Peace Operations in Africa Operations Peace

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vol. II: Anns. 1-29

Note: This translation has been prepared by the Registry for internal purposes and has no official character 14579 Corr. INTERNATIONAL COURT OF JUSTICE CASE CONCERNING IMMUNITIES AND CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS (EQUATORIAL GUINEA v. FRANCE) MEMORIAL OF THE REPUBLIC OF EQUATORIAL GUINEA VOLUME II (Annexes 1-29) 3 January 2017 [Translation by the Registry] LIST OF ANNEXES Annex Page 1. Basic Law of Equatorial Guinea (new text of the Constitution of Equatorial 1 Guinea, officially promulgated on 16 February 2012, with the texts of the Constitutional Reform approved by referendum on 13 November 2011) 2. Regulation No. 01/03-CEMAC-UMAC of the Central African Economic and 43 Monetary Community 3. Decree No. 64/2012, 21 May 2012 44 4. Decrees Nos. 67/2012, 66/2012, 65/2012 and 63/2012, 21 May 2012 46 5. Institutional Declaration by the President of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, 47 21 October 2015 6. Presidential Decree No. 55/2016, 21 June 2016 49 7. Paris Tribunal de grande instance, Order for partial dismissal and partial 51 referral of proceedings to the Tribunal correctionnel, 5 September 2016 (regularized by order of 2 December 2016) 8. Paris Tribunal de grande instance, Public Prosecutor’s Office, Application for 88 characterization, 4 July 2011 9. Report of the Public Prosecutor of the Republic of Equatorial Guinea, 91 22 November 2010 10. Summons to attend a first appearance, 22 May 2012 93 11. French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Note Verbale No. 2777/PRO/PID, 96 20 June 2012 12. Letter from the investigating judges to the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, 98 25 June 2012 13. -

A Abbe Diamacoune, 114 Abduction of Girl-Children, 155 Abidjan Accord

Index A African body politic and purge elite Abbe Diamacoune, 114 domination, xxiii Abduction of girl-children, 155 African indigenous associational life, Abidjan Accord (November 30, 1996), xix 320 Africa-led International Support Abubakar, Abdusalami, 57, 198, 225 Mission to Mali (AFISMA), 312, Abuja Accord (August 1995), 195, 202 313 Abuja Accord (August 1996), 195 African organizations, 311 Abuja II Accord (effect in 1997), 196 African Union (AU), xxv, 2, 13, 17, Abusive-aggressive policing, 86 25, 35, 40, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, 61, Access to education, xxvi, 17, 93, 94, 62, 65, 70, 71, 73, 131, 163, 165, 265 166, 192, 220, 225, 258, 267, Access to formal education, 89 311, 313 Accords (Foundiougne I, February African Union’s principle of non- 2005; Foundiougne II, December, indifference, 299 2005), 129 African Women’s Committee for Peace 2003 Accra Agreement, 198 and Development, the, 164 Accra Clarification (December 1994), African youth, 83, 92, 103 195 African Youth Charter, 95 Addictive substances, 88 Ag Bamoussa, 309 Affirmative action, 125 Agenda for Development (1994), 322 Afolabi, Babatunde, xvii, xviii, 21, 22 Agenda for Peace, 7, 234, 322 AFRC-RUF Coalition Government, Ag Mbarek Kay, 309 315 Ag Mohamed Najem, 309 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2020 337 O. Akiba (ed.), Preventive Diplomacy, Security, and Human Rights in West Africa, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-25354-7 338 INDEX Agre, Bernard, Cardinal (late), 232 Aristotle, xxi, xxvii Agricultural land-use, 137 Armed Forces of Liberia (AFL), 177, Ahmed -

Defense Cooperation, the Status of United States Forces, and Access to and Use of Agreed Facilities and Areas in the Republic of Senegal

