NRC-057 Submitted: 5/8/2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cultural Heritage Form

This form may be used to document and initially record traditional cultural properties, sacred sites, and/or sites of cultural and religious significance to tribes or other groups. The form is not a formal determination of significance by Federal, Tribal, or State officials. Revised July 2013 CULTURAL HERITAGE FORM Revised July 2013 The Cultural Heritage Form may be used to document and initially record traditional cultural properties, sacred sites, and / or sites of cultural and religious significance to tribes or other groups. This form is not a formal determination of significance by Federal, Tribal, or State officials. The Cultural Heritage Form is not required by the North Dakota State Historic Preservation Office (NDSHPO) or the State Historical Society of North Dakota (SHSND). The Cultural Heritage Form is not a substitute for the North Dakota Cultural Resource Survey (NDCRS) archaeological, architectural, and historical archaeological site forms. Locations identified and recorded on the Cultural Heritage Form will not be assigned a formal Smithsonian Institution Trinomial System (SITS) site number. THE CULTURAL HERITAGE FORM Temporary Number: If needed, a temporary identification number used by the Recorder. Identification Number: A permanent identification number. Corresponding SITS# (if applicable): If the site also is recorded with the North Dakota Cultural Resource Survey (NDCRS), provide the corresponding Smithsonian Institutional Trinomial System (SITS) number for cross-reference. Map Quad(s): The name(s) of the USGS 7.5' topographic quadrangle(s) on which the site is plotted. Legal Description LTL: Due to surveyor errors made during the platting of the state of North Dakota, certain areas of Richland and Sargent counties contain township numbers that are duplicated within the Sisseton-Wahpeton Dakota Nation. -

Eriogonum Visheri A

Eriogonum visheri A. Nelson (Visher’s buckwheat): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project December 18, 2006 Juanita A. R. Ladyman, Ph.D. JnJ Associates LLC 6760 S. Kit Carson Cir E. Centennial, CO 80122 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Ladyman, J.A.R. (2006, December 18). Eriogonum visheri A. Nelson (Visher’s buckwheat): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http://www.fs.fed.us/r2/ projects/scp/assessments/eriogonumvisheri.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The time spent and help given by all the people and institutions listed in the reference section are gratefully acknowledged. I would also like to thank the North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department, in particular Christine Dirk, and the South Dakota Natural Heritage Program, in particular David Ode, for their generosity in making their records, reports, and photographs available. I thank the Montana Natural Heritage Program, particularly Martin Miller, Mark Gabel of the Black Hills University Herbarium, Robert Tatina of the Dakota Wesleyan University, Christine Niezgoda of the Field Museum of Natural History, Carrie Kiel Academy of Natural Sciences, Dave Dyer of the University of Montana Herbarium, Caleb Morse of the R.L. McGregor Herbarium, Robert Kaul of the C. E. Bessey Herbarium, John La Duke of the University of North Dakota Herbarium, Joe Washington of the Dakota National Grasslands, and Doug Sargent of the Buffalo Gap National Grasslands - Region 2, for the information they provided. I also appreciate the access to files and assistance given to me by Andrew Kratz, Region 2 USDA Forest Service, and Chuck Davis, U.S. -

