Developing an Angel Investor Forum to Complement an Engineering School's Entrepreneurship Initiatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding Sources for Entrepreneurs and Small Business

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding sources for entrepreneurs and small business. Introduction The Denver Office of Economic Development is pleased to release this fifth annual edition of the Denver Capital Matrix. This publication is designed as a tool to assist business owners and entrepreneurs with discovering the myriad of capital sources in and around the Mile High City. As a strategic initiative of the Denver Office of Economic Development’s JumpStart strategic plan, the Denver Capital Matrix provides a comprehensive directory of financing Definitions sources, from traditional bank lending, to venture capital firms, private Venture Capital – Venture capital is capital provided by investors to small businesses and start-up firms that demonstrate possible high- equity firms, angel investors, mezzanine sources and more. growth opportunities. Venture capital investments have a potential for considerable loss or profit and are generally designated for new and Small businesses provide the greatest opportunity for job creation speculative enterprises that seek to generate a return through a potential today. Yet, a lack of needed financing often prevents businesses from initial public offering or sale of the company. implementing expansion plans and adding payroll. Through this updated resource, we’re striving to help connect businesses to start-up Angel Investor – An angel investor is a high net worth individual active in and expansion capital so that they can thrive in Denver. venture financing, typically participating at an early stage of growth. Private Equity – Private equity is an individual or consortium of investors and funds that make investments directly into private companies or initiate buyouts of public companies. Private equity is ownership in private companies that is not listed or traded on public exchanges. -

Chronix Biomedical Secures $1.6 Million in Financing

Chronix Biomedical Secures $1.6 Million in Financing Led by Nation's Largest Angel Investor Network -- Keiretsu Forum LOS ANGELES, CA -- (MARKET WIRE) -- 05/24/2005 -- Keiretsu Forum, the nation's largest angel investor network, today announced its investment in Chronix Biomedical, an applied genomics company based in San Jose with research facilities in Göttingen, Germany. Chronix Biomedical has closed this round as a convertible note of $1.6 Million with Keiretsu Forum members investing $1.1 Million. The company develops products and services for the detection and monitoring of chronic diseases with particular focus on genomic-based assays that will be utilized in the emerging fields of "theranostics" and "pharmacogenetics." Chronix's first and second commercial products, the Göttingen Living Test (GLT) is a test for the detection of cows at risk for developing bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or mad cow disease and the humans' form of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD). Its third commercial product is a personalized medicine test for patients with human Myeloma, a cancer found in bone marrow cells. "Ultimately we see this as a simple way to evaluate and treat Myeloma at a molecular level," said Dr. Brian Durie, IMF Chairman of the Board and Director of Myeloma Programs, Aptium Oncology. "This is one way to bring treatment for Myeloma into the 21st Century." "We are very excited about the important work pioneered by Chronix Biomedical. This is a company that can make a real difference in the testing and treatment of Myeloma as well as Mad Cow Disease," explained John Dilts, President of the Los Angeles and Westlake Village Chapters of Keiretsu Forum. -

State Strategies to Promote Angel Investment for Economic Growth*

Contact: Chris Hayter, Program Director, Economic Development Social, Economic, and Workforce Programs Division 202/624-7833 February 14, 2008 State Strategies to Promote Angel Investment for Economic Growth* Executive Summary Governors are increasingly interested in entrepreneurship because of its key role in driving business innovation. While entrepreneurs face several common challenges, including developing business acumen and making connections with experts and mentors, often their greatest challenge is raising capital. Entrepreneurs’ emerging technologies are frequently viewed as too risky for banks, private equity firms and venture capitalists, yet many fledgling companies require more investment to grow than can be raised from friends and family. Angel investors are increasingly stepping in to fill this gap. Angel investors are wealthy individuals with business or technology backgrounds who provide entrepreneurs with capital, connections, and guidance. They provide early-stage financing in a space once occupied by venture capitalists, who now invest primarily in larger deals and more mature companies. Individual angels invest between $5,000 and $100,000 in local and regional ventures, primarily in high-technology sectors, giving their investments local impact. In the past decade, many angel investors have formed and joined groups because investing through groups offers several advantages, most notably a large and more diverse portfolio, access to expertise, and higher deal flow. States increasingly recognize the value of angel investments and are adopting policies to promote them. Some have created statewide networks to assist the formation of angel groups, link angel groups to share best practices, and help groups invest together in companies that need more funding than a single group can offer. -

