Feigning Or Feeling? on the Staging of Authenticity on Stage 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13Th FLOOR ELEVATORS

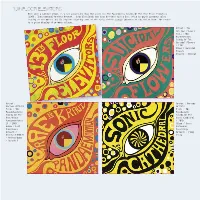

13th FLOOR ELEVATORS With such a seminal album, it’s not surprising that the cover for The Psychedelic Sounds Of The 13th Floor Elevators (1966 : International Artists Artwork : John Cleveland) has been borrowed such a lot, often by psych upstarts (also leaning on the music) and CD compliers wanting some of the early sixties garage ambience to rub off on them. The result is a great display of primary colours. Artist : The Suicidal Flowers Title : The Psychedevilic Sounds Of The Suicidal Flowers / 1997 Album / Suicidal Flowers Artwork : Unknown Artist : Artist : Various Various Artists Artists Title : The Title : The Pseudoteutonic Psychedelic Sounds Of The Sounds Of The Prae-Kraut Sonic Cathedral Pandaemonium # / 2010 14 / 2003 Album / Sonic Album / Lost Cathedral Continence Recordings Artwork / Artwork : Jimmy Reinhard Gehlen Young - Andrea Duwa - Splash 1 COVERED! PAGE 6 1 LEONA ANDERSON ASH RA TEMPEL Leona Anderson’s 1958 long-player Music To Suffer By (Unique Records) This copy of Ash Ra Tempel’s 1973 album is a gem, though I must admit I’ve never been able to get vinyl albums Starring Rosi lovingly recreates Peter to shatter quite like that (or the Buzzcocks TV show intro). The Makers Geitner’s original (cover photo : Claus have actually copied the original image for their EP and then just Kranz). added a new label design. Artist : Magic Aum Gigi Title : Starring Keiko/ 2000? Album / Fractal Records Artwork : Peter Artist : The Geitner (Photo : Makers Magic Aum Gigi) Title : Music To Suffer By / 1995 3 track EP / Estrus Wreckers Artwork : Art Chantry Artist : Smiff-N- Artist : Pavement Wessum Title : Watery, Title : Dah Shinin’ Domestic / 1992 / 1995 EP / Matador Album / Wreck Records Records Artwork : Unknown Artwork : C.M.O.N. -

Arguelles Climbs to Victory In2.70 'Mech Everest'

MIT's The Weather Oldest and Largest Today: Cloudy, 62°F (17°C) Tonight: Cloudy, misty, 52°F (11°C) Newspaper Tomorrow: Scattered rain, 63°F (17°C) Details, Page 2 Volume 119, Number 25 Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 Friday, May 7, 1999 Arguelles Climbs to Victory In 2.70 'Mech Everest' Contest By Karen E. Robinson and lubricant. will travel to Japan next year to ,SS!)( '1.1fr: .vOl'S UHI! JR The ramps were divided into compete in an international design After six rounds of competition, three segments at IS, 30, and 4S competition. Two additional stu- D~vid Arguelles '01 beat out over degree inclines with a hole at the dents who will later be selected will 130 students to become the champi- end of each incline. Robots scored compete as well. on of "Mech Everest," this year's points by dropping the pucks into 2.;0 Design Competition. these holes and scored more points Last-minute addition brings victory The contest is the culmination of for pucks dropped into higher holes. Each robot could carry up to ten the Des ign and Engineering 1 The course was designed by Roger pucks to drop in the holes. Students (2,.007) taught by Professor S. Cortesi '99, a student of Slocum. could request an additional ten Alexander H. Slocum '82. Some robots used suction to pucks which could not be carried in Kurtis G. McKenney '01, who keep their treads from slipping the robot body. Arguelles put these finished in second place, and third down the table, some clung to the in a light wire contraption pulled by p\~ce finisher Christopher K. -

