THE C01TTRIBUTI0TT of MARK TWAIN to MODERN RELIGIOUS THOUGHT . -By Eltse Christensen Submitted to the Faoulty Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

APRIL GIFTS 2011 Compiled By: Susan F

APRIL GIFTS 2011 Compiled by: Susan F. Glassmeyer Cincinnati, Ohio, 2011 LittlePocketPoetry.Org APRIL GIFTS 2011 1 How Zen Ruins Poets Chase Twitchel 2 Words Can Describe Tim Nolan 3 Adjectives of Order Alexandra Teague 4 Old Men Playing Basketball B.H. Fairchild 5 Healing The Mare Linda McCarriston 6 Practicing To Walk Like A Heron Jack Ridl 7 Sanctuary Jean Valentine 8 To An Athlete Dying Young A.E. Housman 9 The Routine After Forty Jacqueline Berger 10 The Sad Truth About Rilke’s Poems Nick Lantz 11 Wall Christine Garren 12 The Heart Broken Open Ronald Pies, M.D. 13 Survey Ada Jill Schneider 14 The Bear On Main Street Dan Gerber 15 Pray For Peace Ellen Bass 16 April Saturday, 1960 David Huddle 17 For My Father Who Fears I’m Going To Hell Cindy May Murphy 18 Night Journey Theodore Roethke 19 Love Poem With Trash Compactor Andrea Cohen 20 Magic Spell of Rain Ann Blandiana 21 When Lilacs Frank X. Gaspar 22 Burning Monk Shin Yu Pai 23 Mountain Stick Peter VanToorn 24 The Hatching Kate Daniels 25 To My Father’s Business Kenneth Koch 26 The Platypus Speaks Sandra Beasley 27 The Baal Shem Tov Stephen Mitchell 28 A Peasant R.S. Thomas 29 A Green Crab’s Shell Mark Doty 30 Tieh Lien Hua LiChing Chao April Gifts #1—2011 How Zen Ruins Poets I never know exactly where these annual “April Gifts” selections will take us. I start packing my bags in January by preparing an itinerary of 30 poems and mapping out a probable monthlong course. -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. -

An 'Innocent' Abroad

THE CHICAGO TRIBUNE: MONDAY. DECEMBER 24, 1877, 3 the porter about tt, and he nail the prairie was and cake stands which line either aide. On en- oysb-rs In that way—never cat them at all, In The snMl«-« confuted of old stran* nod strings It I* devoid of pleasure—very much so. The seats, TVA*TF,I>-ITIALE uut on lire at all. I now have tlicopinion that tering the auditorium, a strange sight presents fact, unless they arc smuggled into soup. on a woo !cn hw. pa>Mi><] with old carpet. The with theiriron partition". are about as uncom- fortablefor emild he. Trndee. ‘INNOCENT’ ABROAD the writer o( that hook Is an untruthful per* l,«c;ir. The gener.il effect Is that of a theatre: OS* DAT SPENT IS OAKLAND bridles were part leather and part rope. t felt, some purpose m they well AN nn',e*a \irANTr.T)-MRTAL PATrr.IWdIAKP.R. ACCHS- mildest thingI cm say of there are the stage, and actors, and was pleasure. The linn. W, C. Han- sorry They Yon cannot lie down upon them at all »V tornrd non, and that Is the audience. brimful of for the horses. seemed to feel yon happen to be without rlbe, to maklnct raitern* for malleable ;t«m But everything Is socoarse and orna- formerly comoany made anil ara esstlnx*. A<ldreM St. Louts Malleable Iron Company, him. devoid of nah, a prominent lawyer, of I.aporte. ashamed of having to appear before to yourself sp Sidney there Is a place called mentation that It gives you the impression that but now living In this looking able roll like a piece of carpel. -

