Strongylosis Control in Red Grouse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Driven Grouse Shooting

Driven grouse shooting RSPB Council updated our previous policy on driven grouse shooting in October 2020. Our policy is to support licensing of driven grouse shooting across the UK, following expected progress on this issue in Scotland in 2020. Unless substantial progress (including effective licensing, stopping raptor killing, cessation of burning on peat soils, and banning use of lead ammunition) is made in reforming driven grouse shooting by 2025 in line with RSPB principles for sustainable gamebird shooting, we will consequently call on governments to introduce a specific ban on driven grouse shooting. Background Driven grouse shooting is defined as where shooters sit in lines of grouse butts on open moorland, and red grouse are then driven by beaters and dogs over the guns to shoot. The activity usually involves shooting large grouse “bags” (where large numbers of grouse are shot in a day). It is a unique hunting type to the UK (mainly England and Scotland) and shooters will pay large sums of money for a day’s shooting. Typically, gamekeepers are employed to kill predators that eat grouse; heather is burned to create young heather (the main foodplant of red grouse); and other additional management techniques are employed to produce as many red grouse as possible for shooting. The red grouse shooting season opens on the 12 August (“the Glorious Twelfth”). The alternative walked up grouse shooting involves a small number of shooters accompanied by dogs. They generally take small and sustainable numbers of grouse, as walked up shooting is more about the hunting experience. This is much less of a conservation issue for us. -

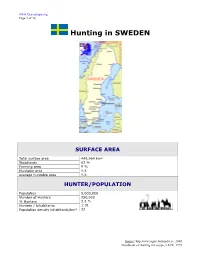

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Paul Johnsgard Collection Papers in the Biological Sciences 1983 Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants Paul A. Johnsgard University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard Part of the Ornithology Commons Johnsgard, Paul A., "Hybridization & Zoogeographic Patterns in Pheasants" (1983). Paul Johnsgard Collection. 17. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/johnsgard/17 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Papers in the Biological Sciences at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Paul Johnsgard Collection by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. HYBRIDIZATION & ZOOGEOGRAPHIC PATTERNS IN PHEASANTS PAUL A. JOHNSGARD The purpose of this paper is to infonn members of the W.P.A. of an unusual scientific use of the extent and significance of hybridization among pheasants (tribe Phasianini in the proposed classification of Johnsgard~ 1973). This has occasionally occurred naturally, as for example between such locally sympatric species pairs as the kalij (Lophura leucol11elana) and the silver pheasant (L. nycthelnera), but usually occurs "'accidentally" in captive birds, especially in the absence of conspecific mates. Rarely has it been specifically planned for scientific purposes, such as for obtaining genetic, morphological, or biochemical information on hybrid haemoglobins (Brush. 1967), trans ferins (Crozier, 1967), or immunoelectrophoretic comparisons of blood sera (Sato, Ishi and HiraI, 1967). The literature has been summarized by Gray (1958), Delacour (1977), and Rutgers and Norris (1970). Some of these alleged hybrids, especially those not involving other Galliformes, were inadequately doculnented, and in a few cases such as a supposed hybrid between domestic fowl (Gallus gal/us) and the lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) can be discounted. -

RED GROUSE and Birds of Prey

RED GROUSE and birds of prey This leaflet is supported ● by 17 voluntary bodies and addresses Illegal killing of birds of prey is limiting the concerns about the impact of predation population and distribution of several of red grouse by birds of prey (raptors). It species. explains how serious habitat loss and degradation have caused ● Management for grouse has helped to long-term declines in grouse bags, and how a high density of birds protect heather moors from forestry of prey can affect bags when grouse densities are low. It details plantations and livestock production, but why killing of birds of prey, illegally or under licence, and setting heavy grazing by sheep and deer is the quotas for birds of prey are not acceptable. It identifies measures main cause of declines in grouse bags. that can be taken to reduce the impact of predation on grouse and ● enhance heather moors for wildlife. ‘It is extremely unlikely that raptors were responsible for either the long-term decline or the fluctuations in grouse bags.’ Joint The concerns Raptor Study, Langholm.11 Conservation groups and the Government are ● ‘The raptor issue should be put on one side concerned because widespread killing of birds of because it is a diversion that has too often prey, especially on upland moorlands managed for resulted in managers taking their eyes off driven grouse-shooting, limits the population and the ball.’ The Heather Trust.25 distribution of several species. Killing birds of prey is ● Habitat management is fundamental to a a criminal activity involving hundreds of birds every long-term recovery of upland wildlife and year; for example: grouse shooting. -

