Geotour Guide for Terrace, BC

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

E.1 0868-006-20 KSM Gitxsan Desk-Based Research

APPENDIX 30-D GITXSAN NATION TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND USE DESK-BASED RESEARCH REPORT TM Seabridge Gold Inc. KSM PROJECT Gitxsan Nation Traditional Knowledge and Use Desk-based Research Report Rescan™ Environmental Services Ltd. Rescan Building, Sixth Floor - 1111 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6E 2J3 October 2012 Tel: (604) 689-9460 Fax: (604) 687-4277 KSM PROJECT GITXSAN NATION TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND USE DESK-BASED RESEARCH REPORT October 2012 Project #0868-006-20 Citation: Rescan. 2012. KSM Project: Gitxsan Nation Traditional Knowledge and Use Desk-based Research Report . Prepared for Seabridge Gold Inc. by Rescan Environmental Services Ltd.: Vancouver, British Columbia. Prepared for: Seabridge Gold Inc. Prepared by: Rescan™ Environmental Services Ltd. Vancouver, British Columbia KSM PROJECT GITXSAN NATION TRADITIONAL KNOWLEDGE AND USE DESK-BASED RESEARCH REPORT Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................................... i List of Figures .................................................................................................... ii List of Tables ..................................................................................................... ii Acronyms and Abbreviations ........................................................................................... iii 1. Introduction .................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Project Proponent .................................................................................. -

Inside Passage & Skeena Train

Northern Expedition Fraser River jetboat INSIDE PASSAGE & Activity Level: 2 SKEENA TRAIN June 30, 2022 – 8 Days 13 Meals Included: 5 breakfasts, 5 lunches, 3 dinners Includes grizzly bear watching at Fares per person: Khutzeymateen Sanctuary $3,265 double/twin; $3,835 single; $3,095 triple Please add 5% GST. Explore the stunning North Coast by land BC Seniors (65 & over): $115 discount with BC Services and sea! The 500-kilometre journey from Card; must book by April 28, 2022. Port Hardy to Prince Rupert aboard BC Experience Points: Ferries’ Northern Expedition takes 15 Earn 76 points on this tour. hours, all in daylight to permit great view- Redeem 76 points if you book by April 28, 2022. ing of the rugged coastline and abundant Departures from: Victoria wildlife. In Prince Rupert, we thrill to a 7- hour catamaran excursion to the Khutzeymateen Grizzly Sanctuary. Then we board VIA Rail’s Skeena Train for a spectac- ular all-day journey east to Prince George in deluxe ‘Touring Class’ with seating in the dome car. Experience the mighty Fraser River with a jetboat ride through Fort George Canyon. Then we drive south through the Cariboo with a visit to the historic gold rush town of Barkerville. Our last night is at the popular Harrison Hot Springs Resort with entertainment in the Copper Room. This is a wonderful British Columbia circle tour! ITINERARY Day 1: Thursday, June 30 seals, sea lions, bald eagles, and blue herons as We drive north on the Island Highway, past we learn first-hand about this diverse marine en- Campbell River to Port Hardy. -

Indian and Non-Native Use of the Bulkley River an Historical Perspective

Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians DFO - Library i MPO - Bibliothèque ^''entffique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I IIII III II IIIII II IIIIIIIIII II IIIIIIII 12020070 INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE by Brendan O'Donnell Native Affairs Division Issue I Policy and Program Planning Ir, E98. F4 ^ ;.;^. 035 ^ no.1 ;^^; D ^^.. c.1 Fisher és Pêches and Oceans et Océans Cariad'â. I I Scientific Excellence • Resource Protection & Conservation • Benefits for Canadians I Excellence scientifique • Protection et conservation des ressources • Bénéfices aux Canadiens I I INDIAN AND NON-NATIVE I USE OF THE BULKLEY RIVER I AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE 1 by Brendan O'Donnell ^ Native Affairs Division Issue I 1 Policy and Program Planning 1 I I I I I E98.F4 035 no. I D c.1 I Fisheries Pêches 1 1*, and Oceans et Océans Canada` INTRODUCTION The following is one of a series of reports onthe historical uses of waterways in New Brunswick and British Columbia. These reports are narrative outlines of how Indian and non-native populations have used these -rivers, with emphasis on navigability, tidal influence, riparian interests, settlement patterns, commercial use and fishing rights. These historical reports were requested by the Interdepartmental Reserve Boundary Review Committee, a body comprising representatives from Indian Affairs and Northern Development [DIAND], Justice, Energy, Mines and Resources [EMR], and chaired by Fisheries and Oceans. The committee is tasked with establishing a government position on reserve boundaries that can assist in determining the area of application of Indian Band fishing by-laws. -