National Forest Imagery Catalog Collection at the USDA

National Forest Imagery Catalog collection at the USDA - Farm Service Agency Aerial Photography Field Office (APFO) 2222 West 2300 South Salt Lake City, UT 84119-2020 (801) 844-2922 - Customer Service Section (801) 956-3653 - Fax (801) 956-3654 - TDD [email protected] http://www.apfo.usda.gov This catalog listing shows the various photographic coverages used by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and archived at the Aerial Photography Field Office. This catalog references U.S. Forest Service (FS) and other agencies imagery. For imagery prior to 1955, please contact the National Archives & Records Administration: Cartographic & Architectural Reference (NWCS-Cartographic) Aerial Photographs Team http://www.archives.gov/research/order/maps.html#contact Coverage of U.S. Forest Service photography is listed alphabetically for each forest within a region. Numeric and alpha codes used to identify FS projects are determined by the Forest Service. The original film type for most of this imagery is a natural color negative. Line indexes are available for most projects. The number of index sheets required to cover a project area is shown on the listing. Please reference the remarks column, which may identify a larger or smaller project area than the National Forest area defined in the header. Offered in the catalog listing at each National Forest heading is a link to locate the Regional and National Forest office address and phone number at: http://www.fs.fed.us/intro/directory You may wish to visit the National Forest office to view the current imagery and have them assist you in identifying aerial imagery from the APFO. -

Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1941 Mark Twain's Theories of Morality. Frank C. Flowers Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Flowers, Frank C., "Mark Twain's Theories of Morality." (1941). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 99. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/99 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MARK TWAIN*S THEORIES OF MORALITY A dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College . in. partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English By Prank C. Flowers 33. A., Louisiana College, 1930 B. A., Stanford University, 193^ M. A., Louisiana State University, 1939 19^1 LIBRARY LOUISIANA STATE UNIVERSITY COPYRIGHTED BY FRANK C. FLOWERS March, 1942 R4 196 37 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The author gratefully acknowledges his debt to Dr. Arlin Turner, under whose guidance and with whose help this investigation has been made. Thanks are due to Professors Olive and Bradsher for their helpful suggestions made during the reading of the manuscript, E. C»E* 3 7 ?. 7 ^ L r; 3 0 A. h - H ^ >" 3 ^ / (CABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT . INTRODUCTION I. Mark Twain— philosopher— appropriateness of the epithet 1 A. -

Following the Equator by Mark Twain</H1>

Following the Equator by Mark Twain Following the Equator by Mark Twain This etext was produced by David Widger FOLLOWING THE EQUATOR A JOURNEY AROUND THE WORLD BY MARK TWAIN SAMUEL L. CLEMENS HARTFORD, CONNECTICUT THE AMERICAN PUBLISHING COMPANY MDCCCXCVIII COPYRIGHT 1897 BY OLIVIA L. CLEMENS ALL RIGHTS RESERVED FORTIETH THOUSAND THIS BOOK page 1 / 720 Is affectionately inscribed to MY YOUNG FRIEND HARRY ROGERS WITH RECOGNITION OF WHAT HE IS, AND APPREHENSION OF WHAT HE MAY BECOME UNLESS HE FORM HIMSELF A LITTLE MORE CLOSELY UPON THE MODEL OF THE AUTHOR. THE PUDD'NHEAD MAXIMS. THESE WISDOMS ARE FOR THE LURING OF YOUTH TOWARD HIGH MORAL ALTITUDES. THE AUTHOR DID NOT GATHER THEM FROM PRACTICE, BUT FROM OBSERVATION. TO BE GOOD IS NOBLE; BUT TO SHOW OTHERS HOW TO BE GOOD IS NOBLER AND NO TROUBLE. CONTENTS CHAPTER I. The Party--Across America to Vancouver--On Board the Warrimo--Steamer Chairs-The Captain-Going Home under a Cloud--A Gritty Purser--The Brightest Passenger--Remedy for Bad Habits--The Doctor and the Lumbago --A Moral Pauper--Limited Smoking--Remittance-men. page 2 / 720 CHAPTER II. Change of Costume--Fish, Snake, and Boomerang Stories--Tests of Memory --A Brahmin Expert--General Grant's Memory--A Delicately Improper Tale CHAPTER III. Honolulu--Reminiscences of the Sandwich Islands--King Liholiho and His Royal Equipment--The Tabu--The Population of the Island--A Kanaka Diver --Cholera at Honolulu--Honolulu; Past and Present--The Leper Colony CHAPTER IV. Leaving Honolulu--Flying-fish--Approaching the Equator--Why the Ship Went Slow--The Front Yard of the Ship--Crossing the Equator--Horse Billiards or Shovel Board--The Waterbury Watch--Washing Decks--Ship Painters--The Great Meridian--The Loss of a Day--A Babe without a Birthday CHAPTER V. -

