Cecal Fermentation in Mallards in Relation to Diet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Gyrfalcon Diet in Central West Greenland During the Nesting Period

The Condor 105:528±537 q The Cooper Ornithological Society 2003 GYRFALCON DIET IN CENTRAL WEST GREENLAND DURING THE NESTING PERIOD TRAVIS L. BOOMS1,3 AND MARK R. FULLER2 1Boise State University Raptor Research Center, 1910 University Drive, Boise, ID 83725 2USGS Forest and Rangeland Ecosystem Science Center, 970 Lusk St., Boise, ID 83706 Abstract. We studied food habits of Gyrfalcons (Falco rusticolus) nesting in central west Greenland in 2000 and 2001 using three sources of data: time-lapse video (3 nests), prey remains (22 nests), and regurgitated pellets (19 nests). These sources provided different information describing the diet during the nesting period. Gyrfalcons relied heavily on Rock Ptarmigan (Lagopus mutus) and arctic hares (Lepus arcticus). Combined, these species con- tributed 79±91% of the total diet, depending on the data used. Passerines were the third most important group. Prey less common in the diet included waterfowl, arctic fox pups (Alopex lagopus), shorebirds, gulls, alcids, and falcons. All Rock Ptarmigan were adults, and all but one arctic hare were young of the year. Most passerines were ¯edglings. We observed two diet shifts, ®rst from a preponderance of ptarmigan to hares in mid-June, and second to passerines in late June. The video-monitored Gyrfalcons consumed 94±110 kg of food per nest during the nestling period, higher than previously estimated. Using a combi- nation of video, prey remains, and pellets was important to accurately document Gyrfalcon diet, and we strongly recommend using time-lapse video in future diet studies to identify biases in prey remains and pellet data. Key words: camera, diet, Falco rusticolus, food habits, Greenland, Gyrfalcon, time-lapse video. -

Nesting Behavior of Female White-Tailed Ptarmigan in Colorado

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 215 Condor, 81:215-217 0 The Cooper Ornithological Society 1070 NESTING BEHAVIOR OF FEMALE settling on the clutches. By lifting the hens off their WHITE-TAILED PTARMIGAN nests, we learned that eggs were laid almost immedi- ately after settling. IN COLORADO After eggs were laid, the hens remained relatively inactive until they prepared to depart from the nest. Observations of six hens in 1975 indicated that they KENNETH M. GIESEN remained on the nest for longer periods as the clutch AND approached completion. One hen depositing her sec- ond egg remained on her nest for 44 min, whereas CLAIT E. BRAUN another, depositing the fifth egg of a six-egg clutch, remained on the nest more than 280 min. Three hens remained on their nests 84 to 153 min when laying Few detailed observations on behavior of nesting their second or third eggs. Spruce Grouse also show grouse have been reported. Notable exceptions are this pattern of nest attentiveness (McCourt et al. those of SchladweiIer (1968) and Maxson (1977) 1973). who studied feeding behavior and activity patterns of Before departing from the nest, the hen began to Ruffed Grouse (Bonasa umbellus) in Minnesota, and peck at vegetation and place it at the rim of the McCourt et al. ( 1973) who documented nest atten- nest, or throw it over her back. This behavior lasted tiveness of Spruce Grouse (Canachites canudensis) in 34, 40 and 64 min for three hens. Vegetation was southwestern Alberta. White-tailed Ptarmigan (Lugo- deposited on the nest at the rate of 20 pieces per pus Zeucurus) have been intensively studied in Colo- minute. -

