Police Under Attack: Southern California Law Enforcement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CONTACTS for LAW ENFORCEMENT STATE CONTACT INFORMATION for POLICE DEPARTMENTS NEAR WEBSTER Arizona Luke AFB 7383 N. Litchfield R

CONTACTS FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT STATE CONTACT INFORMATION FOR POLICE DEPARTMENTS NEAR WEBSTER Arizona Luke AFB City of Sunrise Police Department Luke AFB 14250 W. Statler Plaza #103 7383 N. Litchfield Road Surprise, AZ Luke AFB, AZ 85309 Ph: 623-222-4000 Arkansas Fayetteville Fayetteville Police Department 100 W Rock St Ste A Fayetteville Fayetteville, AR 72701 688 E Millsap Rd Ste 200 Ph: 479-718-7600 Fayetteville, AR 72703-3929 Fort Smith Fort Smith Police Department Fort Smith 100 S 10th St 801 Carnall Ave Ste 200 Fort Smith, AR 72901 Fort Smith, AR 72901-3758 Ph: 479-785-4221 Little Rock Little Rock Little Rock Police Department 200 W Capitol Ave Ste 1500 700 W Markham St Little Rock, AR 72201-3611 Little Rock, AR 72201 Ph: 501-371-4621 California Edwards AFB California City Police Department Edwards AFB 21130 Hacienda Blvd. 140 Methusa Ave. California, City CA 93505 Edwards AFB, CA 93524 Ph: 760-373-8606 Irvine Irvine 32 Discovery Ste 250 Irvine Police Department Irvine, CA 92618-3157 1 Civic Center Plaza Irvine, CA 92606 Los Angeles AFB, CA Ph: 949-724-7000 483 N. Aviation Blvd Bldg. 272 Los Angeles AFB, CA Los Angeles AFB, CA 90245 Los Angeles Police Department 100 W. 1st St. San Diego Los Angeles, CA 90012 6333 Greenwich Dr Ph: 213-486-1000 Ste 240 San Diego, CA 92122-5900 San Diego San Diego Police Department 9225 Aero Dr. San Diego, CA 92123 Ph: 895-495-7900 Colorado Colorado Springs Colorado Springs Police Department Colorado Springs 7850 Goddard St 5475 Tech Center Dr Ste 110 Colorado Springs, CO 80920-3981 Colorado Springs, CO 80919-2336 Ph: 719-444-3140 STATE CONTACT INFORMATION FOR POLICE DEPARTMENTS NEAR WEBSTER Greenwood Village Greenwood Village Greenwood Village Police Dept. -

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale

Equitable Sharing Payments of Cash and Sale Proceeds by Recipient Agency for California Fiscal Year 2017 Agency Name Agency Type Cash Value Sales Proceeds Totals Alameda County District Attorney's Office Local $0 $2,772 $2,772 Alameda County Narcotics Task Force Task Force $0 $13,204 $13,204 Anaheim Police Department Local $8,873 $0 $8,873 Arcadia Police Department Local $3,155 $0 $3,155 Azusa Police Department Local $542,045 $0 $542,045 Bakersfield Police Department Local $16,102 $0 $16,102 Bell Gardens Police Department Local $10,739 $0 $10,739 Berkeley Police Department Local $1,460 $59,541 $61,001 Burbank - Glendale - Pasadena Airport Authority Police Local $0 $488 $488 Butte Inter-Agency Narcotics Task Force (BINTF) Task Force $300 $0 $300 Calexico Police Department Local $11,279 $0 $11,279 Chula Vista Police Department Local $86,150 $5,624 $91,774 Citrus Heights Police Department Local $21,444 $0 $21,444 City Of Baldwin Park Police Department Local $123,681 $419 $124,100 City Of Beverly Hills Police Department Local $199,036 $578 $199,614 City Of Brawley Police Department Local $18,115 $0 $18,115 City Of Carlsbad Police Department Local $24,524 $859 $25,383 City Of Chino Police Department Local $250,475 $9,667 $260,142 City Of Coronado Police Department Local $24,524 $859 $25,383 City Of Fresno Police Department Local $16,128 $10,935 $27,063 City Of Hawthorne Police Department Local $879,841 $4,765 $884,606 City Of Huntington Beach Police Department Local $9,031 $0 $9,031 City Of Murrieta Police Department Local $133,131 $0 $133,131 -