On State Power, Queer Aesthetics & Asian/Americanist Critique

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 6-2016 Dislocating Camps: On State Power, Queer Aesthetics & Asian/ Americanist Critique Christopher Alan Eng The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/1240 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] DISLOCATING CAMPS: ON STATE POWER, QUEER AESTHETICS & ASIAN/AMERICANIST CRITIQUE by CHRISTOPHER ALAN ENG A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2016 © 2016 CHRISTOPHER ALAN ENG All Rights Reserved ii Dislocating Camps: On State Power, Queer Aesthetics & Asian/Americanist Critique By Christopher Alan Eng This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in English in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________ ____________________________________________ Date Kandice Chuh Chair of Examining Committee _______________ ____________________________________________ Date Mario DiGangi Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Eric Lott Robert Reid-Pharr Karen Shimakawa THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT DISLOCATING CAMPS: ON STATE POWER, QUEER AESTHETICS & ASIAN/AMERICANIST CRITIQUE by Christopher Alan Eng Advisor: Kandice Chuh My dissertation argues that the history of Asian racialization in the United States requires us to grapple with the seemingly counterintuitive entanglement between “the camp” as exceptional space of biopolitical management and “camp” as a performative practice of queer excess. -

Pacific Pastoralism: Ancient Poetics & The

PACIFIC PASTORALISM: ANCIENT POETICS & THE DECONSTRUCTION OF AMERICAN PARADISE A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN AMERICAN STUDIES MAY 2014 By Travis D. Hancock Thesis Committee: Joseph Stanton (Chairperson) Brandy Nalani McDougall Robert Perkinson Keywords: Pastoral, Paradise, Pacific Islands, Hawai‘i, Herman Melville, Charles Warren Stoddard, Mark Twain, Theocritus, Longus ABSTRACT: This aim of this thesis is to deconstruct the etymology of the word “paradise” within the context of early Pacific narratives by popular American authors, and then within today’s tourist propaganda. Fundamental to that process is the imagination of “Pacific Pastoralism,” in which the pastoral tradition is considered as a predecessor to American traditions of describing the landscapes and peoples of the Pacific region, as those descriptions fueled an economy forcibly mapped onto that space. Herein texts are analyzed via close-reading comparisons, historical research, and more lyrical methods such as rhetorical stargazing, echolocation, and narrative technique. While this thesis is indebted to scholars in the fields of American Studies and English literature, it attempts to open space for Pacific Island Studies to epistemologically counter its cultural materialist claims. In total, this thesis is a critique of tourist marketing, which was ferried from antiquity to the Pacific on wooden ships, and today renders beaches little more than golf course sand-traps. Table of contents: 0. Pacific Pastoralism…………………………………………….. 1 1. Land-ho! Longus & Melville……………………………….. 14 2. Man-ho! Theocritus & Stoddard………………………….. 35 3. World-ho! Mark Twain & Literary Cartography…. -