Driven Grouse Shooting

Driven grouse shooting RSPB Council updated our previous policy on driven grouse shooting in October 2020. Our policy is to support licensing of driven grouse shooting across the UK, following expected progress on this issue in Scotland in 2020. Unless substantial progress (including effective licensing, stopping raptor killing, cessation of burning on peat soils, and banning use of lead ammunition) is made in reforming driven grouse shooting by 2025 in line with RSPB principles for sustainable gamebird shooting, we will consequently call on governments to introduce a specific ban on driven grouse shooting. Background Driven grouse shooting is defined as where shooters sit in lines of grouse butts on open moorland, and red grouse are then driven by beaters and dogs over the guns to shoot. The activity usually involves shooting large grouse “bags” (where large numbers of grouse are shot in a day). It is a unique hunting type to the UK (mainly England and Scotland) and shooters will pay large sums of money for a day’s shooting. Typically, gamekeepers are employed to kill predators that eat grouse; heather is burned to create young heather (the main foodplant of red grouse); and other additional management techniques are employed to produce as many red grouse as possible for shooting. The red grouse shooting season opens on the 12 August (“the Glorious Twelfth”). The alternative walked up grouse shooting involves a small number of shooters accompanied by dogs. They generally take small and sustainable numbers of grouse, as walked up shooting is more about the hunting experience. This is much less of a conservation issue for us. -

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

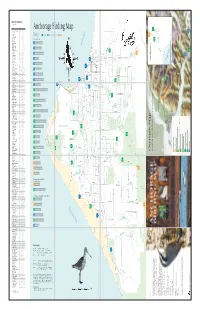

Anchorage Birding Map ❏ Common Redpoll* C C C C ❄ ❏ Hoary Redpoll R ❄ ❏ Pine Siskin* U U U U ❄ Additional References: Anchorage Audubon Society

BIRDS OF ANCHORAGE (Knik River to Portage) SPECIES SP S F W ❏ Greater White-fronted Goose U R ❏ Snow Goose U ❏ Cackling Goose R ? ❏ Canada Goose* C C C ❄ ❏ Trumpeter Swan* U r U ❏ Tundra Swan C U ❏ Gadwall* U R U ❄ ❏ Eurasian Wigeon R ❏ American Wigeon* C C C ❄ ❏ Mallard* C C C C ❄ ❏ Blue-winged Teal r r ❏ Northern Shoveler* C C C ❏ Northern Pintail* C C C r ❄ ❏ Green-winged Teal* C C C ❄ ❏ Canvasback* U U U ❏ Redhead U R R ❄ ❏ Ring-necked Duck* U U U ❄ ❏ Greater Scaup* C C C ❄ ❏ Lesser Scaup* U U U ❄ ❏ Harlequin Duck* R R R ❄ ❏ Surf Scoter R R ❏ White-winged Scoter R U ❏ Black Scoter R ❏ Long-tailed Duck* R R ❏ Bufflehead U U ❄ ❏ Common Goldeneye* C U C U ❄ ❏ Barrow’s Goldeneye* U U U U ❄ ❏ Common Merganser* c R U U ❄ ❏ Red-breasted Merganser u R ❄ ❏ Spruce Grouse* U U U U ❄ ❏ Willow Ptarmigan* C U U c ❄ ❏ Rock Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ White-tailed Ptarmigan* R R R R ❄ ❏ Red-throated Loon* R R R ❏ Pacific Loon* U U U ❏ Common Loon* U R U ❏ Horned Grebe* U U C ❏ Red-necked Grebe* C C C ❏ Great Blue Heron r r ❄ ❏ Osprey* R r R ❏ Bald Eagle* C U U U ❄ ❏ Northern Harrier* C U U ❏ Sharp-shinned Hawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Northern Goshawk* U U U R ❄ ❏ Red-tailed Hawk* U R U ❏ Rough-legged Hawk U R ❏ Golden Eagle* U R U ❄ ❏ American Kestrel* R R ❏ Merlin* U U U R ❄ ❏ Gyrfalcon* R ❄ ❏ Peregrine Falcon R R ❄ ❏ Sandhill Crane* C u U ❏ Black-bellied Plover R R ❏ American Golden-Plover r r ❏ Pacific Golden-Plover r r ❏ Semipalmated Plover* C C C ❏ Killdeer* R R R ❏ Spotted Sandpiper* C C C ❏ Solitary Sandpiper* u U U ❏ Wandering Tattler* u R R ❏ Greater Yellowlegs* -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Europe's Huntable Birds a Review of Status and Conservation Priorities

