Phones, More Transfers?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Somalia-Telecoms-Mobile-And-Broadband-Statistics- And-Analyses

Report Information More information from: https://www.wiseguyreports.com/reports/98349-somalia-telecoms-mobile-and-broadband-statistics- and-analyses Somalia - Telecoms, Mobile and Broadband - Statistics and Analyses Report / Search Code: WGR98349 Publish Date: 28 August, 2018 Price 1-user PDF : $ 750.0 Enterprise PDF : $ 3000.0 Description: Somalia’s telecom sector secures a new regulator Somalia’s telecom market has been sustained despite tremendous difficulties. The country’s economy has made it difficult to sustain investment in infrastructure, and the Al Shabaab Islamic militant group has on occasion forced the closure of internet services in many areas of the country. Furthermore, there has been a lack of guidance from a central government or sector regulatory entity since 1991, when a dictatorial regime was overthrown. However, some progress may be expected following the passing of the National Communications Law in October 2017, aimed at setting a legal and regulatory framework for the telecoms sector. The Law made provision for a National Communications Agency charged with encouraging market competition and overseeing the use of ICTs in promoting economic development. A Director for the Agency was appointed in February 2018. Through the anarchy which continues to disrupt the country, the telecoms market, dominated by the competitive mobile sector where seven networks compete for customers, has flourished. Some of these mobile services operators also offer fixed-line and internet services. Tariffs are among the lowest in Africa, and although the absence of regulation led to problems with frequency spectrum coordination and interconnection between networks these issues are to be addressed by the new telecom regulator. -

Puntland Facts & Figures 2017-2018

…... DAWLADDA PUNTLAND PUNTLAND GOVERNMENT EE SOOMAALIYA OF SOMALIA Ministry of Planning & International Cooperation Wasaaradda Qorsheynta & Iskaashiga Caalamiga PUNTLAND GOVERNMENT OF SOMALIA MINISTRY OF PLANNING AND INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION DEPARTMENT OF STATISTICS PUNTLAND FACTS AND FIGURES 5th Edition 2009 i …... TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .................................................................................................................. i LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... ii LIST OF CHARTS .......................................................................................................................... v PREFACE...................................................................................................................................... ix 1.INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................................................1 1.1.Historical Background........................................................................................................1 1.2.Puntland State of Somalia.................................................................................................................. 2 1.3.Trends of Political and Constitutional Development ................................................................. 2 2.GEOGRAPHY AND CLIMATE ....................................................................................................3 -

Somalia Media and Telecoms Landscape Guide January 2012

Somalia Media and Telecoms Landscape Guide January 2012 1 Index Page Introduction................................................................................................... 3 Media overview............................................................................................ 11 Radio overview………..................................................................................20 Radio stations..............................................................................................22 TV overview..................................................................................................54 TV stations....................................................................................................56 Print media overview....................................................................................63 Main newspapers..........................................................................................64 Online media ................................................................................................70 Traditional channels of communication.....................................................76 Media resources...........................................................................................78 Telecoms overview.................................................................................. ....85 Telecoms companies...................................................................................89 2 1. Introduction Somalia has been without effective central government since 1991. Since -

Factors Influencing Mobile Money Transfer Adoption Among Somali Students

International Journal of Business, Economics and Law, Vol. 4, Issue 1 (June) ISSN 2289-1552 2014 FACTORS INFLUENCING MOBILE MONEY TRANSFER ADOPTION AMONG SOMALI STUDENTS Ali Yassin Sheikh Ali Business administration department, College of Business studies, Sudan University of Science and Technology, Sudan, Khartoum Email: [email protected] Ismail Sheikh Yusuf Dhaha Department of communication, KIRKHS, International Islamic University Malaysia (IIUM), 53100, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT Mobile Money transfer is gaining popularity among peoples in several African countries, where people are struggling for necessities of the life. In Somalia, the leading telecommunication company (Hormuud) in the capital city, Mogadishu, launched Electronic Voucher Card Plus (EVC Plus), a mobile application technology for money transfer. People including students widely adopted EVC Plus for transferring, selling/buying, sharing, and receiving money to the family members, friends, and businesses. The current study investigates the factors that influence EVC Plus adoption among students in a private university in Mogadishu, Somalia, based on extended Technology Acceptance Model (TAM). By using proportionate stratified random sampling, 414 students responded to the study. The data was collected in June 2013 and was analyzed using SPSS version 17.0. The findings indicated that perceived usefulness (β=.275, t=5.435, p<.001), perceived ease of use (β=.222, t=4.826, p<.001) and perceived trust ((β=.331, t=7.185, p<.001) had statistically significant and positive effect on intention to adopt EVC Plus among students, whereas perceived risk ((β=.059, t=1.702, p=.089) was not a predictor of intention to use EVC Plus. -

