Downloaded From: Usage Rights: Creative Commons: Attribution-Noncommercial-No Deriva- Tive Works 4.0

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fieldstudy 16. from a Distance

[1] FIELDSTUDY 16 FIELDSTUDY 16 FROM A DISTANCEREAS PAUL [3] FIELDSTUDY 16 FROM A FIELDSTUDY 16 DISTANCEREAS PAUL Millions of people pass through the Elephant and Castle and its maze of roundabouts without ever noticing the people who live there. It is a place to get through, a place on the way to somewhere else. Of course, it could be argued that there is a certain reality to all of this. After all, the Elephant has one of the most transitory populations in London. Many do not settle here for long. Even the people who live here are on the move. The buildings look sharp And a photographer who but the people are blurred could set the time exposure into traces of movement, as on her camera for a century if they were ghosts. I have or so would register little that something of a problem is permanent. This is a place with our fascination with with a continual history of long exposure photography. dramatic change: from the got to the point where they Slowing down the shutter bustling and fashionable can only see from a distance: speed captures what is 1930’s with its picture houses the sort of distance from permanent but obscures and mega-churches, through which you can’t see a face, what is transient. It is a the devastation of the Nazi meet the eyes of someone, technique can generate bombings, and on to the hear who they are, imagine all sorts of exciting visual construction of large scale who and what they love. All effects, especially in cities. -

A Green and Pleasant Land British Landscape and the Imagination: 1970S to Now 30 September 2017 – 21 January 2018

A GREEN AND PLEASANT LAND British Landscape and the Imagination: 1970s to Now 30 September 2017 – 21 January 2018 An Arts Council Collection National Partner Exhibition TO VIEW THE LANDSCAPE AS A PICTORIAL COMPOSITION OF ELEMENTS IS SIMPLISTIC. TO PERCEIVE THE LANDSCAPE WITHIN A SET OF RULES (art, SCIENCE, POLITICS, RELIGION, COMMUNITY, BUSINESS, INDUSTRY, sport AND LEISURE) IS A waY PEOPLE CAN DEAL WITH THE COMPLEXITY OF MEANINGS THat ARE PRESENTED IN OUR ENVIRONMENT. WE ARE COLLECTIVELY RESPONSIBLE FOR SHAPING THE LANDSCAPE WE OCCUPY AND IN TURN THE LANDSCAPE Cover: Keith Arnatt, Untitled (from ‘A.O.N.B’ SHAPES US WHETHER series), 1982-94. Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London © Keith Arnatt WE ARE awarE OF Estate. All rights reserved. DACS 2017. IT OR NOT. Above: Susan Derges, Full Moon Rowan, 2017. © Susan Derges. Courtesy Purdy Hicks Gallery. John Davies. Photographer A Green and Pleasant Land shows how artistic sensibilities result from feeling the artists have interpreted the British landscape presence of the earth. Light, texture and through the lens of their own cultural, detail are important and viewpoints are political or spiritual principles. Drawn often close. On the other hand, artists primarily from the Arts Council Collection, commenting on the ways in which class, as well as private collections, galleries economics and culture shape the landscape and the artists included in the show, the tend to look from the outside. Their work exhibition takes 1970 as its starting point is often expansive and encompasses clear and consists largely of photographic works. evidence of human activity – people, The early 1970s saw the emergence of an buildings, ruins, pylons – suggesting the independent photography culture in the UK. -

Download Publication

CONTENTS History The Council is appointed by the Muster for Staff The Arts Council of Great Britain wa s the Arts and its Chairman and 19 othe r Chairman's Introduction formed in August 1946 to continue i n unpaid members serve as individuals, not Secretary-General's Prefac e peacetime the work begun with Government representatives of particular interests o r Highlights of the Year support by the Council for the organisations. The Vice-Chairman is Activity Review s Encouragement of Music and the Arts. The appointed by the Council from among its Arts Council operates under a Royal members and with the Minister's approval . Departmental Report s Charter, granted in 1967 in which its objects The Chairman serves for a period of five Scotland are stated as years and members are appointed initially Wales for four years. South Bank (a) to develop and improve the knowledge , Organisational Review understanding and practice of the arts , Sir William Rees-Mogg Chairman Council (b) to increase the accessibility of the art s Sir Kenneth Cork GBE Vice-Chairma n Advisory Structure to the public throughout Great Britain . Michael Clarke Annual Account s John Cornwell to advise and co-operate wit h Funds, Exhibitions, Schemes and Awards (c) Ronald Grierson departments of Government, local Jeremy Hardie CB E authorities and other bodies . Pamela, Lady Harlec h Gavin Jantje s The Arts Council, as a publicly accountable Philip Jones CB E body, publishes an Annual Report to provide Gavin Laird Parliament and the general public with an James Logan overview of the year's work and to record al l Clare Mullholland grants and guarantees offered in support of Colin Near s the arts. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