FACE - EUROPEAN FEDERATIONEurope’s FOR Huntable HUNTING Birds A Review AND CONSERVATIONof Status and Conservation Priorities Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities December 2020 1 European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE) Established in 1977, FACE represents the interests of Europe’s 7 million hunters, as an international non-profit-making non-governmental organisation. Its members are comprised of the national hunters’ associations from 37 European countries including the EU-27. FACE upholds the principle of sustainable use and in this regard its members have a deep interest in the conservation and improvement of the quality of the European environment. See: www.face.eu Reference Sibille S., Griffin, C. and Scallan, D. (2020) Europe’s Huntable Birds: A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities. European Federation for Hunting and Conservation (FACE). https://www.face.eu/ 2 Europe’s Huntable Birds A Review of Status and Conservation Priorities Executive summary Context Non-Annex species show the highest proportion of ‘secure’ status and the lowest of ‘threatened’ status. Taking all wild birds into account, The EU State of Nature report (2020) provides results of the national the situation has deteriorated from the 2008-2012 to the 2013-2018 reporting under the Birds and Habitats directives (2013 to 2018), and a assessments. wider assessment of Europe’s biodiversity. For FACE, the findings are of key importance as they provide a timely health check on the status of In the State of Nature report (2020), ‘agriculture’ is the most frequently huntable birds listed in Annex II of the Birds Directive. -

North American Game Birds Or Animals

North American Game Birds & Game Animals LARGE GAME Bear: Black Bear, Brown Bear, Grizzly Bear, Polar Bear Goat: bezoar goat, ibex, mountain goat, Rocky Mountain goat Bison, Wood Bison Moose, including Shiras Moose Caribou: Barren Ground Caribou, Dolphin Caribou, Union Caribou, Muskox Woodland Caribou Pronghorn Mountain Lion Sheep: Barbary Sheep, Bighorn Deer: Axis Deer, Black-tailed Deer, Sheep, California Bighorn Sheep, Chital, Columbian Black-tailed Deer, Dall’s Sheep, Desert Bighorn Mule Deer, White-tailed Deer Sheep, Lanai Mouflon Sheep, Nelson Bighorn Sheep, Rocky Elk: Rocky Mountain Elk, Tule Elk Mountain Bighorn Sheep, Stone Sheep, Thinhorn Mountain Sheep Gemsbok SMALL GAME Armadillo Marmot, including Alaska marmot, groundhog, hoary marmot, Badger woodchuck Beaver Marten, including American marten and pine marten Bobcat Mink North American Civet Cat/Ring- tailed Cat, Spotted Skunk Mole Coyote Mouse Ferret, feral ferret Muskrat Fisher Nutria Fox: arctic fox, gray fox, red fox, swift Opossum fox Pig: feral swine, javelina, wild boar, Lynx wild hogs, wild pigs Pika Skunk, including Striped Skunk Porcupine and Spotted Skunk Prairie Dog: Black-tailed Prairie Squirrel: Abert’s Squirrel, Black Dogs, Gunnison’s Prairie Dogs, Squirrel, Columbian Ground White-tailed Prairie Dogs Squirrel, Gray Squirrel, Flying Squirrel, Fox Squirrel, Ground Rabbit & Hare: Arctic Hare, Black- Squirrel, Pine Squirrel, Red Squirrel, tailed Jackrabbit, Cottontail Rabbit, Richardson’s Ground Squirrel, Tree Belgian Hare, European -