Your Essential Guide to Grouse Shooting and Moorland Management

Your essential guide to grouse shooting and moorland management Who we are The Game & Wildlife Conservation Trust (GWCT) is a research and education charity conducting conservation science to enhance the British countryside for public benefit. For over 80 years we have been researching and developing game and wildlife management techniques and have had 135 scientific papers published in peer-reviewed journals on issues relating to upland ecology over the past 46 years. On the basis of our scientific expertise and credibility, we regularly provide advice to such statutory bodies as Defra, Scottish Natural Heritage and Natural England. We also provide practical advice to farmers and landowners on how to manage their land with a view to improving biodiversity. Much of our research is undertaken in collaboration with other institutions and organisations, including the following: Exeter, Imperial College London, Newcastle and Aberdeen Universities, the British Trust for Ornithology, the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology and the RSPB. To help disseminate this knowledge, representatives of the GWCT sat on over 100 external committees in 2015, including the following: Defra’s Upland Stakeholder Forum, Natural England’s main board and the UK Birds of Conservation Concern Panel. Why we support grouse moor management After spending 46 years researching and advising in the uplands we support grouse moor management for three primary reasons: 1. The habitat management undertaken on grouse moors preserves and enhances heather dominated habitats1. 2. The package of management, notably habitat enhancement along with predator control contributes to the conservation of a suite of upland bird species including upland waders2–4. -

Species Included in Categories A, B & C Scientific

Species included in categories A, B & C Scientific name Race Category 1 Mute Swan Cygnus olor -- A / C1 2 Bewick’s Swan Cygnus columbianus bewickii A >> Tundra Swan columbianus -- 3 Whooper Swan Cygnus cygnus -- A 4 Bean Goose Anser fabalis fabilis A >> Tundra Bean Goose rossicus -- 5 Pink-footed Goose Anser brachyrhynchus -- A 6 White-fronted Goose Anser albifrons flavirostris A >> Russian White-fronted Goose albifrons -- 7 Lesser White-fronted Goose Anser erythropus -- A 8 Greylag Goose Anser anser anser A / C1 9 Snow Goose Anser caerulescens caerulescens A / D1 >> Greater Snow Goose atlanticus -- 10 Cackling Goose Branta hutchinsii hutchinsii A 11 Canada Goose Branta canadensis canadensis A / C1 >> Todd's Canada Goose interior -- 12 Barnacle Goose Branta leucopsis -- A / C1 13 Brent Goose Branta bernicla hrota A >> Dark-bellied Brent Goose bernicla -- >> Black Brant nigricans -- 14 Ruddy Shelduck Tadorna ferruginea -- B / D1 15 Shelduck Tadorna tadorna -- A 16 Mandarin Duck Aix galericulata -- C1 17 Wigeon Anas penelope -- A 18 American Wigeon Anas americana -- A 19 Gadwall Anas strepera -- A 20 Baikal Teal Anas formosa -- A / D1 21 Teal Anas crecca crecca A 22 Green-winged Teal Anas carolinensis -- A 23 Mallard Anas platyrhynchos platyrhynchos A / C1 24 American Black Duck Anas rubripes -- A 25 Pintail Anas acuta acuta A 26 Garganey Anas querquedula -- A 27 Blue-winged Teal Anas discors -- A 28 Shoveler Anas clypeata -- A 29 Red-crested Pochard Netta rufina -- A 30 Pochard Aythya ferina -- A 31 Redhead Aythya americana -- A 32 Ring-necked -

Cecal Fermentation in Mallards in Relation to Diet

SHORT COMMUNICATIONS 107 A change in tongue volume with body size could more efficient despite proportionally smaller volumes be accomplished in several ways. If larger birds had of the tongue grooves. longer tongues, volume could be increased by length- This study was supported by National Science ening. A change in volume could also result from a Foundation Grants GB-12344, GB-39940, GB-28956X, change in the dimensions of the grooves in tongues of GB-40108, and GB-19200. We give special thanks to the same length. This appears to be the case for N. the Gilgil Country Club, and especially Ray and Bar- verticalis as compared with N. venusta (fig. 3), bara Terry, for providing a pleasant environment. where tongues are the same length but the smaller venusta has a smaller tongue volume. For the larger LITERATURE CITED N. reichenowi, the greater volume is achieved by a EIILEK, J. M. 1968. Optimal choice in animals. slightly longer tongue with much larger grooves (fig. Am. Nat. 102:385-389. 3). HAISSWORTH, F. R. 1973. On the tongue of a hum- Bill length and morphology appear to be well cor- mingbird: Its role in the rate and energetics of related with corolla length and morphology in nectar- feeding. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. 46:65-78. feeding birds (Snow and Snow 1972, Wolf et al. HAINSWORTH, F. R., ANU L. L. WOLF. 1972a. Ener- unpubl. data). This co-evolutionary relationship pre- getics of nectar extraction in a small, high alti- sumably provides for ease in reaching and extracting tude, tropical hummingbird, Selusphorus Pam- nectar at the base of differently shaped flowers. -

