Laparoscopic Sacralcolpopexy and Enterocele Repair with Mesh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamental Shoulder Exercises

FUNDAMENTAL SHOULDER EXERCISES RANGE OF MOTION EXERCISES 1. L-BAR FLEXION Lie on back and grip L-Bar between index finger and thumb, elbows straight. Raise both arms overhead as far as possible keeping thumbs up. Hold for _____ seconds and repeat _____ times. 2. L-BAR EXTERNAL ROTATION, SCAPULAR PLANE Lie on back with involved arm 450 from body and elbow bent at 900. Grip L-Bar in the hand of involved arm and keep elbow in flexed position. Using unin- volved arm, push involved arm into external rotation. Hold for _____ seconds, return to starting position. Repeat _____ times. 3. L-BAR INTERNAL ROTATION, SCAPULAR PLANE Lie on back with involved arm 450 from body and elbow bent at 900. Grip L-Bar in the hand of involved arm and keep elbow in flexed position. Using the uninvolved arm, push involved arm into internal rotation. Hold for _____ seconds, return to starting position. Repeat _____ times. Dr. Meisterling (800) 423-1088 1 of 2 STRENGTHENING EXERCISES 1. TUBING, EXTERNAL ROTATION Standing with involved elbow fixed at side, elbow bent to 900 and involved arm across the front of the body. Grip tubing handle while the other end of tubing is fixed. Pull out with arm, keeping elbow at side. Return tubing slowly and controlled. Perform _____ sets of _____ reps. 2. TUBING, INTERNAL ROTATION Standing with elbow at side fixed at 900 and shoulder rotated out. Grip tubing handle while other end of tubing is fixed. Pull arm across body keeping elbow at side. Return tubing slowly and controlled. -

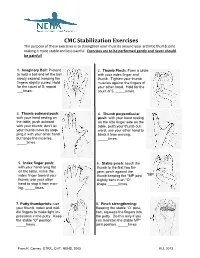

CMC Stabilization Exercises the Purpose of These Exercises Is to Strengthen Your Muscles Around Your Arthritic Thumb Joint Making It More Stable and Less Painful

CMC Stabilization Exercises The purpose of these exercises is to strengthen your muscles around your arthritic thumb joint making it more stable and less painful. Exercises are to be performed gently and never should be painful! 1. Imaginary Ball: Pretend 2. Thumb Pinch: Form a circle to hold a ball and let the ball with your index finger and slowly expand, keeping the thumb. Tighten your thumb fingers slightly curled. Hold muscles against the fingers of for the count of 5, repeat your other hand. Hold for the ___times. count of 5, _____times. 3. Thumb outward push: 4. Thumb perpendicular with your hand resting on push: with your hand resting the table, push outward on the little finger side on the with your thumb; don’t let table, push your thumb out- your thumb move by stop- ward; use your other hand to ping it with your other hand block it from moving. but tense the muscles. _____times. _____times. 5. Index finger push: 6. Stable pinch: touch the with your hand lying flat thumb to the first two fin- on the table, move the gers; pinch against the index finger toward your thumb keeping the *MP joint *MP thumb; use your other slightly bent in an “O” hand to stop it from mov- shape. _____times. ing. _____times. 7. Putty thumbprints: use 8. Pinch strengthening: your thumb, index and mid- Keeping the stable “O” posi- dle fingers to make light im- tion, squeeze the fingers into pressions in the putty. Keep the putty. Do this only if you the stable “O” position. -