TREATIES AND OTHER INTERNATIONAL ACTS SERIES 16-812 ________________________________________________________________________ DEFENSE Cooperation Agreement Between the UNITED STATES OF AMERICA and SENEGAL Signed at Dakar May 2, 2016 with Annex and Appendices NOTE BY THE DEPARTMENT OF STATE Pursuant to Public Law 89—497, approved July 8, 1966 (80 Stat. 271; 1 U.S.C. 113)— “. .the Treaties and Other International Acts Series issued under the authority of the Secretary of State shall be competent evidence . of the treaties, international agreements other than treaties, and proclamations by the President of such treaties and international agreements other than treaties, as the case may be, therein contained, in all the courts of law and equity and of maritime jurisdiction, and in all the tribunals and public offices of the United States, and of the several States, without any further proof or authentication thereof.” SENEGAL Defense: Cooperation Agreement signed at Dakar May 2, 2016; Entered into force August 12, 2016. With annex and appendices. AGREEMENT BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AND THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL ON DEFENSE COOPERATION, THE STATUS OF UNITED STATES FORCES, AND ACCESS TO AND USE OF AGREED FACILITIES AND AREAS IN THE REPUBLIC OF SENEGAL Preamble The United States of America (hereinafter "the United States") and the Republic of Senegal (hereinafter "Senegal"), hereinafter referred to collectively as "the Parties" and singularly as a "Party"; Desiring to enhance security cooperation between the Parties and recognizing that -

Religion and Violence

Religion and Violence Edited by John L. Esposito Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions John L. Esposito (Ed.) Religion and Violence This book is a reprint of the special issue that appeared in the online open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) in 2015 (available at: http://www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special_issues/ReligionViolence). Guest Editor John L. Esposito Georgetown University Washington Editorial Office MDPI AG Klybeckstrasse 64 Basel, Switzerland Publisher Shu-Kun Lin Assistant Editor Jie Gu 1. Edition 2016 MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan ISBN 978-3-03842-143-6 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-03842-144-3 (PDF) © 2016 by the authors; licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. All articles in this volume are Open Access distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution license (CC-BY), which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles even for commercial purposes, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. However, the dissemination and distribution of physical copies of this book as a whole is restricted to MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. III Table of Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................... V Preface ............................................................................................................................... VII Jocelyne Cesari Religion and Politics: What Does God Have To Do with It? Reprinted from: Religions 2015, 6(4), 1330-1344 http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/6/4/1330 ............................................................................ 1 Mark LeVine When Art Is the Weapon: Culture and Resistance Confronting Violence in the Post-Uprisings Arab World Reprinted from: Religions 2015, 6(4), 1277-1313 http://www.mdpi.com/2077-1444/6/4/1277 ......................................................................... -

Senegambian Confederation: Prospect for Unity on the African Continent

NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law Volume 7 Number 1 Volume 7, Number 1, Summer 1986 Article 3 1986 SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/ journal_of_international_and_comparative_law Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation (1986) "SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT," NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law: Vol. 7 : No. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/journal_of_international_and_comparative_law/vol7/iss1/3 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Journal of International and Comparative Law by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. NOTE SENEGAMBIAN CONFEDERATION: PROSPECT FOR UNITY ON THE AFRICAN CONTINENT* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ............................................ 46 II. THE SHADOW OF CONFEDERATION .......................... 47 A. Debate on the Merits of a Union: 1960-81 ......... 47 B. Midwife to Confederation: 1981 Coup Attempt in The G ambia ... .. ............................ 56 III. THE SUBSTANCE OF CONFEDERATION ........................ 61 A. Introduction to the Foundation Document and Pro- to co ls . 6 1 B. Defense of The Confederation and Security of Mem- ber S ta tes ...................................... 65 C. Foreign Policy of the Confederation and Member S tates . .. 6 9 D. Unity of Member Nations' Economies and Confed- eral F inance .................................... 71 1. Econom ic Union ............................. 71 2. Confederal Finance .......................... 76 E. Confederal Institutions and Dispute Resolution ... 78 1. Institutions ................................. 78 2. Dispute Resolution ........................... 81 IV. REACTION TO THE CONFEDERATION ................... 82 V. FUTURE PROSPECTS: CONFEDERATION LEADING TO FEDERA- TIO N ? . .. .. 8 4 V I. -