9/11 Report”), July 2, 2004, Pp

Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page i THE 9/11 COMMISSION REPORT Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page v CONTENTS List of Illustrations and Tables ix Member List xi Staff List xiii–xiv Preface xv 1. “WE HAVE SOME PLANES” 1 1.1 Inside the Four Flights 1 1.2 Improvising a Homeland Defense 14 1.3 National Crisis Management 35 2. THE FOUNDATION OF THE NEW TERRORISM 47 2.1 A Declaration of War 47 2.2 Bin Ladin’s Appeal in the Islamic World 48 2.3 The Rise of Bin Ladin and al Qaeda (1988–1992) 55 2.4 Building an Organization, Declaring War on the United States (1992–1996) 59 2.5 Al Qaeda’s Renewal in Afghanistan (1996–1998) 63 3. COUNTERTERRORISM EVOLVES 71 3.1 From the Old Terrorism to the New: The First World Trade Center Bombing 71 3.2 Adaptation—and Nonadaptation— ...in the Law Enforcement Community 73 3.3 . and in the Federal Aviation Administration 82 3.4 . and in the Intelligence Community 86 v Final FM.1pp 7/17/04 5:25 PM Page vi 3.5 . and in the State Department and the Defense Department 93 3.6 . and in the White House 98 3.7 . and in the Congress 102 4. RESPONSES TO AL QAEDA’S INITIAL ASSAULTS 108 4.1 Before the Bombings in Kenya and Tanzania 108 4.2 Crisis:August 1998 115 4.3 Diplomacy 121 4.4 Covert Action 126 4.5 Searching for Fresh Options 134 5. -

Employment Data for California Law Enforcement 1991/92

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. EMPLOYMENT DATA FOR CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT 1991/92 - 1992/93 145590 U.S. Department of Justice National Institute of Justice This document has been reproduced exactly as received from the p~rson or organization originating It. Points of view or opinions stated in this do.c~ment ~~e those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the offiCial position or pOlicies of the National Institute of Justice. Permission to reproduce this copyrighted material has been granted by California Commission on Peace Officer Standards & Training to the National Criminal Justice Reference Service (NCJRS). Further rep~duction outside of the NCJRS system requires permission of the copyrrght owner . • • EMPLOYMENT DATA FOR 0, CALIFORNIA LAW ENFORCEMENT 1991/92 - 1992/93 • State of California Department of Justice Commission on Peace Officer Standards and Training Information Services Bureau 1601 Alhambra Boulevard Sacramento, CA 95816-7083 @ Copyrighl 1993. California Commission on '. Peace 0fIi= Standards and Training .---------- Commission on Peace OMcer Standards and Training ---------........ • COMMISSIONERS Sherman Block Sheriff ., Chairman Los Angeles County Marcel L. Leduc Sergeant Vice-Chairman San Joaquin Co. Sheriffs Department Colleue Campbell Public Member Jody Hall-Esser Chief Administrative Officer City of Culver City Edward Hunt District Attorney Fresno County Ronald Lowenberg Chief of Police Huntington Beach Daniel E. Lungren Attorney General • Ex-Officio Member Raquel Montenegro Professor of Education C.S.U.LA. Manuel Ortega Chief of Police Placentia Police Dept. Bernard C. Parks Assistant Chief Los Angeles Police Dept. Devallis Rutledge Deputy District Attorney Orange County D. -