JAMA MOHAMUD ABDIAZIZ.Pdf

TELECOMMUNICATION INDUSTRY AND EMPLOYMENT CREATION IN GAROWE DISTRICT SOMALIA BY ABDIAZIIZ JAMA MOHAMUD REG: 1153-06176-01404 A THESIS REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF HUMANITIES AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OFTHE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE MASTERSDEGREE OF ARTS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY OCTOBER, 2018 i DECLARATION I, hereby declare that the research submitted to Kampala International Universityby me is my own original work. I am aware of the fact that in case my work is found to be plagiarized or not genuine, Kampala International University has the full authority to cancel my research work and I am liable to penal action. APPROVAL I certify that this dissertation has been done under my supervision and is been submitted for examination with approval as a university supervisor. i Supervisor: Dr. Wandiba Augustine ii DEDICATION I dedicate this work to my parents and family members for their moral support and the encouragement that they gave me during the study. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to acknowledge and be grateful to Allah for enabling me to reach this point in my academic life and I am so thankful for His unconditional protection. Many thanks to my supervisor Dr. Wandiba Augustine who read my numerous revisions and helped me make some sense of the project. I am also grateful to Kampala International University Hearing and Defense workshops for providing me with the conceptual means to complete this project. I wish to acknowledge my research assistants who devoted their time and energy towards the accomplishment of this research report. The moral support that they gave me too was overwhelming and came in handy at times when I was being challenged by various issues in the field. -

Somalia Media and Telecoms Landscape Guide January 2012

Somalia Media and Telecoms Landscape Guide January 2012 If you wish to suggest any updates or amendments to this document, please contact Robert Powell on [email protected] 1 Index Page Introduction................................................................................................... 3 Media overview............................................................................................ 11 Radio overview………..................................................................................20 Radio stations..............................................................................................22 TV overview..................................................................................................54 TV stations....................................................................................................56 Print media overview....................................................................................62 Main newspapers..........................................................................................63 Online media ................................................................................................69 Traditional channels of communication.....................................................75 Media resources...........................................................................................77 Telecoms overview.................................................................................. ....84 Telecoms companies...................................................................................88 -

Diaspora-Driven Development in Stateless Somalia: All Relationships Are Local Relationships

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Archived Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2009 Diaspora-driven development in stateless Somalia: all relationships are local relationships Joseph Scheibel Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Scheibel, J. (2009).Diaspora-driven development in stateless Somalia: all relationships are local relationships [Thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds/2384 MLA Citation Scheibel, Joseph. Diaspora-driven development in stateless Somalia: all relationships are local relationships. 2009. American University in Cairo, Thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/retro_etds/2384 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archived Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Science Diaspora-Driven Development in Stateless Somalia: All Relationships are Local Relationships A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Political Science In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts by Joseph Alan Scheibel B.A. in Government and International Politics, George Mason University under the supervision of Dr. Ibrahim Elnur May, 2009 The American University in Cairo DIASPORA-DRIVEN DEVELOPMENT IN STATELESS SOMALIA: ALL RELATIONSHIPS ARE LOCAL RELATIONSHIPS A Thesis Submitted by Joseph Alan Scheibel to the Department of Political Science April, 2009 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Approved by: Dr. Ibrahim Elnur Thesis Committee Chair/Advisor ________________________________ Affiliation ________________________________ Dr. -

This Report Is Financed by the European Development Fund and Implemented by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT)

