Sample Pages

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Midsummer Night's Dream, by William Shakespeare Being Most

A Midsummer Night's Dream, by William Shakespeare Being Most Shamelessly Condensed for a Small Company and Limited Duration by Jennifer Moser Jurling With Mechanics Set Forth for Use in the Role-Playing Game The Play's the Thing, by Mark Truman With Thanks to MIT for http://shakespeare.mit.edu/ DRAMATIS PERSONAE OBERON, king of Faerie. Part: Faerie. Plot: Betrayer to Titania. Prop: Lantern. PUCK, servant to Oberon. Part: Faerie. Plot: Sworn to Oberon. Prop: Disguise. TITANIA: queen of Faerie. Part: Faerie. Plot: Rival to Oberon. Prop: Coin. THESEUS: duke of Athens. Part: Ruler. Plot: In Love with Hippolyta. Prop: Crown. HIPPOLYTA: queen of Amazons. Part: Maiden. Plot: In Love with Theseus. Prop: Crown. PETER QUINCE: director, Athens Acting Guild. Part: Hero. Plot: Rival to Nick Bottom. Prop: Letter. NICK BOTTOM: actor in the guild. Part: Fool. Plot: Rival to Peter Quince. Prop: Lantern. SNUG: actor in the guild. Part: Commoner. Plot: Friend to Peter Quince. Prop: Disguise. Note to Playwright: You may wish to use “In Love with Hippolyta” as Oberon’s starting plot and “In Love with Theseus” as Titania’s starting plot. Of course, these can also be added later or not at all. ACT I Faerie king Oberon and his queen, Titania, quarrel. (Titania has a changeling human boy among her attendants, and she refuses to let him be one of Oberon’s henchmen. They also argue over Oberon’s love for Hippolyta and Titania’s love for Theseus.) Oberon enlists his servant Puck to fetch a flower that will enable him to cast a love spell on Titania, so that she will fall in love with a monstrous beast. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

THE SHAKESPEARE THEATRE OF NEW JERSEY EDUCATION PRESENTS SHAKESPEARE LIVE! 2017 A Midsummer Night’s Dream BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE STUDENT-TEACHER STUDY GUIDE COMPILED AND ARRANGED BY THE EDUCATION DEPARTMENT OF THE SHAKESPEARE THEATRE OF NEW JERSEY Shakespeare LIVE!, The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey’s educational touring company, is part of Shakespeare in American Communities: Shakespeare for a New Generation, a national program of the National Endowment for the Arts in cooperation with Arts Midwest. Additional support for Shakespeare LIVE! is provided by The Investors Foundation, Johnson & Johnson, The Provident Bank Foundation, and the Turrell Fund. COVER: Mustardseed, Peasblossom and Moth from the 2015 touring production of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM THIS PAGE: The Mechanicals from the 2015 touring production of A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM. ALL PHOTOS by Jerry Dahlia ©2015 unless noted. In This Guide: Classroom Activities for Teachers and Students ...............................p2 Shakespeare: Helpful Tips For Exploring & Seeing His Works .......p3 About the Playwright ................................................................................p4 Shakespeare’s London .............................................................................p5 Shakespeare’s Verse ..................................................................................p6 “Are you SURE this is English?” .............................................................. p7 A Midsummer Night’s Dream: An Introduction ...................................p8 Midsummer: -

