Athenian Empire 478To 404B.C. Formation Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures

��������������������������������� Creating the Past: Roman Villa Sculptures Hadrian’s pool reflects his wide travels, from Egypt to Greece and Rome. Roman architects recreated old scenes, but they blended various elements and styles to create new worlds with complex links to ideal worlds. Romans didn’t want to live in the past, but they wanted to live with it. Why “creating” rather than “recreating” the past? Most Roman sculpture was based on Greek originals 100 years or more in the past, but these Roman copies, in their use & setting, created a view of the past as the Romans saw it. In towns, such as Pompeii, houses were small, with little room for large gardens (the normal place for statues), so sculpture was under life-size and highlighted. The wall frescoes at Pompeii or Boscoreale (as in the reconstructed room at the Met) show us what the buildings and the associated sculptures looked like. Villas, on the other hand, were more expansive, generally sited by the water and had statues, life-size or larger, scattered around the gardens. Pliny’s villas, as he describes them in his letters, show multiple buildings, seemingly haphazardly distributed, connected by porticoes. Three specific villas give an idea of the types the Villa of the Papyri near Herculaneum (1st c. AD), Tiberius’ villa at Sperlonga from early 1st century (described also in CHSSJ April 1988 lecture by Henry Bender), and Hadrian’s villa at Tivoli (2nd cent AD). The Villa of Papyri, small and self-contained, is still underground, its main finds having been reached by tunneling; the not very scientific excavation left much dispute about find-spots and the villa had seen upheaval from the earthquake of 69 as well as the Vesuvius eruption of 79. -

The Satrap of Western Anatolia and the Greeks

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Eyal Meyer University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Ancient History, Greek and Roman through Late Antiquity Commons Recommended Citation Meyer, Eyal, "The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2473. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2473 For more information, please contact [email protected]. The aS trap Of Western Anatolia And The Greeks Abstract This dissertation explores the extent to which Persian policies in the western satrapies originated from the provincial capitals in the Anatolian periphery rather than from the royal centers in the Persian heartland in the fifth ec ntury BC. I begin by establishing that the Persian administrative apparatus was a product of a grand reform initiated by Darius I, which was aimed at producing a more uniform and centralized administrative infrastructure. In the following chapter I show that the provincial administration was embedded with chancellors, scribes, secretaries and military personnel of royal status and that the satrapies were periodically inspected by the Persian King or his loyal agents, which allowed to central authorities to monitory the provinces. In chapter three I delineate the extent of satrapal authority, responsibility and resources, and conclude that the satraps were supplied with considerable resources which enabled to fulfill the duties of their office. After the power dynamic between the Great Persian King and his provincial governors and the nature of the office of satrap has been analyzed, I begin a diachronic scrutiny of Greco-Persian interactions in the fifth century BC. -

Demetrius Poliorcetes and the Hellenic League

DEMETRIUSPOLIORCETES AND THE HELLENIC LEAGUE (PLATE 33) 1. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND D JURING the six years, 307/6-302/1 B.C., issues were raised and settled which shaped the course of western history for a long time to come. The epoch was alike critical for Athens, Hellas, and the Macedonians. The Macedonians faced squarely during this period the decision whether their world was to be one world or an aggregate of separate kingdoms with conflicting interests, and ill-defined boundaries, preserved by a precarious balance of power and incapable of common action against uprisings of Greek and oriental subjects and the plundering appetites of surrounding barbarians. The champion of unity was King Antigonus the One- Eyed, and his chief lieutenant his brilliant but unstatesmanlike son, King Demetrius the Taker of Cities, a master of siege operations and of naval construction and tactics, more skilled in organizing the land-instruments of warfare than in using them on the battle field. The final campaign between the champions of Macedonian unity and disunity opened in 307 with the liberation of Athens by Demetrius and ended in 301 B.C. with the Battle of the Kings, when Antigonus died in a hail of javelins and Demetrius' cavalry failed to penetrate a corps of 500 Indian elephants in a vain effort to rescue hinm. Of his four adversaries King Lysimachus and King Kassander left no successors; the other two, Kings Ptolemy of Egypt and Seleucus of Syria, were more fortunate, and they and Demetrius' able son, Antigonus Gonatas, planted the three dynasties with whom the Romans dealt and whom they successively destroyed in wars spread over 44 years. -