EUROPEAN UNION Delegation of the European Commission Somalia Unit Somalia Urban Sector Profile Study September 2002 UN-HABITAT Regional Office for Africa and the Arab States This report is financed by the European Development Fund and implemented by the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT). The authors accept full responsibility for this report that was drawn up on behalf of the European Commission. It does not necessarily reflect the views of the European Commission. Acknowledgements: The Urban Sector Profile Study Report has been prepared by the international consultants Mr. Richard Woods and Mr. James Mutero with substantive guidance and inputs from the Regional Office for Africa and the Arab States (ROAAS), UN-HABITAT. EC-Somalia Office: Contracting authority: Gary Quince, Head of Delegation Coordination: Roger De Backer, Economic Advisor Jesper Pedersen, Technical Assistant, Urban Development and Mine Action UN-HABITAT: Coordination: Alioune Badiane, Chief, ROAAS, Mohamed El Sioufi, Senior Human Settlements Advisor Team: Sanne Willems, Pierre Gelas, Eric Verschuur, Fuaad Alkizim. Field staff: Marco Van-der Plas, Coordinator, Omar Duale, Mohamed Haibe, Liban Hussein. Design: Jennifer Chéruel (Layout), Vincent Kitio (Cover, photographs, CD-Rom). Logistics: Anne Maina, Beatrice Nyikuri, Milcah Mbindyo The team appreciates the support provided by EC Somalia Office, UN-HABITAT headquarter staff and all the partners in the field. Abstract: The Urban Sector Profile Study for Somalia has been prepared between June and September 2002. It is intended to fill a gap between the EC’s Country Support Strategy and individual urban project interventions, providing an instrument for policy dialogue and a basis for determining interventions. -

The Role of Somali Women in the Private Sector

THE ROLE OF SOMALI WOMEN IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) UNDP is the UN’s global development network, advocating for change and connecting countries to knowledge, experience and resources to help people build a better life.we provide expert advice, training, and grant support to developing countries, with increasing emphasis on assistance to the least developed countries. We are on the ground in 177 countries, working with nations on their own solutions to global and national development challenges. As they develop local capacity, they draw on the people of UNDP and our wide range of partners. Disclaimer: The study on Somali women in Private sector was commissioned by the United Nations Development Programme, Somalia Country Office. February 2014. The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the United Nations, including UNDP. Author: Lara Burger, International Consultant, following a series of interviews and review of documents, conducted with Somali men and women in public and private sector across somalia as well as UN agencies in Somalia This publication is available in English and can be found on the Internet: http://www.so.undp.org/content/somalia/en/home/library/womens_ empowerment.html All enquiries should be addressed to: UNDP Somalia U.N Common Compound (UNCC) Airport Road, Wadajir District Mogadishu Somalia Tel: +252-1-858298 Hormuud +252-5-929090 Nationlink +252-1-216111 Telcom E-mail: [email protected] There is no copyright attached to this publication. It may be reproduced in whole or in part without prior permission from the United Nations Development Programme. -

Isse Farah Hassan.Pdf

ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND EMPLOYMENT GENERATION IN THE PRIVATE SECTOR IN MOGADISHU, SOMALIA BY ISSE FARAH HASSAN MDS/39710/131/DF A THESIS REPORT SUBMITTED TO THE COLLEGE OF RESEARCH AND ifiGIIER DEGREES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENT FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF MASTERS IN DEVELOPMENT STUDIES OF KAMPALA INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY MAY, 2015 DECLARATION I, Isse Farah Hassan, declare that this thesis report is my original work and has not been presented for a Degree or any other academic award in any university or institution of learning. Signed Date APPROVAL I confirm that the work in this thesis report was done by the candidate under my supervision. ___________ D—O 1 ~ Dr. Otanga R~Je Dat~ DEDICATION I dedicate this piece of work to my brother, Mohamed, my sisters, Ayan and Nasteho, my beloved wife, Ms. Samira, my son, Abdisamad, and my daughter, Hanan. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sincere gratitude is accorded to the Almighty God for the gift of life that He gave me throughout my studies. I am deeply indebted to my research supervisor, Dr. Otanga Rusoke for his patience with my inadequacies as he guided me through the research. Without his parental and professional input, this research would have been difficult to elevate to its current level. Furthermore, i acknowledge with gratitude the contributions and co-operation made by the respondents from the selected private institutions for their willingness to provide the necessary information when i visited their offices during the research process. Without their cooperation, this study would have been impossible to accomplish. I also acknowledge the authors whose works have been referenced in this study. -

List of International Signalling Point Codes (Ispc) (According to Itu-T Recommendation Q.708 (03/99))