Scott Myrick Overview Resume

DANCE Feature Films: Award Shows: Katy Perry: Part Of Me 2010 VMAs - Opening Number Jack and Jill 2010 AMAs - Katy Perry “Firework” La La Land 2011 Grammys - KP “Teenage Dream” Birds Of Prey - Harley Quinn 2012 Grammys - KP “Part Of Me” 2012 VMAs - Taylor Swift “WANEGBT” 2012 AMAs - Taylor Swift “IKYWT” Tour: 2013 Grammys - TS “WANEGBT” Katy Perry California Dreams Tour 2013 Brit Awards - TS “IKYWT” Taylor Swift Red Tour 2013 Billboard Awards - TS “22” Katy Perry Prismatic Tour 2013 MTV VMAs - KP “Roar” Demi Lovato Tell Me You Love Me Tour 2013 AMAs - KP “Unconditionally” 2013 NRJ Awards - KP “Unconditionally” 2014 Grammys - KP “Dark Horse" Television: 2017 Grammys - KP “CTTR” Jerry Lewis Telethon 2017 MTV Movie Awards - Opening DWTS Jason Derulo House - Bombshells Glee - Saturday Night Fever Music Videos: VH1 Divas Taylor Swift - 22 DWTS Selena Gomez Taylor Swift - Red Disney’s Shake It Up Katy Perry - This Is How We Do Glee - Starships & Pinball Wizard X Factor DWTS “Heavy Metal Lover” Stage: Gilmore Girls - Netflix Rock In Rio Brazil - Katy Perry Greatest Hits - Coolio Obama Presidential Campaign Katy Perry Super Bowl Halftime Show Jessie & The ToyBoys - Jingle Ball SNL - Katy Perry Capital FM Ball - Taylor Swift & KP The Voice - Berlin iTunes Festival - Katy Perry DWTS Season 24 Finale iHeart Radio - Katy Perry Lip Sync Battle - Season 3-5 Rock in Rio Brazil - Katy Perry Prismatic CMA Country Christmas MET Opera “The Merry Widow” Curb Your Enthusiasm - “Fatwa” Swansea Festival - Demi Lovato Nickelodeon - “Its On” Rock In Rio Lisbon -

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural Risk At

University of Southern Queensland Behavioural risk at outdoor music festivals Aldo Salvatore Raineri Doctoral Thesis Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Professional Studies at the University of Southern Queensland Volume I April 2015 Supervisor: Prof Glen Postle ii Certification of Dissertation I certify that the ideas, experimental work, results, analyses and conclusions reported in this dissertation are entirely my own effort, except where otherwise acknowledged. I also certify that the work is original and has not been previously submitted for any other award, except where otherwise acknowledged. …………………………………………………. ………………….. Signature of candidate Date Endorsement ………………………………………………….. …………………… Signature of Supervisor Date iii Acknowledgements “One’s destination is never a place, but a new way of seeing things.” Henry Miller (1891 – 1980) An outcome such as this dissertation is never the sole result of individual endeavour, but is rather accomplished through the cumulative influences of many experiences and colleagues, acquaintances and individuals who pass through our lives. While these are too numerous to list (or even remember for that matter) in this instance, I would nonetheless like to acknowledge and thank everyone who has traversed my life path over the years, for without them I would not be who I am today. There are, however, a number of people who deserve singling out for special mention. Firstly I would like to thank Dr Malcolm Cathcart. It was Malcolm who suggested I embark on doctoral study and introduced me to the Professional Studies Program at the University of Southern Queensland. It was also Malcolm’s encouragement that “sold” me on my ability to undertake doctoral work. -

Christian Rock Concerts As a Meeting Between Religion and Popular Culture

ANDREAS HAGER Christian Rock Concerts as a Meeting between Religion and Popular Culture Introduction Different forms of artistic expression play a vital role in religious practices of the most diverse traditions. One very important such expression is music. This paper deals with a contemporary form of religious music, Christian rock. Rock or popular music has been used within Christianity as a means for evangelization and worship since the end of the 1960s.1 The genre of "contemporary Christian music", or Christian rock, stands by definition with one foot in established institutional (in practicality often evangelical) Christianity, and the other in the commercial rock music industry. The subject of this paper is to study how this intermediate position is manifested and negotiated in Christian rock concerts. Such a performance of Christian rock music is here assumed to be both a rock concert and a religious service. The paper will examine how this duality is expressed in practices at Christian rock concerts. The research context of the study is, on the one hand, the sociology of religion, and on the other, the small but growing field of the study of religion and popular culture. The sociology of religion discusses the role and posi- tion of religion in contemporary society and culture. The duality of Chris- tian rock and Christian rock concerts, being part of both a traditional religion and a modern medium and business, is understood here as a concrete exam- ple of the relation of religion to modern society. The study of the relations between religion and popular culture seems to have been a latent field within research on religion at least since the 1970s, when the possibility of the research topic was suggested in a pioneer volume by John Nelson (1976). -

80,000,000 Hooligans. Discourses of Resistance to Racism and Xenophobia in German Punk Lyrics 19911994

