Sexual Violence by Security Forces in Egypt

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justice Denied: Mass Trials and the Death Penalty in Egypt

Justice Denied: Mass trials and the death penalty in Egypt November 2015 Executive Summary • 588 people have been sentenced to death in Egypt since 1 January 2014. • 72% of these sentences were handed down for involvement in political protests. • Executions are on the rise: between 2011 and 2013, only one execution was carried out. Since 2014 to date, at least 27 people have been executed. • At least 15 mass trials have taken place since March 2014. Reprieve has confirmed that at least 588 people have been sentenced to death in Egypt in less than two years. Our findings show that 72% of these people were sentenced to death for attending pro-democracy protests. The majority of the condemned have been sentenced in patently unjust mass trials, where tens, if not hundreds, of co-defendants are tried on near identical charges. The number of executions is also increasing, with at least 27 people having been executed by hanging in the last two years, compared to only one in the preceding three years. President Sisi has promised that the rate of executions will only increase as he aims to change the law to speed up executions1. Egypt’s system of mass trials defies international standards of due process and judicial independence. As part of a brutal crackdown on political opposition, thousands of people are being arrested. Many are then subjected to brutal prison conditions and torture, with scores of people dying in detention2. Reprieve calls on the Egyptian government to stop political mass trials and death sentences. Egypt’s policy of repressing those exercising their right to freedom of expression and assembly must end, and the rule of law must be upheld. -

Experimental Testes of Imbaba Railway Bridge

Al-Azhar University Civil Engineering Research Magazine (CERM) Vol. (41) No. (3) July, 2019 EXPERIMENTAL TESTES OF IMBABA RAILWAY BRIDGE 1 2 3 4 E.S.Youssef , H.M.Abbas , M.M.Saleh , M.A.Elewa 1 Master Student, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 2 Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. 3 Professor, Faculty of Engineering, CAIRO University, Giza, Egypt. 4 Assistant Professor, Faculty of Engineering, Al-Azhar University, Cairo, Egypt. ملخص البحث: تم تصميم جسور السكك الحديدية في مصر في الماضي لتعمل بشكل صحيح في ظل سيناريو تحميل محدد وظروف بيئية. لكن السيناريو الفعلي الذي يتعرض له الجسر يختلف تما ًما عما هو مصمم له. ذلك بسبب وجود الكثير من أوجه عدم اليقين في الحمولة القادمة على الهيكل وهناك دائ ًما احتمال انهيار الهيكل تحت الحمل الديناميكي. تم إجراء اختبار ثابت وديناميكي لدراسة أداء جسر سكة حديد إمبابة على نهر النيل بمحافظة القاهرة في ظل اختبار ثابت وديناميكي ، وكذلك ، استخراج المعامﻻت المشروطه )النمط ، التخميد ، والتردد الطبيعي(. ABSTRACT : The Railway Bridges in Egypt are designed at the past to perform properly under a definite loading scenario and environmental conditions. But the actual scenario to which a bridge is exposed is quite different than it is designed for. It is because there are lot of uncertainties in load coming over the structure and there is always a possibility for collapse of the structure under dynamic load. The static and dynamic test was carried out to study the performance of the Imbaba Railway Bridge over Nile River in Cairo governorate under ststic and dynamic test, also, extract modal parameter (mode shape, damping, and natural frequency). -

Egypt Healthcare GENERAL HOSPITALS CLINICS

The Pulse. 7th Edition 2017 Egypt Healthcare GENERAL HOSPITALS CLINICS We have a number of opportunities for healthcare We are seeking investors to partner with a service providers, where the market entry is recognized healthcare operator to establish possible by way of management agreement, Joint Clinics in: Venture and Long-term Lease of Land and/or > Riyadh Property. > Abu Dhabi > Riyadh > Sharjah > Cairo > Cairo > Ajman Possible modes of market entry include: > Dubai > Fujairah > Management Agreement > Joint Venture > Abu Dhabi > Long-term Lease of Land and/or Property Providers and Investors Seeking to Expand in the Middle East and North Africa Opportunities for Healthcare Service The opportunities are available in: LONG TERM CARE & CENTERS OF REHABILITATION CENTERS EXCELLENCE We are seeking to introduce well known Long- An established and recognized healthcare term Care and Rehabilitation providers to known provider is seeking to setup centers of investors in Cairo, Ajman, Abu Dhabi and Riyadh. excellence through management agreement, joint venture or long term lease. The way of dealing is available through: The opportunities The Specialties are: > Management Agreement are available in: > Ophthalmology > Joint Venture > Riyadh > Pediatric > Long-term Lease of Land > Cairo > Maternity and/or Property > Dubai > IVF > Abu Dhabi > Orthopedic > Sharjah > Beauty & Cosmetics > Ajman > Wellness > Fujairah Introduction Egypt is the most populous Arab Ian Albert Regional Director | Middle East and North Africa country in the world with Valuation and Advisory 94.7 million residing in Egypt [email protected] and 9.5 million living abroad. With a population growth rate of 2.2% per annum, this will continue to fuel demand for infrastructure services with a direct impact on the evolving Mansoor Ahmed Director | Middle East and North Africa urban landscape. -