On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras

The Classical Quarterly http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ Additional services for The Classical Quarterly: Email alerts: Click here Subscriptions: Click here Commercial reprints: Click here Terms of use : Click here On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras A. E. Taylor The Classical Quarterly / Volume 11 / Issue 02 / April 1917, pp 81 - 87 DOI: 10.1017/S0009838800013094, Published online: 11 February 2009 Link to this article: http://journals.cambridge.org/abstract_S0009838800013094 How to cite this article: A. E. Taylor (1917). On the Date of the Trial of Anaxagoras. The Classical Quarterly, 11, pp 81-87 doi:10.1017/S0009838800013094 Request Permissions : Click here Downloaded from http://journals.cambridge.org/CAQ, IP address: 128.122.253.212 on 28 Apr 2015 ON THE DATE OF THE TRIAL OF ANAXAGORAS. IT is a point of some interest to the historian of the social and intellectual development of Athens to determine, if possible, the exact dates between which the philosopher Anaxagoras made that city his home. As everyone knows, the tradition of the third and later centuries was not uniform. The dates from which the Alexandrian chronologists had to arrive at their results may be conveniently summed up under three headings, (a) date of Anaxagoras' arrival at Athens, (6) date of his prosecution and escape to Lampsacus, (c) length of his residence at Athens, (a) The received account (Diogenes Laertius ii. 7),1 was that Anaxagoras was twenty years old at the date of the invasion of Xerxes and lived to be seventy-two. This was apparently why Apollodorus (ib.) placed his birth in Olympiad 70 and his death in Ol. -

Excavating Classical Amphipolis & on the Lacedaemonian General

Adelphi University Adelphi Digital Commons Anthropology Faculty Publications Anthropology 12-1-2002 Excavating Classical Amphipolis & On the Lacedaemonian General Brasidas Chaido Koukouli-Chrysanthaki Anagnostis P. Agelarakis Adelphi University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.adelphi.edu/ant_pubs Part of the Anthropology Commons Repository Citation Koukouli-Chrysanthaki, Chaido and Agelarakis, Anagnostis P., "Excavating Classical Amphipolis & On the Lacedaemonian General Brasidas" (2002). Anthropology Faculty Publications. 12. https://digitalcommons.adelphi.edu/ant_pubs/12 This Journal Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Anthropology at Adelphi Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Anthropology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Adelphi Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 3 Excavating Classical Amphipolis Chaido Koukouli -Chrysanthaki The excavations carried out by D. Lazaridis between discovered and excavated;5 there is strong evidence 1956 and 1984 uncovered part of the ancient city of that the city's theatre was located next to it. 6 Amphipolis and its cemeteries, 1 [fig. 1] namely the external walls, the acropolis and, within the walls, In the northern part of the city were discovered: the remains of public and private buildings. On the sanctuary of Klio/ founded during the earliest years acropolis, the Early Christian basilicas destroyed the of the colony; further to the west, a small sanctuary city's important sanctuaries - those of Artemis of Attis dating to the Hellenistic and Early Roman Tauropolos,2 Athena3 and Asclepios4 - which literary periods;8 and, outside the north wall, a small sanctu sources and fragmentary votive inscriptions locate ary of a nymph. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