The Function of Forest in the Faerie Queene: Seeing the Woods for the Trees

The Function of Forest in The Faerie Queene: Seeing the Woods for the Trees Nicholas Randell April 1987 The Function o£ Forest in The Faerie Queene: Seeing the Woods £or the Trees Nicholas Randell April 1987 Generally, the mention of place in\regard to/The Faerie Queene summons up the image of Alma's House of Temperance, the Bower of Bliss, or Isis' Temple. These settings are highly stagey: the narrative comes to a halt) and the reader is expected to interpret the composite images of the scene. The crocodile at Isis' feet enJoys the same relationship to her as Justice does to equity. Equity, its allegorical representative embodied in Isis, exercises a restraining influence over the "cruel doome" of Justice, i.e., the crocodile that Isis stands on. These places smack of the unreal; they and their set pieces exist primarily to illustrate a moral orientation or philosophical position. In Acrasia's Bower of Bliss, of course, unreality is Just the point. With its "painted flowres" it caters to the whims of the men it hopes to ensnare. The Bower exists for them. It is made to please: "The dales for shade, the hills for breathing space"! (The Faerie Queene. II, xii,5S) But what of place when The Faerie Queen's narrative rolls right along? What about the landscape that doesn't make man happy or remind him of one or another truth? All the symbolic places of The Faerie Queen are, in a very real sense, interludes of a larger piece, brief moments in a landscape that undulates about them. -

Written by 'L'ravis Beacham No Portion of This Script Lna.Y

,. KILLING ON CARNIVAL ROW Written by 'l'ravis Beacham No portion o.f this script lna.y be performed, reproduced, or .used by any means, or quoted or published in any ·medium without the ·prior: written consent of Kopelso:il Entertainment. · ·r·.,, ___ '¥.. ! July 22, 2005 . ·.~·:;, © 2005 . KOPELSON EN'l'ER'l'AI.NMEN'l' All Rights Reserved · EXT. SEWER TUNNEL -- NIGHT not just a "broken and bent archway" An archway at the end of an alley. Broken and bent long . ' ago, crnsted with moss. A trickle of water cuts through. not just "wet" A SCREAM from within. Laboured BREATHING, the rapid SPLISH SP:LASH of footfalls. AISLING COBWEB, beautiful and intense, bursts from the tunnel into the narrow alley. doesn't just come out, but "bursts" Her body, petite, young, and frail, tense with fear. From her back sprout a pair of large moth-like wings, fragile, intricate, frayed at the edges. tells us exactly why/how her wings are fragile Aisling Cobweb is a faerie. And she's running for her life. She catches her tattered skirt on !lletal grating and stumbles face first. she turns, panicked. ·· In the darkness, distant at first, an eerie WAIL. Her eyes widen. "tattered skin" tells us Aisling, flexes her wings, and takes to she has already been caught. so she is not just THE AIR running. she is escaping. with frantic agility. She flies, weaving between narrow ) alleys, dodging gas lanterns and sagging clothes-lines. She is not just Her papery wings carry her swerving around tight corners. running, she is "weaving and She slams into the s.ide of a steep inclined dodging." But ROOF not just "weaving and where she scrambles for a foothold on the.slate-shingles. -

Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96;

. MC0111117 VESUI17 Ell 1E5 570 ' CS 20 5 4,96; AUTHOR McLean, Ardrew M. TITLE . ,A,Shakespeare: Annotated BibliographiesendAeaiaGuide 1 47 for Teachers. .. INSTIT.UTION. NIttional Council of T.eachers of English, Urbana, ..Ill. .PUB DATE- 80 , NOTE. 282p. AVAILABLe FROM Nationkl Coun dil of Teachers,of Englishc 1111 anyon pa., Urbana, II 61.801 (Stock No. 43776, $8.50 member, . , $9.50 nor-memberl' , EDRS PRICE i MF011PC12 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Biblioal7aphies: *Audiovisual Aids;'*Dramt; +English Irstruction: Higher Education; 4 *InstrUctioiral Materials: Literary Criticism; Literature: SecondaryPd uc a t i on . IDENTIFIERS *Shakespeare (Williaml 1 ABSTRACT The purpose of this annotated b'iblibigraphy,is to identify. resou'rces fjor the variety of approaches tliat teachers of courses in Shakespeare might use. Entries in the first part of the book lear with teaching Shakespeare. in secondary schools and in college, teaching Shakespeare as- ..nerf crmance,- and teaching , Shakespeare with other authora. Entries in the second part deal with criticism of Shakespearear films. Discussions of the filming of Shakespeare and of teachi1g Shakespeare on, film are followed by discu'ssions 'of 26 fgature films and the,n by entries dealing with Shakespearean perforrances on televiqion: The third 'pax't of the book constituAsa glade to avAilable media resources for tlip classroom. Ittries are arranged in three categories: Shakespeare's life'and' iimes, Shakespeare's theater, and Shakespeare 's plam. Each category, lists film strips, films, audi o-ca ssette tapes, and transparencies. The.geteral format of these entries gives the title, .number of parts, .grade level, number of frames .nr running time; whether color or bie ack and white, producer, year' of .prOduction, distributor, ut,itles of parts',4brief description of cOntent, and reviews.A direCtory of producers, distributors, ard rental sources is .alst provided in the 10 book.(FL)- 4 to P . -