CP's North American Rail

2020_CP_NetworkMap_Large_Front_1.6_Final_LowRes.pdf 1 6/5/2020 8:24:47 AM 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 Lake CP Railway Mileage Between Cities Rail Industry Index Legend Athabasca AGR Alabama & Gulf Coast Railway ETR Essex Terminal Railway MNRR Minnesota Commercial Railway TCWR Twin Cities & Western Railroad CP Average scale y y y a AMTK Amtrak EXO EXO MRL Montana Rail Link Inc TPLC Toronto Port Lands Company t t y i i er e C on C r v APD Albany Port Railroad FEC Florida East Coast Railway NBR Northern & Bergen Railroad TPW Toledo, Peoria & Western Railway t oon y o ork éal t y t r 0 100 200 300 km r er Y a n t APM Montreal Port Authority FLR Fife Lake Railway NBSR New Brunswick Southern Railway TRR Torch River Rail CP trackage, haulage and commercial rights oit ago r k tland c ding on xico w r r r uébec innipeg Fort Nelson é APNC Appanoose County Community Railroad FMR Forty Mile Railroad NCR Nipissing Central Railway UP Union Pacic e ansas hi alga ancou egina as o dmon hunder B o o Q Det E F K M Minneapolis Mon Mont N Alba Buffalo C C P R Saint John S T T V W APR Alberta Prairie Railway Excursions GEXR Goderich-Exeter Railway NECR New England Central Railroad VAEX Vale Railway CP principal shortline connections Albany 689 2622 1092 792 2636 2702 1574 3518 1517 2965 234 147 3528 412 2150 691 2272 1373 552 3253 1792 BCR The British Columbia Railway Company GFR Grand Forks Railway NJT New Jersey Transit Rail Operations VIA Via Rail A BCRY Barrie-Collingwood Railway GJR Guelph Junction Railway NLR Northern Light Rail VTR -

Attribution, Continuity, and Symbolic Capital in a Nuxalk Community

THUNDER AND BEING: ATTRIBUTION, CONTINUITY, AND SYMBOLIC CAPITAL IN A NUXALK COMMUNITY by CHRISTOPHER WESLEY SMITH B.A., University of Alaska Anchorage, 2009 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Anthropology) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2019 © Christopher Wesley Smith, 2019 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis entitled: Thunder and Being: Attribution, Continuity, and Symbolic Capital in a Nuxalk Community submitted by Christopher Wesley Smith in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Anthropology Examining Committee: Jennifer Kramer Supervisor Bruce Granville Miller Supervisory Committee Member Additional Examiner ii Abstract This ethnography investigates how Nuxalk carpenters (artists) and cultural specialists discursively connect themselves to cultural treasures and historic makers through attributions and staked cultural knowledge. A recent wave of information in the form of digital images of ancestral objects, long-absent from the community, has enabled Nuxalk members to develop connoisseurial skills to reinterpret, reengage, and re-indigenize those objects while constructing cultural continuity and mobilizing symbolic capital in their community, the art market, and between each other. The methodologies described in this ethnography and deployed by Nuxalk people draw from both traditional knowledge and formal analysis, problematizing the presumed binary division between these epistemologies in First Nations art scholarship and texts. By developing competencies with objects though exposure and familiarity, Nuxalk carpenters and cultural specialists are driving a spiritual and artistic resurgence within their community. -