Conflict and Peace in Casamance

MAR CH 2 0 2 0 LASPAD WORKING PAPER N°1 MAME - PENDA BA & RACHID ID YASSINE CONFLICT AND PEACE IN CASAMANCE Voices of Senegalese, Gambian and Bissau-Guinean citizens www.casamance - conflict.com www.laspad.org 0 www.casamance - conflict.com LASPAD, Saint-Louis, March 2020 This document was written by Mame-Penda Ba and Rachid Id Yassine. This document is part of a series of texts intended to contribute to reflections and actions in favor of the resolution of the conflict in Casamance and more broadly of all those which take place on the African continent. This report is part of the research activities of the collaborative working group entitled "From" No War, No Peace "to Peacebuilding in Casamance? ", From the African Peacebuilding Network funded by the Social Science Research Council (United States). It also received support from the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation (Germany). Let these partners be thanked for making scientific work possible through their support. The authors thank all the team members, the researchers, investigators and assistants who participated in the research, as well as all the experts who contributed to the activities of the program: Abdu Ndukur Ndao, Aïda Diop, Bocar Guiro, Bodian Diatta, Bruno Sonko, Cheikh Ahmed Tidiane Mbow, Diouma Dia, El Hadj Malick Ndiaye, El Hadj Malick Sané, El Hadj Malick Sy Gaye, Ensa Kujabi, Eugène Tavares, Fatimatou Dia, Fortune Mendy Diatta, Françoise MCP Rodrigues, Jean-Alain Goudiaby, Joao Paulo Pinto Co, Karamba Jallox, Khadidiatou Dia, Khalifa Diop, Laia Cassama, Landing Goudiaby, Mamady Diémé, Mamoudou Sy, Moïse Diédhiou, Monica Labonia, Mouhamed Lamine Manga, Moustapha Guéye, Ndeye Khady Anne, Nyimasata Camaraé, Pape Chérif Diédhiou, Saït Matty Jaw, Valentina Ramos Sambe. -

Volume 9 1982 Issue 24

Number 24 Contents May-August 1982 Editorial 1 Editorial Working Group Chris Allen Political Graft and the Spoils Carol Barker Carolyn Baylies System in Zambia Lionel Cliffe Morris Szeftel 4 Robin Cohen Erica Flegg Class Struggles in Mali Shubi Ishemo Peter Lawrence Pierre Francois 22 Jitendra Mohan (Book Reviews) Barry Munslow The Algerian Bureaucracy Penelope Roberts Francis Snyder Hugh Roberts 39 Morris Szeftel Gavin Williams French Militarism in Africa Editorial Staff Robin Luckham 55 Doris Burgess Judith Mohan Briefings 85 Overseas Editors Fishing Co-ops on Lake Niassa; Cairo: Shahida El Baz The Workers Struggle in South Copenhagen: Roger Leys Africa; Where does FOSATU Canberra (Aust): Dianne Bolton stand?; Mozambique's Kampala: Mahmood Mamdani Khartoum: Ibrahim Kursany Agricultural Policy; Namibia Oslo: Tore Linné Eriksen and Lesotho's Massacre's Stockholm: Bhagavan Toronto: Jonathan Barker, John Saul Current Africana 123 Washington: Meredeth Turshen Zaria: Bjorn Beckman Contributing Editors Jean Copans Basil Davidson Mejid Hussein This publication is indexed in the Alternative Duncan Innes Press Index, Box 7279, Baltimore, MD 21218, Charles Kallu-Kalumiya USA. Mustafa Khogali Colin Leys Robert Van Lierop Archie Mafeje Prexy Nesbitt Claude Meillassoux Ken Post Subscriptions (3 issues) UK & Africa 1 yr 2 yrs Individual £6 £11 Institution £14 £25 Elsewhere Individual £7/$15 £12.50/$24 Institution £16/$35 £25/$60 Students £4.50 ,(sterling only) Airmail extra (per 3 issues) Europe £3.00 Elsewhere £5.00 Giro no. 64 960 4008 Subscription to Copyright ©Review of African Political Review of African Political Economy, Economy, December 1982 341 Glossop Road, Sheffield S10 2HP, ISSN: 0305 6244 England. -