Mints – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY

No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 No. TRANSPORT PLANNING AUTHORITY MINISTRY OF TRANSPORT THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT MiNTS – MISR NATIONAL TRANSPORT STUDY THE COMPREHENSIVE STUDY ON THE MASTER PLAN FOR NATIONWIDE TRANSPORT SYSTEM IN THE ARAB REPUBLIC OF EGYPT FINAL REPORT TECHNICAL REPORT 11 TRANSPORT SURVEY FINDINGS March 2012 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS CO., LTD. ALMEC CORPORATION EID KATAHIRA & ENGINEERS INTERNATIONAL JR - 12 039 USD1.00 = EGP5.96 USD1.00 = JPY77.91 (Exchange rate of January 2012) MiNTS: Misr National Transport Study Technical Report 11 TABLE OF CONTENTS Item Page CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION..........................................................................................................................1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND...................................................................................................................................1-1 1.2 THE MINTS FRAMEWORK ................................................................................................................1-1 1.2.1 Study Scope and Objectives .........................................................................................................1-1 -

Flood-Induced Scour in the Nile by Modified Operation of High Aswan Dam

Conference Paper, Published Version Sloff, C. J.; El-Desouky, I. A. Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam Verfügbar unter/Available at: https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11970/100075 Vorgeschlagene Zitierweise/Suggested citation: Sloff, C. J.; El-Desouky, I. A. (2006): Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam. In: Verheij, H.J.; Hoffmans, Gijs J. (Hg.): Proceedings 3rd International Conference on Scour and Erosion (ICSE-3). November 1-3, 2006, Amsterdam, The Netherlands. Gouda (NL): CURNET. S. 614-621. Standardnutzungsbedingungen/Terms of Use: Die Dokumente in HENRY stehen unter der Creative Commons Lizenz CC BY 4.0, sofern keine abweichenden Nutzungsbedingungen getroffen wurden. Damit ist sowohl die kommerzielle Nutzung als auch das Teilen, die Weiterbearbeitung und Speicherung erlaubt. Das Verwenden und das Bearbeiten stehen unter der Bedingung der Namensnennung. Im Einzelfall kann eine restriktivere Lizenz gelten; dann gelten abweichend von den obigen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. Documents in HENRY are made available under the Creative Commons License CC BY 4.0, if no other license is applicable. Under CC BY 4.0 commercial use and sharing, remixing, transforming, and building upon the material of the work is permitted. In some cases a different, more restrictive license may apply; if applicable the terms of the restrictive license will be binding. Flood-induced scour in the Nile by modified operation of High Aswan Dam C.J. Sloff* and I.A. El-Desouky ** * WL | Delft Hydraulics and Delft University of Technology, Delft, Netherlands ** Hydraulics Research Institute (HRI), Delta Barrage, Cairo, Egypt Due to climate-change it is anticipated that the hydrological m. -