The Importance of the Museum in Antebellum US Western Territorial

University of North Dakota UND Scholarly Commons Datasets 2021 Appendices to "The importance of the museum in antebellum U.S. western territorial exploration: Part 2. The roles of Hayden and Meek in a paradigm shift in geologic and paleontologic studies" Joseph A. Hartman University of North Dakota, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.und.edu/data Part of the Geology Commons Recommended Citation Hartman, Joseph A., "Appendices to "The importance of the museum in antebellum U.S. western territorial exploration: Part 2. The roles of Hayden and Meek in a paradigm shift in geologic and paleontologic studies"" (2021). Datasets. 20. https://commons.und.edu/data/20 This Data is brought to you for free and open access by UND Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Datasets by an authorized administrator of UND Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TABLE App-1. HAYDEN'S "CATALOG OF MINERALS AND GEOLOGICAL SPECIMENS" Includes "II. Sedimentary Rocks" [Excludes I. Igneous and Metamorphic Rocks] Hayden (1862, Chapter XIV, p. 133‐137; with annotations; Same numbered specimens as Hayden, 1858 [1875]) Catalog data organized by state traveling downriver and going upsection. Localities/specimens within states are organized by upriver and upsection (as much as possible). Hayden most likely did not collect each specimen from the same location. Thus "specimen" numbers are effectively localities. Hayden entries are reorganized by primary lithology, followed by descriptive information. Data, spellings, stratigraphy, and nomenclature are of Hayden; annotations are given for clarity (e.g., name changes, locations). -

View Carol's Service Folder

In Loving Memory Of Carol Margaret Elk Nation Pte’ Wašte’ Win (Pretty Buffalo Woman) May 28, 1958 November 25, 2020 Eagle Butte, South Dakota Rapid City, South Dakota Maggie May FUNERAL SERVICE: 11:00 a.m., Monday, December 7, 2020 All Saints Catholic Church ~ Eagle Butte, South Dakota Wake up, Maggie, I think I got somethin’ to say to you OFFICIANT: Fr. John Paul Trefz It’s late September and I really should be back at school’ CASKET BEARERS: Charles White Eagle, Todd Heideman, Shayden Marshall, Hoksila White Mountain, Todd Johns, Levi Elk Nation, Fain Iron Bird, I know I keep you amused, but I feel I’m being used Tyson Maxon, and Tyson Lecompte-Garreaux HONORARY CASKET BEARERS: CR Health Center EMT and E.R. Staff, Monument Oh, Maggie, I couldn’t have tried any more Health Staff, Karil Harmon, Sherri Red Fox, Esther Thompson, Coty and Pam Garreau, Peggy Jo McLaughlin, Ronda Pearman and Martin Chasing Hawk, Stevie Garreau, Cathy Jeffries, Sage You led me away from home Jeffries, Stephanie Davidson and Family, Carson Mound and Family, Jack and Rita Claymore, Mary Marshall and Family, Sandy Ward, Ron & Nita Pearman, Hoss, Chad and L Jay Pearman, Just to save you from being alone Tudee and Gary Rousseau, Gib Marshall, Kris O’Rourke, Kevin and Marla Keckler and Family, Kristina, Robin Elk Head, Blue Lofton, D’Lani Lecompte, Eddie Hoffman, Wanda Lind and Family, You stole my heart and that’s what really hurts Bernie Halfred and Family, Jess Keckler and Family, Faye “Cowgirl” High Elk, Dani Cudmore, Sandy Runs After, Paula Hill, Raylene Miner, Bernita In The Woods, Inez Iron Bird and Family, The mornin’ sun when it’s in your face really shows your age Bev and Delmar Clown and Family, Delmar, Jr. -

Where the West Begins? Geography, Identity and Promise

Where the West Begins? Geography, Identity and Promise Papers of the Forty-Seventh Annual DAKOTA CONFERENCE A National Conference on the Northern Plains Cover illustration courtesy of South Dakota Department of Tourism THE CENTER FOR WESTERN STUDIES AUGUSTANA 2015 Where the West Begins? Geography, Identity and Promise Papers of the Forty-Seventh Annual Dakota Conference A National Conference on the Northern Plains The Center for Western Studies Augustana Sioux Falls, South Dakota April 24-25, 2015 Compiled by: Erin Castle Nicole Schimelpfenig Financial Contributors Loren and Mavis Amundson CWS Endowment/SFACF City of Deadwood Historic Preservation Commission Tony & Anne Haga Carol Rae Hansen, Andrew Gilmour & Grace Hansen-Gilmour Gordon and Trudy Iseminger Mellon Fund Committee of Augustana College Rex Myers & Susan Richards CWS Endowment Joyce Nelson, in Memory of V.R. Nelson Rollyn H. Samp, in Honor of Ardyce Samp Roger & Shirley Schuller, in Honor of Matthew Schuller Robert & Sharon Steensma Blair & Linda Tremere Richard & Michelle Van Demark Jamie & Penny Volin Ann Young, in Honor of Durand Young National Endowment for the Humanities Cover illustration Courtesy South Dakota Department of Tourism ii Table of Contents Preface ........................................................................................................................... vi Anderson, Grant K. A Schism Within the Nonpartisan League in South Dakota .................................................................... 1 Bakke, Karlie Violence and Discrimination -