Regional Seminar for Countries in Central, Northern and Western Africa

EUROPEAN UNION UNITED NATIONS INSTITUTE FOR DISARMAMENT RESEARCH Téléphone : + 41 (0)22 917 20 90 PALAIS DES NATIONS – A.509 Téléfax : + 41 (0)22 917 01 76 CH-1211 GENÈVE 10 [email protected] SWITZERLAND www.unidir.org Geneva, 2 June 2009 Promoting Discussion on an Arms Trade Treaty European Union–UNIDIR Project Regional Seminar for Countries in Central, Northern and Western Africa 28–29 April 2009 Dakar, Senegal SUMMARY REPORT Table of contents Introduction ................................................................................................................ 3 Presentations and discussions...................................................................................... 3 Opening presentations.............................................................................................. 3 General overview of arms transfers and the proposed ATT ...................................... 5 Regional perspectives on an ATT ............................................................................ 6 Human security and a possible ATT......................................................................... 7 Working groups and roundtable discussions............................................................. 7 Closing session ........................................................................................................ 8 Recommendations and ideas .......................................................................................8 An ATT should be based on globally accepted parameters...................................... -

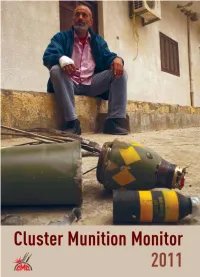

Cluster Munition Monitor 2011

Cluster Munition Monitor 2011 Editorial Board Mines Action Canada • Action on Armed Violence • Handicap International Human Rights Watch • Norwegian People’s Aid © October 2011 by Mines Action Canada All rights reserved Printed and bound in Canada ISBN: 978-0-9738955-9-9 Cover photograph © André Liohn/Human Rights Watch, April 2011 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor provides research and monitoring for the Cluster Munition Coalition (CMC) and the International Campaign to Ban Landmines (ICBL)and is a formal program of the ICBL-CMC. For more information visit www.the-monitor.org or email [email protected]. Landmine and Cluster Munition Monitor makes every effort to limit the environmental footprint of reports. This report is printed on paper containing post-consumer recycled waste fiber. Biogas Energy, an energy source produced from decomposing waste collected from landfill sites, was used in paper production to reduce greenhouse emissions and depletion of the ozone layer. Using 2,720.4kg of this paper instead of paper made from virgin fibers saves 51.6 mature trees, 1,470kg of solid waste, 139,056l of water, and 3,228kg of air emissions. Our printer, St. Joseph Communications, is certified by the EcoLogo Environmental Choice Program. St. Joseph Communications uses vegetable-based inks that are less toxic than chemical inks, and runs the Partners in Growth Program. For every ton of paper used on our behalf, they contribute three seedlings to Scouts Canada for planting in parks, recreation and conservation areas, and other public spaces across Canada. Since its inception, the program has planted more than two million trees. -