RED GROUSE and Birds of Prey

RED GROUSE and birds of prey This leaflet is supported ● by 17 voluntary bodies and addresses Illegal killing of birds of prey is limiting the concerns about the impact of predation population and distribution of several of red grouse by birds of prey (raptors). It species. explains how serious habitat loss and degradation have caused ● Management for grouse has helped to long-term declines in grouse bags, and how a high density of birds protect heather moors from forestry of prey can affect bags when grouse densities are low. It details plantations and livestock production, but why killing of birds of prey, illegally or under licence, and setting heavy grazing by sheep and deer is the quotas for birds of prey are not acceptable. It identifies measures main cause of declines in grouse bags. that can be taken to reduce the impact of predation on grouse and ● enhance heather moors for wildlife. ‘It is extremely unlikely that raptors were responsible for either the long-term decline or the fluctuations in grouse bags.’ Joint The concerns Raptor Study, Langholm.11 Conservation groups and the Government are ● ‘The raptor issue should be put on one side concerned because widespread killing of birds of because it is a diversion that has too often prey, especially on upland moorlands managed for resulted in managers taking their eyes off driven grouse-shooting, limits the population and the ball.’ The Heather Trust.25 distribution of several species. Killing birds of prey is ● Habitat management is fundamental to a a criminal activity involving hundreds of birds every long-term recovery of upland wildlife and year; for example: grouse shooting. -

Your Essential Guide to Grouse Shooting and Moorland Management

Your essential guide to grouse shooting and moorland management Who we are The Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) is a research and education charity conducting conservation science to enhance the British countryside for public benefit. For over 80 years we have been researching and developing game and wildlife management techniques and have had 135 scientific papers published in peer-reviewed journals on issues relating to upland ecology over the past 46 years. On the basis of our scientific expertise and credibility, we regularly provide advice to such statutory bodies as Defra, Scottish Natural Heritage and Natural England. We also provide practical advice to farmers and landowners on how to manage their land with a view to improving biodiversity. Much of our research is undertaken in collaboration with other institutions and organisations, including the following: Exeter, Imperial College London, Newcastle and Aberdeen Universities, the British Trust for Ornithology, the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the RSPB. To help disseminate this knowledge, representatives of the GWCT sat on over 100 external committees in 2015, including the following: Defra’s Upland Stakeholder Forum, Natural England’s main board and the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Panel. Why we support grouse moor management After spending 46 years researching and advising in the uplands we support grouse moor management for three primary reasons: 1. The habitat management undertaken on grouse moors preserves and enhances heather dominated habitats1. 2. The package of management, notably habitat enhancement along with predator control contributes to the conservation of a suite of upland bird species including upland waders2–4. -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

Revision of Molt and Plumage

The Auk 124(2):ART–XXX, 2007 © The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2007. Printed in USA. REVISION OF MOLT AND PLUMAGE TERMINOLOGY IN PTARMIGAN (PHASIANIDAE: LAGOPUS SPP.) BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY CONSIDERATIONS Peter Pyle1 The Institute for Bird Populations, P.O. Box 1346, Point Reyes Station, California 94956, USA Abstract.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt. A spring contour molt was signifi cantly later and more extensive in females than in males, a summer contour molt was signifi cantly earlier and more extensive in males than in females, and complete summer–fall wing and contour molts were statistically similar in timing between the sexes. Completeness of feather replacement, similarities between the sexes, and comparison of molts with those of related taxa indicate that the white winter plumage of ptarmigan should be considered the basic plumage, with shi s in hormonal and endocrinological cycles explaining diff erences in plumage coloration compared with those of other phasianids. Assignment of prealternate and pre- supplemental molts in ptarmigan necessitates the examination of molt evolution in Galloanseres. Using comparisons with Anserinae and Anatinae, I considered a novel interpretation: that molts in ptarmigan have evolved separately within each sex, and that the presupplemental and prealternate molts show sex-specifi c sequences within the defi nitive molt cycle. Received 13 June 2005, accepted 7 April 2006. Key words: evolution, Lagopus, molt, nomenclature, plumage, ptarmigan. Revision of Molt and Plumage Terminology in Ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.) Based on Evolutionary Considerations Rese.—By examining specimens of ptarmigan (Phasianidae: Lagopus spp.), I quantifi ed three discrete periods of molt and three plumages for each sex, confi rming the presence of a defi nitive presupplemental molt.