Nation, Football, and Critical Discourse Analysis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Helsinki Olympic Stadium - Helsinki Saturday 11 October 2014 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Finland Group F - Matchday -11 Greece Last updated 12/07/2021 16:57CET Official Partners of UEFA EURO 2020 Previous meetings 2 Match background 4 Squad list 5 Head coach 7 Match officials 8 Competition facts 9 Match-by-match lineups 10 Team facts 12 Legend 14 1 Finland - Greece Saturday 11 October 2014 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Helsinki Olympic Stadium, Helsinki Previous meetings Head to Head FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Forssell 14, 45, Riihilahti 21, Kolkka 05/09/2001 QR (GS) Finland - Greece 5-1 Helsinki 38, Litmanen 53; Karagounis 30 07/10/2000 QR (GS) Greece - Finland 1-0 Athens Liberopoulos 59 EURO '96 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Litmanen 44, Hjelm 11/06/1995 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 2-1 Helsinki 54; Nikolaidis 6 Markos 22, Batista 69, 12/10/1994 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 4-0 Salonika Machlas 76, 89 EURO '92 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Saravakos 49, 30/10/1991 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 2-0 Athens Borbokis 51 Ukkonen 50; 09/10/1991 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 1-1 Helsinki Tsalouchidis 74 1980 UEFA European Championship Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached Nikoloudis 15, 25, Delikaris 23, 47, 11/10/1978 PR (GS) Greece - Finland 8-1 Athens Mavros 38, 44, 75 (P), Galakos 81; Heiskanen 61 Ismail 35, 82, 24/05/1978 PR (GS) Finland - Greece 3-0 Helsinki Nieminen 80 1968 UEFA European Championship -

DIE ABBITTE ALEX FREI Der Schweizer Captain Ist Kein Fussballkünstler

DAS MAGAZIN ZUR FUSSBALL-WELTMEISTERSCHAFT 2010 DIE ABBITTE ALEX FREI Der Schweizer Captain ist kein Fussballkünstler. Aber er arbeitet, leidet, kämpft. Bis zur Schmerzgrenze. XAVI HERNÁNDEZ: DER SPÄTZÜNDER REINALDO RUEDA: DER VOLKSHELD VON HONDURAS eDitorial inhalt 18 12 eDitorial 28 Bu Benträume 32 Da ist Alex, den sein Vater unterschätzte. Da ist Valon, der im Asylzentrum tagelang nichts ass. Da ist Xavi, der vor einem Tortilla-Teller sass und sagte, er verlasse Barcelona nicht. Und inhalt da ist Carlitos, der in Santiago de Chile den Ball jongliert und von Barcelona träumt. Alex, Valon, Xavi und Carlitos sind Buben, 4 der captain 18 der unterSchied deren Geschichten dieses Magazin erzählt. Das Alex Frei hat eine Karriere gemacht, wie es Die Teams aus Chile und der Schweiz weisen Heft blickt voraus auf die Fussball-WM, die sie im Schweizer Fussball nicht oft gibt. Doch einige Parallelen auf. Weshalb der chilenische ab dem 11. Juni in Südafrika und damit erst- die Angst, nicht richtig wahrgenommen zu Fussball dennoch anders funktioniert, zeigt ein mals auf dem afrikanischen Kontinent statt- werden, lässt ihn bis heute nicht ganz los. Besuch in Santiago de Chile. findet. Auf der ganzen Welt ist der Fussball das Spiel der Kinder, die den Ball jagen, weil es um den Spass geht, noch nicht um Millionen. 10 daS privatarchiv 28 der Spätzünder Die Macht des Fussballs spiegelt die Kraft der Der Schweizer Nationaltrainer Ottmar Hitz- Erst seit zwei Jahren erntet der 30-jährige Xavi Kinder. Denn der Fussball brauchte die Basis feld hat eine beeindruckende Vita. In einem Hernández die Früchte seiner Hartnäckigkeit. -