Annual Deal List

Annual Deal List 16th annual edition Contents Section Page Mergers & Acquisitions 04 1. Domestic 05 2. Inbound 15 3. Merger & Internal Restructuring 18 4. Outbound 19 Private Equity 23 QIP 67 IPO 69 Disclaimer This document captures the list of deals announced based on the information available in the public domain. Grant Thornton Bharat LLP does not take any responsibility for the information, any errors or any decision by the reader based on this information. This document should not be relied upon as a substitute for detailed advice and hence, we do not accept responsibility for any loss as a result of relying on the material contained herein. Further, our analysis of the deal values is based on publicly available information and appropriate assumptions (wherever necessary). Hence, if different assumptions were to be applied, the outcomes and results would be different. This document contains the deals announced and/or closed as of 23 December 2020. Please note that the criteria used to define Indian start-ups include a) the company should have been incorporated for five years or less than five years as at the end of that particular year and b) the company is working towards innovation, development, deployment and commercialisation of new products, processes or services driven by technology or intellectual property. Deals have been classified by sectors and by funding stages based on certain assumptions, wherever necessary. Dealtracker editorial team Pankaj Chopda and Monica Kothari Our methodology for the classification of deal type is as follows: Minority stake - 1%-25% | Strategic stake - 26%-50% | Controlling stake - 51%-75% | Majority stake - 76%-99% Maps are for graphical purposes only. -

LAEDC-IRG.Pdf

table of contents What is Innovation? 4 “Innovate LA!” 4 What’s in the Guide 5 Technical Assistance Providers 6 Advanced Transportation Technologies and Energy Centers 6 AERO Institute 6 Business Technology Center of Los Angeles County 7 California Applied Biotechnology Centers 8 California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences 8 California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology 9 California Manufacturing Technology Consulting 9 California NanoSystems Institute 10 California Space Authority 10 Cal NASBO 11 CALSTART 11 Caltech/MIT Enterprise Forum Industrial Relations Center 12 Center for Advanced Transportation Technologies 12 Centers for Applied Competitive Technologies 13 Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society 13 Center for International Trade Development 14 Center for Technology Commercialization 15 Center for Training, Technology and Incubation 15 Clearstone Venture Partners 16 College of the Canyons Advanced Technology Incubator 16 Digital Coast Roundtable 17 Entretech 17 Environmental, Health, Safety and Homeland Security Initiative 18 Fast Trac 19 Information Sciences Institute 19 Innovation Village 20 Keiretsu Forum Southern California 20 Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation 21 Los Angeles Regional Technology Alliance 21 Los Angeles Venture Association 22 Multimedia and Entertainment Initiative 23 NASA Commercialization Center - AccelTech 23 NASA Far West Regional Technology Transfer Center 23 National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 24 National Science -

Angel Investing: a Case Study of the Processes, Risk, And

ANGEL INVESTING: A CASE STUDY OF THE PROCESSES, RISK, AND INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN by Geoffroy T. Roach A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Business Administration UNIVERSITY OF PHOENIX December 2008 © 2008 by GEOFFROY T. ROACH ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ANGEL INVESTING: A CASE STUDY OF THE PROCESSES, RISK, AND INTERNAL RATE OF RETURN by Geoffroy T. Roach December 2008 Approved: Mark S. Allen, Ph.D., MBA, Mentor Alexander Hapka, Ph.D., Committee Member Eugene Lee, Ph.D., Committee Member Accepted and Signed: Mark S. Allen Nov 19, 2008 Accepted and Signed: Alexander Hapka Nov 19, 2008 Accepted and Signed: Eugene Lee Nov 19, 2008 __________________ Dawn Iwamoto, Ed.D. Date Dean, School of Advanced Studies University of Phoenix ABSTRACT One of the most difficult components in starting and growing a new enterprise is acquiring capital and other resources. Funding for many new enterprises comes from a large, yet relatively unidentified, group called angel investors. This case study is one of the few to examine the returns from angel investing and one of the first to examine the dynamics of angel investing groups. Computing internal rate of return for angel investments for Keiretsu Forum, an angel group, for the years 2000-2006 revealed that the investments generated higher returns than could have been obtained from the broader equity market as measured by popular index funds. Perhaps more important, this study also indicated that the processes developed by and regularly used by the angel group are effective at identifying potential failed deals and are not so restrictive as to bypass potential winners. -