Fairy Tale: a Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner

Volume 37 Number 2 Article 12 Spring 4-17-2019 Fairy Tale: A Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner Barbara L. Prescott Stanford University Alumni Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, English Language and Literature Commons, and the Folklore Commons Recommended Citation Prescott, Barbara L. (2019) "Fairy Tale: A Very Short Introduction by Marina Warner," Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: Vol. 37 : No. 2 , Article 12. Available at: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/12 This Book Reviews is brought to you for free and open access by the Mythopoeic Society at SWOSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature by an authorized editor of SWOSU Digital Commons. An ADA compliant document is available upon request. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To join the Mythopoeic Society go to: http://www.mythsoc.org/join.htm Mythcon 51: A VIRTUAL “HALFLING” MYTHCON July 31 - August 1, 2021 (Saturday and Sunday) http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-51.htm Mythcon 52: The Mythic, the Fantastic, and the Alien Albuquerque, New Mexico; July 29 - August 1, 2022 http://www.mythsoc.org/mythcon/mythcon-52.htm This book reviews is available in Mythlore: A Journal of J.R.R. Tolkien, C.S. Lewis, Charles Williams, and Mythopoeic Literature: https://dc.swosu.edu/mythlore/vol37/iss2/12 EVIEW ESSAYS NAVIGATING THE C ARTE DU TENDRE IN FA IRY T ALE: A V ERY SH ORT INTRODUCTION BY MAR INA WARNER BARBARA PRESCOTT FAIRY TALE: A VERY SHORT INTRODUCTION. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM: Know-the-Show Guide A Midsummer Night’s Dream by William Shakespeare Know-the-Show Audience Guide researched and written by the Education Department of Artwork by Scott McKowen The Shakespeare Theatre of New Jersey A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM: Know-the-Show Guide In This Guide – The Life of William Shakespeare ............................................................................................... 2 – A Midsummer Night’s Dream: An Introduction ......................................................................... 3 – A Midsummer Night’s Dream: A Synopsis ................................................................................. 4 – Who’s Who in the Play ............................................................................................................. 6 – Sources and History .................................................................................................................. 7 – Aspects of Midsummer ............................................................................................................. 8 – Midsummer Tidbits ................................................................................................................. 10 – Commentary & Criticism ........................................................................................................ 11 – Theatre in Shakespeare’s Day .................................................................................................. 12 – In this Production .................................................................................................................. -