Sample Download

THE HISTORYHISTORYOF FOOTBALLFOOTBALL IN MINUTES 90 (PLUS EXTRA TIME) BEN JONES AND GARETH THOMAS THE FOOTBALL HISTORY BOYS Contents Introduction . 12 1 . Nándor Hidegkuti opens the scoring at Wembley (1953) 17 2 . Dennis Viollet puts Manchester United ahead in Belgrade (1958) . 20 3 . Gaztelu help brings Basque back to life (1976) . 22 4 . Wayne Rooney scores early against Iceland (2016) . 24. 5 . Brian Deane scores the Premier League’s first goal (1992) 27 6 . The FA Cup semi-final is abandoned at Hillsborough (1989) . 30. 7 . Cristiano Ronaldo completes a full 90 (2014) . 33. 8 . Christine Sinclair opens her international account (2000) . 35 . 9 . Play is stopped in Nantes to pay tribute to Emiliano Sala (2019) . 38. 10 . Xavi sets in motion one of football’s greatest team performances (2010) . 40. 11 . Roger Hunt begins the goal-rush on Match of the Day (1964) . 42. 12 . Ted Drake makes it 3-0 to England at the Battle of Highbury (1934) . 45 13 . Trevor Brooking wins it for the underdogs (1980) . 48 14 . Alfredo Di Stéfano scores for Real Madrid in the first European Cup Final (1956) . 50. 15 . The first FA Cup Final goal (1872) . 52 . 16 . Carli Lloyd completes a World Cup Final hat-trick from the halfway line (2015) . 55 17 . The first goal scored in the Champions League (1992) . 57 . 18 . Helmut Rahn equalises for West Germany in the Miracle of Bern (1954) . 60 19 . Lucien Laurent scores the first World Cup goal (1930) . 63 . 20 . Michelle Akers opens the scoring in the first Women’s World Cup Final (1991) . -

Iz Igre Do Igre – Metodika Učenja Igre V Napadu Na Osnovi Analize Igre Reprezentance Španije – Zmagovalca Euro 2008

UNIVERZA V LJUBLJANI FAKULTETA ZA ŠPORT Športno treniranje – nogomet IZ IGRE DO IGRE – METODIKA UČENJA IGRE V NAPADU NA OSNOVI ANALIZE IGRE REPREZENTANCE ŠPANIJE – ZMAGOVALCA EURO 2008 DIPLOMSKO DELO MENTOR: doc. dr. Zdenko Verdenik, prof. šp. vzg. Avtor dela: Davor Mučić SOMENTOR: asist. dr. Marko Pocrnjič, prof. šp. vzg. RECENZENT: doc. dr. Marko Šibila, prof. šp. vzg. KONZULTANT: Iztok Kavčič, prof. šp. vzg. Ljubljana, 2010 ZAHVALA Zahvaljujem se mentorju dr. Zdenku Verdeniku za strokovno pomoč pri izdelavi diplomske naloge, kakor tudi za vse nasvete in pogovore, ki so mi odprli širši pogled na nogometnem področju. Zahvaljujem se tudi dr. Marku Pocrnjiču za vso strokovno pomoč tekom študija. Zahvaljujem se staršem, da so mi omogočili študij in Marini za podporo, razumevanje in spodbujanje. Zahvaljujem se tudi vsem ostalim sošolcem in prijateljem za pomoč in sodelovanje v času študija. Ključne besede: nogomet, analiza igre, taktika, napad, metodika, učenje IZ IGRE DO IGRE – METODIKA UČENJA IGRE V NAPADU NA OSNOVI ANALIZE IGRE REPREZENTANCE ŠPANIJE – ZMAGOVALCA EURO 2008 Davor Mučić Univerza v Ljubljani, Fakulteta za šport, 2010 Športno treniranje – nogomet 123 strani, 120 slik, 71 skic, 19 virov IZVLEČEK Diplomsko delo je sestavljeno iz treh glavnih sklopov. V prvem delu smo se posvetili teoretični vsebini. V predstavili smo sodoben model nogometne igre in njene značilnosti, nogometno igro v fazi napada, taktiko igre, kjer smo se osredotočili na skupinsko in moštveno igro v napadu, pri učnih metodah pa izpostavili situacijsko metodo in metodo igre. Posebno pozornost smo namenili trenerjevim sposobnostim učinkovitega analiziranja samega sebe, situacije in svojih varovancev, kot sistema spremenljivk, ki se nenehno spreminjajo. -

