2017 Civil Society Organization Sustainability Index

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

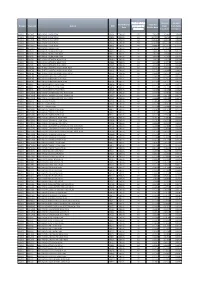

Domain Stationid Station UDC Performance Date

Number of days Amount Amount Performance Total Per Domain StationId Station UDC processed for from from Public Date Minute Rate distribution Broadcast Reception RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 NON PEAK BRA01 CENSUS 92 7.8347 4.2881 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 LOW PEAK BRB01 CENSUS 92 10.7078 7.1612 3.5466 RADIO BR ONE BBC RADIO 1 HIGH PEAK BRC01 CENSUS 92 13.5380 9.9913 3.5466 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 NON PEAK BRA02 CENSUS 92 17.4596 11.2373 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 LOW PEAK BRB02 CENSUS 92 24.9887 18.7663 6.2223 RADIO BR TWO BBC RADIO 2 HIGH PEAK BRC02 CENSUS 92 32.4053 26.1830 6.2223 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA NON PEAK BRA10 CENSUS 92 1.4814 1.4075 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA LOW PEAK BRB10 CENSUS 92 2.4245 2.3506 0.0739 RADIO BR1EXT BBC RADIO 1XTRA HIGH PEAK BRC10 CENSUS 92 3.3534 3.2795 0.0739 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK NON PEAK BRA65 CENSUS 92 1.4691 1.4593 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK LOW PEAK BRB65 CENSUS 92 2.4468 2.4371 0.0098 RADIO BRASIA BBC ASIAN NETWORK HIGH PEAK BRC65 CENSUS 92 3.4100 3.4003 0.0098 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO NON PEAK BRA62 CENSUS 92 0.1516 0.1104 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO LOW PEAK BRB62 CENSUS 92 0.2256 0.1844 0.0411 RADIO BRBEDS BBC THREE COUNTIES RADIO HIGH PEAK BRC62 CENSUS 92 0.2985 0.2573 0.0411 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE NON PEAK BRA64 CENSUS 92 0.0803 0.0569 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE LOW PEAK BRB64 CENSUS 92 0.1184 0.0951 0.0233 RADIO BRBERK BBC RADIO BERKSHIRE HIGH PEAK BRC64 CENSUS 92 0.1560 0.1327 0.0233 RADIO BRBRIS BBC -

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012

Comparative Constitutional Law SPRING 2012 PROFESSOR STEPHEN J. SCHNABLY Office: G472 http://osaka.law.miami.edu/~schnably/courses.html Tel.: 305-284-4817 E-mail: [email protected] SUPPLEMENTARY READINGS: TABLE OF CONTENTS Reference re Secession of Quebec, [1998] 2 S.C.R. 217 .................................................................1 Supreme Court Act, R.S.C., 1985, c. S-26. An Act respecting the Supreme Court of Canada................................................................................................................................11 INS v. Chadha, 462 U.S. 919 (1983) .............................................................................................12 Kenya Timeline..............................................................................................................................20 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) ..........................................................................................23 Mary L. Dudziak, Working Toward Democracy: Thurgood Marshall and the Constitution of Kenya, 56 Duke L.J. 721 (2006)....................................................................................26 Laurence Juma, Ethnic Politics and the Constitutional Review Process in Kenya, 9 Tulsa J. Comp. & Int’l L. 471 (2002) .......................................................................................34 Migai Akech, Abuse of Power and Corruption in Kenya: Will the New Constitution Enhance Government -