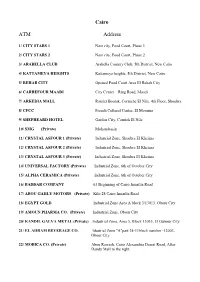

Cairo ATM Address

Cairo ATM Address 1/ CITY STARS 1 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 1 2/ CITY STARS 2 Nasr city, Food Court, Phase 2 3/ ARABELLA CLUB Arabella Country Club, 5th District, New Cairo 4/ KATTAMEYA HEIGHTS Kattameya heights, 5th District, New Cairo 5/ REHAB CITY Opened Food Court Area El Rehab City 6/ CARREFOUR MAADI City Center – Ring Road, Maadi 7/ ARKEDIA MALL Ramlet Boulak, Corniche El Nile, 4th Floor, Shoubra 8/ CFCC French Cultural Center, El Mounira 9/ SHEPHEARD HOTEL Garden City, Cornish El Nile 10/ SMG (Private) Mohandessin 11/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 1 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 12/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 2 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 13/ CRYSTAL ASFOUR 3 (Private) Industrial Zone, Shoubra El Kheima 14/ UNIVERSAL FACTORY (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 15/ ALPHA CERAMICA (Private) Industrial Zone, 6th of October City 16/ BADDAR COMPANY 63 Beginning of Cairo Ismailia Road 17/ ABOU GAHLY MOTORS (Private) Kilo 28 Cairo Ismailia Road 18/ EGYPT GOLD Industrial Zone Area A block 3/13013, Obour City 19/ AMOUN PHARMA CO. (Private) Industrial Zone, Obour City 20/ KANDIL GALVA METAL (Private) Industrial Zone, Area 5, Block 13035, El Oubour City 21/ EL AHRAM BEVERAGE CO. Idustrial Zone "A"part 24-11block number -12003, Obour City 22/ MOBICA CO. (Private) Abou Rawash, Cairo Alexandria Desert Road, After Dandy Mall to the right. 23/ COCA COLA (Pivate) Abou El Ghyet, Al kanatr Al Khayreya Road, Kaliuob Alexandria ATM Address 1/ PHARCO PHARM 1 Alexandria Cairo Desert Road, Pharco Pharmaceutical Company 2/ CARREFOUR ALEXANDRIA City Center- Alexandria 3/ SAN STEFANO MALL El Amria, Alexandria 4/ ALEXANDRIA PORT Alexandria 5/ DEKHILA PORT El Dekhila, Alexandria 6/ ABOU QUIER FERTLIZER Eltabia, Rasheed Line, Alexandria 7/ PIRELLI CO. -

Fossil Fuel Subsidy and Pricing Policies

WPS7531 Policy Research Working Paper 7531 Public Disclosure Authorized Fossil Fuel Subsidy and Pricing Policies Recent Developing Country Experience Public Disclosure Authorized Masami Kojima Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Energy and Extractives Global Practice Group January 2016 Policy Research Working Paper 7531 Abstract The steep decline in the world oil price in the last quarter Recent experience suggests that regular and frequent of 2014 slashed fuel price subsidies. Several governments price adjustments, however small—as in Jordan and responded by announcing that they would remove subsidies Morocco—help the government and consumers to get for one or more fuels and move to market-based pricing accustomed to fluctuations in world fuel prices and with full cost recovery. Other governments took advantage exchange rates. By contrast, freezing prices, even for a few of low world prices to increase taxes and other charges on months—for socioeconomic considerations or because fuels. However, the decision to move to cost recovery and the needed adjustments are small enough to be absorbed— market prices, ending budgetary support, has not been increases the risk of reversion to ad hoc pricing and price implemented consistently across countries. Policy announce- subsidies. The more formally the decision to move to ments have varied in the way they were communicated and market-based pricing is communicated, the more public the level of detail provided. When petroleum product prices new price announcements, and the higher the frequency bounced back during the first half of 2015, some “reform- of price changes, the more likely the implementation of ing” governments failed to raise prices correspondingly. -

Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel

All “Islamic Terrorism” Is Perpetrated by Fundamentalist Sunnis, Except Terrorism Against Israel By Eric Zuesse Region: Middle East & North Africa Global Research, June 10, 2017 Theme: Terrorism, US NATO War Agenda In-depth Report: IRAN: THE NEXT WAR?, IRAQ REPORT, SYRIA My examination of 54 prominent international examples of what U.S.President Donald Trump is presumably referring to when he uses his often-repeated but never defined phrase “radical Islamic terrorism” indicates that it is exclusively a phenomenon that is financed by the U.S. government’s Sunni fundamentalist royal Arab ‘allies’ and their subordinates, and not at all by Iran or its allies or any Shiites at all. Each of the perpetrators was either funded by those royals, or else inspired by the organizations, such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, that those royals fund, and which are often also armed by U.S.-made weapons that were funded by those royals. In other words: the U.S. government is allied with the perpetrators. Iran’s President Hassan Rouhani and Syrian counterpart Bashar al-Assad (Source: antiliberalnews.net) See the critique of this article by Kevin Barrett Stop the Smear Campaign (and Genocide) Against Sunni Islam!By Kevin Barrett, June 13, 2017 Though U.S. President Donald Trump blames Shias, such as the leaders of Iran and of Syria, for what he calls “radical Islamic terrorism,” and he favors sanctions etc. against them for that alleged reason, those Shia leaders and their countries are actually constantly being attacked by Islamic terrorists, and this terrorism is frequently perpetrated specifically in order to overthrow them (which the U.S. -