Download Here

ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels PRAISE FOR REMEMBERING SHANGHAI “Highly enjoyable . an engaging and entertaining saga.” —Fionnuala McHugh, writer, South China Morning Post “Absolutely gorgeous—so beautifully done.” —Martin Alexander, editor in chief, the Asia Literary Review “Mesmerizing stories . magnificent language.” —Betty Peh-T’i Wei, PhD, author, Old Shanghai “The authors’ writing is masterful.” —Nicholas von Sternberg, cinematographer “Unforgettable . a unique point of view.” —Hugues Martin, writer, shanghailander.net “Absorbing—an amazing family history.” —Nelly Fung, author, Beneath the Banyan Tree “Engaging characters, richly detailed descriptions and exquisite illustrations.” —Debra Lee Baldwin, photojournalist and author “The facts are so dramatic they read like fiction.” —Heather Diamond, author, American Aloha 1968 2016 Isabel Sun Chao and Claire Chao, Hong Kong To those who preceded us . and those who will follow — Claire Chao (daughter) — Isabel Sun Chao (mother) ISABEL SUN CHAO AND CLAIRE CHAO REMEMBERING SHANGHAI A Memoir of Socialites, Scholars and Scoundrels A magnificent illustration of Nanjing Road in the 1930s, with Wing On and Sincere department stores at the left and the right of the street. Road Road ld ld SU SU d fie fie d ZH ZH a a O O ss ss U U o 1 Je Je o C C R 2 R R R r Je Je r E E u s s u E E o s s ISABEL’SISABEL’S o fie fie K K d d d d m JESSFIELD JESSFIELDPARK PARK m a a l l a a y d d y o o o o d d e R R e R R R R a a S S d d SHANGHAISHANGHAI -

1956-12 1908 Past and Future 1963

1908 — fast and future — 1963 by Edwin N orth M cClellan We look back want to 1908. over more than 48 years of OCC constructive life, and are inspired to advance. We look forward towards 1963 with sure hope and see Our Club at the ntw home tear Leahi. OCC roots, deep in Waikiki, will not be disturbed. They will spread, dig deeper and bless the New Site with structures more beautiful and uselul than erer before. The OCC must never jail in its major mission of per petuating Hawaiian aquatic sports, and serving youth, age and Hawaii. E dw in N . M cC lellan Alele Kalikimaka and Hauoli Makabiki Hou .' Every inch of the Coral Strand at Waikiki is beautiful and valuable. The New Home Site of the Outrigger Canoe Club near Castle Point about 1963, will be more desirable, attractive and valuable than the OCC site of 1908-1957. The demanding trend is towards a Perfect Beach throughout the whole Curve of Waikiki. With very splendid structures, a New Beach created and coral removed to give adequate approach to Big and Small Surfs, future OCC members will enjoy Aquatic Nature to a greater de gree than ever. The OCC may move to its New Site near Diamond Head before 1963 when present lease expires. ANCIENT ENVIRONMENT OF 1963-SITE The New Site near Diamond Head is steeped in tradition, legendary elements and history, of Old Hawaii. Gallant Ghostly Personalities fill its healthful atmosphere. So, a wee descrip tion of that environment before we view past-clubhouses of 1908, 1909, 1910, 1914, 1925-1927, 1939-1941 and other years. -

Collected Writings

THE DOCUMENTS O F TWENTIETH CENTURY ART General Editor, Jack Flam Founding Editor, Robert Motherwell Other titl es in the series available from University of California Press: Flight Out of Tillie: A Dada Diary by Hugo Ball John Elderfield Art as Art: The Selected Writings of Ad Reinhardt Barbara Rose Memo irs of a Dada Dnnnmer by Richard Huelsenbeck Hans J. Kl ein sc hmidt German Expressionism: Dowments jro111 the End of th e Wilhelmine Empire to th e Rise of National Socialis111 Rose-Carol Washton Long Matisse on Art, Revised Edition Jack Flam Pop Art: A Critical History Steven Henry Madoff Co llected Writings of Robert Mothen/le/1 Stephanie Terenzio Conversations with Cezanne Michael Doran ROBERT SMITHSON: THE COLLECTED WRITINGS EDITED BY JACK FLAM UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS Berkeley Los Angeles Londo n University of Cali fornia Press Berkeley and Los Angeles, California University of California Press, Ltd. London, England © 1996 by the Estate of Robert Smithson Introduction © 1996 by Jack Flam Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Smithson, Robert. Robert Smithson, the collected writings I edited, with an Introduction by Jack Flam. p. em.- (The documents of twentieth century art) Originally published: The writings of Robert Smithson. New York: New York University Press, 1979. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-520-20385-2 (pbk.: alk. paper) r. Art. I. Title. II. Series. N7445.2.S62A3 5 1996 700-dc20 95-34773 C IP Printed in the United States of Am erica o8 07 o6 9 8 7 6 T he paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of ANSII NISO Z39·48-1992 (R 1997) (Per111anmce of Paper) . -