80,000,000 hooligans. Discourses of resistance to racism and xenophobia in German punk lyrics 1991-1994 Article Accepted Version Schröter, M. (2015) 80,000,000 hooligans. Discourses of resistance to racism and xenophobia in German punk lyrics 1991-1994. Critical Discourse Studies, 12 (4). pp. 398-425. ISSN 1740-5904 doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2014.1002508 Available at http://centaur.reading.ac.uk/38658/ It is advisable to refer to the publisher’s version if you intend to cite from the work. See Guidance on citing . To link to this article DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2014.1002508 Publisher: Taylor & Francis All outputs in CentAUR are protected by Intellectual Property Rights law, including copyright law. Copyright and IPR is retained by the creators or other copyright holders. Terms and conditions for use of this material are defined in the End User Agreement . www.reading.ac.uk/centaur CentAUR Central Archive at the University of Reading Reading’s research outputs online 80.000.000 Hooligansi. Discourse of Resistance to Racism and Xenophobia in German Punk Lyrics 1991-1994 Melani Schröter Department of Modern Languages and European Studies, University of Reading, Whiteknights PO Box 218, Reading RG6 6AA, [email protected] The late eighties and early nineties in Germany were not only marked by the fall of the Wall and German unification, but also by the dramatization of the political issue of asylum, resulting in outbreaks of xenophobic violence. In the context of the asylum debate of the early nineties, a number of punk bands produced songs between 1991 and 1994 which criticise the xenophobic climate created by the asylum debate and undermine an exculpatory official discourse about the violent attacks. -

YDC Talks to Adam Goldstein of SPLC Kathy Zhang Adam Goldstein Answers a Physical Disruption of the School Day

In this issue Annual Reader Survey 4 Entertainment 9–10 Humor 13 Lifestyle 5–7 C-SPAN airs YDC previews On the Street 16 key equal News 1–3, 15 summer movies Sports 12 rights cases p. 8 Viewpoints 14 p. 5 Volume 20 • Number 4 • Summer 2011 Please display through Labor Day YDC talks to Adam Goldstein of SPLC Kathy Zhang Adam Goldstein answers a physical disruption of the school day. They cer- questions from college and Young D.C. high school students in the tainly don’t have a general right to police what Censorship is the outcome of schools maintain- Ask Adam feature at www. students do at home, even if they do it online, and splc.org. ing order by reducing the free speech of students. Readers can view the even if school computers can access the speech. Adam Goldstein, attorney advocate for the Student censored stick figure The fact that online speech may eventually find its cartoon of the Ithaca case Press Law Center (SPLC), told YDC why censorship by visiting http://www. way on campus doesn’t mean that student speak- is not the best way to go and does not even work. splc.org/news/newsflash. ers are always on campus when they’re online. asp?id=2222 then scrolling In 2008,when students at Ithaca HS in New to and clicking on “view the YDC: As student-run blogs and [independent] York were not allowed to print a cartoon in the cartoon.” newspapers are not reviewed, if a student pub- school newspaper, they created an independent pub- Screenshot from Ask Adam video lishes false information about another student or a lication called The March Issue and printed the car- nors as they grow up. -

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle

Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle by Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis A dissertation submitted to the Department of American Literature and Culture, School of English in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Philosophy Aristotle University of Thessaloniki Konstantinos Chatzipapatheodoridis Strut, Sing, Slay: Diva Camp Praxis and Queer Audiences in the Arena Tour Spectacle Supervising Committee Zoe Detsi, supervisor _____________ Christina Dokou, co-adviser _____________ Konstantinos Blatanis, co-adviser _____________ This doctoral dissertation has been conducted on a SSF (IKY) scholarship via the “Postgraduate Studies Funding Program” Act which draws from the EP “Human Resources Development, Education and Lifelong Learning” 2014-2020, co-financed by European Social Fund (ESF) and the Greek State. Aristotle University of Thessaloniki I dress to kill, but tastefully. —Freddie Mercury Table of Contents Acknowledgements...................................................................................i Introduction..............................................................................................1 The Camp of Diva: Theory and Praxis.............................................6 Queer Audiences: Global Gay Culture, the Arena Tour Spectacle, and Fandom....................................................................................24 Methodology and Chapters............................................................38 Chapter 1 Times -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