Integrating Gender in Security Sector Reform and Governance

Tool 8 Integrating Gender in Security Sector Reform and Governance Aisha Fofana Ibrahim, Alex Sivalie Mbayo, Rosaline Mcarthy Toolkit for Security Sector Reform and Governance in West Africa Integrating Gender in Security Sector Reform and Governance Aisha Fofana Ibrahim, Alex Sivalie Mbayo, Rosaline Mcarthy Toolkit for Security Sector Reform and Governance in West Africa About the authors Dr Aisha Fofana Ibrahim is a feminist scholar and activist. She is the Director of the Institute for Gender Research and Documentation (INGRADOC), Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone and president of the 50/50 Group of Sierra Leone, with over 20 years of experience teaching and researching gender, literature, and peace-building. She also has vast experience working on gender and security sector reform and has worked extensively with the Sierra Leone Police as a consultant for DCAF. Her current research interests include women’s political participation, quotas, and gender and security sector reform. Dr Alex Sivalie Mbayo is a lecturer at the Department of Peace and Conflict Studies and INGRADOC, Fourah Bay College, University of Sierra Leone. His academic research focuses mainly on gender, human rights, and development issues and also includes gender mainstreaming in peacekeeping operations and in post-conflict peace-building. He holds a master’s degree in Gender and Peacebuilding, a post-graduate diploma in Refugee Studies from the UN Mandated University for Peace, Costa Rica, and a PhD in Gender and Peacebuilding from Hiroshima University, Japan. Ms Rosaline Mcarthy is an academic and gender activist with nearly 20 years of experience in training and research on peace and security, reparations for victims of sexual violence during conflict, and gender equality and human rights issues. -

Syed Dissertation Final 2

Al-ḤājjʿUmar Tāl and the Realm of the Written: Mastery, Mobility and Islamic Authority in 19th Century West Africa by Amir Syed A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology and History) in the University of Michigan 2017 Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Rudolph T. Ware, Chair Professor Paul Johnson Professor Rüdiger Seesemann, University of Bayreuth Professor Andrew Shryock Dedication To my parents, Safiulla and Fazalunissa, for bringing me here; And to Shafia, Neha, and Lina, for continuing to enrich me ii Acknowledgements It is overwhelming to think about the numerous people who made this journey possible; from small measures of kindness, generosity and assistance, to critical engagement with my ideas, and guiding my intellectual development. Words cannot capture the immense gratidue that I feel, but I will try. I would never have become a historian without the fine instruction I received from the professors at the University of British Columbia. From among them, I will single out Paul Lewin Krause, whose encouragement and support first put me on this path to scholarship. His lessons on writing and teaching are a treasure trove that, so many years later, I continue to draw from. By coming to the University of Michigan, I found a new set of professors, colleagues, and friends. Through travel and intellectual engagement, away from Ann Arbor, I also met many others who have helped me over the years. I would like to first thank my committee members for helping me see this project through. Over numerous years, and perhaps hundreds of conversations, my advisor, Butch Ware, helped me develop my ideas, and get them onto paper. -

UNOWAS E-Magazine ISSUE 2

UNOWAS E-Magazine N2 Quarterly E-Magazine of the United Nations Office for West Africa and the Sahel l Together for Peace IN THIS ISSUE Focus The United Nations’ support to tackle insecurity in Lake UNOWAS, MISAHEL, Lake Chad Basin Chad Basin Commission and The Multinational Joint Task Force discuss the security Since 2009, when the erstwhile leader of Boko Haram Mohammed Yusuf died in police custody, the level of killings and destruction, enslavement of girls and situation of the region women, and the loss of livelihoods inflicted by the group has caught the world’s attention. In response, the United Nations has adopted an approach that- at tempts to bring together the organization’s vast experience...Read more P.3 Baga-Sola (Lake Chad) Few fishermen dare venture on the waters of the Lake since the beginning of the Nigerian crisis. Crédit: UN CHAD As part of his joint visit in Chad with President Buyoya, Head of the African Union Mission for Mali and the Sahel (MISAHEL)...Read more P.4 West Africa and the Sahel, key topics of the 71st United Nations General UNOWAS delegation meeting with the Nigerian Air Force HQ in Abuja © UNOWAS Assembly Session Editorial “Not to take our eyes off the ball” By Mohamed Ibn Chambas t is well known that the overall humanitarian assistance across the security situation in the Lake region, including 7 million that are Nigerian refugees arrive on Lake Chad islands in Niger. (UNHCR partner in south Niger) / September 2014 Chad Basin area remains severely food insecure, and about precarious and volatile.