Say "Cheese." Uncle Sam Wants Your Photograph and Fingerprints Or

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

30Th ANNIVERSARY 30Th ANNIVERSARY

July 2019 No.113 COMICS’ BRONZE AGE AND BEYOND! $8.95 ™ Movie 30th ANNIVERSARY ISSUE 7 with special guests MICHAEL USLAN • 7 7 3 SAM HAMM • BILLY DEE WILLIAMS 0 0 8 5 6 1989: DC Comics’ Year of the Bat • DENNY O’NEIL & JERRY ORDWAY’s Batman Adaptation • 2 8 MINDY NEWELL’s Catwoman • GRANT MORRISON & DAVE McKEAN’s Arkham Asylum • 1 Batman TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. JOEY CAVALIERI & JOE STATON’S Huntress • MAX ALLAN COLLINS’ Batman Newspaper Strip Volume 1, Number 113 July 2019 EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Comics’ Bronze Age and Beyond! Michael Eury TM PUBLISHER John Morrow DESIGNER Rich Fowlks COVER ARTIST José Luis García-López COVER COLORIST Glenn Whitmore COVER DESIGNER Michael Kronenberg PROOFREADER Rob Smentek IN MEMORIAM: Norm Breyfogle . 2 SPECIAL THANKS BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury . 3 Karen Berger Arthur Nowrot Keith Birdsong Dennis O’Neil OFF MY CHEST: Guest column by Michael Uslan . 4 Brian Bolland Jerry Ordway It’s the 40th anniversary of the Batman movie that’s turning 30?? Dr. Uslan explains Marc Buxton Jon Pinto Greg Carpenter Janina Scarlet INTERVIEW: Michael Uslan, The Boy Who Loved Batman . 6 Dewey Cassell Jim Starlin A look back at Batman’s path to a multiplex near you Michał Chudolinski Joe Staton Max Allan Collins Joe Stuber INTERVIEW: Sam Hamm, The Man Who Made Bruce Wayne Sane . 11 DC Comics John Trumbull A candid conversation with the Batman screenwriter-turned-comic scribe Kevin Dooley Michael Uslan Mike Gold Warner Bros. INTERVIEW: Billy Dee Williams, The Man Who Would be Two-Face . -

Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's the Public Burning

ROBERTO MARIA DAINOTTO Myth and Carnival in Robert Coover's The Public Burning Certain situations in Coover's fictions seem to conspire with a sense of impending disaster, which we have visited upon us from day to day. We have had, in that sense, an unending sequence of apocalypses, long before Christianity began and up to the present... in a lot of contemporary fiction there's a sense of foreboding disaster which is part of the times, just like self reflexive fictions. (Coover 1983, 78) As allegory, the trope of the apocalypse—a postmodern version of the Aristotelian tragic catastrophe—stands at the center of Coover's choice of content, his method of treating his materials, and his view of writing. In his fictions, one observes desperate people caught in religious nightmares leading to terrible catastrophes, a middle-aged man whose life is sacrificed at the altar of an imaginary baseball game, beautiful women repeatedly killed in the Gothic intrigues of Gerald's Party, and other hints and omens of death and annihilation. And what about the Rosenbergs, whom the powers that be "determined to burn... in New York City's Times Square on the night of their fourteenth wedding anniversary, Thursday, June 18, 1953"(PB 3)?1 In The Public Burning, apocalypse becomes holocaust—quite literally, the Greek holokauston, a "sacrifice consumed by fire." What proves interesting from a narrative point of view is that Coover makes disaster, apocalypse and holocaust part of the materials of the fictions" of the times"—which he calls" self-reflexive fictions." But what is the relation between genocide, human annihilation, and self-reflexive fictions? How do fictions" of the times" reflect holocaust? Larry McCaffery suggests: 6 Dainotto in most of Coover's fiction there exists a tension between the process of man creating his fictions and his desire to assert that his systems have an independent existence of their own. -

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected]