Post-Operative Instructions for Flexor Tendon Repair Purpose of Surgery

Post-Operative Instructions for Flexor Tendon Repair Purpose of surgery The goal of the operation is to repair or reattach lacerated or detached flexor tendons. The flexor tendons (muscles) are responsible for flexing (bending) your fingers. What to expect after surgery? You will have a firm splint covering your forearm and the back of your hand and fingers holding your fingers flexed (bent). All your fingers will be included in the splint for any finger flexor tendon repair; and, only your thumb will be included in the splint for a thumb flexor tendon repair. You will be able to see the tips of your fingers/thumb to insure they are getting good circulation. The palm side of your fingers/thumb will be protected by a soft padding that they will be resting on while the plaster will keep your fingers bent from the nail side. You may have some numbness or tingling of fingers/thumb due to the local anesthetic injections used to help control post-operative pain (this should wear off within about 24 hours). After this first 24 hours, you may still experience some numbness and tingling in parts of the operative finger(s)/thumb if you also had a nerve repair. What should you do to help recover? While we do not anticipate significant swelling following this procedure, it would be helpful to keep your hand/wrist elevated as best you can for the first 24 hours after surgery. The thickness of the dressing will prevent the effective placement of a cold-pack. Please do not move your fingers, even if they were not operated on. -

Self Range of Motion Exercises for Arm and Hand

Self-Range of Motion Exercises for the Arm and Hand After a stroke, it is important to do the exercises in this handout for your affected arm and hand. You can do them on your own by using your unaffected arm and hand. These gentle movements are called “self-range of motion” exercises, and they help to maintain your movement, prevent stiffness, improve blood flow, and increase awareness of your affected arm and hand. Complete the exercises slowly and do not force movements. Stop if you feel pain. If you have any questions or concerns, please contact your Occupational Therapist: _______________________________ Do the exercises in this handout _____ times each day. Page - 1 Self-range of motion exercises for the arm and hand 1. Shoulder: Forward Arm Lift Interlock your fingers, or hold your wrist. With your elbows straight and thumbs facing the ceiling, lift your arms to shoulder height. Slowly lower your arms to starting position. Hold for ____ seconds. Repeat ____ times. Page - 2 Self-range of motion exercises for the arm and hand 2. Shoulder: “Rock the Baby” Stretch Hold your affected arm by supporting the elbow, forearm and wrist (as if cradling a baby). Slowly move your arms to the side, away from your body, lifting to shoulder height. Repeat this motion in the other direction. Slowly rock your arms side-to-side, and keep your body from turning. Repeat ____ times. Page - 3 Self-range of motion exercises for the arm and hand 3. Shoulder: Rotation Stretch Interlock your fingers, or hold your wrist. With your elbows bent at 90 degrees, keep your affected arm at your side. -

Upper Extremity Extensor Tendon Repair Protocol

Department of Rehabilitation Services Primary Upper Extremity and Hand Extensor Tendon Repair Protocol This protocol is not intended to be a substitute for one’s clinical decision making regarding the progression of a patient’s post-operative course based on their physical exam/findings, individual progress, and/or the presence of post-operative complications. If a clinician requires assistance in the progression of a patient, they should consult with the referring surgeon. The time frames of phases I-IV are examples and can be adjusted based on the given procedure. Progression to the next phase based on the clinical criteria and/or time frames, as appropriate. MALLET FINGER: ZONE I: Over the distal phalangeal joint (DIP)-Mallet deformity ZONE II: Over the middle phalanx/triangular ligament Goal: Protect extensor zone I and II with DIP held in extension with PIP joint free. Photo: Wikem.org/w/index.php?title Precautions: During orthotic/cast check out, keep DIP joints fully extended 100%. Frequency: one to two times/week for 6 to 10 weeks if needed for orthosis/cast checks. Primary Extensor Tendon Repair Protocol Copyright © 2020 The Brigham and Women's Hospital, Inc., Department of Rehabilitation Services. All rights reserved 1 PHASE ORTHOTIC THERAPEUTIC EXERCISE: CONSIDERATIONS: ongoing treatment is variable. Phase I immediate phase: Orthosis or circumferential cast Active PIP flexion of affected Patient to perform daily skin day 1 to 6 to 8 weeks. finger with adjacent finger(s) held check while keeping DIP Non-op: DIP 10°-0 in extension. extended. hyperextension for tendinous mallet 6-8 weeks. Consider taping DIP in extension. -