Cheyenne River Agency (See Also Upper Platte Agency)

Cheyenne River Agency (see also Upper Platte Agency) Established in 1869, this agency is sometimes called the Cheyenne Agency. The agency was located on the west bank of the Missouri River below the mouth of the Big Cheyenne River, about six miles from Fort Sully. The following Lakota bands settled at Cheyenne Agency: Miniconjou, Sihasapa, Oohenunpa, and Itazipco. Headmen at this agency included: Lone Horn, Red Shirt, White Swan, Duck, and Big Foot of the Miniconjou; Tall Mandan, Four Bears, and Rattling Ribs of the Oohenunpa; and Burnt Face, Charger, Spotted Eagle, and Bull Eagle of the Itazipco. Today the reservation is located in north-central South Dakota in Dewey and Ziebach counties. The tribal land base is 1.4 million acres with the eastern boundary being the Missouri River. Major communities include Cherry Creek, Dupree, Eagle Butte, Green Grass, Iron Lightning, Lantry, LaPlant, Red Scaffold, Ridgeview, Thunder Butte, and White Horse. Arvol Looking Horse, 19th generation keeper of the Sacred Pipe of the Great Sioux Nation, lives at Green Grass. Collections ACCESSION # DESCRIPTION LOCATION H76-105 Chief’s Certificates, 1873-1874 (Man Afraid of His Box 3568A Horses, Red Cloud, Red Dog, High Wolf) Indian Register, 1876 This register contains a census of Indians on the Cheyenne River Agency in 1876. The original is the property of the National Archives and was microfilmed at the request of the South Dakota State Historical Society in 1960. CONTENTS MF LOCATION Cheyenne River Agency Indian Register, 1876 9694 (Census Microfilm) Indian Census Rolls, 1892-1924 (M595). Because Indians on reservations were not citizens until 1974, nineteenth and early twentieth century census takers did not count Indians for congressional representation. -

The Lignite Field of Northwestern South Dakota

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FRANKLIN K. LANE, Secretary UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEORGE OTIS SMITH, Director Bulletin 627 ^X'Vj THE LIGNITE FIELD OF NORTHWESTERN SOUTH DAKOTA BY DEAN E. WINCHESTER, C. J. HARES, E. RUSSELL LLOYD, AND E. M. PARKS WASHINGTON GOVEENMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1916 ADDITIONAL COPIES OF THIS PUBLICATION MAY BE PROCURED FROM THE SUPERINTENDENT OF DOCUMENTS GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON, D. C. AT 25 CENTS PER COPY CONTENTS. Page. Introduction............................................................... 7 Location and extent.................................................... 7 Object of the survey................................................... 7 Personnel and acknowledgments........................................ 7 Previous work......................................................... 8 Land survey........................................................... 9 Field worjc............................................................. 9 Geography.......................................:.......................... 10 Surface features........................................................ 10 Drainage and water supply.............................................. 11 Climate and vegetation................................................ 13 Settlement............................................................. 14 Geology.................................................................. 14 General outline....................................................... 14 Cretaceous system..................................................... -