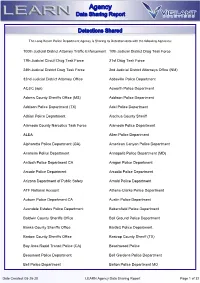

Agency Data Sharing Report

Agency Data Sharing Report Detections Shared The Long Beach Police Department Agency is Sharing its Detection data with the following Agencies: 100th Judicial District Attorney Traffic Enforcement 10th Judicial District Drug Task Force 17th Judicial Circuit Drug Task Force 21st Drug Task Force 24th Judicial District Drug Task Force 2nd Judicial District Attorneys Office (NM) 32nd Judicial District Attorney Office Abbeville Police Department ACJIC (api) Acworth Police Department Adams County Sheriffs Office (MS) Addison Police Department Addison Police Department (TX) Adel Police Department Adrian Police Department Alachua County Sheriff Alameda County Narcotics Task Force Alameda Police Department ALEA Allen Police Department Alpharetta Police Department (GA) American Canyon Police Department Anaheim Police Department Annapolis Police Department (MD) Antioch Police Department CA Aragon Police Department Arcade Police Department Arcadia Police Department Arizona Department of Public Safety Arnold Police Department ATF National Account Athens-Clarke Police Department Auburn Police Department CA Austin Police Department Avondale Estates Police Department Bakersfield Police Department Baldwin County Sheriffs Office Ball Ground Police Department Banks County Sheriffs Office Bartlett Police Department Bartow County Sheriffs Office Bastrop County Sheriff (TX) Bay Area Rapid Transit Police (CA) Beachwood Police Beaumont Police Department Bell Gardens Police Department Bell Police Department Belton Police Department MO Date Created: 08-25-20 LEARN -

"Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 5-2010 "Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers." James L. Wright UTK, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Wright, James L., ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers.". " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 2010. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/760 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. Wright entitled ""Rapping About Authenticity": Exploring the Differences in Perceptions of "Authenticity" in Rap Music by Consumers."." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Sociology. Suzaanne B. Kurth, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: Robert Emmet Jones; Hoan Bui; Debora Baldwin Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by James L. -

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry

New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel B.S. Physics Hobart and William Smith Colleges, 2004 SUBMITTED TO THE DEPARTMENT OF COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN COMPARATIVE MEDIA STUDIES AT THE MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JUNE 2008 © 2008 Evan Landon Wendel. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Signature of Author: _______________________________________________________ Program in Comparative Media Studies May 9, 2008 Certified By: _____________________________________________________________ William Uricchio Professor of Comparative Media Studies Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Accepted By: _____________________________________________________________ Henry Jenkins Peter de Florez Professor of Humanities Professor of Comparative Media Studies and Literature Co-Director, Comparative Media Studies 2 3 New Potentials for “Independent” Music Social Networks, Old and New, and the Ongoing Struggles to Reshape the Music Industry by Evan Landon Wendel Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 9, 2008 in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract This thesis explores the evolving nature of independent music practices in the context of offline and online social networks. The pivotal role of social networks in the cultural production of music is first examined by treating an independent record label of the post- punk era as an offline social network. -

At Least 17 Die in Hijack in Pakistan

. to MANCHESTER HERALD, Friday. Sept. 5. mw OPINION |T M SALES SPORTS WEEKEND PI I S TAB SALES GARS ICAMfERS/ FOR SALE TRARiRS Voters prudent, Tog sole-everythlng must BUSINESS & SERVICE DIRECTORY Bosox Increase ool Moving out of the There’s Just one Giant tog sole - G «n«ral 1979 Olds Delta "88" country, Saturday and Building Supply Com- Royole. Very good condi sewer suit shows Sundoy September 4th oony, JOO Tolland Street R S n P A M TM B / MSCElLANEBUt tion. 82500. Coll 647-9330. lead on Toronto and 7th. 158 South Moln GMLBCABE l O ^ f ------------ 1972 Shasta Trailer. 14' 1 Adelma Simmons Eost Hortford, 289-3474 (ot Street PAPEimiB 8ERVICE8 self contained. Excellent ... editorial, page 6 the Dovls ond Bradford 1948 Mecury convertlb- le,automotlc transmlssl- condition. Asking 8950 568- ... pago<i » 'VS?'’ ® General Child core In my licensed Name your own price — 4653. ... magazine Inalda Building Supply Com home. Coll 449-3015. Delivering deem form Art's tight Trucklng- on.good running Fother and son. East, loom; 5vards875phMteM. egiiars,attfcs,gorages condition,new top,l pany) September 4 thro dependable service. September 14. Anderson Also sand, stone, and cleaned.■ Juhk houi..i m - owner. Coll evenings 646- CLEAMNB Eolntlng^ Eaperhanglno grovel. Call 4434S04. .Piirnffure (indoppitaness 6299. MOTORCYCLES/ windosw, doors, kitchen 8> Removal. Coll 8724237. cabinets, roofing, hord- Large Yard sole Saturday 8ERVICE8 moved. Odd lobs, very MOPEOS September 4th,9-4pm,742 honest dependable 1978 gos VW Rabbit, stand wore, hardwoods, oak, John Deerr painting con redwood, sidings and West Middle worker. 2S^eors expe ord transmission, sun 1981 Yamaha 550 Moxlm- Tpke,Monchester. -