Annex to ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1004 – 15.V.2012 INTERNATIONAL TELECOMMUNICATION UNION TSB TELECOMMUNICATION STANDARDIZATION BUREAU OF ITU _______________________________________________________________ LIST OF INTERNATIONAL SIGNALLING POINT CODES (ISPC) (ACCORDING TO ITU-T RECOMMENDATION Q.708 (03/99)) (POSITION ON 15 MAY 2012) _______________________________________________________________ Geneva, 2012 List of International Signalling Point Codes (ISPC) Note from TSB 1. This List of International Signalling Point Codes (ISPC) replaces the previous one published as Annex to the ITU Operational Bulletin No. 979 of 1.V.2011. Since then, a number of notifications have been received at TSB and they have been published separately in various issues of the ITU Operational Bulletin. The present list recapitulates all the different amendments that have been published up to ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1004 of 15.V.2012. 2. Recommendation Q.708 states that the assignment of signalling area/network codes (SANC) is to be administered by TSB. Each country will then be responsible for the assignment of international signalling point codes (ISPC) that will then be notified to TSB. 3. The numbering plan of Recommendation Q.708 contains 2 048 SANCs providing for 16 384 international signalling points. From these, currently 1 536 SANCs are available for assignment allowing for 12 288 international points. At present 962 SANCs are assigned; the reported utilization is 5 618 international signalling points. 4. In order to keep the list up to date, administrations are, therefore, requested to notify TSB, by using the notification form attached, as soon as an ISPC assignment or withdrawal is made, www.itu.int/itu-t/inr/forms/ispc.html . -

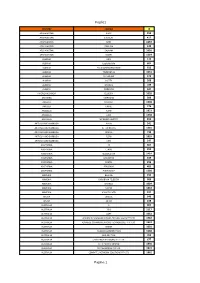

Foglio1 Pagina 1

Foglio1 COUNTRY CARRIER id AFGHANISTAN AWCC 254 AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT 417 AFGHANISTAN MTN 1263 AFGHANISTAN ROSHAN 349 AFGHANISTAN SALAAM 1616 AFGHANISTAN WASEL 1219 ALBANIA AMC 110 ALBANIA Eagle Mobile 601 ALBANIA PLUS COMMUNICATION 935 ALBANIA TELEKOM.AL 1641 ALBANIA VODAFONE 373 ALGERIA DJEZZY 208 ALGERIA MOBILIS 183 ALGERIA OOREDOO 427 AMERICAN SAMOA BLUESKY 1620 ANDORRA MOBILAND 389 ANGOLA MOVICEL 1398 ANGOLA UNITEL 176 ANGUILLA FLOW 1871 ANGUILLA LIME 1448 ANGUILLA WEBLINKS LIMITED 830 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA APUA 341 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA ATT WIRELESS 1265 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA DIGICEL 730 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA FLOW 1855 ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA LIME 547 ARGENTINA 20 607 ARGENTINA CLARO 452 ARGENTINA GLOBALSTAR 1414 ARGENTINA MOVISTAR 449 ARGENTINA NEXTEL 296 ARGENTINA PERSONAL 485 ARGENTINA PORT-HABLE 1320 ARMENIA BEELINE 232 ARMENIA KARABAKH TELECOM 983 ARMENIA ORANGE 1084 ARMENIA UCOM 1863 ARMENIA VIVACELL-MTS 237 ARUBA DIGICEL 946 ARUBA SETAR 548 AUSTRALIA 3 907 AUSTRALIA 3GIS 1117 AUSTRALIA AAPT 1061 AUSTRALIA ADVANCE COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES PTY LTD 1582 AUSTRALIA ADVANCE COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGIES PTY. LTD. 1822 AUSTRALIA AIRNET 1091 AUSTRALIA AUSGRID CORPORATION 1188 AUSTRALIA BHP BILLITON 703 AUSTRALIA CHALLENGE NETWORKS PTY. LTD. 677 AUSTRALIA CITIC PACIFIC MINING 1856 AUSTRALIA CLX NETWORKS PTY LTD 1872 AUSTRALIA COMMTEL NETWORK SOLUTIONS PTY LTD 1862 Pagina 1 Foglio1 AUSTRALIA COMPATEL LIMITED 1085 AUSTRALIA CRAZY JOHN'S 558 AUSTRALIA DEPARTMENT OF DEFENCE 728 AUSTRALIA DIALOGUE COMMUNICATIONS PTY. LTD. 1468 AUSTRALIA iiNet 611