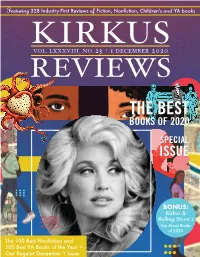

Kirkus Best Books of 2020

Featuring 328 Industry-First Reviews of Fiction, Nonfiction, Children'sand YA books KIRKUSVOL. LXXXVIII, NO. 23 | 1 DECEMBER 2020 REVIEWS THE BEST BOOKS OF 2020 SPECIAL ISSUE BONUS: Kirkus & Rolling Stone’s Top Music Books of 2020 The 100 Best Nonfiction and 100 Best YA Books of the Year + Our Regular December 1 Issue from the editor’s desk: Books That Deserved More Buzz Chairman HERBERT SIMON President & Publisher BY TOM BEER MARC WINKELMAN # Chief Executive Officer MEG LABORDE KUEHN [email protected] John Paraskevas Editor-in-Chief Every December, I look back on the year past and give a shoutout to those TOM BEER books that deserved more buzz—more reviews, more word-of-mouth [email protected] Vice President of Marketing promotion, more book-club love, more Twitter excitement. It’s a subjec- SARAH KALINA tive assessment—how exactly do you measure buzz? And how much is not [email protected] Managing/Nonfiction Editor enough?—but I relish the exercise because it lets me revisit some titles ERIC LIEBETRAU that merit a second look. [email protected] Fiction Editor Of course, in 2020 every book deserved more buzz. Between the pan- LAURIE MUCHNICK demic and the presidential election, it was hard for many titles, deprived [email protected] Young Readers’ Editor of their traditional publicity campaigns, to get the attention they needed. VICKY SMITH A few lucky titles came out early in the year, disappeared when coronavi- [email protected] Tom Beer Young Readers’ Editor rus turned our world upside down, and then managed to rebound; Douglas LAURA SIMEON [email protected] Stuart’s Shuggie Bain (Grove, Feb. -

This Book Is a Compendium of New Wave Posters. It Is Organized Around the Designers (At Last!)

“This book is a compendium of new wave posters. It is organized around the designers (at last!). It emphasizes the key contribution of Eastern Europe as well as Western Europe, and beyond. And it is a very timely volume, assembled with R|A|P’s usual flair, style and understanding.” –CHRISTOPHER FRAYLING, FROM THE INTRODUCTION 2 artbook.com French New Wave A Revolution in Design Edited by Tony Nourmand. Introduction by Christopher Frayling. The French New Wave of the 1950s and 1960s is one of the most important movements in the history of film. Its fresh energy and vision changed the cinematic landscape, and its style has had a seminal impact on pop culture. The poster artists tasked with selling these Nouvelle Vague films to the masses—in France and internationally—helped to create this style, and in so doing found themselves at the forefront of a revolution in art, graphic design and photography. French New Wave: A Revolution in Design celebrates explosive and groundbreaking poster art that accompanied French New Wave films like The 400 Blows (1959), Jules and Jim (1962) and The Umbrellas of Cherbourg (1964). Featuring posters from over 20 countries, the imagery is accompanied by biographies on more than 100 artists, photographers and designers involved—the first time many of those responsible for promoting and portraying this movement have been properly recognized. This publication spotlights the poster designers who worked alongside directors, cinematographers and actors to define the look of the French New Wave. Artists presented in this volume include Jean-Michel Folon, Boris Grinsson, Waldemar Świerzy, Christian Broutin, Tomasz Rumiński, Hans Hillman, Georges Allard, René Ferracci, Bruno Rehak, Zdeněk Ziegler, Miroslav Vystrcil, Peter Strausfeld, Maciej Hibner, Andrzej Krajewski, Maciej Zbikowski, Josef Vylet’al, Sandro Simeoni, Averardo Ciriello, Marcello Colizzi and many more. -