Stations Monitored

Stations Monitored 10/01/2019 Format Call Letters Market Station Name Adult Contemporary WHBC-FM AKRON, OH MIX 94.1 Adult Contemporary WKDD-FM AKRON, OH 98.1 WKDD Adult Contemporary WRVE-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY 99.5 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WYJB-FM ALBANY-SCHENECTADY-TROY, NY B95.5 Adult Contemporary KDRF-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 103.3 eD FM Adult Contemporary KMGA-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 99.5 MAGIC FM Adult Contemporary KPEK-FM ALBUQUERQUE, NM 100.3 THE PEAK Adult Contemporary WLEV-FM ALLENTOWN-BETHLEHEM, PA 100.7 WLEV Adult Contemporary KMVN-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MOViN 105.7 Adult Contemporary KMXS-FM ANCHORAGE, AK MIX 103.1 Adult Contemporary WOXL-FS ASHEVILLE, NC MIX 96.5 Adult Contemporary WSB-FM ATLANTA, GA B98.5 Adult Contemporary WSTR-FM ATLANTA, GA STAR 94.1 Adult Contemporary WFPG-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ LITE ROCK 96.9 Adult Contemporary WSJO-FM ATLANTIC CITY-CAPE MAY, NJ SOJO 104.9 Adult Contemporary KAMX-FM AUSTIN, TX MIX 94.7 Adult Contemporary KBPA-FM AUSTIN, TX 103.5 BOB FM Adult Contemporary KKMJ-FM AUSTIN, TX MAJIC 95.5 Adult Contemporary WLIF-FM BALTIMORE, MD TODAY'S 101.9 Adult Contemporary WQSR-FM BALTIMORE, MD 102.7 JACK FM Adult Contemporary WWMX-FM BALTIMORE, MD MIX 106.5 Adult Contemporary KRVE-FM BATON ROUGE, LA 96.1 THE RIVER Adult Contemporary WMJY-FS BILOXI-GULFPORT-PASCAGOULA, MS MAGIC 93.7 Adult Contemporary WMJJ-FM BIRMINGHAM, AL MAGIC 96 Adult Contemporary KCIX-FM BOISE, ID MIX 106 Adult Contemporary KXLT-FM BOISE, ID LITE 107.9 Adult Contemporary WMJX-FM BOSTON, MA MAGIC 106.7 Adult Contemporary WWBX-FM -

KENYA ASSESSMENT April 2000

KENYA ASSESSMENT April 2000 Country Information and Policy Unit I. SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.1 This assessment has been produced by the Country Information & Policy Unit, Immigration & Nationality Directorate, Home Office, from information obtained from a variety of sources. 1.2 The assessment has been prepared for background purposes for those involved in the asylum determination process. The information it contains is not exhaustive, nor is it intended to catalogue all human rights violations. It concentrates on the issues most commonly raised in asylum claims made in the United Kingdom. 1.3 The assessment is sourced throughout. It is intended to be used by caseworkers as a signpost to the source material, which has been made available to them. The vast majority of the source material is readily available in the public domain. 1.4 It is intended to revise the assessment on a 6-monthly basis while the country remains within the top 35 asylum producing countries in the United Kingdom. 1.5 The assessment will be placed on the Internet, http://www.homeoffice.gov.uk/ind/cipu1.htm. An electronic copy of the assessment has been made available to the following organisations: Amnesty International UK Immigration Advisory Service Immigration Appellate Authority Immigration Law Practitioners' Association Joint Council for the Welfare of Immigrants JUSTICE Medical Foundation for the care of Victims of Torture Refugee Council Refugee Legal Centre UN High Commissioner for Refugees 1 CONTENTS I SCOPE OF DOCUMENT 1.01 - 1.05 II GEOGRAPHY 2.01 - 2.02 The -

Latin America Spanish Only

Newswire.com LLC 5 Penn Plaza, 23rd Floor| New York, NY 10001 Telephone: 1 (800) 713-7278 | www.newswire.com Latin America Spanish Only Distribution to online destinations, including media and industry websites and databases, through proprietary and news agency networks (DyN and Notimex). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: • Posting to online services and portals. • Coverage on Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service, Newswire for Journalists, reaching 100,000 registered journalists from more than 170 countries and in more than 40 different languages. • Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Comprehensive newswire distribution to news media in 19 Central and South American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Domincan Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela. Translated and distributed in Spanish. Please note that this list is intended for general information purposes and may adjust from time to time without notice. 4,028 Points Country Media Point Media Type Argentina 0223.com.ar Online Argentina Acopiadores de Córdoba Online Argentina Agensur.info (Agencia de Noticias del Mercosur) Agencies Argentina AgriTotal.com Online Argentina Alfil Newspaper Argentina Amdia blog Blog Argentina ANRed (Agencia de Noticias Redacción) Agencies Argentina Argentina Ambiental -