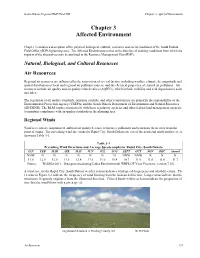

Chapter 3 Affected Environment

South Dakota Proposed RMP/Final EIS Chapter 3, Affected Environment Chapter 3 Affected Environment Chapter 3 contains a description of the physical, biological, cultural, economic and social conditions of the South Dakota Field Office (SDFO) planning area. The Affected Environment serves as the baseline of existing conditions from which the impacts of the alternatives may be analyzed in the Resource Management Plan (RMP). Natural, Biological, and Cultural Resources Air Resources Regional air resources are influenced by the interaction of several factors, including weather, climate, the magnitude and spatial distribution of local and regional air pollutant sources, and the chemical properties of emitted air pollutants. Air resources include air quality and air quality related values (AQRVs), which include visibility and acid deposition to soils and lakes. The regulation of air quality standards, emission controls, and other requirements are primarily the responsibility of the Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) and the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources (SD DENR). The BLM works cooperatively with these regulatory agencies and other federal land management agencies to maintain compliance with air quality standards in the planning area. Regional Winds Wind is a critical component of ambient air quality because it disperses pollutants and transports them away from the point of origin. The prevailing wind directions for Rapid City, South Dakota are out of the north and north-northwest, as shown in Table 3-1. Table 3-1 Prevailing Wind Directions and Average Speeds (mph) for Rapid City, South Dakota JAN FEB MAR APR MAY JUN JUL AUG SEPT OCT NOV DEC Annual NNW N N N N N N N NNW NNW N N N 11.8 12.0 12.9 13.5 12.8 11.6 11.0 10.4 10.7 11.0 11.0 11.0 11.7 Source: WebMet 2011. -

Chapter 74:51:03 Uses Assigned to Streams

Presented below are water quality standards that are in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. EPA is posting these standards as a convenience to users and has made a reasonable effort to assure their accuracy. Additionally, EPA has made a reasonable effort to identify parts of the standards that are not approved, disapproved, or are otherwise not in effect for Clean Water Act purposes. SURFACE WATER QUALITY 74:51 CHAPTER 74:51:03 USES ASSIGNED TO STREAMS Section 74:51:03:01 Beneficial uses of South Dakota streams to include irrigation and fish and wildlife propagation, recreation, and stock watering. 74:51:03:02 Beneficial uses of stream segments indicated by listings. 74:51:03:03 Segment boundaries described. 74:51:03:04 Minnesota River's tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:05 Missouri River and certain small tributaries' beneficial uses. 74:51:03:06 Bad River and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:07 Big Sioux River and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:08 Cheyenne River and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:09 Battle Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:10 The Belle Fourche River and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:11 Box Elder Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:12 Elk Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:13 Fall River and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:14 French Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:15 Lame Johnny Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:16 Pleasant Valley Creek and certain tributaries' uses. 74:51:03:17 Rapid Creek and certain tributaries' uses. -

Summits on the Air U.S.A

Summits on the Air U.S.A. (W0D – The Dakotas) Association Reference Manual Document Reference S109.1 Issue number 1.10 Date of issue 1 December 2015 Participation start date 1 April 2014 Authorised Date: 1 December 2015 obo SOTA Management Team Association Manager Randy Shirbroun, ND0C [email protected] Summits-on-the-Air an original concept by G3WGV and developed with G3CWI Notice “Summits on the Air” SOTA and the SOTA logo are trademarks of the Programme. This document is copyright of the Programme. All other trademarks and copyrights referenced herein are acknowledged. Summits on the Air Award Programme The Dakotas (W0D) Document S109.1 v1.10 Table of contents Page Section 1 Association Reference Data…………………………………………………………………4 1.1 Program Derivation ............................................................................................. 5 1.2 General Information .............................................................................................. 5 1.3 Final Ascent and Activation Zone ......................................................................... 7 1.4 Rights of Way and Access Issues ......................................................................... 8 1.5 Maps and Navigation ............................................................................................ 9 1.6 Safety Considerations ........................................................................................... 9 1.7 Navigation and Weather ..................................................................................... 10 1.8 -

