Urban Elements Advanced Studies in Urban Design

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Implementing Road and Congestion Pricing- Lessons from Singapore

European Conference of Ministers of Transport Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport Japanese Government 2-3 March 2005 Akasaka Prince Hotel, Tokyo IImmpplleemmeennttiinngg RRooaadd aanndd CCoonnggeessttiioonn PPrriicciinngg-- LLeessssoonnss ffrroomm SSiinnggaappoorree Jeremy YAP Ministry of Transport Singapore Name : Jeremy Yap Evan Gwee Title : Deputy Director, Assistant Manager, Land Transport Division, Planning Department, Ministry of Transport, Land Transport Authority, Singapore Singapore Address : 460 Alexandra Road, #39-00 460 Alexandra Road, #24-00 Singapore 119963 Singapore 119963 Tel : +65-63752534 +65-63757612 Fax : +65-62768081 +65-63757213 e-mail : [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Singapore has enjoyed rapid economic growth and intensive urbanisation over the last few decades and this has translated into an increase in travel demand. To support the increased travel demand, the Singapore government has over the years planned and put many measures in place to ensure that our transport system is adequate, sustainable and relevant. Our overall land transport strategy hinges on four key areas namely integrating land use / transport planning, providing a quality public transport system, developing a comprehensive road network and maximising its capacity and managing demand of road usage through ownership and usage measures. Our transport philosophy is to maintain a proper balance between the use of private and public transport and increases the efficiency of traffic flow on our roads. While most cities adopt the first three components, Singapore is one of the very few cities to have pursued travel demand management for the past 30 years and with a degree of success, as is evidenced by the respectable speeds along the city roads and expressways. -

Bto) Flats in May 2015 Exercise

ANNEX A1 INFORMATION ON BUILD-TO-ORDER (BTO) FLATS IN MAY 2015 EXERCISE CLEMENTI CREST Clementi Crest is located along Clementi Avenue 3 at the Clementi Town Centre. It has 385 flats comprising 229 units of 4-room and 156 units of 5-room flats. A childcare centre will be provided in this development. 2 Residents of Clementi Crest will be served by the Clementi MRT station and numerous public bus services at the Clementi bus interchange. They will be served by a wide range of facilities in the Clementi Town Centre such as Clementi Mall, a polyclinic as well as many retail shops and eating places. For leisure and recreation, the residents can visit the Clementi Community Centre, Clementi Sports Hall, Clementi Swimming Complex, Clementi Stadium, etc. 3 The schools within Clementi include Clementi Primary School, Pei Tong Primary School, Nan Hua Primary School, Nan Hua High School, Singapore Polytechnic and National University of Singapore. The Ayer Rajah Expressway (AYE) is a short drive away providing connectivity to the rest of Singapore. 1 2 EASTLINK I @ CANBERRA and EASTLINK II @ CANBERRA 4 Two BTO projects in Sembawang Town are offered for sale. EastLink I @ Canberra and EastLink II @ Canberra are located along Canberra Link and across the road from the upcoming Canberra MRT station. Both projects are located near Sungei Simpang Kiri. The details are set out in Table A1(1). Table A1(1): EastLink I @ Canberra and EastLink II @ Canberra No. of Units Project Facilities 2-room 3-room 4-room Total EastLink I @ Canberra 229 139 232 600 Neighbourhood Centre (NC) comprising supermarket, food court, restaurants/ F&B kiosks, shops and enrichment centres. -

Preliminary Pricing Supplement

IMPORTANT NOTICE NOT FOR DISTRIBUTION IN THE UNITED STATES OR TO U.S. PERSONS IMPORTANT: You must read the following disclaimer before continuing. The following disclaimer applies to the attached preliminary pricing supplement. You are advised to read this disclaimer carefully before accessing, reading or making any other use of the attached preliminary pricing supplement. In accessing the attached preliminary pricing supplement, you agree to be bound by the following terms and conditions, including any modifications to them from time to time, each time you receive any information from us as a result of such access. Confirmation of Your Representation: In order to be eligible to view the attached preliminary pricing supplement or make an investment decision with respect to the securities, investors must not be a U.S. person (within the meaning of Regulation S under the Securities Act (as defined below)). The attached preliminary pricing supplement is being sent at your request and by accepting the e-mail and accessing the attached preliminary pricing supplement, you shall be deemed to have represented to us (1) that you are not resident in the United States (“U.S.”) nor a U.S. person, as defined in Regulation S under the U.S. Securities Act of 1933, as amended (the “Securities Act”) nor are you acting on behalf of a U.S. person, the electronic mail address that you gave us and to which this email has been delivered is not located in the U.S. and, to the extent you purchase the securities described in the attached preliminary pricing supplement, you will be doing so pursuant to Regulation S under the Securities Act, and (2) that you consent to delivery of the attached preliminary pricing supplement and any amendments or supplements thereto by electronic transmission. -

