RED GROUSE and Birds of Prey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017)

Contents Scottish Birds 37:3 (2017) 194 President’s Foreword J. Main PAPERS 195 Potential occurrence of the Long-tailed Skua subspecies Stercorarius longicaudus pallescens in Scotland C.J. McInerny & R.Y. McGowan 202 Amendments to The Scottish List: species and subspecies The Scottish Birds Records Committee 205 The status of the Pink-footed Goose at Cameron Reservoir, Fife from 1991/92 to 2015/16: the importance of regular monitoring A.W. Brown 216 Montagu’s Harrier breeding in Scotland - some observations on the historical records from the 1950s in Perthshire R.L. McMillan SHORT NOTES 221 Scotland’s Bean Geese and the spring 2017 migration C. Mitchell, L. Griffin, A. MacIver & B. Minshull 224 Scoters in Fife N. Elkins OBITUARIES 226 Sandy Anderson (1927–2017) A. Duncan & M. Gorman 227 Lance Leonard Joseph Vick (1938–2017) I. Andrews, J. Ballantyne & K. Bowler ARTICLES, NEWS & VIEWS 229 The conservation impacts of intensifying grouse moor management P.S. Thompson & J.D. Wilson 236 NEWS AND NOTICES 241 Memories of the three St Kilda visitors in July 1956 D.I.M. Wallace, D.G. Andrew & D. Wilson 244 Where have all the Merlins gone? A lament for the Lammermuirs A.W. Barker, I.R. Poxton & A. Heavisides 251 Gannets at St Abb’s Head and Bass Rock J. Cleaver 254 BOOK REVIEWS 256 RINGERS' ROUNDUP Iain Livingstone 261 The identification of an interesting Richard’s Pipit on Fair Isle in June 2016 I.J. Andrews 266 ‘Canada Geese’ from Canada: do we see vagrants of wild birds in Scotland? J. Steele & J. -

Driven Grouse Shooting

Driven grouse shooting RSPB Council updated our previous policy on driven grouse shooting in October 2020. Our policy is to support licensing of driven grouse shooting across the UK, following expected progress on this issue in Scotland in 2020. Unless substantial progress (including effective licensing, stopping raptor killing, cessation of burning on peat soils, and banning use of lead ammunition) is made in reforming driven grouse shooting by 2025 in line with RSPB principles for sustainable gamebird shooting, we will consequently call on governments to introduce a specific ban on driven grouse shooting. Background Driven grouse shooting is defined as where shooters sit in lines of grouse butts on open moorland, and red grouse are then driven by beaters and dogs over the guns to shoot. The activity usually involves shooting large grouse “bags” (where large numbers of grouse are shot in a day). It is a unique hunting type to the UK (mainly England and Scotland) and shooters will pay large sums of money for a day’s shooting. Typically, gamekeepers are employed to kill predators that eat grouse; heather is burned to create young heather (the main foodplant of red grouse); and other additional management techniques are employed to produce as many red grouse as possible for shooting. The red grouse shooting season opens on the 12 August (“the Glorious Twelfth”). The alternative walked up grouse shooting involves a small number of shooters accompanied by dogs. They generally take small and sustainable numbers of grouse, as walked up shooting is more about the hunting experience. This is much less of a conservation issue for us. -

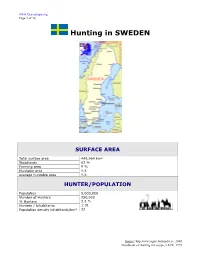

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

Review of Illegal Killing and Taking of Birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus

Review of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus Overview of main outputs of the project The information collated and analysed during this project has been summarised in a variety of outputs: 1. This full report Presenting all the aspects of the project at regional and national levels http://www.birdlife.org/illegal-killing 2. Scientific paper Presenting results of the regional assessment of scope and scale of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus1 https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/bird-conservation-international 3. Legislation country factsheets Presenting a review of national legislation on hunting, trapping and trading of birds in each assessed country http://www.birdlife.org/datazone/country (under ‘resources’ tab) 4. ‘The Killing 2.0’ Layman’s report Short communications publication for publicity purposes with some key headlines of the results of the project and the previous one focussing on the Mediterranean region http://www.birdlife.org/illegal-killing Credits of front cover pictures 1 2 3 4 1 Hen harrier Circus cyaneus © RSPB 2 Illegal trapping of Hen Harrier in the UK © RSPB 3 Common Coot (Fulica atra) © MISIK 4 Illegal trade of waterbirds illegally killed in Azerbaijan © AOS Citation of the report BirdLife International (2017) Review of illegal killing and taking of birds in Northern and Central Europe and the Caucasus. Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International. 1 Paper in revision process for publication in Bird Conservation International in October 2017 when this report is released 1 Executive Summary The illegal killing and taking of wild birds remains a major threat on a global scale. -