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: United Kingdom

Summary of National Hunting Regulations: United Kingdom Updated in October 2016 HUNTING AND TRAPPING LEGISLATION/ RESOURCES Name of main legislation: In the UK hunting law is a national issue, therefore several hunting laws exist: Wildlife and Countryside Act 1981 for England, Scotland and Wales; Wildlife (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 Year of publication: see above Supporting legislation: Legislation updates: In England and Wales the law has been amended by the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 and in Scotland by the Nature Conservation (Scotland) Act 2004. Hunting legislation (web link): http://www.legislation.gov.uk/browse Authority in charge of controlling hunting (web link): Home Office (Police) UK National Wildlife Crime Unit http://www.nwcu.police.uk/ Major inconsistencies or loopholes detected (if yes please describe): The UK lacks a system of licensing for hunting, with no statutory limits applied to hunting bags, or statutory requirement to submit returns. Questions have been raised about consequences for the UK’s compliance with principles under Article 7 of the Birds Directive, including “wise use”, “ecologically balanced control” and requirement not to “jeopardise conservation efforts” for huntable or non- huntable species. The lack of a licensing system also limits the capacity of authorities to apply restrictions on hunting in response to incidents of wildlife crime. Note: the devolved Scottish Government have commissioned a review of game licensing systems in Europe, which is expected to report this year. Derogations (on EU Birds Directive and/or Bern Convention): None HUNTING AND TRAPPING: METHODS AND RESTRICTIONS Legal methods/restrictions Notes - Certain game bird species can be hunt during the open shooting season (see below) - There is no requirement to hold a hunting licence. -

Sustainable Driven Grouse Shooting?

Sustainable Driven Grouse Shooting? A summary of the evidence Authors Professor Simon Denny, BA, MA, PhD Dr Tracey Latham-Green, BA, MBA, PhD Professor Richard Hazenberg BA, MA, PhD Independent chair Professor James Crabbe, Wolfson College, University of Oxford July 2021 1 Date Version Updates 18.07.2021 1.0 First edition 2 CONTENTS FOREWORD BY THE INDEPENDENT CHAIR 7 1 INTRODUCTION 9 1.1 AIM OF THE REPORT 9 1.2 RELEVANCE AND AUDIENCE 9 1.3 THE LOGIC OF OPPOSITION TO DRIVEN GROUSE SHOOTING 10 1.4 ABOUT THE AUTHORS 12 1.5 INDEPENDENT REVIEW 13 2 SYNOPSIS 14 2.1 ECONOMICS 14 2.1.1 ECONOMIC IMPACT 1 14 2.1.2 ECONOMIC IMPACT 2 15 2.1.3 ECONOMIC IMPACT 3 16 2.1.4 ECONOMIC IMPACT 4 16 2.1.5 ECONOMIC IMPACT 5 17 2.1.6 ECONOMIC IMPACT 6 17 2.2 BIODIVERSITY 18 2.2.1 INTRODUCTION 18 2.2.2 IMPACT OF POLICY DECISIONS 19 2.2.3 RENEWABLE ENERGY 19 2.2.4 TOURISM 20 2.2.5 INTEGRATED MOORLAND MANAGEMENT 20 2.2.6 PREDATOR CONTROL 20 2.2.7 MOUNTAIN HARES 21 2.2.8 BIRDS 21 2.2.9 INVERTEBRATES 22 2.2.10 TICKS 22 2.2.11 MEDICATED GRIT 22 2.2.12 HEATHER BEETLE 23 2.2.13 STAKEHOLDERS 23 2.3 NATURAL CAPITAL AND ECOSYSTEMS 24 2.3.1 INTRODUCTION 24 2.3.2 DEFINITIONAL ISSUES 25 2.3.3 FIRE 25 2.3.4 BURNING VS. MOWING 28 2.3.5 WATER 28 2.4 SOCIAL IMPACTS 29 2.5 ALTERNATIVE USES 32 2.6 OPPOSITION TO DGS: MOTIVATIONS AND METHODS 36 3 METHODOLOGY 40 4 OVERVIEW OF DRIVEN GROUSE SHOOTING 41 4.1 THE RED GROUSE: AN INTRODUCTION 41 4.1.1 INTRODUCTION 41 4.1.2 DIFFERENT SPECIES OF GROUSE 41 4.1.3 THE RED GROUSE 42 3 4.1.4 HABITAT AND DISTRIBUTION 43 4.1.5 DISEASES 44 4.1.6 -