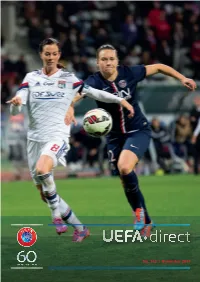

No. 143 | November 2014 in This Issue

No. 143 | November 2014 IN THIS ISSUE Official publication of the SECOND WOMEN IN FOOTBALL Union of European Football Associations LEADERSHIP SEMINAR 4 Images The second week-long Women in Football Leadership seminar Getty took place at the House of European Football in Nyon at the end via Chief editor: of October. Emmanuel Deconche UEFA Produced by: PAO graphique, CH-1110 Morges SOLIDARY PAYMENTS TO CLUBS Printing: 10 Artgraphic Cavin SA, A share of the revenue earned by the UEFA Champions League CH-1422 Grandson goes to the clubs involved in the UEFA Champions League and Editorial deadline: UEFA Europa League qualifying rounds. This season, 183 clubs Images 8 November 2014 have benefitted. Getty The views expressed in signed articles are not necessarily the official views of UEFA. HISTORIC AGREEMENT SIGNED The reproduction of articles IN BRUSSELS 13 published in UEFA·direct is authorised, provided the On 14 October the European Commission and UEFA Commission source is indicated. signed an agreement designed to reinforce relations between the two institutions. European POSITIVE FEEDBACK ON FINANCIAL FAIR PLAY 14 Two important financial fair play events were organised in the past two months: in September a UEFA club licensing and financial fair play workshop took place in Dublin, followed Sportsfile Cover: in October by a round table in Nyon. Lotta Schelin of Olympique Lyonnais gets in front of Joséphine Henning of Paris Saint-Germain in the first NEWS FROM MEMBER ASSOCIATIONS 15 leg of their UEFA Women’s Champions League round of 16 tie (1-1) technician No. 57 | November 2014 SUPPLEMENT EDITORIAL THE SHARING OF KNOWLEDGE Photo: E. -

Preparing for EURO 2004 How the Qualifiers Shaped up Germany Win

.03 11 Preparing for EURO 2004 03 How the qualifiers shaped up 06 Germany win the Women’s World Cup 09 Professional leagues 1010 no 19 – november 2003 – november no 19 COVER IN THIS ISSUE Professional leagues 10 Greece (Angelos Charisteas, in blue) Coach education directors will be taking part in their first EURO 2004 preparations in full swing 03 in Brussels 12 European Championship final round UEFA prepares for its jubilee 14 since 1980 and only their second ever. Review of the EURO 2004 qualifiers 06 News from member PHOTO: FLASH PRESS Germany win the Women’s World Cup 09 associations 17 AchievingEditorial the right balance The final tournament of the European Championship really started to take definite shape on 11 October, when Portugal found out the names of ten of their potential opponents and football fans were presented with the outline of what already shows all the signs of being a particularly mouth-watering line-up. Interest in the competition will be maintained in November with the play-offs, which promise to be exciting and open, and could give the final field of participants a very interesting look indeed. After these deciders, the draw for the final round will well and truly put us on tenterhooks in anticipation of the tournament itself and the fever will continue to mount until the opening match kicks off on 12 June 2004. For the supporters of the national teams which have not managed to qualify for next year’s European Championship final round, the draw for the 2006 World Cup qualifying competition at the beginning of December will give them renewed reason to hope and dream. -