The Effects of Upland Management Practices on Avian Diversity

The Effects of Upland Management Practices on Avian diversity Bronwen Daniel September 2010 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science and the Diploma of Imperial College London 1 Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................. 3 2. Background................................................................................................................................. 11 2.1 Birds as indicators ................................................................................................................ 11 2.1.1 Upland birds ...................................................................................................................... 11 2.2 Management Practices......................................................................................................... 13 2.2.1 Grouse Moor Management........................................................................................... 15 2.2.2 Predator control ............................................................................................................ 16 2.2.3 Burning .......................................................................................................................... 17 2.2.4 Grazing Pressure............................................................................................................ 17 2.2.5 Implications of upland management for bird populations .......................................... -

Your Essential Guide to Grouse Shooting and Moorland Management

Your essential guide to grouse shooting and moorland management Who we are The Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) is a research and education charity conducting conservation science to enhance the British countryside for public benefit. For over 80 years we have been researching and developing game and wildlife management techniques and have had 135 scientific papers published in peer-reviewed journals on issues relating to upland ecology over the past 46 years. On the basis of our scientific expertise and credibility, we regularly provide advice to such statutory bodies as Defra, Scottish Natural Heritage and Natural England. We also provide practical advice to farmers and landowners on how to manage their land with a view to improving biodiversity. Much of our research is undertaken in collaboration with other institutions and organisations, including the following: Exeter, Imperial College London, Newcastle and Aberdeen Universities, the British Trust for Ornithology, the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the RSPB. To help disseminate this knowledge, representatives of the GWCT sat on over 100 external committees in 2015, including the following: Defra’s Upland Stakeholder Forum, Natural England’s main board and the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Panel. Why we support grouse moor management After spending 46 years researching and advising in the uplands we support grouse moor management for three primary reasons: 1. The habitat management undertaken on grouse moors preserves and enhances heather dominated habitats1. 2. The package of management, notably habitat enhancement along with predator control contributes to the conservation of a suite of upland bird species including upland waders2–4. -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

Environmental Impacts of High-Output Driven Shooting of Red Grouse

Ibis (2016), 158, 446–452 Viewpoint ulating quarry species, hunting season and permitted hunting methods. There is no statutory requirement for hunters to report their bags, although records are col- lected by a non-profit organization, the Game & Wildlife Environmental impacts of Conservation Trust (GWCT). This combination of inten- sive shooting practice with weak regulation is almost high-output driven unique (Mustin et al. 2012), and offers general insights shooting of Red Grouse into the environmental impacts of intensive game man- agement when managers operate without much of the Lagopus lagopus scotica regulation recommended by Loveridge et al. (2009). PATRICK S. THOMPSON,1* DAVID J. T. DOUGLAS,2 There is growing public debate about these impacts DAVID G. HOCCOM,3 JEFF KNOTT,3 (Thompson et al. 2009, Avery 2015, Wightman & Tin- STAFFAN ROOS2 & JEREMY D. WILSON2 gay 2015), part of a wider trend of public engagement in 1RSPB, 1 Sirius House, Amethyst Road, hunting policy (Minnis 1998). For example, the recent Newcastle-upon-Tyne NE4 7YL, UK near-extirpation of the Hen Harrier Circus cyaneus as a 2RSPB Centre for Conservation Science, RSPB breeding bird in England (Redpath et al. 2010) and Scotland, 2 Lochside View, Edinburgh Park, claims of mass culls of Mountain Hares Lepus timidus in Edinburgh EH12 9DH, UK Scotland by grouse moor managers (Anon 2014) has 3RSPB, The Lodge, Sandy, Bedfordshire SG19 2DL, UK prompted three UK public petitions to license or ban dri- ven grouse shooting, one for the introduction of vicarious liability (whereby the rights-holder is held responsible for the actions of an employee) and one for stronger legal protection of Scottish Mountain Hares, collectively amassing over 85 000 signatures by 29 January 2016. -