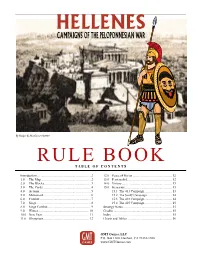

Rule Book T a B L E O F C O N T E N T S

HELLENES: Campaigns of the Peloponnesian War 1 RULE BOOK T A B L E O F C O N T E N T S Introduction .................................................................. 2 12.0 Peace of Nicias ................................................ 12 1.0 The Map ............................................................. 2 13.0 Persian Aid ....................................................... 12 2.0 The Blocks ......................................................... 3 14.0 Victory ............................................................. 13 3.0 The Cards ........................................................... 4 15.0 Scenarios .......................................................... 13 4.0 Actions ............................................................... 5 15.1 The 431 Campaign .................................. 13 5.0 Movement .......................................................... 6 15.2 The Sicily Campaign .............................. 14 6.0 Combat .............................................................. 7 15.3 The 413 Campaign .................................. 14 7.0 Siege .................................................................. 8 15.4 The 415 Campaign .................................. 15 8.0 Siege Combat ..................................................... 9 Strategy Notes ............................................................ 15 9.0 Winter .............................................................. 10 Credits ....................................................................... 15 10.0 -

Gerald Deslandes March 2018

The Religious Art of Sicily: 600 BC – 1200 AD A study day comprising three lectures by Gerald Deslandes 7 March 2018: 10.30 - 15.30 Perseus Slaying Medusa c 550 B.C. from Temple C at Selinunte Winchester Art History Group www.wahg.org.uk 1 Phoenician Libation Bowl, 8�� Century BC The traditional way of describing the early religious art of Sicily is to present it as a product of distinct political and religious cultures and as part of a wider narrative of conflict between east and west. It is true that there is evidence of a struggle between Greek and Phoenician influences from about 750 BC, which is mirrored in the rivalry of the Carthaginians and the Romans from 264 BC. After the fall of Rome in 476 the island came under the sway of the Byzantines in 728 AD and of the Arabs in 840 AD. The conversion of Byzantine churches to Islamic mosques that took place was then reversed during the Norman era from 1038 to 1194 AD. The difference was that instead of reverting to Byzantine authority, they came under the aegis of the Lateran tradition of the pope in Rome. For these reasons it is tempting to compare Count Roger’s seizure of Palermo in 1071 to the reconquest of Cordoba in 1080 or the launching of the first Crusade in 1095. Yet the political and religious identity of Europe that these struggles helped to define was still largely undetermined at the 2 end of the Norman era. In the ancient world the links between all four corners of the Mediterranean are evoked by Plato’s description of the great cultures of antiquity as grouped around it ‘like frogs around a pond’. -

Use This Knowledge Organizer to Become an Expert in Our Topic!

490 – 449 BC Wars with Persia ancient – from the distant past modern- belonging to the present or recent times Battle of Marathon: famous Greek victory in war civilisation – a society or culture at a particular time in history 490BC with the Persians. Pheidippides is said to have philosophy – a study of the nature of knowledge and existence run from Athens to Sparta to fetch help. citizens – a person belonging to a particular city or country Battle of Thermopylae: King Leoidas and the 480BC democracy – government of a country by representatives elected by all of the people Spartans were defeated by the Persians. archaeology - the study of ancient civilizations by digging for the remains of their buildings, Battle of Salamis – a sea battle in which the tools etc. 480BC Greeks defeated the Persians under King myth – a story told to explain a natural or social phenomenon Xerxes by sinking 200 ships. legend – a traditional story sometimes thought to be historical 480 BC – 280 BC Classical Greece hoplite – foot soldier victory – a success won against an enemy in battle Peloponnesian War between Athens & Sparta. cavalry – soldiers on horseback Sparta won. The threat of invasion by a foreign 431 - 404 BC archers - soldiers fighting with bows and arrows enemy made the Greeks fight together. Their main enemy was Persia. crest – a design representing a family or organization oath – a solemn promise to do something debate - a formal discussion or argument worn by women himation – cloak ostracon – a broken piece of pottery used to write the names -