Release List of up to 30 Players

Release list of up to 30 players Each association’s release list of up to 30 players was received by 11 May 2010 as per article 26 of the Regulations for the 2010 FIFA World Cup South Africa™. Mandatory rest period for players on the release list is from 17-23 May 2010 (except players involved in the UEFA Champions League final on 22 May). Each association must send FIFA a final list of no more than 23 players by 24.00 CET on 1 June 2010. Final list is limited to players on the release list submitted on 11 May 2010. Final list of 23 players will be published on FIFA.com at 12.00 CET on 4 June. Injured players may be replaced up to 24 hours before a team’s first match. Replacement players are not limited to the release list of up to 30 players. Liste de joueurs à libérer Les listes de joueurs à libérer (comportant jusqu’à 30 joueurs) ont été reçues de chaque association membre participante avant le 11 mai 2010 conformément à l’art. 26 du Règlement de la Coupe du Monde de la FIFA, Afrique du Sud 2010. La période de repos obligatoire à observer par les joueurs figurant sur la liste de joueurs à libérer (à l’exception des joueurs participant à la finale de la Ligue des Champions de l’UEFA le 22 mai) est du 17 au 23 mai 2010. Chaque association doit envoyer à la FIFA une liste définitive comportant un maximum de 23 joueurs au plus tard le 1er juin 2010 à minuit (heure centrale européenne). -

A Demostrar Su Crecimiento Con Un Bajo Perfil Los Griegos Son Peligrosos

24/04/2010 12:48 Cuerpo D Pagina 3 Cyan Magenta Amarillo Negro INTERNACIONAL | DOMINGO 25 DE ABRIL DE 2010 | EL SIGLO DE DURANGO 3 EL 11 IDEAL 1. ROMERO 15. HEINZE 5. SAMUEL 6. DEMICHELIS 17. JONAZ 4. ZANETTI 7. DIMARÍA 8. VERÓN 9. HIGUAÍN 2 2 14.MASCHERA- PLATEAMIENTO VECES SEMIFINALES MPEONES DEL EN COPA DEL MUNDO 4-3-3 MUNDO, EN LOGRADAS EN URUGUAY ENTINA 1978 Y 1930 E ITALIA 1990. ÉXICO 1986. 10. MESSI SELECCIONADO A demostrar su crecimiento S ■ Ahn Jung Hwan ■ Bae Ki Jong ■ Hwang Jae Won ■ Jeong Shung Hoon ■ Jung Sung Ryong ■ Kang Min Soo ■ y, Port Elizabeth Ki Sung Yueng ■ Kim Chi Woo COREA DEL SUR VS. GRECIA ■ Kim Hyun Gil nnesburgo ■ Kim Jin Kyu ARGENTINA VS. NIGERIA ■ Kim Nam Il annesburgo ■ Lee Chun Soo ARGENTINA VS. COREA DEL SUR ■ Lee Chung Yong emfontein ■ Lee Jung Soo GRECIA VS. NIGERIA ■ Lee Woon Jae Polokwane ■ Lee Young Pyo GRECIA VS. ARGENTINA ■ Oh Jang Eun da, Durban ■ Park Chu Young NIGERIA VS. COREA DEL SUR ■ Park Ji Sung ■ Seo Dong Hyeon ■ Seol Ki Hyeon ■ DT. Huh Jung Moo Este grupo le interesa a México porque si califica se vería con uno de los equipos de este sec- La República de Corea Dos de la eliminatoria asiática Park Ji-Sung desempeñó combinado nacional. tor. Por lo que podría repetirse el juego de octavos ante Argentina en el Mundial de Alemania. s el visitante asiático más con 16 puntos en ocho parti- un papel fundamental en las El nombramiento de Huh asiduo de la Copa Mundial de dos, cerrando con un empate dos anteriores campañas mun- Jung-Moo en diciembre de 5 la FIFA, y también el que más ante Irán, los asiáticos consi- dialistas de la República de Co- 2007 puso fin a la etapa de in- GOLES éxitos suma en la gran cita del guieron su séptima participa- rea, consolidándose como ca- fluencia holandesa, con técni- OBTUVO EL deporte rey. -

GREECE - SPAIN MATCH PRESS KIT EM Stadion Wals-Siezenheim, Salzburg Wednesday 18 June 2008 - 20.45CET (20.45 Local Time) Group D - Matchday 12