Cecal Fermentation in Mallards in Relation to Diet

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 107 A change in tongue volume with body size could more efficient despite proportionally smaller volumes be accomplished in several ways. If larger birds had of the tongue grooves. longer tongues, volume could be increased by length- This study was supported by National Science ening. A change in volume could also result from a Foundation Grants GB-12344, GB-39940, GB-28956X, change in the dimensions of the grooves in tongues of GB-40108, and GB-19200. We give special thanks to the same length. This appears to be the case for N. the Gilgil Country Club, and especially Ray and Bar- verticalis as compared with N. venusta (fig. 3), bara Terry, for providing a pleasant environment. where tongues are the same length but the smaller venusta has a smaller tongue volume. For the larger LITERATURE CITED N. reichenowi, the greater volume is achieved by a EIILEK, J. M. 1968. Optimal choice in animals. slightly longer tongue with much larger grooves (fig. Am. Nat. 102:385-389. 3). HAISSWORTH, F. R. 1973. On the tongue of a hum- Bill length and morphology appear to be well cor- mingbird: Its role in the rate and energetics of related with corolla length and morphology in nectar- feeding. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 46:65-78. feeding birds (Snow and Snow 1972, Wolf et al. HAINSWORTH, F. R., ANU L. L. WOLF. 1972a. Ener- unpubl. data). This co-evolutionary relationship pre- getics of nectar extraction in a small, high alti- sumably provides for ease in reaching and extracting tude, tropical hummingbird, Selusphorus Pam- nectar at the base of differently shaped flowers. -

Strongylosis Control in Red Grouse

Strongylosis control in red grouse Current best practice guidelines for the management of strongylosis in red grouse www.gct.org.uk Strongylosis and red grouse Introduction The cause of regular crashes in the numbers of red grouse has been of considerable interest for many years to those involved with grouse moor management.The presence of Trichostrongylus tenuis, a parasitic strongyle or threadworm which lives in the gut of red grouse, has been recorded in the literature for more than 100 years. The disease it causes is often referred to as strongylosis. The biology of the parasite and its relationship with the host have been studied in detail. Research has established that the strongyle worm can cause regular and large- scale reductions in the numbers of grouse and the parasite control can be effective in reducing the losses of grouse to disease. To reduce the severity of these population crashes, parasite control is practised on many moors.The Game Conservancy Trust has been conducting research into direct parasite control methods within red grouse since the early 1980s and this pamphlet sets out this knowledge and best practice guidelines for parasite control that are currently available. (Laurie Campbell) 2 Biology and life-cyle of Trichostrongylus tenuis Adult strongyle worms live in the blind-ended part of the gut known as the caeca, which are long, paired tubes. Red grouse have long caeca averaging 70cm, the length being an adaptation to extract nutrients from their poor fibrous diet.This threadworm has a relatively simple life-cycle.The worms mate within the grouse caeca, where each female worm can produce around 110 eggs a day.These eggs are passed out with the caecal droppings. -

Chapter on Grouse Shooting

The Moorland Balance 1. Grouse Shooting Grouse shooting in the UK occurs in two main forms: driven shooting and walked-up, often over dogs. Driven shooting typically requires higher grouse densities, and this needs more eective management. The scale and impact of this management is the issue which provokes much of the debate around grouse shooting. This chapter describes grouse shooting and introduces the management techniques used. Left: © Tarquin Millington-Drake; Above: © Matt Limb Above: Millington-Drake; Tarquin © Left: 1 Grouse Shooting What are grouse and where are they found? There are four species of grouse in Britain: red grouse, black grouse, capercaillie and ptarmigan. The red grouse population is estimated to be 230,000 pairs1, and it is one of this country’s few endemic sub-species, meaning that they are only found in the British Isles. They inhabit heather moorland including areas of both blanket bog and upland heath. The black grouse population is estimated to be 5,100 males UK- wide1. They are found on the moorland fringe and use hill-edge woodlands of both conifer and deciduous species. There are fewer than 2,000 capercaillie in a handful of pine-dominated Scottish woodlands1. Ptarmigan live above 800m and like capercaillie are also only found in Scotland. Grouse populations tend to fluctuate in size over the years and in relation to management, so these figures are an estimate. Species Population Population UK conservation estimate status trend Red grouse 230,000 pairs Fluctuating Amber listed Black grouse 5,100 males Severe decline Red listed Capercaillie 1,300 individuals Severe decline Red listed (800-1,900) Ptarmigan 2,000-15,000 pairs Unknown Green listed (range stable) The number and trends of grouse species in the UK, based on figures from Birds of Conservation Concern 42, Population estimates of birds in Great Britain and the UK¦ and Birdlife International’s Datazone.