De Quervain's Tenosynovitis

PATIENT & CAREGIVER EDUCATION De Quervain's Tenosynovitis This information explains the causes, symptoms, and treatment of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis (da-cur-vains teno-sin-o-vitis). De Quervain’s tenosynovitis is a common and painful condition that affects the tendons (tissue that connects muscles to bones) of the wrist. A tendon sheath (protective covering) wraps around these tendons so that they can slide easily (see Figure 1). This allows you to turn your wrist, grip, and pinch with your hand. With de Quervain’s tenosynovitis, the tendon sheath becomes swollen. This causes pain and limited movement in your wrist and thumb. Figure 1. Wrist with De Quervain’s tenosynovitis Causes of De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis Some causes of de Quervain’s tenosynovitis include: Overusing your wrist with repetitive movements, such as: Typing Knitting De Quervain's Tenosynovitis 1/4 Using a hammer Holding an infant for a long time Carrying heavy grocery bags Strain or injury to the wrist area. Conditions that cause swelling throughout the body, such as rheumatoid arthritis. Symptoms of De Quervain’s Tenosynovitis De Quervain’s tenosynovitis can cause different symptoms, such as: Pain at the side of your wrist under the base of your thumb. Moving your thumb can increase this pain. Wrist pain that has spread into your forearm and thumb. Mild swelling, redness, or warmth at your wrist. A fluid-filled cyst near the thumb side of your wrist. Your doctor can see if you have de Quervain’s tenosynovitis based on your symptoms and a physical exam. They will also ask you to do certain movements with your hand, wrist, and thumb. -

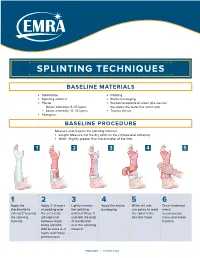

Splinting Techniques

SPLINTING TECHNIQUES BASELINE MATERIALS l Stockinette l Padding l Splinting material l Elastic bandaging l Plaster l Bucket/receptacle of water (the warmer — Upper extremity: 8–10 layers the water, the faster the splint sets) — Lower extremity: 10–12 layers l Trauma shears l Fiberglass BASELINE PROCEDURE Measure and prepare the splinting material. l Length: Measure out the dry splint on the contralateral extremity l Width: Slightly greater than the diameter of the limb 1 2 3 4 5 1 2 3 4 5 6 Apply the Apply 2–3 layers Lightly moisten Apply the elastic While still wet, Once hardened, stockinette to of padding over the splinting bandaging. use palms to mold check extend 2" beyond the area to be material. Place it the splint to the neruovascular the splinting splinted and and fold the ends desired shape. status and motor material. between digits of stockinette function. being splinted. over the splinting Add an extra 2–3 material. layers over bony prominences. EMRA.ORG | 972.550.0920 POSTERIOR LONG ARM VOLAR SPLINT SPLINT INDICATIONS INDICATIONS l Olecranon fractures l Soft tissue injuries of the hand and wrist l Humerus fractures l Carpal bone fractures l Radial head and neck fractures l 2nd–5th metacarpal head fractures CONSTRUCTION CONSTRUCTION l Start at posterior proximal arm l Start at palm at the metacarpal heads l Down the ulnar forearm l Down the volar forearm l End at the metacarpophalangeal joints l End at distal forearm APPLICATION APPLICATION l Cut hole in stockinette for thumb l Cut hole in stockinette for thumb l Elbow at 90º -

Common Elbow Injuries Symptoms

During the summer months, many people stay active by playing golf or tennis. These sports, however, carry a risk of injury to the tendons – bands of tissue that connect muscles to bones – in the elbow. This month’s AT Corner will explain how these injuries happen, how to treat them if they occur and, most importantly, how to prevent them. Common Elbow Injuries Tendonitis: Inflammation, pain and difficulty using the joint caused by repetitive activities and/or sudden trauma. Tendonosis: A degeneration (breakdown) or tear of tendons which occurs as a result of aging. Symptoms of tendonosis usually last more than a few weeks. Note: Your risk of tendonitis and tendonosis increases with age. They also occur more frequently in those who routinely perform activities that require repetitive movement, as this places greater amounts of stress on the tendons. Tennis elbow: Also referred to as lateral epicondylitis, this condition occurs when there is an injury to the outer elbow tendon. Golfers’ elbow: Also referred to as medial epicondylitis, this condition occurs when there is an injury to the inner elbow tendon. Note: Injuries to these tendons can occur in other sports and activities that use the wrist and forearm muscles. Most times, the dominant arm is the one affected. Symptoms • Pain that spreads from the elbow into the upper arm or down the forearm • Forearm weakness • Pain that can begin suddenly or gradually worsen over time • Difficulty with activities that require arm strength Treatment Over-the-counter medications: NSAIDs, such as ibuprofen (Advil®, Motrin®) and naproxen (Aleve®), or acetaminophen (Tylenol®) can provide pain relief. -