GREECE - SPAIN MATCH PRESS KIT EM Stadion Wals-Siezenheim, Salzburg Wednesday 18 June 2008 - 20.45CET (20.45 local time) Group D - Matchday 12 Contents 1 - Match preview 7 - Competition facts 2 - Match facts 8 - Team facts 3 - Squad list 9 - UEFA information 4 - Head coach 10 - Competition information 5 - Match officials 11 - Legend 6 - Match-by-match lineups Match background Spain are already assured first place in Group D and they wind up the first stage of UEFA EURO 2008™ by taking on Greece, whose reign as European champions came to a halt with their 1-0 defeat by Russia on Saturday. • That was a second defeat for Otto Rehhagel's Greece team following an opening 2-0 reverse against Sweden. If their fortunes could not have differed more greatly from four years ago, something similar could be said for Spain. • Spain drew 1-1 with Greece in their second outing at UEFA EURO 2004™ before a 1-0 defeat by Portugal then sent them spinning out of the tournament. Luis Aragonés's team, by contrast, made sure of their quarter-final place with a game to spare on Saturday after a last-gasp victory against Sweden. • David Villa's 92nd-minute goal snatched three points against Sweden after Zlatan Ibrahimović (34) had cancelled out Fernando Torres' 15th-minute opener. Villa built on his opening-game exploits against Russia, scoring a hat-trick (20, 44, 75) before Cesc Fàbregas (90+1) registered his first international goal in a 4-1 triumph. • Spain went into the teams' UEFA EURO 2004™ meeting in Porto as favourites and took a 28th-minute lead through Fernando Morientes, but a 66th-minute Angelos Charisteas strike earned Greece a share of the spoils. -

Goalden Times: December, 2011 Edition

GOALDEN TIMES 0 December, 2011 1 GOALDEN TIMES Declaration: The views and opinions expressed in this magazine are those of the authors of the respective articles and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Goalden Times. All the logos and symbols of teams are the respective trademarks of the teams and national federations. The images are the sole property of the owners. However none of the materials published here can fully or partially be used without prior written permission from Goalden Times. If anyone finds any of the contents objectionable for any reasons, do reach out to us at [email protected]. We shall take necessary actions accordingly. Cover Illustration: Neena Majumdar & Srinwantu Dey Logo Design: Avik Kumar Maitra Design and Concepts: Tulika Das Website: www.goaldentimes.org Email: [email protected] Facebook: Goalden Times http://www.facebook.com/pages/GOALden-Times/160385524032953 Twitter: http://twitter.com/#!/goaldentimes December, 2011 GOALDEN TIMES 2 GT December 2011 Team P.S. Special Thanks to Tulika Das for her contribution in the Compile&Publish Process December, 2011 3 GOALDEN TIMES | Edition V | First Whistle …………5 Goalden Times is all set for the New Year Euro 2012 Group Preview …………7 Building up towards EURO 2012 in Poland-Ukraine, we review one group at a time, starting with Group A. Is the easiest group really 'easy'? ‘Glory’ – We, the Hunters …………18 The internet-based football forums treat them as pests. But does a glory hunter really have anything to be ashamed of? Hengul -