Anaheim Police Department 425 S

FINGERPRINTING SERVICES AGENCY DAYS HOURS FEES OTHER Anaheim Police Department 425 S. Harbor Blvd $12.00 By Appointment Only Live Scan – by appointment only Anaheim, CA 92805-3773 Cash or money order (714) 765-1997 Buena Park Police Department 15.00 (Resident) 6650 Beach Blvd Mon – Fri 9:00 am – 4:00 pm 20.00 (Non-Resident) Live Scan – by appointment only Buena Park, CA 90621-2985 Sat/Sun Cash or personal check (714) 562-3901 Costa Mesa Police Department 99 Fair Drive $10.00 Mon – Fri 8:00 am – 3:00 pm Live Scan – by appointment only Costa Mesa, CA 92626-6520 Cash or personal check (714) 754-5033 Fullerton Police Department $20.00 237 W. Commonwealth Avenue Mon – Fri By appointment only Cash, personnel check, master card Live Scan – by appointment only Fullerton, CA 92832-1810 or visa (714) 738-6800 Garden Grove Police Department 11301 Acacia Parkway $20.00 Mon – Fri 8:00 am – 6:00 pm Live Scan – by appointment only Garden Grove, CA 92840-5310 Cash or personal check (714) 741-5953 Irvine Police Department 1 Civic Center Plaza $10.00 Tue – Sat 9:00 am – 1:00 pm Live Scan – by appointment only Irvine, CA 92606-5207 Cash or personal check (949) 724-7000 La Habra Police Department 150 N. Euclid Street $26.00 Wednesday 6:00 pm – 8:00 pm Live Scan – by appointment only La Habra, CA 90631-4615 Cash or personal check (562) 905-9750 Long Beach Police Department $12.00 400 West Broadway Tue – Fri 7:45 am – 3: 45 pm Cash, personal check or Live Scan – by appointment only Long Beach, CA 90802-4401 money order (562) 570-5142 1 Revised: 9/17/13 FINGERPRINTING SERVICES AGENCY DAYS HOURS FEES OTHER Placentia Police Department $20.00 401 E Chapman Avenue Mon – Fri 8:00 am – 5:00 pm Cash, personal check or No appointment necessary Placentia, CA 92870-6101 money order (714) 993-8164 National Background Security Services, Inc. -