Information for Patients About Hand & Elbow Surgery

Information for Patients about Hand & Elbow Surgery Clinical Professor Allan Wang FRACS PhD FAOrthA Shoulder and Upper Limb Surgeon www.allanwangorthopaedics.com.au MURDOCH SUBIACO Murdoch Orthopaedic Clinic St John of God Subiaco Clinic St John of God Murdoch Clinic Suite 302, 25 McCourt St Suite 10, 100 Murdoch Drive Subiaco WA 6008 Murdoch WA 6150 Telephone: 08 6332 6390 Page | 2 Page | 3 Information for Patients about Hand and Elbow Surgery Introduction We have put this information booklet together to educate our patients about their Hand and Elbow condition, treatment options and post-surgical care. Please keep this booklet for future reference. It is not a detailed source of information and you may also wish to refer to our website www.allanwangorthopaedics.com.au for animated videos of surgical procedures. If you require further information or have concerns regarding your treatment please contact the office to discuss with Dr Wang or his staff. Contents Pages 1. Carpal Tunnel Syndrome 4 2. Cubital Tunnel Syndrome 6 3. Trigger Finger 7 4. De Quervain’s Tenodonitis 8 5. Ganglion Cysts 9 6. Arthritis at the Base of the Thumb 10 7. Wrist Arthroscopy 11 8. Dupuytren’s Disease 12 9. Lateral Epicondylitis 13 10. Elbow Arthroscopy 14 11. Post-Operative Instructions Hand & Elbow Surgery 15 Page | 4 Carpal Tunnel Syndrome What is it? Figure 1 Carpal tunnel syndroe is a condition aused by copression o te median nerve at te level o te wrist oint Here te edian nerve passes into te arpal tunnel along wit leor tendons and te tendon lining called tenosynoviu Carpal tunnel syndroe ocurs wen pressure builds up in te tunnel and tis an be due to swelling o te tenosynoviu ratures artritis luid retention during pregnany and certain conditions suc as diabetes and tyroid disease Symptoms en te pressure on te edian nerve becoes severe, you ay notice wrist pain tingling and nubness and lusiness in and oveents. -

Shoulder, Elbow, Wrist, & Hand Releases

Shoulder, Elbow, Wrist, & Hand Releases This series of exercises for the shoulder, elbow, wrist, and hand release tension, relieve pain, and prevent and alleviate carpal tunnel syndrome, tennis elbow, golfer's elbow, frozen shoulder, and thoracic outlet syndrome. Note: Each of these exercises can be practiced by itself, or as part of another series that you put together. When you do teach this series, it is beneficial to teach the Side Curl and Diagonal Curl first so the student can release their entire pattern of tension on that side of their torso. EXERCISE DESCRIPTION Starting Position: Lie down on the floor on your carpet or exercise mat. Bend your knees and put your feet on the floor, a comfortable hip width distance apart. Rest your hands on the floor by your sides. Bent Arm Rotation: Bend your right arm at a 90 degree angle, and keeping your elbow next to your body, let your right hand rest out to the side on the floor with your palm facing up. Then, keeping your right elbow on the floor, slowly rotate your shoulder inward. Your shoulder will press off the floor and your hand will lift up. You should feel the muscles on the front of your shoulder contracting. Then, slowly release to the count of 16. As you lower down, you should feel the muscles on the front of your shoulder slowly and gently releasing. Repeat this movement if you wish. Now, slide your arm upward on the floor, so that your elbow is pointing straight out from your shoulder. You should still have a 90 degree angle at your elbow. -