Comment on the Commentary of the Day by Donald J. Boudreaux Chairman, Department of Economics George Mason University [email protected] http://www.cafehayek.com Disclaimer: The following “Letters to the Editor” were sent to the respective publications on the dates indicated. Some were printed but many were not. The original articles that are being commented on may or may not be available on the internet and may require registration or subscription to access if they are. Some of the original articles are syndicated and therefore may have appeared in other publications also. 29 August 2010 should do almost the suburbs so that more opposite of what he people can enjoy Editor, Washington advocates. McMansions situated on Examiner large grassy lots. We For example, it's beneficial should quit protecting Dear Editor: to help others. So I argue endangered species that that we are morally obliged humans don't consume as David Sirota identifies a to do more to help others, food, as protecting such benefit - namely, reduced regardless of the costs species hurts people by human impact on the (including any resulting reducing economic output. environment – and argues impacts on the And we should certainly that, therefore, people are environment). avoid Mr. Sirota's practice morally obliged to take of bicycling to work: steps to achieve that We should spend more because travel by bike benefit ("A week of living time working in factories takes far more time than with low impact on the producing furniture, cars, does travel by car, bicycle environment," Aug. 29). cell phones, and the commuters thoughtlessly – But because he ignores countless other products nay, irresponsibly! - reduce competing benefits, Mr. -

SUPERGIRLS and WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION in WARTIME COMIC BOOKS By

SUPERGIRLS AND WONDER WOMEN: FEMALE REPRESENTATION IN WARTIME COMIC BOOKS by Skyler E. Marker A Master's paper submitted to the faculty of the School of Information and Library Science of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Library Science. Chapel Hill, North Carolina May, 2017 Approved by: ________________________ Rebecca Vargha Skyler E. Marker. Supergirls and Wonder Women: Female Representation in Wartime Comics. A Master's paper for the M.S. in L.S. degree. May, 2017. 70 pages. Advisor: Rebecca Vargha This paper analyzes the representation of women in wartime era comics during World War Two (1941-1945) and Operation Iraqi Freedom (2001-2010). The questions addressed are: In what ways are women represented in WWII era comic books? What ways are they represented in Post 9/11 comic books? How are the representations similar or different? In what ways did the outside war environment influence the depiction of women in these comic books? In what ways did the comic books influence the women in the war outside the comic pages? This research will closely examine two vital periods in the publications of comic books. The World War II era includes the genesis and development to the first war-themed comics. In addition many classic comic characters were introduced during this time period. In the post-9/11 and Operation Iraqi Freedom time period war-themed comics reemerged as the dominant format of comics. Headings: women in popular culture-- United States-- History-- 20th Century Superhero comic books, strips, etc.-- History and criticism World War, 1939-1945-- Women-- United States Iraq war (2003-2011)-- Women-- United States 1 I. -

Heroes and Superheroes V1.Indb

MASTER LIST OF CONTENTS Volume 1 Contents ...................................................................... v Concrete .................................................................. 187 Publisher’s Note .........................................................xi Cosmic Odyssey ...................................................... 192 Introduction ..............................................................xiii Criminal .................................................................. 197 Contributors ............................................................xvii Crisis on Infinite Earths .......................................... 202 100% ........................................................................... 1 Daredevil ................................................................. 207 100 Bullets .................................................................. 5 Daredevil: Born Again ............................................ 213 Alias .......................................................................... 10 Daredevil: The Man Without Fear .......................... 217 All-Star Batman and Robin, the Boy Wonder ........... 15 Death of Captain America, The .............................. 221 All-Star Superman ..................................................... 20 Death of Captain Marvel, The ................................ 226 Amazing Adventures of the Escapist, The ................. 25 Death: The High Cost of Living .............................. 229 American Flagg! ...................................................... -