Hazelton

"i. : - ; " .~: :~." : ,i <:'-:: :-!7 "('-:.. -i(?~ .... ':?. ::[~.~{;:;271'=" ~ I + ;@ = # : ~ If: I =i IT=:'# )..: i ': "r'N " : :' = I" : ~: " ; . .;7 L : :?::iq: : : ?i C('- ;, • : . .: "4~" ". '. "¢' ' .... ,'4 ~ ,=, ;,; .... , • ~ ' .' , ' , .,;,,...' ", ,- .,... : .',',:.:i<,,-:+~'~-".-:',~-~=~*;',f% ~:;?-~ .r....':'..~.. b. ,{. "- , -.' .....='.. -.-".. ,:., . ' .:~ :IN NO] N BRI ~r.~VI J:. I 7 ~": ;= i,. :-- ~ 4IOn.X=.. = :~' :# ~{:'] ;:i • t.",:?i.:'Y':.~,:.: ,L'.'< ',-'.= ,",t; "": "L'" ~ ' ::;:~'~ '::: :':' .:..:",":..'j,::m : i,'., ~ .: ~' i '~ • '.-, - . ;.,'), :.: , .- ...... , ,, . ........ : :!7: .... ,., , .... :. "r,: :" 1 " .... " IT ' "" ' " . , . Ix ; ,: .<.. HAZELTON, 1912 ;< : • .- B~"C:"SATURDAY, MAY25, " PRICE $2.00.A:~YEAR - ' -: Chnrchi!! the ChOice ,i." :Clinion]~:"..... ~l;~dy'fiVehund,~d " • " " ..... " . :,.'~, .".. ",.- ............ '_~'~' :,'--.':11 "~'...,~::~;" ','.•"," ..'" • London: TSe belief is.geneial" ' ._ | killed.Corl~taGhsuit;of.the, lndiiin~,<0fida~vs Kihdn~ On ;-;~hu. Lhe I i . i ' ofLloyd the liberalGeorge. parryoil~11 be theleader...the> r~ : r ' : ~ -:- .... -., . , ~oad:..The~,i:~ossesare i ::i. - :. ...... ~": ~: " . firement of :Premier :Asquith~ Prospect'that:Railway.... • from" ~gi~q6~geding::d°~r:6n~d/et//ildf ": _ Popdar approval isaacorded to "':, ' ~ " -i, ':~!1 'ii:• i Popular Canadian, .ViCe-Preddent of Company. Chu,c t s naval policy.. Co.t,,ence between Repre. vanarsdOl t'dSkeena CrosS; .... : L -IS Promoted-,,Annbuncement of Appoint- sentatives of the Railways, • ing~.~ll.b~,.Accepted.:?~.( -

Tribal Nations

Dinjii Zhuu Nation : Tribal Nations Map Gwich’in Tribal Nations Map Inuvialuit Vuntut Western Artic Innuit Deguth OurOur OwnOwn NamesNames && LocationsLocations Inuvialuit woman Draanjik Gwichyaa T'atsaot'ine Iglulingmiut Teetl'it Yellow Knives Inuit family KitlinermiutCopper Inuit Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in Netsilingmiut Han Netsilik Inuit Tununirmiut Tanana Sahtú Hare Utkuhiksalingmiut Hanningajurmiut Tutchone Ihalmiut Inuit Woman & Child Akilinirmiut Kangiqliniqmiut Galyá x Kwáan Denesoline Nations: Laaxaayik Kwáan Deisleen Kwáan Chipeweyan Harvaqtuurmiut Tagish Aivilingmiut Áa Tlein Kwáan Gunaa xoo Kwáan Kaska Dena Jilkoot Kwáan Kaska Krest‘ayle kke ottine Chipeweyan band Jilkaat Kwáan Aak'w Kwáan Qaernermiut Xunaa Kwáan T'aa ku Kwáan S'aawdaan Kwáan Xutsnoowú Kwáan Kéex' Kwáan Paallirmiut Tarramiut Sheey At'iká Lingít Kwáan Shtax' héen Kwáan Des-nèdhè-kkè-nadè Nation Dene Woman Kooyu Kwáan Tahltan K'atlodeeche Ahialmiut Dene Tha' Hay River Dene Sanyaa Kwáan Slavey Sayisi Dene Siquinirmiut Takjik'aan Kwáan Lingít Men WetalTsetsauts Hinya Kwáan Nisga'a Inuit Hunter Tsimshian Kaí-theli-ke-hot!ínne Taanta'a Kwáan Dane-zaa Thlingchadinne Itivimiut Sikumiut K'yak áannii Tsek’ene Beaver Gáne-kúnan-hot!ínne Dog Rib Sekani Etthen eldili dene Gitxsan Lake Babine Wit'at Haida Gitxaala Thilanottine Hâthél-hot!inne Xàʼisla Haisla Nat'oot'en Wet'suwet'en Hoteladi Iyuw Imuun Beothuk WigWam Nuxalk Nation: Nihithawiwin Bella Coola Woodlands Cree Sikumiut man DakelhCarrier Tallheo Aatsista Mahkan, HeiltsukBella Bella Siksika chief Kwalhna Stuic Blackfoot Nation -