Solving a Mystery, Living in Otheparts of the World, Imagining the Future, Traveling in Space, and Magic and the Supernatural

DOCUMENT RESUME BD 112 425 CS 202 279 AUTHOR Walker, Jerry L., Ed. TITLE Your Reading: A Booklist for Junior High Students. Fifth Edition. INSTITUTION National Council of leachers of English, Urbana, Ill. PUB DATE 75 NOTE 424p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Junior High School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English; Pages 419-440 containing Author Index and Title Index removed because type too small for reproduction AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Road, Urbana, Illinois 61801 (Stock No. 59370, $1.95 non-member, $1.75 member) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.76 HC-$20.94 Plus Postage DESCRIPTORS *Adolescent Literature; *Annotated Bibliographies; *Booklists; *Books; Junior High Schools; Literature; Literature Appreciation; *Reading Materials; Secondary Education ABSTRACT Written for adolescents, this most recent edition 'contains annotations for over 1,500 publications in the fiction and nonfiction categories. Most entries have been published in the past few years, though well-written older books are also included. Topics covered under fiction include books on adventure, family life, freedom, friendship, fantasy, folklore, love, what it's like to be a member of a minority group, coping with physical handicaps, growing up female, growing up male, living in America, being in sports, solving a mystery, living in otheparts of the world, imagining the future, traveling in space, and magic and the supernatural. The nonfiction section lists books about animals; adventurers; American leaders; athletes; scientists; world figures; writers; the fine arts; government; health; American and world history; hobbies; occupations; personal growth and development; places and people of the world; the sciences; social issues; sports; witchcraft; magic, and the occult; and poetry. -

Geologic Map of South Dakota Has Been a O R 18 44 Ch

South Dakota Geological Survey General Map 10 o 104o 103 102o 101o 100o 99o 98o 97o N O R T H D A K O T A Kfh C Tll rooked White Rock Creek ut12 ut12 (!73 (!25 Tll Ttr R Ttr Qlo o STATE OF SOUTH DAKOTA 27 Tll Lemmon c L Kfh Qlov (! Big Slough Tll 3 a Qlot t83 k u 0 Ttr Morristown k Kp Qlts k 0 T e Qlts e C 0 Morristown k 3 h e O e r 2 u 1804 2 Lake r Qll 0 47 e 0 M Kh n Qltg a ST 0 (! Elm r C 0 e h 0 t 0 F d Tll e 10 Qlte 0 C o 0 e (! M. Michael Rounds, Governor e Qlot Qltg 0 e 2 4 l o 1 r McIntosh 12 k Lake 1 Hecla Qlte l tf New 127 ut Qloc Qlts e r Veblen (! Bi H Tc St Kh Lake Kp r B o Ttr g a in Artas e a h 25 N v L S (! Qll w k i Qe Effington a s C Pocasse Qlov 0 W Rosholt 1 Mud 79 k 0 127 Kh ty Ttr (! Pollock 0 R (! 0 F 65 r 2 i C C (! e Qltg Qlov ld (!106 0 e l Claire 0 re a Tc e l reek Lake e r H k (!45 Rice C t E e k C e u p White r a k Tll m Kfh a City s Qloc Qltg e p M 0 t K Tc e Qloc C Qlts Lake 0 Qltm i k C r 37 e 6 m F g e Long (! DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES bl re rin ek c 1 e l p 271 a e S (! Long Qlot h n k Qloc Lake 239 c t I (! a Little r C W r Herreid n C o Qlov v e re a 0 O v e Tll 2 i n 0 Qlo i k 4 r Lake r d N 0 l 2 4 a e l 4 Hausauer R or 0 o 0 B 1 k A Steven M.