First-Winter Plumages in the Galliformes

Vol.194s 62]I P•JD•S,Plumages in the Galliformes 223 FIRST-WINTER PLUMAGES IN THE GALLIFORMES BY GEORGE A. PETRIDES AS is well known, the typical post-juvenal wing of the Galliformes differs from that of most birds in that the outer two pairs of juvenal primaries are not replacedby adult remigesat the post-juvenalmolt but are carried until the secondautumn. In a recent investigation of age criteria for gallinaceousgame birds (Petrides, 1942), however, it was noted that this feature, which identifiesyoung of the year in most species,did not apply to all Galliformesand that considerablevaria- tion also occurred in the number of juvenal greater primary coverts retained. It was particularly noted that the pheasantsand European quails, which have been placed in the same subfamily in recent revi- sions of the order, undergo radically different types of post-juvenal molt. Intrigued by the findings for native and naturalized American species,a study of the entirely exotic forms was also planned, but time limitations and lack of suitable specimen material eventually permitted only a cursory investigation of these groups. Becauseit seemsquite unlikely that the project will be resumed,however, the limited findingsin these foreign groups are also presentedhere as a possibleaid to future investigators. Referenceto Table 1 will indicate the types of post-juvenalmolt in the several groups of the Galliformes; the more detailed notes beyond list the evidence(not always complete)upon which the table is based. Variation in the size of the outermost greater primary covert as de- scribed in the table may also be of taxonomic importance. -

Condition-Dependence, Colouration and Growth of Red Eye Combs in Black Grouse Lyrurus Tetrix

Condition-dependence, colouration and growth of red eye combs in black grouse Lyrurus tetrix Sarah Harris A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Lincoln for the degree of Masters of Science by research, supervised by Dr. Carl Soulsbury and Dr. Tom Pike This research programme was carried out in collaboration with the University of Jyväskylä, Finland February 2016 Table of Contents List of Figures and Tables .......................................................................................................... 4 Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Thesis Outline ................................................................................................................................ 8 Contributions ............................................................................................................................ 8 Publications and Conferences ............................................................................................... 9 Ethics ....................................................................................................................................... 10 Chapter 1: Introduction .............................................................................................................. 11 1.1 Sexual ornament expression ......................................................................................... 11 1.3 Research aims ................................................................................................................ -

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-List Species (Medium Conservation Concern)

Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Amber-list species (medium conservation concern) Breeding Breeding continued Wintering continued Goosander Swallow Smew Garganey Sand Martin Pintail Spotted Crake Willow Warbler Black-throated Diver European Storm-petrel Starling Great Northern Diver Fulmar Spotted Flycatcher Bittern Manx Shearwater Northern Wheatear Turnstone Gannet Goldcrest Brambling Shag House Sparrow Little Ringed Plover Tree Sparrow Breeding and Wintering Common Sandpiper Greenfinch Mute Swan Mediterranean Gull Linnet Whooper Swan Little Tern Pied Flycatcher Red-breasted Merganser Roseate Tern Western Yellow Wagtail Shelduck Common Tern Tufted Duck Arctic Tern Passage Gadwall Sandwich Tern Cory's Shearwater Wigeon Great Skua Ruff Mallard Black Guillemot Spotted Redshank Teal Common Guillemot Wood Sandpiper Great Crested Grebe Short-eared Owl Little Gull Coot Marsh Harrier Black Tern Red-throated Diver Hen Harrier Wryneck Cormorant Goshawk Tree Pipit Ringed Plover Kingfisher Black-headed Gull Merlin Wintering Common Gull Chough Brent Goose Lesser Black-backed Gull Skylark Barnacle Goose European Herring Gull Bearded Reedling Greylag Goose House Martin Greater White-fronted Goose For more information, please see Gilbert G, Stanbury A and Lewis L (2021), “Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020 –2026”. Irish Birds 43: 1–22 The categorisation of species as breeding, wintering etc. refers to the populations against which BoCCI criteria were applied Birds of Conservation Concern in Ireland 2020-2026 Red-list species