The Origins of Shakespeare's Oberon

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-02451-9 - Shakespeare Survey: 65: A Midsummer Night’s Dream Edited By Peter Holland Excerpt More information ‘A LOCAL HABITATION AND A NAME’: THE ORIGINS OF SHAKESPEARE’S OBERON LAURA AYDELOTTE ‘ . but the way is so full of ye fayrey & straunge play The Scottish Historie of James the Fourth as thynges, that such as passe that way are lost, for a way of inquiring into the origins of Shake- in that wood abydyth a kynge of ye fayrey namyd speare’s Oberon. The fairy king of the sources is Oberon’.1 So the French knight, Huon de Bor- an often contradictory character, at once a benefi- deaux, is warned as he continues his journey in cent guide and a darkly powerful threat; a meddle- quest of four teeth and a tuft of the beard of some trickster and a haughtily detached observer Babylon’s ruler, Admiral Gaudys. Literary schol- of human affairs. Understanding these mixed ori- ars looking at mortals lost in another wood full of gins not only provides new insights into the ways fairy and strange things in Shakespeare’s AMid- in which Shakespeare’s Oberon was shaped by his summer Night’s Dream have long identified Sir John predecessors but also suggests that certain aspects Bourchier, Lord Berners’s 1534 English translation of Puck’s character and the relationship between of the French romance Huon de Bordeaux as the Puck and Oberon are indebted to the single fig- source for two aspects of the fairy king in Shake- ure of the fairy king in previous texts. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

illuminations A guide to the 2020 plays A Midsummer Night’s Dream Illuminations | 1 Hippolyta: An Amazonian warrior queen who has been bested by Theseus in war. The two are set to be married four days from the start of the play. Philostrate: The master of ceremonies for Theseus’s court. Egeus: Hermia’s father, who is stuck in his ways. He wants Hermia to marry Demetrius rather than Lysander and gives her the options of death, a convent or marrying Demetrius. Hermia: Hermia devises a plan to run away with Lysander to a relative’s house beyond the woods of Athens where they can be together. Lysander: He is hopelessly in love with Hermia. Once in the woods, Lysander is mistaken for Demetrius and magically falls in love with Helena. Demetrius: Demetrius ended his previous relationship with Helena in order to pur- sue Hermia instead. Demetrius is favored by Hermia’s father. Helena: Hermia’s best friend. Helena still loves Demetrius. Mechanicals Nick Bottom: A weaver, Bottom believes in his ability to act and perform any part. The other mechanicals look to him for guidance. Peter Quince: A carpenter by trade who serves as the director, stage manager and dramaturg for the mechanicals. Snug: A joiner who plays the lion in Pyramus and Thisbe. A Midsummer Tom Snout: A tinker (a metalworker, especially on household utensils) who plays Night’s Dream the wall. Francis Flute: A bellows-mender who plays Thisbe. William Shakespeare Who’s Who Directed by Joseph Haj Robin Starveling: A tailor who plays Athenians Moonshine. Notes by Isabel Smith-Bernstein Theseus: The Duke of Athens. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

2019-2020 WORLDCLASS® A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM Friday, November 1, 2019 10:15 am - 12:45 pm Sandler Center for the Performing Arts, Virginia Beach What’s Inside: VAF Education Sponsors 2 Who Was Shakespeare and Why Should I Care? 8-9 American Shakespeare Center 3 Shakespeare’s England: The Elizabethan Age 10 A Midsummer Night’s Dream 4-5 The Theater Experience: Shakespeare’s Day and Today 11 Who’s Who in A Midsummer Night’s Dream 6 For Better or Verse 12-13 Master of the Mashup: Shakespeare and His Resources 14 Midsummer Sources 7 vafest.org VAF EDUCATION SPONSORS 2 THANK YOU TO ALL OF OUR DONORS AND THESE SPONSORS OF VIRGINIA ARTS FESTIVAL EDUCATION PROGRAMS CORPORATE SPONSORS FOUNDATIONS D. Baker Ames Charitable Foundation, East Beach Institute, Leah S. Wohl Musical Arts Fund of the Hampton Clark Nexsen, Enterprise Holdings Foundation, Roads Community Foundation, ODU Hixon Nordstrom, USAA, Wells Fargo Community Engagement Fund, Ruth Brown Memorial Fund GOVERNMENT SUPPORT The following cities and/or their Arts and Humanities Commissions: Chesapeake, Newport News, Norfolk, Portsmouth, Virginia Beach, and Williamsburg. VIRGINIA ARTS FESTIVAL // A MIDSUMMER NIGHT’S DREAM AMERICAN SHAKESPEARE CENTER 3 The American Shakespeare Center celebrates the joys and accessibility of Shakespeare’s theatre, language, and humanity by exploring the English Renaissance stage and its practices through performance and education. With its performances, theater, exhibitions, and educational programs, the ASC seeks to make Shakespeare, the joys of theatre and language, and the communal experience of the Renaissance stage accessible to all. By re-creating Renaissance conditions of performance, the ASC explores its repertory of plays for a better understanding of these great works and of the human theatrical enterprise past, present, and future. -

