Wildlifemanagementin Europe Outsidethe Sovietunion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lowland Book 170618.Indd

Grey partridges are an “indicator species” for broader farmland biodiversity, because where they thrive, a range of other species tend to do well. © Markus Jenny 3. Grey partridge In the past, the wild grey partridge thrived on farmland, and was traditionally the main focus of shooting in the lowlands. Management for driven partridge shooting led to rising numbers during the 19th century; it involved comprehensive predator control in a farmed environment that provided good partridge habitat, with weedy cereal crops, traditional crop rotations including grass crops, small fields separated by hedges, fallows and waste ground. By contrast, grey partridge numbers have been falling in the UK throughout the second half of the 20th century, with the decline becoming most marked since the mid-1960s. To focus conservation efforts, the grey partridge was put on the UK Red Data List in 1990, became a priority species under the 1995 UK Biodiversity Action Plan36, and remains a red-listed Bird of Conservation Concern. Progress has been made in areas that make a commitment to partridge conservation, but overall the decline in their numbers continues. GWCT research on grey partridge declines in the 1960s and 1970s helped to establish the new field of agro-ecology, which is studying 38 39 The Knowledge ecology within farming systems. Scientific study moved from recording declines, to investigating the changes in the arable environment that were affecting partridges45–47. This work found that the causes of the grey partridge decline were directly or indirectly related to much wider declines in many aspects of farmland biodiversity. For instance, the UK government monitors national bird abundance through the British Trust for Ornithology’s Breeding Bird Survey, which has shown a 92% decline in numbers of grey partridge from 1967 to 2015, in conjunction with declines in many other species of farmland bird48. -

'Alae 'Ula (Hawaiian Moorhen)

NATIVE WATERBIRDS AVIAN NEWCOMERS These newly-created wetlands have been rapidly colonized by native waterbirds, Many non-native birds are attracted to the wetland restoration as well. The including four species that are highly endangered and found only in the Hawaiian long-necked white waders are Cattle Egrets, native to the Old World. Non-native Islands. The ‘Alae ‘Ula, or Hawaiian Moorhen (Gallinula chloropus sandvicensis), songbirds include the Common Myna, White-rumped Shama, two unrelated kinds of and Koloa Maoli, or Koloa Duck (Anas wyvilliana), have by now raised many broods cardinals, and three kinds of doves. Many of these exotic species probably became here, nesting among the native sedges. The Ae‘o, or Hawaiian Stilt (Himantopus established in recent decades as escaped cage birds. Before the accidental mexicanus knudseni), and the Nēnē, or Hawaiian Goose (Branta sandvicensis), stop introduction of mosquitoes in the 19th century and bird diseases they carry, by almost daily to rest and feed. In the morning and evening, watch for the ‘Auku‘u these coastal lowlands were home to native honeycreepers and other native or Black-crowned Night Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax). Long-distance migrants such songbirds, preserved abundantly in the fossil record of Makauwahi Cave. as the Kōlea or Pacific Golden Plover Pluvialis( fulva) stop to rest and often winter here, as part of their annual 10,000-mile migration from breeding grounds in the Arctic to wintering sites in the tropics. Bones of all these bird species occur as fossils in the sediment of adjacent Makauwahi Cave, showing that they have thrived here for thousands of years. -

Muskox Management Report Alaska Dept of Fish and Game Wildlife

Muskox Management Report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000 Mary V. Hicks, Editor Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation December 2001 ADF&G Please note that population and harvest data in this report are estimates and may be refined at a later date. If this report is used in its entirety, please reference as: Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2001. Muskox management report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000. M.V. Hicks, editor. Juneau, Alaska. If used in part, the reference would include the author’s name, unit number, and page numbers. Authors’ names can be found at the end of each unit section. Funded in part through Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration, Proj. 16, Grants W-27-2 and W-27-3. LOCATION 2 GAME MANAGEMENT UNIT: 18 (41,159 mi ) GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION: Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta BACKGROUND NUNIVAK ISLAND Muskoxen were once widely distributed in northern and western Alaska but were extirpated by the middle or late 1800s. In 1929, with the support of the Alaska Territorial Legislature, the US Congress initiated a program to reintroduce muskoxen in Alaska. Thirty-one muskoxen were introduced from Greenland to Nunivak Island in Unit 18 during 1935–1936, as a first step toward reintroducing this species to Alaska. The Nunivak Island population grew slowly until approximately 1958 and then began a period of rapid growth. The first hunting season was opened in 1975, and the population has since fluctuated between 400 and 750 animals, exhibiting considerable reproductive potential, even under heavy harvest regimes. -