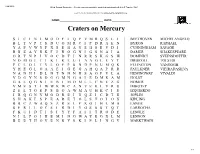

2D Mercury Crater Wordsearch V2

3/24/2019 Word Search Generator :: Create your own printable word find worksheets @ A to Z Teacher Stuff MAKE YOUR OWN WORKSHEETS ONLINE @ WWW.ATOZTEACHERSTUFF.COM NAME:_______________________________ DATE:_____________ Craters on Mercury SICINIMODFIQPVMRQSLJ BEETHOVEN MICHELANGELO BLTVPTSDUOMRCIPDRAEN BYRON RAPHAEL YAPVWYPXSEHAUEHSEVDI CUNNINGHAM SAVAGE RRZAYRKFJROGNIGSNAIA DAMER SHAKESPEARE ORTNPIVOCDTJNRRSKGSW DOMINICI SVEINSDOTTIR NOMGETIKLKEUIAAGLEYT DRISCOLL TOLSTOI PCLOLTVLOEPSNDPNUMQK ELLINGTON VANGOGH YHEGLOAAEIGEGAHQAPRR FAULKNER VIEIRADASILVA NANHIDLNTNNNHSAOFVLA HEMINGWAY VIVALDI VDGYNSDGGMNGAIEDMRAM HOLST GALQGNIEBIMOMLLCNEZG HOMER VMESTIWWKWCANVEKLVRU IMHOTEP ZELTOEPSBOAWMAUHKCIS IZQUIERDO JRQGNVMODREIUQZICDTH JOPLIN SHAKESPEARETOLSTOIOX KIPLING BBCZWAQSZRSLPKOJHLMA LANGE SFRLLOCSIRDIYGSSSTQT LARROCHA FKUIDTISIYYFAIITRODE LENGLE NILPOJHEMINGWAYEGXLM LENNON BEETHOVENRYSKIPLINGV MARKTWAIN 1/2 Mercury Craters: Famous Writers, Artists, and Composers: Location and Sizes Beethoven: Ludwig van Beethoven (1770−1827). German composer and pianist. 20.9°S, 124.2°W; Diameter = 630 km. Byron: Lord Byron (George Byron) (1788−1824). British poet and politician. 8.4°S, 33°W; Diameter = 106.6 km. Cunningham: Imogen Cunningham (1883−1976). American photographer. 30.4°N, 157.1°E; Diameter = 37 km. Damer: Anne Seymour Damer (1748−1828). English sculptor. 36.4°N, 115.8°W; Diameter = 60 km. Dominici: Maria de Dominici (1645−1703). Maltese painter, sculptor, and Carmelite nun. 1.3°N, 36.5°W; Diameter = 20 km. Driscoll: Clara Driscoll (1861−1944). American glass designer. 30.6°N, 33.6°W; Diameter = 30 km. Ellington: Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington (1899−1974). American composer, pianist, and jazz orchestra leader. 12.9°S, 26.1°E; Diameter = 216 km. Faulkner: William Faulkner (1897−1962). American writer and Nobel Prize laureate. 8.1°N, 77.0°E; Diameter = 168 km. Hemingway: Ernest Hemingway (1899−1961). American journalist, novelist, and short-story writer. 17.4°N, 3.1°W; Diameter = 126 km.