„Locker Aus Dem Bauch Raus“

Gesellschaft muss man sich auch ein bisschen ans Bein pieseln lassen können. SHOWGESCHÄFT SPIEGEL: Punk-Rock bedeutete mal, immer mit Absicht in die Abseitsfalle zu laufen. Rennen die Toten Hosen mit ihrem Anti- „Locker aus dem Bauch raus“ Bayern-Lied jetzt nicht offene Türen ein? Campino: Nein, Bayern München kommt Popstar Campino über die Anti-FC-Bayern-Hymne seiner in der Gunst des Volkes eher noch viel zu gut weg. Ich glaube, wenn wir den Islam an- Band Die Toten Hosen, Gemeinsamkeiten mit Bayern-Manager gegriffen hätten, hätten wir weniger Ärger Uli Hoeneß und die neue Tote-Hosen-CD „Unsterblich“ bekommen. Campino, 37, ist seit 1982 Sänger der Toten Hosen und noch länger Fan der Düssel- dorfer Fortuna. SPIEGEL: Campino, wie hat letztes Wochen- ende Ihr Lieblingsverein Fortuna Düssel- dorf gespielt? Campino: Keine Ahnung, ich war seit drei Wochen nicht mehr zu Hause. Und in der Zeitung taucht Fortuna nicht mehr auf, seit sie in der Regionalliga West/Südwest kickt. SPIEGEL: Ist es dann nicht besonders dreist, wie die Toten Hosen auf ihrer neuen CD über den Deutschen Meister und Tabel- lenführer Bayern München herziehen: „Was für Eltern muss man haben, um so verdorben zu sein, einen Vertrag zu unter- schreiben bei diesem Scheißverein“? Campino: Wir werden fußballmäßig sowie- M. WITT so nicht mehr für voll genommen, seitdem BONGARTS wir Repräsentanten eines Drittliga-Clubs Fußballfan Campino, Bayern-München-Stars*: „Typen, die nicht verlieren können“ sind.Aber bei der Fortuna handelt sich we- nigstens nicht um eine arrogante Truppe, Campino: Was heißt denn hier „die armen SPIEGEL: Die Erregung der Bayern-Chefs die besser spielen könnte, wenn sie nur Bayern“? Denen schließen sich doch nur hat doch sicher mitgeholfen, dass die neue wollte. -

Free Part of Me Katty

Free part of me katty click here to download Katy Perry - On Tour. i love katy so much and this song and a music video are just amazing like the rest. Get “Part Of Me” from Katy Perry's 'Teenage Dream: The Complete Confection': www.doorway.ru Thanks for watching! This song is so uplifting, I love it. Lyrics to 'Part Of Me' by Katy Perry. Days like this I want to drive away / Pack my bags and watch your shadow fade / You chewed me up and spit me out / Like I. "Part of Me" is a song by American singer Katy Perry, released as the lead single from Teenage Dream: The Complete Confection. It was written by Perry, and Bonnie McKee, with production and additional writing by Dr. Luke, Max Martin, and Cirkut. The song was not included on the original edition of Teenage Dream Composition and lyrical · Music video · Live performances · Usage in media. Katy Perry: Part of Me Katy Perry who is a pop star has a huge number of fan in the world. She is always herself why she gets great successes in her life. Watch Katy Perry: Part Of Me Online | katy perry: part of me | Katy Perry: Part Of Me () | Director. Part of Me Lyrics: Days like this, I want to drive away / Pack my bags and watch your shadow fade / You chewed me up and spit me out / Like I was poison in your mouth / You took my light, you drain. Lyrics to "Part Of Me" song by Katy Perry: Days like this I want to drive away Pack my bags and watch your shadow fade You chewed me up and sp. -

Die Toten Hosen

Die Toten Hosen Am Anfang war der Lärm Bearbeitet von Philipp Oehmke 1. Auflage 2015. Taschenbuch. 384 S. Paperback ISBN 978 3 499 63003 3 Format (B x L): 12,5 x 19 cm schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. Leseprobe aus: Philipp Oehmke Die Toten Hosen Mehr Informationen zum Buch finden Sie auf rowohlt.de. Copyright © 2015 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg DIE TOTEN HOSEN AM ANFANG WAR DER LÄRM Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag 3 DTH_Taschebuch_Kapitel.indd 2 08.10.15 11:16 DTH_Taschebuch_Kapitel.indd 3 08.10.15 11:16 Inhalt Der Anruf 7 Vorgärten 37 Schwerstarbeit 87 Düsseldorf 119 Ehemaligentreff 159 Gründerzeit 177 1000 213 Wendepunkte 243 Blaue Stunde 281 Grenzbereich 313 Endspiel 359 Veröffentlicht im Rowohlt Taschenbuch Verlag, Reinbek bei Hamburg, Dezember 2015 Copyright © 2014 by Rowohlt Verlag GmbH, Reinbek bei Hamburg Gestaltung Bildteil Dirk Rudolph Innentypografie und Herstellung Daniel Sauthoff Satz Newzald PostScript (InDesign) bei Pinkuin Satz und Datentechnik, Berlin Druck und Bindung CPI books GmbH, Leck, Germany ISBN 978 3 499 63003 3 Inhalt Der Anruf 7 Vorgärten 37 Schwerstarbeit 87 Düsseldorf 119 Ehemaligentreff 159 Gründerzeit 177 1000 213 Wendepunkte 243 Blaue Stunde 281 Grenzbereich 313 Endspiel 359 5 7 DTH_Taschebuch_Kapitel.indd 5 08.10.15 11:16 Der Anruf ANDI: Da schluckst du, klar.