The New Front Line

PRESS RELEASE Phillips Partners with British Vogue to Present The New Front Line A Virtual Selling Exhibition Premiering 27 Photographs by Jamie Hawkesworth Taken for British Vogue’s July Issue Proceeds to Benefit National Emergencies Trust Jamie Hawkesworth, Anisa Omar, Waitrose & Partners Assistant and Karrie Scott, Postal worker, 24 © Jamie Hawkesworth LONDON – 13 JULY 2020 – This July, in collaboration with British Vogue, Phillips will premiere the work of celebrated photographer Jamie Hawkesworth in a virtual selling exhibition The New Front Line. Hawkesworth has selected 27 unique works to be made available for sale for the first time, with all proceeds going to the National Emergencies Trust. The portraits hail from his recent portfolio of front-line workers in the Covid-19 effort, which includes the iconic cover story for British Vogue’s July 2020 issue. These unique works will be available for sale on Phillips.com as part of a virtual exhibition, running from 14 to 28 July 2020. Edward Enninful, Editor in Chief of British Vogue, said, “I am delighted that Jamie Hawkesworth's images of our key workers are going to be included in this important exhibition at Phillips. Vogue’s July cover stars celebrate a moment in time when millions of people in the UK who, at the height of the pandemic, in the face of dangers large and small, put on their uniforms and work clothes and went to help people." Jamie Hawkesworth, said, “I spent two weeks on this project and the most joyous thing about it has been the time I spent with each person I photographed. -

Introduction

Introduction Martin Parr is a chronicler of our age. In the face of the constantly growing flood of images released by the media, his photographs offer us the opportunity to see the world from his unique perspective. At first glance, his photographs seem exaggerated or even grotesque. The motifs he chooses are strange, the colours are garish and the perspectives are unusual. Parr's term for the overwhelming power of published images is "propaganda". He counters this propaganda with his own chosen weapons: criticism, seduction and humour. As a result, his photographs are original and entertaining, accessible and understandable. But at the same time they show us in a penetrating way that we live, how we present ourselves to others, and what we value. Leisure, consumption and communication are the concepts that this British photographer has been researching for several decades now on his worldwide travels. In the process, he examines national characteristics and international phenomena to find out how valid they are as symbols that will help future generations to understand our cultural peculiarities. Parr enables us to see things that have seemed familiar to us in a completely new way. In this way he creates his own image of society, which allows us to combine an analysis of the visible signs of globalisation with unusual visual experiences. In his photos, Parr juxtaposes specific images with universal ones without resolving the contradictions. Individual characteristics are accepted and eccentricities are treasured. The themes Parr selects and his inimitable treatment of them set him apart as a photographer whose work involves the creation of extensive series. -

Curating the Space Magazines Next Generation Technology Matters Please Enjoy This Preview of Our Latest Issue

#29 What’s Next? Winter 2011/2012 €17,50 Independent From Here On(line) Curating the Space Magazines Next Generation Technology Matters Please enjoy this preview of our latest issue. We encourage you to visit our shop and purchase or subscribe to the magazine to get the full experience. Independent From Here On(line) Curating the Space Next Generation Technology Matters and more... foam magazine # 29 what's next? 4 Ten years ago What’s next? What’s In December 2001, a new photography next after I have finished museum opened its doors in Amsterdam – Foam was born. At the same time, a new what I am doing right photography magazine was launched: Foam Magazine started out as a catalogue now? What’s next for me accompanying the first exhibition, but tomorrow, at the begin- immediately became an independent platform for photography. This year marks ning of a brand new the tenth anniversary of both Foam and Foam Magazine – a memorable event that day? What’s next for you, deserves to be celebrated. However, just for us? Promises, expec- looking back and congratulating ourselves on what has been achieved over the tations, hopes and ideas past decade doesn’t fit the mindset that is characteristic of our staff. Our curiosity about what is in the about new developments is simply stronger pipeline are often very than our desire to look back. And so the What’s Next? theme arose naturally for our influential on the way we jubilee year. think, feel or behave. The fact that we found this a fitting theme to reaffirm our ten-year anniversary What’s next? It’s a simple indicates a validation of the current question that can be position of photography. -