Variable Name

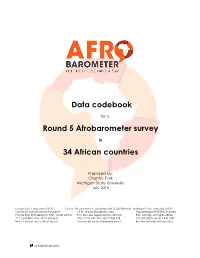

Data codebook for a Round 5 Afrobarometer survey in 34 African countries Prepared by: Chunho Park Michigan State University July 2015 University of Cape Town (UCT) Center for Democratic Development (CDD-Ghana) Michigan State University (MSU) Centre for Social Science Research 14 W. Airport Residential Area Department of Political Science Private Bag, Rondebosch, 7701, South Africa P.O. Box 404, Legon-Accra, Ghana East Lansing, Michigan 48824 27 21 650 3827•fax: 27 21 650 4657 233 21 776 142•fax: 233 21 763 028 517 353 3377•fax: 517 432 1091 Mattes ([email protected]) Gyimah-Boadi ([email protected]) Bratton ([email protected]) Copyright Afrobarometer Table of Contents Page number Variable descriptives 3-71 Appendix 1: Sample characteristics 72 Appendix 2: List of country abbreviations and country-specific codes 73 Appendix 3: Technical Information Forms for each country survey 74-107 Copyright Afrobarometer 2 Question Number: COUNTRY_ALPHA Question: Country Variable Label: Country in alphabetical order Values: 1-35 Value Labels: 1=Algeria, 2=Benin, 3=Botswana, 4=Burkina Faso, 5=Burundi, 6=Cameroon, 7=Cape Verde, 8=Cote d’Ivoire, 9=Egypt, 11=Ghana, 12=Guinea, 13=Kenya, 14=Lesotho, 15=Liberia, 16=Madagascar, 17=Malawi, 18=Mali, 19=Mauritius, 20=Morocco, 21=Mozambique, 22=Namibia, 23=Niger, 24=Nigeria, 25=Senegal, 26=Sierra Leone, 27=South Africa, 28=Sudan, 29=Swaziland, 30=Tanzania, 31=Togo, 32=Tunisia, 33=Uganda, 34=Zambia, 35=Zimbabwe Note: Answered by interviewer Question Number: RESPNO Question: Respondent number Variable Label: Respondent -

Preuzimanje Preuzimanje PDF-A

VAŠA UPUTSTVA ZA UPOTREBU Digitalno uputstvo u vozilu Proučite sadržaje uputstva za upotrebu direktno u multimedijalnom sistemu vašeg vozila (tačka menija „Vozilo“). Počnite od kratkog uputstva ili produbite svoje znanje korisnim savetima. Torbica za papire vozila Ovde možete da pronađete informacije o aktiviranju, servisna uputstva i garanciju za vaše vozilo u štampanom obliku. Digitalno uputstvo na internetu Uputstvo za upotrebu možete da pronađete na Mercedes-Benz veb-stranici. Digitalno uputstvo kao aplikacija Aplikacija Mercedes-Benz Guides je dostupna u najpoznatijim internet prodavni‐ cama aplikacija. Sprinter Uputstvo za upotrebu É9075844602Z119@ËÍ 9075844602Z119 Broj porudžbine T907 0082 19 Broj dela 907 584 46 02 Z119 Izdanje 2018-03a m Mercedes-Benz SprinterUputstvo za upotrebu Simboli Impresum U ovom uputstvu za rukovanje možete pronaći Internet sledeće simbole: Dodatne informacije o Mercedes-Benz vozilima i kompaniji Daimler AG možete da pronađete na & OPASNOST Opasnost zbog nepoštovanja internetu, na adresi: bezbednosnih napomena http://www.mercedes-benz.com Upozoravajuće napomene skreću pažnju na http://www.daimler.com opasnosti koje mogu da ugroze vaše zdravlje ili život, odnosno zdravlje ili život drugih Redakcija osoba. Pitanja i sugestije u vezi sa ovim uputstvom za upotrebu možete da pošaljete redakciji za teh‐ # Poštujte bezbednosne napomene u ničku dokumentaciju na sledeću adresu: ovom uputstvu. Daimler AG, HPC: CAC, Customer Service, 70546 Stuttgart, Deutschland + NAPOMENA ZA ZAŠTITU ŽIVOTNE SRE‐ DINE Zagađenje okoline usled nepoštova‐ ©Daimler AG: Doštampavanje, prevođenje i nja napomena za zaštitu životne sredine. umnožavanje, čak i samo delova ovog uputstva, nisu dozvoljeni bez pisane dozvole kompanije Dai‐ Napomene za zaštitu životne sredine pružaju mler AG. informacije o postupanju prema ekološkim zahtevima ili ekološkom odlaganju otpada. -

