revolutionary History of the Computer

The Government Machine History of Computing I. Bernard Cohen and William Aspray, editors Jon Agar, The Government Machine: A Revolutionary History of the Computer William Aspray, John von Neumann and the Origins of Modern Computing Charles J. Bashe, Lyle R. Johnson, John H. Palmer, and Emerson W. Pugh, IBM’s Early Computers Martin Campbell-Kelly, From Airline Reservations to Sonic the Hedgehog: A History of the Software Industry Paul E. Ceruzzi, A History of Modern Computing I. Bernard Cohen, Howard Aiken: Portrait of a Computer Pioneer I. Bernard Cohen and Gregory W. Welch, editors, Makin’ Numbers: Howard Aiken and the Computer John Hendry, Innovating for Failure: Government Policy and the Early British Computer Industry Michael Lindgren, Glory and Failure: The Difference Engines of Johann Müller, Charles Babbage, and Georg and Edvard Scheutz David E. Lundstrom, A Few Good Men from Univac René Moreau, The Computer Comes of Age: The People, the Hardware, and the Software Emerson W. Pugh, Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology Emerson W. Pugh, Memories That Shaped an Industry Emerson W. Pugh, Lyle R. Johnson, and John H. Palmer, IBM’s 360 and Early 370 Systems Kent C. Redmond and Thomas M. Smith, From Whirlwind to MITRE: The R&D Story of the SAGE Air Defense Computer Raúl Rojas and Ulf Hashagen, editors, The First Computers—History and Architectures Dorothy Stein, Ada: A Life and a Legacy John N. Vardalas, The Computer Revolution in Canada: Building National Technological Competence Maurice V. Wilkes, Memoirs of a Computer Pioneer The Government Machine A Revolutionary History of the Computer Jon Agar The MIT Press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England © 2003 Massachusetts Institute of Technology All rights reserved. -

Some Aspects of Cryptographic Protocols

Some aspects of cryptographic protocols with applications in electronic voting and digital watermarking BJÖRN TERELIUS Doctoral Thesis Stockholm, Sweden 2015 TRITA CSC 2015:08 KTH ISSN 1653-5723 School of Computer Science and Communication ISRN KTH/CSC/A--15/08--SE SE-100 44 Stockholm ISBN 978-91-7595-545-2 SWEDEN Akademisk avhandling som med tillstånd av Kungl Tekniska högskolan framläg- ges till offentlig granskning för avläggande av teknologie doktorsexamen i datalogi den 22 maj 2015 klockan 14:00 i Kollegiesalen, Administrationsbyggnaden, Kungl Tekniska högskolan, Valhallavägen 79, Stockholm. © Björn Terelius, May 2015 Tryck: Universitetsservice US AB iii Abstract Cryptographic protocols are widely used on the internet, from relatively simple tasks such as key-agreement and authentication to much more com- plex problems like digital cash and electronic voting. Electronic voting in particular is a problem we investigate in this thesis. In a typical election, the main goals are to ensure that the votes are counted correctly and that the voters remain anonymous, i.e. that nobody, not even the election authorities, can trace a particular vote back to the voter. There are several ways to achieve these properties, the most general being a mix-net with a proof of a shuffle to ensure correctness. We propose a new, conceptually simple, proof of a shuffle. We also investigate a mix-net which omits the proof of a shuffle in favor of a faster, heuristically secure verification. We demonstrate that this mix-net is susceptible to both attacks on correctness and anonymity. A version of this mix-net was tested in the 2011 elections in Norway.