198 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

198 bus time schedule & line map 198 Boon Lay Int View In Website Mode The 198 bus line (Boon Lay Int) has 2 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Boon Lay Int: 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM (2) Bt Merah Int: 5:30 AM - 11:44 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 198 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 198 bus arriving. Direction: Boon Lay Int 198 bus Time Schedule 44 stops Boon Lay Int Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM Monday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM Bt Merah Ctrl - Bt Merah Int (10009) 3591 Bukit Merah Central, Singapore Tuesday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM Bt Merah Ctrl - Blk 1003 (10659) Wednesday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM 1003 Jalan Bukit Merah, Singapore Thursday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM Jln Bt Merah - Opp Bt Merah Sec Sch (10101) Friday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM Jln Bt Merah - Opp Blk 28 (10111) Saturday 5:30 AM - 11:33 PM 16 Jalan Kilang, Singapore Jln Bt Merah - Opp Blk 2 (10131) 4545 Jalan Bukit Merah, Singapore 198 bus Info Queensway - Aft Queenstown Npc Hq (11021) Direction: Boon Lay Int Stops: 44 Queensway - Opp Queen's Cl (11031) Trip Duration: 77 min Line Summary: Bt Merah Ctrl - Bt Merah Int (10009), Queensway - Aft C'Wealth Dr (11041) Bt Merah Ctrl - Blk 1003 (10659), Jln Bt Merah - Opp Queensway, Singapore Bt Merah Sec Sch (10101), Jln Bt Merah - Opp Blk 28 (10111), Jln Bt Merah - Opp Blk 2 (10131), Queensway - Opp Queenstown Polyclinic (11051) Queensway - Aft Queenstown Npc Hq (11021), 300 Tanglin Halt Road, Singapore Queensway - Opp Queen's Cl (11031), Queensway - Aft C'Wealth Dr (11041), Queensway -

Annex B Plans for Jurong Lake District and Beyond Potential for New

Annex B Plans for Jurong Lake District and Beyond Potential for new quality homes The stretch of the Ayer Rajah Expressway (AYE) from Yuan Ching Road to Jurong Town Hall Road could be realigned to free up land south of Jurong Lake for residential development, and to integrate the Pandan Reservoir area with the district to form a larger and more cohesive development area. Environmental improvements can be made to the surrounding parks and waterbodies such as Jurong River, Pandan River, Pandan Reservoir and Teban Gardens to create an attractive waterfront residential district amidst lush greenery for Singaporeans to enjoy. Better accessibility and connectivity Besides the East-West and North-South MRT lines which are undergoing upgrading, the new Jurong Regional and Cross-Island MRT lines, a new integrated transport hub at Jurong East, agencies will explore building more dedicated cycling paths and park connectors. These will strengthen connectivity and accessibility between Jurong Lake District and the surrounding residential and business nodes such as Pandan and Teban gardens estates, Tengah New Town, JTC’s proposed integrated R&D and industrial township centred around Clean Tech Park, NTU, and Bulim and Tengah industrial estates. This will reduce the need to drive in the western region and promote a healthier lifestyle. Possible location for High-Speed Rail terminus The Government is currently studying where the future Kuala Lumpur- Singapore High-Speed Rail (HSR) terminus could be sited in Singapore. Jurong East is one of the possible locations. If it is eventually sited in Jurong East, Jurong Lake District will become a gateway to Singapore and potentially our second Central Business District. -