Evaluating MTV Emas 2011 with Belfast Music Week

Evaluating MTV EMAs 2011 with Belfast Music Week EVALUATING MTV EMAS 2011 WITH BELFAST MUSIC WEEK 1 The week the world came to Belfast Belfast Music Week featuring the MTV EMAs 2011 The 2011 MTV EMAs, alongside Belfast Music Week, was a landmark event for Belfast - placing the city firmly on the world musical stage. And as is only fitting for a world class event, the figures are pretty impressive: • 1.2 billion – the number of people who watched the MTV EMAs across the globe • 669 million – the number of media news opportunities generated • £22 million – the total economic impact for Belfast • £10 million – the amount of additional tourism revenue for the city • 8,000 – the number of room nights booked in Belfast hotels • 2,399 – the number of media articles released • 100% - the percentage of people who would recommend attending Belfast Music Week events • 33,500 - the number of people who attended Belfast Music Week • 170 - the number of gigs during Belfast Music Week The EMAs brought the biggest international acts to Belfast. And it wasn’t just the people of Belfast who were inspired by The ‘who’s who’ of the pop world, including Coldplay, Lady the EMAs. The world’s media arrived at our door expecting Gaga, Bruno Mars, Queen, Jessie J and Justin Bieber all the professionalism associated with such a high profile appeared at the city’s Odyssey Arena. event. Once again we did not disappoint. The enthusiasm of Belfast’s people was felt around the globe through press Meanwhile, local heroes Snow Patrol played a free open-air articles, webcasts and television broadcasts. -

Utd^L. Dean of the Graduate School Ev .•^C>V

THE FASHODA CRISIS: A SURVEY OF ANGLO-FRENCH IMPERIAL POLICY ON THE UPPER NILE QUESTION, 1882-1899 APPROVED: Graduate ttee: Majdr Prbfessor ~y /• Minor Professor lttee Member Committee Member irman of the Department/6f History J (7-ZZyUtd^L. Dean of the Graduate School eV .•^C>v Goode, James Hubbard, The Fashoda Crisis: A Survey of Anglo-French Imperial Policy on the Upper Nile Question, 1882-1899. Doctor of Philosophy (History), December, 1971, 235 pp., bibliography, 161 titles. Early and recent interpretations of imperialism and long-range expansionist policies of Britain and France during the period of so-called "new imperialism" after 1870 are examined as factors in the causes of the Fashoda Crisis of 1898-1899. British, French, and German diplomatic docu- ments, memoirs, eye-witness accounts, journals, letters, newspaper and journal articles, and secondary works form the basis of the study. Anglo-French rivalry for overseas territories is traced from the Age of Discovery to the British occupation of Egypt in 1882, the event which, more than any other, triggered the opening up of Africa by Europeans. The British intention to build a railroad and an empire from Cairo to Capetown and the French dream of drawing a line of authority from the mouth of the Congo River to Djibouti, on the Red Sea, for Tied a huge cross of European imperialism over the African continent, The point of intersection was the mud-hut village of Fashoda on the left bank of the White Nile south of Khartoum. The. Fashoda meeting, on September 19, 1898, of Captain Jean-Baptiste Marchand, representing France, and General Sir Herbert Kitchener, representing Britain and Egypt, touched off an international crisis, almost resulting in global war. -