Small Game Review “Issues and Concerns”

ONTARIO FEDERATION OF ANGLERS AND HUNTERS SMALL GAME REVIEW “ISSUES AND CONCERNS” PRELIMINARY INPUT FROM THE ONTARIO FEDERATION OF ANGLERS AND HUNTERS OCTOBER 2009 General and Preliminary O.F.A.H. Comments/Suggestions Purpose The purpose is to update and revise the small game hunting regulations and policies, under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, with the view to: • reflect changes in populations and/or harvest pressure to ensure sustainability; • address significant knowledge gaps where there is a conservation concern; • optimize the ecological, social, economic and recreational benefits that accrue through sustainable hunting of small game birds and mammals; • refine management directions and establish broad targets/objectives; and • manage and prevent human-wildlife conflicts. Scope of Review The review should include the conservation and management of provincial game birds, small game mammals, and furbearers that are also hunted (e.g. red fox, raccoon). At this time, small game species with current management plans/policy (i.e. wild turkey, wolves) need not be a focus within this review. The harvest management of migratory birds is primarily a federal mandate, but the review should consider recommendations for the improved management of migratory birds where there is a clear provincial interest and mandate to do so (e.g. woodcock, sandhill cranes). The harvest of snapping turtles and bullfrogs is regulated under the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Act, but are not considered “small game” for the purpose of this review. Falconry should be recognized as a small and growing method of small game hunting within Ontario; however, it should be mentioned that its regulation is reviewed regularly through the Provincial Falconry Advisory Committee, so it will not be included within this general review. -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

Free Download! the Trumpeter Swan

G3647 The Trumpeter Swan by Sumner Matteson, Scott Craven and Donna Compton Snow-white Trumpeter Swans present a truly spectac- Swans of the Midwest ular sight. With a wingspan of more than 7 feet and a rumpeter Swans, along with ducks and geese, belong height of about 4 feet, the Trumpeter Swan (Cygnus buc- to the avian Order Anseriformes, Family Anatidae. cinator) ranks as the largest native waterfowl species in T Trumpeters have broad, flat bills with fine tooth-like North America. serrations along the edges which allow them to strain Because the Trumpeter Swan disappeared as a breed- aquatic plants and water. The birds’ long necks and ing bird in the Midwest, several states have launched strong feet allow them to uproot plants in water up to 4 restoration programs to reintroduce it to the region. This feet deep. publication will provide you with background informa- Most Trumpeter Swans weigh 21–30 pounds, tion on the Trumpeter Swan’s status and life history, and although some males exceed the average weight. The on restoration efforts being conducted in the upper male is called a cob; the female is called a pen; and a swan Midwest. in its first year is called a cygnet or juve- nile. The Trumpeter is often con- fused with the far more common Tundra Swan (formerly Whistling Swan, Cygnus columbianus), the only other native swan found routinely in North America. Tundra Swans can be seen in the upper Trumpeter Swan Midwest only during spring and fall migration. You can distinguish between the two native species most accurately by listening to their calls. -

Wild Geese in Captivity by Bob Elgas Big Timber, Montana

Wild Geese in Captivity by Bob Elgas Big Timber, Montana Man has always been fascinated by, Wild geese were frequently depicted exists, and wild geese have become and has had a close association with, on ancient structures. Indeed, the increasingly popular with avicul wild geese. As a result of their ten- Swan goose of China, and the Greylag turists. dency to vocalize an objection to of Europe were domesticated eons Throughout the world there are nocturnal disturbances, the early ago, long before the dawn of written some 15 species of wild geese, with Romans utilized them as watchdogs.. history. Even today the fascination numerous sub-species, all of which are native to the northern hemi sphere. Interestingly, there are no true geese in the southern hemisphere. South America is represented by a specialized group known as sheld geese, while Africa and Australia are represented by a number of birds with goose-like characteristics. Sheld geese are actually modified ducks which, through the evolutionary process, have assumed goose-like similarities. One of the more obvious differences is the dimorphism of sexes characterized by sheldgeese males being of completely different plumage than females. In true geese, both sexes are alike. Although the birds from the southern hemisphere are interesting in their own right, the differences are so great that they can not be classified with the true geese. The geese of the northern hemi sphere are divided into two groups the genus Anset; which is representa tive of the true geese, and the genus A representative ofthe genus Anser is thispair ofEmperorgeese (Anser canagicus). -