De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula

Policy Briefing April 2017 De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz De-Securitizing Counterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz The Brookings Institution is a private non-profit organization. Its mission is to conduct high-quality, independent research and, based on that research, to provide innovative, practical recommendations for policymakers and the public. The conclusions and recommendations of any Brookings publication are solely those of its author(s), and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Institution, its management, or its other scholars. Brookings recognizes that the value it provides to any supporter is in its absolute commitment to quality, independence and impact. Activities supported by its donors reflect this commitment and the analysis and recommendations are not determined by any donation. Copyright © 2017 Brookings Institution BROOKINGS INSTITUTION 1775 Massachusetts Avenue, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20036 U.S.A. www.brookings.edu BROOKINGS DOHA CENTER Saha 43, Building 63, West Bay, Doha, Qatar www.brookings.edu/doha III De-Securitizing Counterterrorism in the Sinai Peninsula Sahar F. Aziz1 On October 22, 2016, a senior Egyptian army ideal location for lucrative human, drug, and officer was killed in broad daylight outside his weapons smuggling (much of which now home in a Cairo suburb.2 The former head of comes from Libya), and for militant groups to security forces in North Sinai was allegedly train and launch terrorist attacks against both murdered for demolishing homes and -

Afdb Portfolio in Egypt (September 2017)

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK Public Disclosure Authorized Authorized Public Disclosure EGYPT SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT OF ABU RAWASH WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT (ABU-RAWASH-WWTP) APPRAISAL REPORT Authorized Authoriezd Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure RDGN/AHWS November 2017 TABLE OF CONTENTS I – STRATEGIC THRUST & RATIONALE ............................................................................ 1 1.1 Project linkages with country strategy and objectives ......................................................... 1 1.2. Rationale for Bank’s involvement ...................................................................................... 1 1.3. Donor coordination ............................................................................................................. 2 II – PROJECT DESCRIPTION ................................................................................................. 3 2.1. Project components ............................................................................................................. 3 2.2. Technical solution retained and other alternatives explored ............................................... 3 2.3. Project type ......................................................................................................................... 4 2.4. Project cost and financing arrangements ............................................................................ 4 2.5. Project’s target area and population ................................................................................... -

The Struggle for Worker Rights in EGYPT AREPORTBYTHESOLIDARITYCENTER

67261_SC_S3_R1_Layout 1 2/5/10 6:58 AM Page 1 I JUSTICE I JUSTICE for ALL for I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I “This timely and important report about the recent wave of labor unrest in Egypt, the country’s largest social movement ALL The Struggle in more than half a century, is essential reading for academics, activists, and policy makers. It identifies the political and economic motivations behind—and the legal system that enables—the government’s suppression of worker rights, in a well-edited review of the country’s 100-year history of labor activism.” The Struggle for Worker Rights Sarah Leah Whitson Director, Middle East and North Africa Division, Human Rights Watch I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I I for “This is by far the most comprehensive and detailed account available in English of the situation of Egypt’s working people Worker Rights today, and of their struggles—often against great odds—for a better life. Author Joel Beinin recounts the long history of IN EGYPT labor activism in Egypt, including lively accounts of the many strikes waged by Egyptian workers since 2004 against declining real wages, oppressive working conditions, and violations of their legal rights, and he also surveys the plight of A REPORT BY THE SOLIDARITY CENTER women workers, child labor and Egyptian migrant workers abroad. -

A Death Foretold, P. 36

Pending Further Review One year of the church regularization committee A Death Foretold* An analysis of the targeted killing and forced displacement of Arish Coptic Christians First edition November 2018 Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights 14 al Saray al Korbra St., Garden City, Al Qahirah, Egypt. Telephone & fax: +(202) 27960197 - 27960158 www.eipr.org - [email protected] All printing and publication rights reserved. This report may be redistributed with attribution for non-profit pur- poses under Creative Commons license. www.creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0 *The title of this report is inspired by Colombian Nobel laureate Gabriel García Márquez’s novel Chronicle of a Death Foretold (1981) Acknowledgements This report was written by Ishak Ibrahim, researcher and freedom of religion and belief officer, and Sherif Mohey El Din, researcher in Criminal Justice Unit at EIPR. Ahmed Mahrous, Monitoring and Documentation Officer, contributed to the annexes and to acquiring victim and eyewitness testimonials. Amr Abdel Rahman, head of the Civil Liberties unit, edited the report. Ahmed El Sheibini did the copyediting. TABLE OF CONTENTS: GENERAL BACKGROUND OF SECTARIAN ATTACKS ..................................................................... 8 BACKGROUND ON THE LEGAL AND SOCIAL CONTEXT OF NORTH SINAI AND ITS PARTICULARS ............................................................................................................................................. 12 THE LEGAL SITUATION GOVERNING NORTH SINAI: FROM MILITARY COMMANDER DECREES