Basisdaten 2016 1

Verzeichnis der Tabellen und Grafiken Media Perspektiven Basisdaten 2016 1 Seite Rundfunk: Programmangebot und Empfangssituation TV-Haushalte nach Empfangsebenen in Deutschland 2016 4 Empfangspotenzial der deutschen Fernsehsender 2016 4 Öffentlich-rechtlicher Rundfunk: Erträge/Leistungen Rundfunkgebühren/Rundfunkbeitrag 6 Erträge aus der Rundfunkgebühr bzw. dem Rundfunkbeitrag 7 Werbefunkumsätze der ARD-Werbung 7 Werbefernsehumsätze von ARD und ZDF 7 Programmleistung der ARD 2015: Erstes Fernsehprogramm 8 Programmleistung von ARD und ZDF für KiKA und Phoenix 2015 8 Programmleistung von ARD und ZDF für Arte 2015 9 Programmleistung des ZDF 2015 9 Programmleistung von 3sat 2015 10 Programmleistung von Deutschlandradio 2015 10 Programmleistung der Deutschen Welle 2015 11 Programmleistung der ARD 2015: Hörfunk 11 Privater Rundfunk: Erträge/Leistungen Werbeumsätze privater Hörfunkanbieter 12 Bruttowerbeumsätze privater Fernsehanbieter 12 Programmleistung von RTL 2015 13 Programmleistung von ProSieben 2015 14 Programmleistung von Sat.1 2015 14 Programmleistung von VOX 2015 14 Programmleistung von Super RTL 2015 15 Programmleistung von RTL II 2015 15 Programmleistung von kabel eins 2015 16 Programmleistung von Sport1 2015 16 Programmprofile im dualen Rundfunksystem Spartenprofile von Das Erste, ZDF, RTL, Sat.1 und ProSieben 2013 bis 2015 17 Programmstruktur 2015: Sparten und Formen von Das Erste, ZDF, RTL, Sat.1 und ProSieben 19 Themenstruktur der wichtigsten Nachrichtensendungen von ARD, ZDF, RTL und Sat.1 22 Themenkategorien und ausgewählte -

Download It From

IMD Partner in Democracy A NNUAL R EPORT 2005 The IMD – an institute of political parties for political parties The Institute for Multiparty Democracy (IMD) is an institute of political parties for political parties. Its mandate is to encourage the process of democratisation in young democracies by providing support to political parties as the core pillars of multi- party democracy. IMD works in a strictly non-partisan and inclusive manner. Through this approach, the Institute endeavours to contribute to properly functioning, sustainable pluralistic political party systems. It also supports the activities of civil society groups which play a healthy role in multi-party democracies, even though they are not part of any formal party structure. IMD was set up by seven Dutch political parties in 2000 in response to requests for support from around the world. The IMD’s founding members are the Dutch Labour Party (PvdA), Liberal Party (VVD), Christian Democratic Party (CDA), Democratic Party (D66), Green Party (GroenLinks), Christian Union (ChristenUnie) and Reformed Party (SGP). Netherlands Institute for Multiparty Democracy Korte Vijverberg 2 2513 AB The Hague The Netherlands Address per September 1, 2006: Passage 31 2511 AB The Hague The Netherlands T: +31 (0)70 311 5464 F: +31 (0)70 311 5465 E: [email protected] www.nimd.org IMD Partner in Democracy A NNUAL R EPORT 2005 Partners in Democracy Preface Without properly functioning political parties, resulted in a study for the European Parliament entitled democracies do not work well – a fact that is not yet No lasting Peace and Prosperity without Democracy & fully recognised within the international development Human Rights. -

QUARTERLY SUMMARY of RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 15Th September 2019

QUARTERLY SUMMARY OF RADIO LISTENING Survey Period Ending 15th September 2019 PART 1 - UNITED KINGDOM (INCLUDING CHANNEL ISLANDS AND ISLE OF MAN) Adults aged 15 and over: population 55,032,000 Survey Weekly Reach Average Hours Total Hours Share in Period '000 % per head per listener '000 TSA % All Radio Q 48537 88 18.0 20.4 989221 100.0 All BBC Radio Q 33451 61 8.9 14.6 488274 49.4 All BBC Radio 15-44 Q 12966 51 4.6 8.9 115944 33.9 All BBC Radio 45+ Q 20485 69 12.5 18.2 372330 57.5 All BBC Network Radio1 Q 30828 56 7.7 13.8 425563 43.0 BBC Local Radio Q 7430 14 1.1 8.4 62711 6.3 All Commercial Radio Q 35930 65 8.6 13.2 475371 48.1 All Commercial Radio 15-44 Q 17884 71 8.5 12.0 214585 62.7 All Commercial Radio 45+ Q 18046 61 8.8 14.5 260786 40.3 All National Commercial1 Q 22361 41 3.8 9.5 211324 21.4 All Local Commercial (National TSA) Q 25988 47 4.8 10.2 264047 26.7 Other Radio Q 4035 7 0.5 6.3 25577 2.6 Source: RAJAR/Ipsos MORI/RSMB 1 See note on back cover. For survey periods and other definitions please see back cover. Please note that the information contained within this quarterly data release has yet to be announced or otherwise made public Embargoed until 00.01 am and as such could constitute relevant information for the purposes of section 118 of FSMA and non-public price sensitive 24th October 2019 information for the purposes of the Criminal Justice Act 1993.