GREECE RUSSIA Full-Time Report *

Match 18 Full-time report GRE-RUS Group A - Saturday 16 June 2012 National Stadium Warsaw - Warsaw GREECE 1-0 RUSSIA (1) (0) half time 20.45CET half time 13 Michalis Sifakis GK 16 Vyacheslav Malafeev GK 2 Giannis Maniatis 2 Aleksandr Anyukov 3 Giorgos Tzavellas 4 Sergei Ignashevich 5 Kyriakos Papadopoulos 5 Yuri Zhirkov Roman Shirokov 7 * Giorgos Samaras 6 7 Igor Denisov 10 Giorgos Karagounis C * * 10 Andrey Arshavin C 14 * Dimitris Salpingidis 11 Aleksandr Kerzhakov 15 * Vassilis Torossidis 12 Aleksei Berezutski 17 Fanis Gekas 17 Alan Dzagoev 19 Sokratis Papastathopoulos 22 * Denis Glushakov 21 Kostas Katsouranis 1 Kostas Chalkias GK 1 Igor Akinfeev GK 12 Alexandros Tzorvas GK 13 Anton Shunin GK 4 Stelios Malezas 3 Roman Sharonov 6 Grigoris Makos 9 Marat Izmailov 9 Nikos Liberopoulos 14 Roman Pavlyuchenko 11 Kostas Mitroglou 15 Dmitri Kombarov 16 Giorgos Fotakis 19 Vladimir Granat 18 Sotiris Ninis 20 Pavel Pogrebnyak 20 José Holebas 21 Kirill Nababkin 22 * Kostas Fortounis 23 Igor Semshov 23 Giannis Fetfatzidis Fernando Santos HC Dick Advocaat HC Half Full Half Full Attempts total 2 5 Attempts total 13 25 Attempts on target 2 2 Attempts on target 5 10 Saves 2 5 Saves 0 0 Corners 3 5 Corners 5 12 Offsides 1 1 Offsides 0 0 Fouls committed 4 8 Fouls committed 6 14 Fouls suffered 6 13 Fouls suffered 4 7 Free kicks to goal 0 0 Free kicks to goal 0 0 Possession 41% 38% Possession 59% 62% Ball in play 11'22" 21'13" Ball in play 16'40" 34'43" Total ball in play 28'02" 55'56" Total ball in play 28'02" 55'56" Referee: Fourth official: Jonas Eriksson (SWE) Hüseyin Göçek (TUR) Assistant referees: UEFA delegate: Stefan Wittberg (SWE) Geir Thorsteinsson (ISL) Mathias Klasenius (SWE) Additional assistant referees: Man of the match: Markus Strömbergsson (SWE) 10, Giorgos Karagounis (GRE) Stefan Johannesson (SWE) Attendance: 55,614 22:42:13CET Goal Y Booked R Sent off Substitution P Penalty O Own goal C Captain GK Goalkeeper * Misses next match if booked HC Head coach 16 Jun 2012 Fourth official:. -

European Qualifiers

EUROPEAN QUALIFIERS - 2014/16 SEASON MATCH PRESS KITS Stadio Georgios Karaiskakis - Piraeus Tuesday 14 October 2014 Greece 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Northern Ireland Group F - Matchday -10 Last updated 12/07/2021 17:07CET Official Partners of UEFA EURO 2020 Previous meetings 2 Match background 3 Squad list 4 Head coach 6 Match officials 7 Competition facts 8 Match-by-match lineups 9 Team facts 11 Legend 13 1 Greece - Northern Ireland Tuesday 14 October 2014 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Stadio Georgios Karaiskakis, Piraeus Previous meetings Head to Head UEFA EURO 2004 Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 11/10/2003 QR (GS) Greece - Northern Ireland 1-0 Athens Tsiartas 68 (P) 02/04/2003 QR (GS) Northern Ireland - Greece 0-2 Belfast Charisteas 4, 55 FIFA World Cup Stage Date Match Result Venue Goalscorers reached 17/10/1961 QR (GS) Northern Ireland - Greece 2-0 Belfast Mclaughlin 29, 57 Papaemanouil 9, 84; 03/05/1961 QR (GS) Greece - Northern Ireland 2-1 Athens McIlroy 85 Final Qualifying Total tournament Home Away Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L Pld W D L GF GA EURO Greece 1 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 - - - - 2 2 0 0 3 0 Northern Ireland 1 0 0 1 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 0 0 2 0 3 FIFA* Greece 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 2 3 Northern Ireland 1 1 0 0 1 0 0 1 - - - - 2 1 0 1 3 2 Friendlies Greece - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 1 0 0 3 2 Northern Ireland - - - - - - - - - - - - 1 0 0 1 2 3 Total Greece 2 2 0 0 2 1 0 1 - - - - 5 4 0 1 8 5 Northern Ireland 2 1 0 1 2 0 0 2 - - - - 5 1 0 4 5 8 * FIFA World Cup/FIFA Confederations Cup 2 Greece - Northern Ireland Tuesday 14 October 2014 - 20.45CET (21.45 local time) Match press kit Stadio Georgios Karaiskakis, Piraeus Match background The signs look good for Greece as they welcome Northern Ireland in UEFA EURO 2016 qualifying Group F, with three home wins in the sides' previous three encounters in Greece.