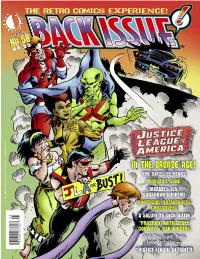

With Gerry Conway & Dan Jurgens

Justice League of America TM & © DC Comics. All Rights Reserved. 0 7 No.58 August 2012 $ 8 . 9 5 1 82658 27762 8 THE RETRO COMICS EXPERIENCE! IN THE BRONZE AGE! “JUSTICE LEAGUE DETROIT”! UNOFFICIAL JLA/AVENGERS CONWAY & DAN JURGENS A SALUTE TO DICK DILLIN “PRO2PRO” WITH GERRY THE SATELLITE YEARS SQUADRON SUPREME And the team fans love to hate — INJUSTICE GANG MARVEL’s JLA, CROSSOVERS ® The Retro Comics Experience! Volume 1, Number 58 August 2012 Celebrating the Best Comics of the '70s, '80s, '90s, and Beyond! EDITOR Michael “Superman”Eury PUBLISHER John “T.O.” Morrow GUEST DESIGNER Michael “Batman” Kronenberg COVER ARTIST ISSUE! Luke McDonnell and Bill Wray COVER COLORIST BACK SEAT DRIVER: Editorial by Michael Eury.........................................................2 Glenn “Green Lantern” Whitmore PROOFREADER Whoever was stuck on Monitor Duty FLASHBACK: 22,300 Miles Above the Earth .............................................................3 A look back at the JLA’s “Satellite Years,” with an all-star squadron of creators SPECIAL THANKS Jerry Boyd Rob Kelly Michael Browning Elliot S! Maggin GREATEST STORIES NEVER TOLD: Unofficial JLA/Avengers Crossovers................29 Rich Buckler Luke McDonnell Never heard of these? Most folks haven’t, even though you might’ve read the stories… Russ Burlingame Brad Meltzer Snapper Carr Mike’s Amazing Dewey Cassell World of DC INTERVIEW: More Than Marvel’s JLA: Squadron Supreme....................................33 ComicBook.com Comics SS editor Ralph Macchio discusses Mark Gruenwald’s dictatorial do-gooders Gerry Conway Eric Nolen- DC Comics Weathington J. M. DeMatteis Martin Pasko BRING ON THE BAD GUYS: The Injustice Gang.....................................................43 Rich Fowlks Chuck Patton These baddies banded together in the Bronze Age to bedevil the League Mike Friedrich Shannon E. -

Mardi Gras Costume Shop

Mardi Gras Costume Shop Costume Idea List The following is a list of ideas, characters, famous people, couples, and groups to help you choose your costume fantasy. We have several thousand costumes and accessories available for both rental and retail. If you don’t see what you’re looking for listed, please call us. More than likely we have it in stock, or can get it for you. Copyrighted characters are not available for rental. Where we have listed specific names, it is merely to give you a visual concept of the style of the costume. We do not rent costumes that infringe upon copyrights, and the customer is not allowed to use costumes as specific copyrighted characters. While this may seem harsh, it is done to protect the integrity and image of the character, which in many cases has taken years to build. Abba Bees Cavalier and Court Lady Abraham Lincoln Beetlejuice Cavalry Ace of Spades Belle Cave People Addams Family Bellhop Charlie Brown Ahab Belly Dancer Charlie Chaplin Al Capone and Gun Moll Benjamin Franklin Charlie's Angels Aladdin Betsy Ross Cheerleaders (Male & Female) Alex-Clockwork Orange Betty Boop Chef Ali Baba Biblical Characters Cher Alice in Wonderland Biker Chewbacca Aliens Birds Chicago Amadeus and Wife Black Widow (Avengers) Chicken Amelia Earhart Blondie Chorus Line Anastasia Blue Cookie Eating Monster Christine-Phantom of the Opera Andrew Sisters (WWII uniforms) Blues Brothers Cigarette Girls Angel and Devil Bluto Cinderella & Prince Charming Animals (We Have the Whole Zoo) Bob Marley Cindy Lauper Anna (Hoop Gown)-King -