Hazeltons, British Columbia

FOLLOW THE Hands of History Follow the “Hands of History”… The Hazeltons, British Columbia Muldoe Road (Muldoon Rd) Welcome to one of British your pace, the tour will Kispiox Rodeo Grounds Columbia’s most historic take 4 to 8 hours. (Dean Road) and scenic areas. Immerse Seventeen Mile Road Kispiox River The route is described in yourself in centuries of Date Creek two segments, each com- Forest Service Rd First Nations culture and Swan Lake Rd mencing at the Visitor learn dramatic tales of Skeena River pioneer settlement by taking the “Hands of His- GITANYOW - Hand of History Sign location KISPIOX tory” self-guided driving (Kitwancool) tour. The Tour is marked - Tour part 1 Gitanyow Road - Tour part 2 by a series of distinctive - Tourism feature “Hand of History” sign- 37 Kispiox Valley Rd GLEN VOWELL posts. Each of these mark- N ers displays a Gitxsan Kitwanga River design of peace, an open GITANMAAX hand, and a short de- HAZELTON TWO MILE Ksan Bulkey River HAGWILGET scription of a person, his- Ross Lake Provincial Park SOUTH Six Mile Lake torical event, or landform HAZELTON Hazelton-Kitwanga Backroad NEW Bulkey River that played an important Ross Lake Rd (Road ends here) HAZELTON part in the history of the Braucher Rd KITWANGA Kitwanga Fort National Historic Site Seeley Lake Upper Skeena region. Provincial Park 16 The entire Tour covers To Terrace GITWANGAK To Moricetown 150 miles or 240 kilome- Skeena River and Smithers tres but is easily modifi ed 16 Skeena Crossing Rd to fi t your schedule and Skeena Crossing interests. -

British Columbia British

BC Newcomers’ Guide to Resources and Services Resources Guide to BC Newcomers’ British Columbia Newcomers’ Guide to Resources and Services Vernon Edition 2014 Edition Please note 2014 Vernon Edition: The information in this guide is up to date at the time of printing. Names, addresses and telephone numbers may change, and publications go out of print, without notice. For more up-to-date information, please visit: www.welcomebc.ca This guide has been written using the Canadian Language Benchmark 4 (CLB 4) level to meet the needs of non-English speaking newcomers. To order copies of the Acknowledgements Provincial Newcomers’ Guide (2014 Edition) The Vernon edition of the BC Newcomers’ Guide • Shelley Motz and Timothy Tucker, Project Managers is available online at www.welcomebc.ca. Print • Barbara Carver, Baytree Communications, copies may be available through Vernon and District Project Coordinator and Editor Immigrant Services Society www.vdiss.com • Brigitt Johnson, 2014 Update Consultant Print copies of the provincial guide are available free • Reber Creative, Design Update and Layout of charge while quantities last. The provincial guide is also available online in the following languages: • Andrea Scott, Big Red Pen, Proofreading Arabic, Chinese (Simplified), Chinese (Traditional), • Gillian Ruemke-Douglas and Nola Johnston, Farsi (Persian), French, Korean, Punjabi, Russian, Illustrations Spanish and Vietnamese. You can order copies of the provincial guide by filling in the resource order form at: www.welcomebc.ca/ newcomers_guide/newcomerguide.aspx. You can also Library and Archives Canada request copies by telephone or e-mail. Please include Cataloguing in Publication Data your contact name, address, postal code and phone Main entry under title: number with “B.C. -

First Nations Pronunciations

A Basic Guide to Names* Listed below are the First Nations Peoples as they are generally known today with a phonetic guide to common pronunciation. Also included here are names formerly given these groups, and the language families to which they belong. People Pronunciation Have Been Called Language Family Haida Hydah Haida Haida Ktunaxa Tun-ah-hah Kootenay Ktunaxa Tsimshian Sim-she-an Tsimshian Tsimshian Gitxsan Git-k-san Tsimshian Tsimshian Nisga'a Nis-gaa Tsimshian Tsimshian Haisla Hyzlah Kitimat Wakashan Heiltsuk Hel-sic Bella Bella Wakashan Oweekeno O-wik-en-o Kwakiutl Wakashan Kwakwaka'wakw Kwak-wak-ya-wak Kwakiutl Wakashan Nuu-chah-nulth New-chan-luth Nootka Wakashan Tsilhqot'in Chil-co-teen Chilcotin Athapaskan Dakelh Ka-kelh Carrier Athapaskan Wet'suwet'en Wet-so-wet-en Carrier Athapaskan Sekani Sik-an-ee Sekani Athapaskan Dunne-za De-ney-za Beaver Athapaskan Dene-thah De-ney-ta Slave(y) Athapaskan Tahltan Tall-ten Tahltan Athapaskan Kaska Kas-ka Kaska Athapaskan Tagish Ta-gish Tagish Athapaskan Tutchone Tuchon-ee Tuchone Athapaskan Nuxalk Nu-halk Bella Coola Coast Salish Coast Salish** Coast Salish Coast Salish Stl'atl'imc Stat-liem Lillooet Interior Salish Nlaka'pamux Ing-khla-kap-muh Thompson/Couteau Interior Salish Okanagan O-kan-a-gan Okanagan Interior Salish Secwepemc She-whep-m Shuswap Interior Salish Tlingit Kling-kit Tlingit Tlingit *Adapted from Cheryl Coull's "A Traveller's Guide to Aboriginal B.C." with permission of the publisher, Whitecap Books ** Although Coast Salish is not the traditional First Nations name for the people occupying this region, this term is used to encompass a number of First Nations Peoples including Klahoose, Homalco, Sliammon, Sechelth, Squamish, Halq'emeylem, Ostlq'emeylem, Hul'qumi'num, Pentlatch, Straits. -

Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, West-Central British Columbia

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-10-24 A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia Kuehn, Christian Kuehn, C. (2014). A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/25002 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1936 doctoral thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY A Second North American Hot-spot: Pleistocene Volcanism in the Anahim Volcanic Belt, west-central British Columbia by Christian Kuehn A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY GRADUATE PROGRAM IN GEOLOGY AND GEOPHYSICS CALGARY, ALBERTA OCTOBER, 2014 © Christian Kuehn 2014 Abstract Alkaline and peralkaline magmatism occurred along the Anahim Volcanic Belt (AVB), a 330 km long linear feature in west-central British Columbia. The belt includes three felsic shield volcanoes, the Rainbow, Ilgachuz and Itcha ranges as its most notable features, as well as regionally extensive cone fields, lava flows, dyke swarms and a pluton. Volcanic activity took place periodically from the Late Miocene to the Holocene. -

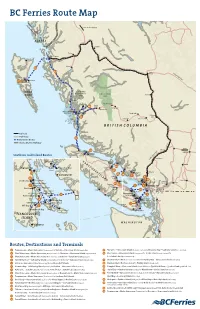

BC Ferries Route Map

BC Ferries Route Map Alaska Marine Hwy To the Alaska Highway ALASKA Smithers Terrace Prince Rupert Masset Kitimat 11 10 Prince George Yellowhead Hwy Skidegate 26 Sandspit Alliford Bay HAIDA FIORDLAND RECREATION TWEEDSMUIR Quesnel GWAII AREA PARK Klemtu Anahim Lake Ocean Falls Bella 28A Coola Nimpo Lake Hagensborg McLoughlin Bay Shearwater Bella Bella Denny Island Puntzi Lake Williams 28 Lake HAKAI Tatla Lake Alexis Creek RECREATION AREA BRITISH COLUMBIA Railroad Highways 10 BC Ferries Routes Alaska Marine Highway Banff Lillooet Port Hardy Sointula 25 Kamloops Port Alert Bay Southern Gulf Island Routes McNeill Pemberton Duffy Lake Road Langdale VANCOUVER ISLAND Quadra Cortes Island Island Merritt 24 Bowen Horseshoe Bay Campbell Powell River Nanaimo Gabriola River Island 23 Saltery Bay Island Whistler 19 Earls Cove 17 18 Texada Vancouver Island 7 Comox 3 20 Denman Langdale 13 Chemainus Thetis Island Island Hornby Princeton Island Bowen Horseshoe Bay Harrison Penelakut Island 21 Island Hot Springs Hope 6 Vesuvius 22 2 8 Vancouver Long Harbour Port Crofton Alberni Departure Tsawwassen Tsawwassen Tofino Bay 30 CANADA Galiano Island Duke Point Salt Spring Island Sturdies Bay U.S.A. 9 Nanaimo 1 Ucluelet Chemainus Fulford Harbour Southern Gulf Islands 4 (see inset) Village Bay Mill Bay Bellingham Swartz Bay Mayne Island Swartz Bay Otter Bay Port 12 Mill Bay 5 Renfrew Brentwood Bay Pender Islands Brentwood Bay Saturna Island Sooke Victoria VANCOUVER ISLAND WASHINGTON Victoria Seattle Routes, Destinations and Terminals 1 Tsawwassen – Metro Vancouver