THE ALEUTIAN CACKLING GOOSE in ARIZONA DAVID VANDER PLUYM, 2841 Mcculloch Blvd

THE ALEUTIAN CACKLING GOOSE IN ARIZONA DAVID VANDER PLUYM, 2841 McCulloch Blvd. N #1, Lake Havasu City, Arizona, 86403; [email protected] ABSTRACT: There is little published information about the occurrence of the Aleutian Cackling Goose (Branta hutchinsii leucopareia) in Arizona. Formerly listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, this subspecies has rebounded, leading to an increase in numbers occurring outside its core range, including Arizona. Since the first in 1975, at least 24 well-founded records for Arizona have accumulated, one supported by a specimen, two by band recoveries, and 20 by diagnostic photo- graphs. Since 2013 the Aleutian Cackling Goose has occurred in Arizona annually between November and February. It is most frequent along the Colorado River, but records extend as far east as Willcox, Cochise County. The taxonomy of the “white-cheeked” geese is complex and debated. Currently, most treatments list 11 or 12 taxa in this group, and Banks et al. (2004) split them into two species: the Cackling Goose (Branta hutchinsii) and the Canada Goose (B. canadensis). Taxonomists generally recognize four extant subspecies of the Cackling Goose: hutchinsii, taverneri, minima, and leucopareia (Aleutian Cackling Goose). The now extinct population formerly breeding in the Commander and Kuril islands in Russia and wintering south to Japan has been considered a separate subspecies, asiatica (Banks et al. 2004), or a western population of leucopareia (e.g., Baldassarre 2014, Reeber 2015). Birds discovered breeding on the Semidi Islands in 1979 and wintering in coastal Oregon are phenotypically interme- diate between other populations of leucopareia and taverneri (Hatch and Hatch 1983) and do differ genetically from other populations of leucopareia, but they likely represent distinct populations of leucopareia rather than a valid separate taxon (Pierson et al. -

Driven Grouse Shooting

Driven grouse shooting RSPB Council updated our previous policy on driven grouse shooting in October 2020. Our policy is to support licensing of driven grouse shooting across the UK, following expected progress on this issue in Scotland in 2020. Unless substantial progress (including effective licensing, stopping raptor killing, cessation of burning on peat soils, and banning use of lead ammunition) is made in reforming driven grouse shooting by 2025 in line with RSPB principles for sustainable gamebird shooting, we will consequently call on governments to introduce a specific ban on driven grouse shooting. Background Driven grouse shooting is defined as where shooters sit in lines of grouse butts on open moorland, and red grouse are then driven by beaters and dogs over the guns to shoot. The activity usually involves shooting large grouse “bags” (where large numbers of grouse are shot in a day). It is a unique hunting type to the UK (mainly England and Scotland) and shooters will pay large sums of money for a day’s shooting. Typically, gamekeepers are employed to kill predators that eat grouse; heather is burned to create young heather (the main foodplant of red grouse); and other additional management techniques are employed to produce as many red grouse as possible for shooting. The red grouse shooting season opens on the 12 August (“the Glorious Twelfth”). The alternative walked up grouse shooting involves a small number of shooters accompanied by dogs. They generally take small and sustainable numbers of grouse, as walked up shooting is more about the hunting experience. This is much less of a conservation issue for us. -