2012 Fei World Jumping Challenge

2012 FEI WORLD JUMPING CHALLENGE COMBINED RESULTS OVERALL CATEGORY A Competition 1 Competition 2 Place Rider Horse NF Points Time 1 st Rnd 2 nd Rnd 2 nd Rnd 1 st Rnd 2 nd Rnd 2 nd Rnd 1 Bader Mohammed Alfard Tallista V KSA 0 0 47.70 0 0 43.30 0 91.00 2 Bandar Sami Binmahfouz Lincoln KSA 0 0 47.74 0 0 44.41 0 92.15 3 Victoria Gimenez Monarca II ARG 0 0 48.35 0 0 46.64 0 94.99 4 Santiago Diaz Ortega Tizimin COL 0 0 49.40 0 0 46.17 0 95.57 5 Julio Cesar Romero Cristancho Micholi COL 0 0 51.77 0 0 44.70 0 96.47 6Majid Sharifi franlaren Belle Amore IRI 0 0 46.85 0 0 51.04 0 97.89 7 Gustavo Machado Norfolk Du Findez VEN 0 0 55.36 0 0 45.13 0 100.49 8 Rebekah Van Tiel Adeaze NZL 0 0 49.80 0 0 51.60 0 101.40 9 Bernardo Amaya Acosta Adeaze COL 0 0 53.81 0 0 48.05 0 101.86 10 Shannon Smith Zadkine RSA 0 0 53.34 0 0 48.99 0 102.33 11 Carlos Jose Cola Ferres Aurelio ECU 0 0 53.66 0 0 48.97 0 102.63 12 Roberto Gonzalez Tempranillo* GUA 0 0 55.15 0 0 47.83 0 102.98 13 Ebrahim Moghadasi Senator IRI 0 0 50.51 0 0 52.66 0 103.17 14 Cailin Fensham Cayenne RSA 0 0 54.18 0 0 49.06 0 103.24 15 Mandy Johnstone Callaho Satine RSA 0 0 52.77 0 0 50.57 0 103.34 16 Michelle Zwonnikoff Ulana RSA 0 0 53.31 0 0 50.05 0 103.36 17 Carlota Bonnet Warda VEN 0 0 57.98 0 0 46.05 0 104.03 18 Michelle Navarro Grau Michelle Navarro Grau PER 0 0 54.33 0 0 49.78 0 104.11 19 Kyla Bruyns The Madji RSA 0 0 51.74 0 0 53.14 0 104.88 20 Janine Khoo Château du Lys SIN 0 0 56.34 0 0 48.62 0 104.96 21 Oscar Franzius G&C Quest Z VEN 0 0 53.57 0 0 51.46 0 105.03 22 Carlos Quiñones Carlos -

Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” the Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2010 Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, Mad Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/2330 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books Nathan Vernon Madison Copyright © 2010 Nathan Vernon Madison Isolationism, Internationalism and the “Other:” The Yellow Peril, German Brute and Red Menace in Early to Mid Twentieth Century Pulp Magazines and Comic Books A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of History at Virginia Commonwealth University by Nathan Vernon Madison Master of History – Virginia Commonwealth University – 2010 Bachelor of History and American Studies – University of Mary Washington – 2008 Thesis Committee Director: Dr. Emilie E. Raymond – Department of History Second Reader: Dr. John T. Kneebone – Department of History Third Reader: Ms. Cindy Jackson – Special Collections and Archives – James Branch Cabell Library Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December, 2010 i Acknowledgments There are a good number of people I owe thanks to following the completion of this project. -