De Quervain's Tenosynovitis

de Quervain’s Tenosynovitis What is it? de Quervain’s tenosynovitis refers to inflammation of the soft tissues surrounding the tendons that move the thumb – it is an overuse injury. de Quervain’s tenosynovitis affects two thumb tendons. These tendons are responsible for extending the thumb backwards and for moving the thumb away from the palm of the hand. These tendons connect their respective muscles in the forearm to the thumb. On their way to the thumb, the tendons slide through a thick fibrous sheath that forms a tunnel. Normally the tendons glide easily back and forth within this tunnel but in de Quervain’s tenosynovitis the tunnel is tight and irritates the tendons. See figure 1. Figure 1 What are the symptoms? How did I get it? What should I do? de Quervain’s tenosynovitis results Repetitive or unaccustomed use of Left untreated, this friction-induced in pain and tenderness over the the thumb that involves pinching tenosynovitis can progress to fibrosis thumb tendons as they cross the top with the thumb while moving the and lack of flexibility of the thumb. wrist (e.g., gripping and grasping) of the wrist joint. Here the tendons It generally does not get better leads to thickening of the fibrous may also be swollen. Pinch grasping without medical intervention. tendon sheath. Thickening results in and when the thumb and wrist are You should avoid activities which inflammation and tightening as the moved causes pain. Crepitus or aggravate or provoke your pain. tendon sheath passes over the wrist creaking of the tendons may also be These may lead to further rubbing of bone. -

Hand, Wrist and Elbow Problems: How to Spot Them in Clinic

11/27/2017 HAND, WRIST AND ELBOW PROBLEMS: HOW TO SPOT THEM IN CLINIC Nicolas H. Lee, MD [email protected] UCSF Dept of Orthopaedic Surgery Assistant Clinical Professor Hand, Upper Extremity and Microvascular Surgery Dec. 3rd, 2017 Disclosures Research Support: San Francisco DPH Standard Cyborg 1 11/27/2017 DIP joint pathologies 1. Mucous Cyst 2. Mallet Finger 3. Jersey Finger Mucous Cyst – ganglion cyst of DIP joint 2 11/27/2017 Xray 3 11/27/2017 Treatment • Recurrence rate with aspiration/needling? 40-70% • Recurrence rate with surgical debridement of osteophyte? 0-3% • Do nail deformities resolve with surgery? Yes - 75% “Jammed Finger” Mallet Finger Jersey Finger 4 11/27/2017 Mallet Finger Soft Tissue Mallet Bony Mallet http://www.specialisedhandtherapy.com.au/ Mallet finger • 6 weeks DIP immobilization in extension • Night time splinting for 4 weeks 5 11/27/2017 Red Flag Mallet Finger When to Refer: 1. Big fragment 2. Volar subluxation of the distal phalanx Red Flag Jersey Finger Flexor Digitorum Profundus (FDP) strength testing http://nervesurgery.wustl.edu/ http://www.orthobullets.com REFER ALL JERSEY FINGERS ASAP!!! 6 11/27/2017 Trigger Finger and Thumb Trigger finger • Presentation • Clicking or frank locking • Especially at night or morning • May also present with just pain at the A1 pulley 7 11/27/2017 Trigger Finger • Physical Examination • Locking or clicking over the A1 pulley • Tenderness at the A1 pulley Primary Trigger Finger • Most Common • “Idiopathic” • No known cause 8 11/27/2017 Secondary • Associated with known disease • Disease cause thickening in tendon/pulley • Diabetes • Rheumatoid arthritis • Amyloidosis • Sarcoidosis “Congenital” • Infantile form • “congenital” is a misnomer 9 11/27/2017 Treatment Options •Nonoperative •Observation •Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication Studies show •Splinting steroid injection alone is more •Corticosteroid injection effective than splints •Operative release Trigger finger Splinting • Splint to prevent MCP or PIP flexion.