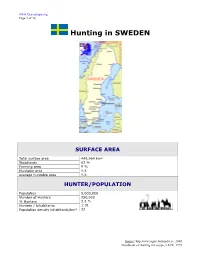

Hunting in SWEDEN

www.face-europe.org Page 1 of 14 Hunting in SWEDEN SURFACE AREA Total surface area 449,964 km² Woodlands 62 % Farming area 9 % Huntable area n.a. average huntable area n.a. HUNTER/POPULATION Population 9,000,000 Number of Hunters 290,000 % Hunters 3.2 % Hunters / Inhabitants 1:31 Population density inhabitants/km² 22 Source: http:www.jagareforbundet.se, 2005 Handbook of Hunting in Europe, FACE, 1995 www.face-europe.org Page 2 of 14 HUNTING SYSTEM Competent authorities The Parliament has overall responsibility for legislation. The Government - the Ministry of Agriculture - is responsible for questions concerning hunting. The Swedish Environmental Protection Agency is responsible for supervision and monitoring developments in hunting and game management. The County Administrations are responsible for hunting and game management questions on the county level, and are advised by County Game Committees - länsviltnämnd - with representatives of forestry, agriculture, hunting, recreational and environmental protection interests. } Ministry of Agriculture (Jordbruksdepartementet) S-10333 Stockholm Phone +46 (0) 8 405 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 64 96 } Swedish Environmental Protection Agency (Naturvårdsverket) SE-106 48 Stockholm Phone +46 (0)8 698 10 00 - Fax +46 (0)8 20 29 25 Hunters’ associations Hunting is a popular sport in Sweden. There are some 290.000 hunters, of whom almost 195.000 are affiliated to the Swedish Association for Hunting and Wildlife Management (Svenska Jägareförbundet). The association is a voluntary body whose main task is to look after the interests of hunting and hunters. The Parliament has delegated responsibility SAHWM for, among other things, practical game management work. -

What Makes a Good Alien? Dealing with the Problems of Non-Native Wildfowl Tony (A

What makes a good alien? Dealing with the problems of non-native wildfowl Tony (A. D.) Fox Mandarin Ducks Aix galericulata Richard Allen ABSTRACT Humans have been introducing species outside their native ranges as a source of food for thousands of years, but introductions of wildfowl have increased dramatically since the 1700s.The most serious consequence of this has been the extinction of endemic forms as a result of hybridisation, although competition between alien and native forms may also contribute to species loss. Globally, non-native wildfowl have yet to cause major disruption to ecosystem functions; introduce new diseases and parasites; cause anything other than local conflicts to agricultural and economic interests; or create major health and safety issues in ways that differ from native forms. The fact that this has not happened is probably simply the result of good fortune, however, since many introduced plants and animals have had huge consequences for ecosystems and human populations.The potential cost of greater environmental and economic damage, species extinction, and threats to the genetic and species diversity of native faunas means that we must do all we can to stop the deliberate or accidental introduction of species outside their natural range. International legislation to ensure this is remarkably good, but domestic law is generally weak, as is the political will to enforce such regulations.The case of the Ruddy Duck Oxyura jamaicensis in Europe will show whether control of a problem taxon can be achieved and underlines the financial consequences of dealing with introduced aliens.This paper was originally presented as the 58th Bernard Tucker Memorial Lecture to the Oxford Ornithological Society and the Ashmolean Natural History Society, in November 2008. -

Section E, Hoofed Animals

Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Caribou Muskox Section E-1 Section E-2 Moose Section E-3 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Nose and throat bots Hoofed Animals Hoofed Head Photo Credit: NWT Wildlife Division Caribou Section E-1.1 Lumpy jaw Contagious ecthyma Photo Credit: NWT Wildlife Division Caribou Section E-1.2 Photo Credit: GNWT Muskox Section E-2.1 Muskox Section E-2.2 Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Besnoitiosis Wildlife Division NWT Photo credit: Head Photo Credit: Susan Kutz Caribou Section E-1.11 Muskox Section E-2.6 Ticks Skin Moose Section E-3.1 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Warts Hoofed Animals Hoofed Skin Photo Credit: D. Campbell Caribou Section E-1.3 Moose Section E-3.2 Warbles Contagious ecthyma Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser Photo credit: Dr. Photo Credit: GNWT Caribou Section E-1.4 Muskox Section E-2.2 Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Besnoitiosis Wildlife Division NWT Photo credit: Photo Credit: Susan Kutz Caribou Section E-1.11 Muskox Section E-2.6 Skin Brucellosis Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser G. Photo credit: Dr. Caribou Section E-1.10 Muskox Section E-2.5 Moose Section E-3.6 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Liver tapeworm cyst Hoofed Animals Hoofed Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser Photo credit: Dr. Caribou Section E-1.5 Organs Moose Section E-3.3 Tapeworm cysts in the Lungs (Hydatid disease) Brucellosis Photo credit: Dr.