Frank Spangler, Sr. Editorial Cartoons Collection

FRANK SPANGLER, SR. EDITORIAL CARTOONS COLLECTION Finding aid Call number: LPR201 Extent: 2.5 cubic ft. (6 book boxes, 1 oversize box, 1 oversize folder.) To return to the ADAHCat catalog record, click here: http://adahcat.archives.alabama.gov:81/vwebv/holdingsInfo?bibId=30072 Alabama Dept. of Archives and History, 624 Washington Ave., Montgomery, AL 36130 www.archives.alabama.gov CONTAINER LISTING Collection name: Frank Spangler, Sr. editorial cartoons collection Collection number: LPR201 World War II cartoons Some other topics may be included. Box/Folder Title/Description 1 1 #1. Looks zutty – on Mediterranean Street, Hitler and Mussolini attacked by winds of U. S. and British air force 1 1 #2. Time to wake up! – USA Salvage Drive, war bonds 1 1 #3. To make a happy day – Three men in an “Axis” tub, Hitler, Mussolini, and Hirohito 1 1 #4. Time Flows On – synthetic rubber program 1 1 #5. The trail – Hirohito sells stolen car tire 1 1 #6. Souvenirs, and the price – soldier leaves Dieppe with Nazi souvenirs 1 1 #7. Forward and backward – ocean scene with Uncle Sam, United Nations, Mahatma Gandhi and Jap advance 1 1 #8. A tug of war – Russia with “long war ostrich” and “short war” pig 1 1 #9. Keep on stamping – Recycling on home front 1 1 #10. Let the punishment fit the crimes – Home front, black outs, income tax, and gardening 1 1 #11. A run down sinking feeling – ocean scene: Uncle Sam on battle ship, Hitler in submarine, Hirohito in canoe 1 1 #12. The toll bridge – Hitler prevents supplies from reaching Britain 1 1 #13. -

Batman/Superman Vol. 6 Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BATMAN/SUPERMAN VOL. 6 PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Peter J. Tomasi | 224 pages | 11 Apr 2017 | DC Comics | 9781401268190 | English | United States Batman/Superman Vol. 6 PDF Book April 21, Joshua Williamson , Rafa Sandoval. Joe: America's Elite among others. All told, I'd round the overall quality of this collection to 3 stars. Add to Wish List. Then Joe Casey phones in a story about a Durlan who comes to earth to wipe out the last Kryptonian. Batman and Superman are raised to be dictators of the world, eliminating all opposition and killing people who would otherwise be their friends. President Lex Luthor declares Superman and Batman enemies of the state, claiming that a Kryptonite asteroid headed for Earth is connected to an evil plot by Superman. Enlarge cover. The art was nice as well. Tweet Clean. While I could tell they were running out of ideas, the comics were still fun, especially the one-or-two-page stories at the end. Until you earn points all your submissions need to be vetted by other Comic Vine users. Darkseid makes a deal with them in one reality to send them back through time to stop the supervillains who raised them from altering history. World Finest. Books by Joe Casey. Frank Tieri actually writes a winning story here. Matt rated it liked it Jun 05, Darkseid kidnaps Kara, intending her to be the new leader of the Female Furies. It was a dumb ending to a dumbed down reboot of one of the greatest graphic novel series of all time. Joshua Williamson wrote "Fright Night" issue Jan 18, Ben Truong rated it liked it Shelves: comics , superheroes , trade- paperback. -

The Jewish Comic Book Industry, 1933-1954

“THE WHOLE FURSHLUGGINER OPERATION”: THE JEWISH COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY, 1933-1954 By Sebastian T. Mercier A DISSERTATION Submitted to Michigan State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of History – Doctor of Philosophy 2018 ABSTRACT “THE WHOLE FURSHLUGGINER OPERATION”: THE JEWISH COMIC BOOK INDUSTRY, 1933-1954 By Sebastian T. Mercier Over the course of the twentieth century, the comic book industry evolved from an amateur operation into a major institution of American popular culture. Comic books, once considered mere cultural ephemera or quite simply “junk,” became a major commodity business. The comic book industry emerged out of the pulp magazine industry. According to industry circulation data, new comic book releases increased from 22 in 1939 to 1125 titles by the end of 1945. Comic book scholars have yet to adequately explain the roots of this historical phenomenon, particularly its distinctly Jewish composition. Between the years of 1933 and 1954, the comic book industry operated as a successful distinct Jewish industry. The comic book industry emerged from the pulp magazine trade. Economic necessity, more than any other factor, attracted Jewish writers and artists to the nascent industry. Jewish publishers adopted many of the same business practices they inherited from the pulps. As second-generation Jews, these young men shared similar experiences growing up in New York City. Other creative industries actively practiced anti-Semitic hiring procedures. Many Jewish artists came to comic book work with very little professional experience in cartooning and scripting. The comic book industry allowed one to learn on the job. The cultural world comic books emerged out of was crucially important to the industry’s development.