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy

Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy By Daniel Christopher Walin A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Donald J. Mastronarde Professor Kathleen McCarthy Professor Emily Mackil Spring 2012 1 Abstract Slaves, Sex, and Transgression in Greek Old Comedy by Daniel Christopher Walin Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair This dissertation examines the often surprising role of the slave characters of Greek Old Comedy in sexual humor, building on work I began in my 2009 Classical Quarterly article ("An Aristophanic Slave: Peace 819–1126"). The slave characters of New and Roman comedy have long been the subject of productive scholarly interest; slave characters in Old Comedy, by contrast, have received relatively little attention (the sole extensive study being Stefanis 1980). Yet a closer look at the ancestors of the later, more familiar comic slaves offers new perspectives on Greek attitudes toward sex and social status, as well as what an Athenian audience expected from and enjoyed in Old Comedy. Moreover, my arguments about how to read several passages involving slave characters, if accepted, will have larger implications for our interpretation of individual plays. The first chapter sets the stage for the discussion of "sexually presumptive" slave characters by treating the idea of sexual relations between slaves and free women in Greek literature generally and Old Comedy in particular. I first examine the various (non-comic) treatments of this theme in Greek historiography, then its exploitation for comic effect in the fifth mimiamb of Herodas and in Machon's Chreiai. -

Athens' Domain

Athens’ Domain: The Loss of Naval Supremacy and an Empire Keegan Laycock Acknowledgements This paper has a lot to owe to the support of Dr. John Walsh. Without his encouragement, guid- ance, and urging to come on a theoretically educational trip to Greece, this paper would be vastly diminished in quality, and perhaps even in existence. I am grateful for the opportunity I have had to present it and the insight I have gained from the process. Special thanks to the editors and or- ganizers of Canta/ἄειδε for their own patience and persistence. %1 For the Athenians, the sea has been a key component of culture, economics, and especial- ly warfare. The Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC) displayed how control of the waves was vital for victory. This was not wholly apparent at the start of the conflict. The Peloponnesian League was militarily led by Sparta who was the greatest land power in Greece; to them naval warfare was excessive. Athens, as the head of the Delian League, was the greatest sea power in Greece whose strengths lay in their navy. However, through a combination of factors, Athens lost control of the sea and lost the war despite being the superior naval power at the war’s outset. Ultimately, Athens lost because they were unable to maintain strong naval authority. The geographic position of Athens and many of its key resources ensured land-based threats made them vulnerable de- spite their naval advantage. Athens also failed to exploit their naval supremacy as they focused on land-based wars in Sicily while the Peloponnesian League built up a rivaling navy of its own. -

Impact of the Plague in Ancient Greece M.A

Infect Dis Clin N Am 18 (2004) 45–51 Impact of the plague in Ancient Greece M.A. Soupios, EdD, PhD Department of Political Science, Long Island University, C.W. Post Campus, 720 North Boulevard, Brookville, NY 11548, USA The Peloponnesian War is not an isolated incident in the social and military history of ancient Greece. It is better understood as the most spectacular example of a bloody internecine instinct that plagued Hellas throughout most of its history. In the absence of the generalized threat posed by the Great King’s army, the grand alliance that successfully had repulsed the Persian juggernaut in 480 to 479 BC soon began to unravel. Spurred by Athenian adventurism, the Greeks quickly reverted to their traditional jealousies and hatreds. The expansive lusts of Athens convinced Sparta and her allies that the Athenians were a menace to Hellas’ strategic balance of power and that conflict was necessary and inevitable. Formal hostilities commenced in 431 BC and continued intermittently for the next 27 years, during which time much of the luster of the Golden Age of Greece was tarnished irreversibly. War and disease In the 5th century BC, an infantry unit known as the phalanx dominated Greek warfare. This formation was comprised of hoplites, citizen–soldiers who took their name from a large wooden shield (hoplon) that they carried into battle [1]. The killing efficiency of the phalanx had been field-tested thoroughly in the struggles against Persia. In 431 BC, the Greeks redirected their war machine toward fratricidal ends. The Spartans, with their iron discipline and ready willingness to sacrifice all, were the acknowledged masters of this infantry combat.