Applicant Rankings by State

Applicant Rankings by State *For additional information on the creation of these indices please see www.cops.usdoj.gov/Default.asp?Item=2208 **Note that this list contains 7,202 agencies. There were 58 agencies that were found to be ineligible for funding and 12 that withdrew after submitting applications, for a total of 7,272 applications received. Crime and Crime and Fiscal Need Community Final Index: Community Index: 0-50 Policing Index: 0- 0-100 Fiscal Need Policing Possible 50 Possible Possible Index Index Final Index State ORI Agency Name Points Points Points Percentile Percentile Percentile Akiachak Native Community Police AK AK002ZZ Department 31.20 36.75 67.95 99.9% 91.6% 99.9% AK AK085ZZ Tuluksak Native Community 21.18 39.44 60.62 98.5% 95.6% 99.2% AK AK038ZZ Akiak Native Community 18.85 38.40 57.25 96.7% 94.5% 98.0% AK AK033ZZ Manokotak, Village of 20.66 35.68 56.35 98.3% 89.4% 97.5% AK AK065ZZ Anvik Tribal Council 20.53 34.91 55.44 98.2% 87.6% 97.0% AK AK090ZZ Native Village of Kotlik 11.10 43.90 54.99 52.1% 98.9% 96.6% AK AK062ZZ Atmautluak Traditional Council 21.26 33.06 54.31 98.6% 82.7% 96.0% AK AK008ZZ Kwethluk, Organized Village of 25.85 25.97 51.82 99.7% 56.9% 93.8% AK AK057ZZ Gambell Police Department 20.37 30.93 51.30 98.1% 76.2% 93.0% AK AK095ZZ Alakanuk Tribal Council 22.18 26.44 48.61 99.0% 58.8% 89.4% AK AK00109 Sitka, City and Borough of 10.48 37.16 47.64 44.1% 92.3% 87.5% AK AK00102 Fairbank Department of Public Safety 11.64 35.25 46.89 58.8% 88.5% 85.8% AK AK00115 Yakutat Department of Public Safety 8.16 38.39 46.56 15.2% 94.5% 85.1% AK AK00101 Anchorage Police Department 13.52 31.27 44.79 77.3% 77.2% 80.7% AK AK00107 Petersburg Police Department 9.70 32.48 42.18 32.8% 81.3% 73.4% AK AK123ZZ Native Village of Napakiak 14.49 25.32 39.81 84.1% 54.2% 66.1% AK AK119ZZ City of Mekoryuk 12.65 26.94 39.59 69.7% 61.0% 65.4% Klawock Department of Public AK AK00135 Safety/Police Dept. -

Digest of Terrorist Cases

back to navigation page Vienna International Centre, PO Box 500, 1400 Vienna, Austria Tel.: (+43-1) 26060-0, Fax: (+43-1) 26060-5866, www.unodc.org Digest of Terrorist Cases United Nations publication Printed in Austria *0986635*V.09-86635—March 2010—500 UNITED NATIONS OFFICE ON DRUGS AND CRIME Vienna Digest of Terrorist Cases UNITED NATIONS New York, 2010 This publication is dedicated to victims of terrorist acts worldwide © United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, January 2010. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has not been formally edited. Publishing production: UNOV/DM/CMS/EPLS/Electronic Publishing Unit. “Terrorists may exploit vulnerabilities and grievances to breed extremism at the local level, but they can quickly connect with others at the international level. Similarly, the struggle against terrorism requires us to share experiences and best practices at the global level.” “The UN system has a vital contribution to make in all the relevant areas— from promoting the rule of law and effective criminal justice systems to ensuring countries have the means to counter the financing of terrorism; from strengthening capacity to prevent nuclear, biological, chemical, or radiological materials from falling into the -

University of California, Irvine, Police Department Scrapbooks AS.196

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8639w85 No online items Guide to the University of California, Irvine, Police Department scrapbooks AS.196 Finding aid prepared by Elvia Arroyo-Ramirez, 2018. Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries (cc) 2018 The UCI Libraries P.O. Box 19557 University of California, Irvine Irvine 92623-9557 [email protected] URL: http://special.lib.uci.edu Guide to the University of AS.196 1 California, Irvine, Police Department scrapbooks AS.196 Contributing Institution: Special Collections and Archives, University of California, Irvine Libraries Title: University of California, Irvine, Police Department scrapbooks Creator: University of California, Irvine. Police Department Identifier/Call Number: AS.196 Physical Description: 1.5 Linear Feet(3 document boxes) Date (inclusive): 1992-2004 Abstract: The University of California, Irvine Police Department (UCIPD) scrapbooks include collected newspaper articles, clippings, and photographs about the department from 1992-2004. Other materials include a folder about the University of California Police Department (UCPD) history, early maps of UC Irvine's campus, and one plaque awarded to the UCIPD CSO Program by the California College & University Police Chiefs Association in 2002. Language of Material: English . Access The collection is open for research. Publication Rights Property rights reside with the University of California. Copyrights are generally retained by the creators of the records and their heirs. It is the responsibility of the researcher to determine who holds the copyright and pursue the copyright owner or his or her heir for permission to publish where the UC Regents do not hold the copyright. For information on use, copyright, and attribution, please visit: http://special.lib.uci.edu/using/publishing.html Preferred Citation University of California, Irvine Police Department scrapbooks.