Land Transport Masterplan

LAND TRANSPORT MASTERPLAN MP-endpaperproposal.indd 8-9 2/18/08 6:18:47 PM For Singapore to realise its aspirations to be a thriving global city, its transport infrastructure is critical. Over the next 10 to 15 years, the transport system must support economic growth, a bigger population, higher expectations and more diverse lifestyles. With this in mind, we embarked on a comprehensive Land Transport Review in October 2006. We solicited and benefited from contributions from a broad spectrum of people including students, workers, employers, commuters, transport operators, ordinary Singaporeans and experts; at home and abroad. In total, more than 4,500 people contributed their time, energies and ideas to this review. The culmination of this effort is a Land Transport Masterplan that strives to make Singapore a great city to live, work and play in. This calls for major MINISTER’S changes to vastly improve our land transport system. It is a plan to build and develop a more people-centred transport system that is technologically intelligent, yet engagingly human. FOREWORD Singaporeans can look forward to a more integrated and user-friendly public transport system. Fast and reliable bus services will complement a greatly expanded rail network to bring people where they want to go quickly. Tree-lined sheltered walkways in the heartlands and bustling underground walkways filled with shops in the city will ensure a pleasant walk to bus and train stations for all commuters. Varied transport choices like premium buses, taxis and cycling will help to cater to different needs. With the construction of new expressways, island-wide connectivity will also be significantly improved. -

Preliminary Study of Transport Pattern and Demand in Singapore for Future Urban Air Mobility

This document is downloaded from DR‑NTU (https://dr.ntu.edu.sg) Nanyang Technological University, Singapore. Preliminary study of transport pattern and demand in Singapore for future urban air mobility Wai, Cho Wing; Tan, Kailun; Low, Kin Huat 2021 Wai, C. W., Tan, K. & Low, K. H. (2021). Preliminary study of transport pattern and demand in Singapore for future urban air mobility. AIAA SciTech 2021 Forum, 1‑10. https://dx.doi.org/10.2514/6.2021‑1633 https://hdl.handle.net/10356/147431 https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2021‑1633 © 2021 Nanyang Technological University. Published by the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics, Inc., with permission. Downloaded on 25 Sep 2021 21:31:32 SGT Preliminary Study of Transport Pattern and Demand in Singapore for Future Urban Air Mobility Cho Wing Wai1 School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639798 Kailun Tan2 Air Traffic Management Research Institute, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 637460 Kin Huat Low3 School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore 639798 This paper aims to present the preliminary feasibility study of future urban air mobility (UAM), by means of flying taxis, based on the existing transportation demands in Singapore. Some cities such as Dallas, Los Angeles and Melbourne have already investigated the trends of urban air mobility and planned to launch its eVTOL in 2023. The consideration behind flying taxis in Singapore serves to smoothen traffic congestions in the central and industrial areas due to occasional traffic jams caused by road works or accidents, providing greater transportation convenience in a cosmopolitan city. -

List of Locations Where No Installation of Banners Is Allowed.Xlsx

List of locations where no installation of banners is allowed (Please note that the list is non-exhaustive) S/No. Locations 1 Adam Flyover near Dunearn Close LP49F 2 Adam Flyover near Jln Kembang Melati LP69F 3 Adam Rd aft Adam Park LP34/9 4 Adam Rd bf Adam Dr (exit PIE Changi) LP16 5 Adam Rd bf Sime Rd LP6 6 Adam Rd near Japanese Association LP35 7 Adam Road approaching Dunearn Road LP 37/2 8 Airport Road approaching Eunos Link LP 63 9 Alexandra Rd (Near Malan Rd) LP179 10 Alexandra Rd (Near NOL Building) LP200 11 Alexandra Rd / Depot Rd LP162 12 Alexandra Rd approaching Commonwealth Ave/Leng Kee Bf LP69 13 Alexandra Rd bef Dawson Rd (Centre Median) SP opp LP84 14 Alexandra Rd bet Malan Rd and Hyderabad Rd LP 186 15 Alexandra Rd opp Anchorpoint Shopping Centre LP112-1 16 Alexandra Rd opp Blk101 Henderson Cresent LP21 17 Alexandra Rd opp Cycle & Carriage SP 18 Alexandra Rd opp Pat's School House LP32 19 Alexandra Rd opp Queensway Shopping Centre LP128 20 Alexandra Rd opp Volvo LP77 21 Alexandra Rd/Tanglin Rd/Tiong Bahru Rd (Centre Median) TL8 22 Alexandra Road approaching Pasir Panjang Road / Telok Blangah Road LP 187 23 Aljunied Rd between Sims Ave and Sims Dr LP 8 24 AMK Ave 1 (After AMK St 32) SP 25 AMK Ave 1 (After Marymount Rd) LP70 26 AMK Ave 1 (Outside SPC Petrol Station) LP93 27 AMK Ave 1 / AMK Ave 10 Junction LP136 28 AMK Ave 1 / AMK Ave 2 TL2 29 AMK Ave 1 / AMK Ave 3 TL7 30 AMK Ave 3 / AMK Ave 10 TL5 31 AMK Ave 3 / AMK Ave 4 TL6 32 AMK Ave 3 / AMK St 11 LP17 33 AMK Ave 3 / AMK St 12 TL1 34 AMK Ave 3 / AMK St 42 TL7 35 AMK Ave -