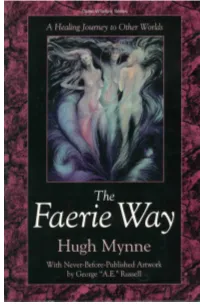

The Faerie Way.Pdf

The Way of the Shining Realm Faeries are very real and powerful energy beings who exist in a dimension parallel to our own. These beings embody the enlight- ened energy of the elements, and the wisdom, energy, and primal force of creation. In this book you'll learn to work with the Sidhe, the faeries of the shining realm, to bridge polarities within your psyche, the world, and the universe. Meet the great adepts of the Faerie Tradition, including Thomas the Rhymer, who traveled bodily into Faerieland. Learn how you can enter the Faerie realm and meet animal helpers and faerie allies that will help you realign with the natural world. Travel to the mystic cities of the Faerie realm to harmonize your inner and outer worlds. Then travel deeper into Faerieland and become an initiate of the Faerie Way to transform yourself from the spirit outward. Finally, tap the energy of the life-force itself and achieve ultimate wholeness when you merge with your "Co- Walker" in the Faerie world. For Wiccans, the Faerie Way offers deep spiritual springs of renewal. For those on other paths, it provides a much-needed nondualistic, shamanic alternative to standard Western magical cosmology. The path into Faerieland lies open to everyone. If you're a seeker who longs to find "the land of heart's desire," The Faerie Way will guide your steps. About the Author Llewellyn's Celtic Wisdom Series Hugh Mynne was bom in 1950 in Crosby, England. He graduated from the University College of North Wales with a B.A. -

A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare

ASF 2016 Study Materials & Activities for A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Director Set Design Costume Design Lighting Design Diana Van Fossen James Wolk Brenda Van der Wiel Travis MaCale Contact ASF at: www.asf.net Study materials written by 1.800.841-4273 Susan Willis, ASF Dramaturg [email protected] ASF/ 1 A Midsummer Night's Dream by William Shakespeare Welcome to A Midsummer Night's Dream Shakespeare's comedies are among the glories of drama, and none is more Characters glorious than A Midsummer Night's at court: Dream, a hearty confection of myth and Theseus, Duke of Athens magic, court and country, aristocrat and Hippolyta, queen of the artisan. It dazzles with the delights of its Amazons fairy kingdom, its confused lovers, and its Egeus, a lord at court earnest amateur acting troupe—and any Hermia, his daugher play that puts donkey ears on a blowhard Titania Lysander, beloved of Hermia is sure to please. It moves toward a spate asleep Demetrius, the man Egeus of weddings and the funniest rendition in her wants Hermia to marry of a tragedy known to theatre. Along the bower, Helena, in love with Demetrius way, Shakespeare weaves four plots into and, like the Philostrate, a lord a joyous comic pattern that divides and reunites, dreams and awakens, enchants lovers, and enlightens. about to in the town: awaken Peter Quince, a carpenter to new Nick Bottom, a weaver who The Story "love" plays Pyramus Trouble at Court Francis Flute, a bellows Having defeated Hippolyta in battle, the others. Bottom's singing then awakens mender who plays Thisbe Theseus now plans to wed this Queen of the the flower-charmed Titania, and she falls Tom Snout, a tinker who plays Amazons.