“Highlights of a Trip to Hell” Contextualizing the Initial

“Highlights Of A Trip To Hell” Contextualizing the Initial Reception of Larry Clark’s Tulsa by William T. Green A thesis project presented to Ryerson University and George Eastman House, Intentional Museum of Photography in Film In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Photographic Preservation and Collections Management Rochester, New York, United States and Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2013 © William T. Green 2013 Author’s Declaration I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this thesis to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. William T. Green I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this thesis by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. William T. Green ii Abstract Released in 1971, Tulsa, American artist Larry Clark’s career-launching first photobook, is today remembered as marking a watershed moment in American photography. This paper travels back to the era that Tulsa was first published to examine the book’s initial critical reception and significance within that specific cultural and artistic climate. It presents an abbreviated overview of Tulsa’s gradual creation; illustrates the ways in which the book was both similar to and different from other commonly cited contemporaneous works; and surveys its evolving status and reputation throughout the 1970s and into the early 1980s, when its second edition was published. -

TBN12.Pdf Murray and Robert Parkinson in June 2009

The Blue Notebook Volume 6 No.2 April 2012 1 The Blue Notebook is published in two formats: an online colour version, and a paper, black and white version. An annual subscription covers both formats for two issues, UK or international. For subscriptions, please download the form on our publications page: www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/bnotebk.htm or contact us for a postal form. We welcome submissions of writing on contemporary artists’ books and related issues for The Blue Notebook. Please email [email protected] for guidelines or see: www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk/bnotebk.htm Artists’ contributions are by invitation from the Art Editor, Tom Sowden. The Blue Notebook journal for artists’ books is published by Wild Conversations Press, Bristol www.wildconversations.isophia.co.uk Editor: Sarah Bodman Art Editor: Tom Sowden Design: Sarah Bodman and Tom Sowden Cover design: Tom Sowden Editorial address: Impact Press at the Centre for Fine Print Research UWE Bristol, Kennel Lodge Road, Bristol, BS3 2JT, UK Tel: +44 (0)117 328 4915 Fax: +44 (0)117 328 5865 [email protected] [email protected] www.bookarts.uwe.ac.uk The Blue Notebook Vol.6 No.2 April 2012 ISSN 1751-1712 (print) ISSN 1751-1720 (online) © 2012 publication, Impact Press © 2012 texts, individual authors © 2012 images, individual artists Permission to photocopy texts for personal use, one-off educational use in study packs, or for individual academic study is granted. For any other use, please contact the editor and the individual author or artist for their authorisation. -

Intersections, Boundaries and Passages

Keith Dietrich INTERSECTIONS, BOUNDARIES AND PASSAGES: TRANSGRESSING THE CODEX October 2011 Keith Dietrich was born in Johannesburg in 1950 and studied graphic design at Stellenbosch University, where he graduated with a BA degree in Visual Arts in 1974. Between 1975 and 1977 he studied painting at the National Higher Institute for Fine Arts in Antwerp, Belgium. He obtained his MA in Fine Arts (cum laude) in 1983 and his D Litt et Phil in Art History in 1993, both at the University of South Africa (Unisa). He has lectured at the University of Pretoria and Unisa, and is currently INTRODUCTION Chair of the Department of Visual Arts at Stellenbosch University. He has participated in over thirty community interaction projects in southern Africa and has received a number of awards, in South Africa and abroad, for both his creative and his academic work. He has participated in group exhibitions and biennials in Belgium, Botswana, Chile, Egypt, Germany, Italy, Namibia, the Netherlands, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the USA, and has held 20 solo exhibitions in South Africa. His work is represented in 34 corporate and public collections in South Africa and abroad. 1 Intersections, Boundaries and Passages: Transgressing the Codex Inaugural lecture presented on 4 October 2011 Prof. K.H. Dietrich Department of Visual Arts Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Editor: SU Language Centre Design: Keith Dietrich Printing: Sunprint ISBN: 978-0-7972-1335-7 2 Given that the convention of an inaugural lecture Artists’ books lie at the intersection of disciplines in excludes art practice, I decided to present an inaugural ex- both the visual arts and literature, and include poetry, prose, hibition.