List of Major Arterial Road Corridors with EMAS and Strategic Importance of Each Corridor

List of Major Arterial Road Corridors with EMAS and Strategic Importance of Each Corridor List of Major Arterial Roads with EMAS Effective Corridor Estimated Strategic Timeline Distance (km) Importance May 2011 Woodlands Road–Upper Bukit Timah Road– 18 Alternative to Bukit Timah Road–Dunearn Road (Northern) BKE & PIE May 2011 * West Coast Highway (between Keppel 7.3 Serves ports Road/Shenton Way and Pasir Panjang Alternative to Road/South Buona Vista Road) [Western] AYE/ECP May 2012 Serangoon Road–Upper Serangoon Road 12 Links PIE and (Northern) TPE Alternative to CTE and KPE May 2012 Thomson Road–Upper Thomson Road 10.4 Links PIE and (Northern) SLE Alternative to CTE May 2012 Portsdown Avenue–Still Road South (Outer Ring 21 Major bypass Road) Links AYE, PIE, CTE, KPE and ECP May 2012 Orchard Road–Bras Basah Road (Central) 3.1 Links to Marina Centre Major shopping destination May 2012 Nicoll Highway–Shenton Way (Central) 5.7 Links KPE Alternative to ECP May 2014 * West Coast Highway–Jalan Buroh–Pioneer 17.7 Alternative to Road (between Pasir Panjang Road/South Buona AYE Vista Road and Pioneer Road/Tuas West Road) [Western] November 2014 Upper Jurong Road–Boon Lay Way– 16.7 Alternative to Commonwealth Avenue West–Commonwealth AYE & PIE Avenue (Western) November 2014 Geylang Road–Changi Road– Sims Avenue– 16.2 Alternative to Sims Avenue East–New Upper Changi Road– PIE Upper Changi Road East (Eastern) Links to TPE November 2014 Mounbatten Road–East Coast Road–Upper East 13.4 Alternative to Coast Road–Bedok Road–Xilin Avenue (Eastern) PIE & ECP Total 141.5 AYE – Ayer Rajah Expressway, BKE – Bukit Timah Expressway, CTE – Central Expressway, ECP – East Coast Parkway, KPE – Kallang-Paya Lebar Expressway, PIE – Pan Island Expressway, SLE – Seletar Expressway, TPE - Tampines Expressway *Note: West Coast Highway corridor was implemented in 2 stages in 2011 and 2014. -