Keiretsu Forum Due Diligence Handbook

“Great Association with Quality Deal Flow” Due Diligence Handbook Version 3.1 www.keiretsuforum.com Authors: Versions one and two (released in February of 2010 and November of 2010) were authored by Walt Spevak, Kent Mitchell, and Michael Gralnick, with the support, feedback, and participation of members of The Keiretsu Forum founding region’s Due Diligence Committee. Version three (released in November of 2013) was re-written and authored by Michael Gralnick. Version three reflects an expansion of the process that incorporates substantial modifications and additions based on evolutions in The Keiretsu Forum’s Due Diligence Processes since 2010. Version three also both adds new appendices that cover new procedures and modifies and expands upon several of the original appendices. Additional authors of new appendices are identified in each Appendix. Secondarily, version three begins the process of adding in supplemental appendices of reference materials for consideration. Handbook Copyright and Use: This Handbook is tailored to The Keiretsu Forum’s process, in which members conduct due diligence collaboratively, negotiate and arrange deal terms as a group, and in some cases syndicate investments among members in multiple chapters and regions around both the United States and the World, yet still make individual investment decisions and invest as individuals. The Handbook is provided to other Angel Investment Groups and individual Angel Investors under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike 3.0 license. You may modify or build upon the content of this work only if you do not use your revisions for commercial purposes (with the exception of seeking returns on investments after conducting your due diligence process), license any creations or works that derive from this Handbook under these same terms, and credit in writing within your works its authors. -

Department of Defense Emerging Technology Strategy: a Venture Capital Perspective

Department of Defense Emerging Technology Strategy: A Venture Capital Perspective Silicon Valley Defense Working Group April 2019 ABSTRACT The purpose of this paper is to assess the DOD’s efforts to access new sources of innovation through engagement with venture-backed emerging technology companies. The intended audience is threefold: DOD innovation policy makers, members of innovation units deployed to emerging tech ecosystems, and their overseers and financial backers in Congress. The paper starts by offering an overview of venture funding trends in areas of DOD interest both generally, and then in the Artificial Intelligence category. The encouraging conclusion is that at least on the surface, DOD efforts have been a stunning success. Based on publicly available data, venture funding to dual use companies the last five years has tripled from around $5B to nearly $15B. However, a deeper look as shown in the AI study reveals that the DOD overly focuses on the Early Stage. The corresponding geographic analysis of venture flows in 2018 compared to DOD innovation units shows an incomprehensible lack of engagement in Silicon Valley. The Valley sees nearly 55% of dual use funding but only 2.7% of DOD innovation budgets. The Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) based in Mountain View, California is the most important element of DOD’s emerging technology strategy. It’s resources should be sharply increased, and its mandate greatly expanded to reflect Silicon Valley’s importance as the leading emerging technology ecosystem. The second section lays out a multi-stage throughput model for dual use venture activity. The goal is to establish a common understanding by all three intended audiences of the VC market’s structure and inner workings. -

KYTO Technology and Life Science, Inc. (OTC

OTCQB: KBPH OCTOBER 1ST, 2018 MICROCAP CONFERENCE OCT. 1-2, 2018 NYC www.kytotech.com 1 OUR MISSON: CREATE FULLY LIQUID PUBLIC VEHICLE HOLDING a BROAD, DIVERSIFIED PORTFOLIO of VETTED ANGEL INVESTMENTS in LIFE SCIENCE and TECHNOLOGY LAUNCHING SERIES “B” $10 MILLION FUNDING EFFORT www.kytotech.com 2 KYTO’S VIEW OF THE START-UP WORLD • Start-up & Incubator Inundation, Large Cash Pools • 10’s of Thousands of Start-ups/year - Everywhere • Too many gadgets, niches, “popcorn stands” • Life Science Opportunity: More People, Older & Wealthier People • “Smarts” are global but ecosystems and funds are not!! • SILICON VALLEY STILL TOTALLY UNIQUE • “Tech Hot Areas” – Cybersecurity, AI, Blockchain, Cloud • “Life Science Hot Areas” – CRISPR, Medical Devices, Sensors, Healthcare Aps (e.g., new Apple watch) • KEY ISSUE: ACCESS TO BEST DEALS! www.kytotech.com 3 KYTO INVESTMENT APPROACH • No Management Fees, No Carry! VERY CAPITAL EFFICIENT! • ACCESS TO SUPERIOR DEALS! LEVERAGE MASSIVE DUE DILIGENCE. • Only invest in Sophisticated Angel Group Vetted and Funded Start-ups with Strong Fundamentals, Team and Winning Opportunities • ~50% Life Science, ~50% Technology Investments • Active Investor (continuous involvement) • USA & Canada Investment Focus to Start • KYTO Can Invest in One Follow-On Round with any Portfolio Company • Portfolio Expectations: 2-4 Years to Liquidity • In Case of Large Liquidity Event May Consider a Special Distribution to KYTO Shareholders www.kytotech.com 4 STEPS TO LIQUIDITY GOAL PHASE I PHASE II PHASE III PHASE IV SERIES “A” UNITS SERIES “B” OTC NASDAQ UNDERWAY or Common TRADING LISTING 10Q FILED Accredited Investors Large Accredited Investors PUBLIC ENTITY NOT LIQUID And Family Offices FULLY LIQUID! Q1, 2019 www.kytotech.com 5 CURRENT KYTO STATUS • SERIES “A” UNIT RAISE UNDERWAY - $1.5 MILLION ROUND • UNITS: $0.80/unit: 1 Preferred Share (2X liquid. -