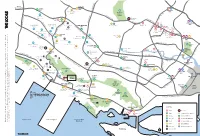

Map for Lightbox

D A O R HOLLAND R To Jurong East E VILLAGE R DOVER R MRT A MRT F NEWTON Holland Village Singapore MRT Market D Botanic A H O OL Gardens R Y L S A T D Singapore A N D T A W R Polytechnic O Gleneagles O O S O A R C R The Star N D C Hospital H S I E A T R D Vista E D O N U N R V BUONA VISTA A O E A E Q PI D D R ER ROA Tang M MRT LITTLE INDIA E R L O D Plaza Anglo-Chinese A D MRT C C United World A O The Metropolis COMMONWEALTH Tanglin Mall A D Junior College R O Dempsey Hill ORCHARD College TA M O The S M MRT R I O MRT The locale V N N Paragon The A O Biopolis W S N E R Centrepoint A E O L T T ION Takashimaya Anglo-Chinese School U H A B A P V Orchard (Independent) Fairfield H E T N Mandarin R one-north U SOMERSET is E Methodist O Gallery N MRT Phoenix MRT School AD 313 Singapore Institute New Town Queensway Park GRANGE RO Primary School Secondary School @Somerset of Technology INSEAD Asia DHOBY GHAUT MRT Fusionopoliis D A O VER Timbre+ RI VALLEY Fort R ROA Tanglin Trust School MDIS Campus D Canning National University N I of Singapore National QUEENSTOWN L Park G University MRT N Wessex A T FORT Hospital Cresent Girls’ Valley K T IM CANNING E School Point E Global Indian Great World S R Q ALE MRT T KENT RIDGE XANDRA E U ROA N S E International D Alexandra Canal City P G A ASIR MRT E I PA N School R R NJ S AN W O O G GANGES AVEN A T R A UE OA Science Park II - Y D IC D AYER RAJAH EXPRESSWAY (AYE) REDHILL Quayside V Business Spaces Science Park I Anchorpoint MRT Singapore River D Tiong Bahru A O O IKEA HA K R AD O Plaza U VELOC R Alexandra T R CLARKE QUAY A West Coast Park A T L ABC M MRT E TIONG BAHRU Brickworks D R Singapore Alexandra MRT O R Science Park II Hospital Gan Eng Seng E TIONG BAHRU ROAD A D Pasir Panjang Kent Ridge Park Primary School W Tiong Bahru JALA O Wholesale Centre Haw Par Villa N BU L Market KIT M ERA CHINATOWN H TE) HAW PAR VILLA Buona South Y (C WA MRT MRT Primary School SS RE Southern XP terfront city. -

Infrastructure Projects

INFRASTRUCTURE Marina Coastal Expressway The Marina Coastal Expressway is a dual 5-lane, 5 km long expressway joining the Kallang-Paya Lebar Expressway and the East Coast Parkway in the east to the Ayer Rajah Expressway in the west. Contract 481 at Marina Wharf is a 0.95km stretch connecting to the Ayer Rajah Expressway. It comprises of the design and construction of 490m of dual carriageway at-grade piled road system, 460m of dual carriageway viaduct structure linking to South Quay Viaduct and slip road connections to Maxwell Road and from Maxwell Road to Sheares Avenue. For the construction of the project, there was 8.9 hectares of land reclamation at Marina Wharf and the construction of trunk sewers. Client: Land Transport Authority Project Value: S$305M ECAS’ Role: Qualified Person Supervision Completion Date: 2013 Alexandra Arch and Jurong East Street 21 Infrastructure Works at Forest Walk Lorong Halus Alexandra Arch is an 80 meter The project consists of the widening of The proposed 45.4m road is a dual pedestrian bridge linking Hilltop Walk Jurong East Street 21 and a new road 4-lane, approximately 800m long and Forest Walk. It is designed as an between Boon Lay Way and Jurong which will have an intersection with open leaf across the road. The arch was Gateway Road including the design and existing Tampines Road with proper awarded with the Singapore Structural construction of a pedestrian overhead traffic arrangements. The road will Steel Society award for Distinguished bridge with pre-cast prestressed cross the existing Sungei Serangoon use of Structural Steel for its Creativity, girders, reinforced concrete pier, pier Canal, which is to be provided with Value, and Innovation. -

A Forward Force

A Forward Force Annual Report 2021 ABOUT AIMS APAC REIT (“AA REIT”) is a real estate investment trust listed on the AIMS APAC REIT Mainboard of the Singapore Exchange Securities Trading Limited (“SGX-ST”) since 2007. The principal investment objective of AA REIT is to invest in a diversified portfolio of income-producing industrial, logistics and business park real estate located throughout the Asia Pacific region. The real estate assets are utilised for a variety of purposes, including but not limited to warehousing & distribution activities, business parks activities and manufacturing activities. AA REIT’s portfolio consists of 28 properties, of which 26 properties are located throughout Singapore, and 2 in Australia. VISION MISSION To be the preferred Asia To provide investors with sustainable Pacific industrial, logistics long-term returns through strategic and business park real acquisitions and partnerships, prudent estate solutions provider to capital management and proactive asset our tenants and partners. management of a high quality industrial, logistics and business park real estate portfolio throughout Asia Pacific. On the Cover Breathtaking waterfalls are carved through nature’s rhythmic motion over geological timescales. They showcase how environmental elements can be forceful yet gentle, gradual yet radical, resilient yet flexible. It is a persistent progression, a continuous flow of energy and life. In similar fashion, our growth is a result of our unwavering dedication to seek constant progress. A strong flow of balanced