Best Time for Angel Investors in India, Says Keiretsu Cap's Matthew Le Merle | Vccircle

4/1/2016 Best time for angel investors in India, says Keiretsu Cap's Matthew Le Merle | VCCircle ABOUT VCCEDGE TECHCIRCLE BIZCIRCLE EVENTS TRAINING AWARDS MOBILE APPS CAREERS Search Enter Keyword ... Welcome! Manu Toms | My Account | LOGOUT BUDGET 2016 DEALS CONSUMER FINANCE HEALTHCARE INFRASTRUCTURE MANUFACTURING TMT VCCTV HOME >> INTERVIEWS >> Advertisement Monday, March 28, 2016 17:30 IST Best time for angel investors in India, says Keiretsu Cap's Matthew Le Merle The coinvestment fund to help investors diversify portfolio. BY MANU P TOMS Keiretsu Capital, the coinvestment fund of global angel network Keiretsu Forum, raised around $6.5 million for its first angelinvestor fund in 2015. It is now planning to start a seed fund in India. During his recent visit to India, Matthew Le Merle, a managing partner at the fund, said it was contemplating an India focussed fund in 2017. The USbased crossborder network's Chennai chapter, its first in India, has invested a little over $1 million in earlystage startups, finishing its first year with around a dozen deals. Matthew Le Merle, a managing partner at In this interview with VCCircle, Le Merle, whose Keiretsu Capital firm, Fifth Era, advises countries and companies on growing the digital economy, outlines the investment goals for Keiretsu Capital's funds and the opportunities for angel investors in India. Edited excerpts: How do you see angel investing evolving in India? This is the best of times to become an angel investor in India. The Indian government has been clear that it expects a major proportion of future economic growth and expansion – and gains in jobs and wellbeing – to be driven by technology focused companies. -

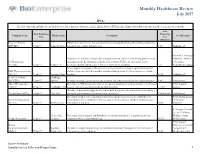

Monthly Healthcare Review July 2017

Monthly Healthcare Review July 2017 IPOs The following table includes the medical devices, biotechnology, pharmaceuticals, and healthcare IPO pricings, filings and withdrawals announced over the previous month. Last Last Financing Financing Company Name HQ Location Description Lead Manager Date Size (Millions) Promore Pharma Owner and operator of a bio-pharmaceutical company developing therapeutic peptides for (PROMO) 6-Jul-17 Solna, Sweden treating local wounds and infections. 8.74 Undisclosed Network 1 Financial Operator of a molecular diagnostics company offering a DNA-based testing platform that Securities, Network Co-Diagnostics specializes in the development of probes for real-time PCR to its customers. It also 1 Securities, (CODX) 12-Jul-17 Sandy, UT develops a design and analytics software for DNA test designing. 7.07 WallachBeth Capital The company is engaged in the extraction and purification of heparin glycosaminoglycan NKF Pharmaceuticals and develops a controlled, traceable, and detectable process for the production of crude (603707) 13-Jul-17 Nanjing, China heparin. 67.22 Undisclosed NextCell Pharma Huddinge, (NEXTCL) 13-Jul-17 Sweden Provider of medical products for autoimmune and inflammatory diseases and transplants. 2.88 Undisclosed Akcea Therapeutics Developer of RNA-targeted antisense therapeutic products created to transform the lives of BMO Capital (AKCA) 14-Jul-17 Cambridge, MA patients with serious cardiometabolic lipid disorders. 175.00 Markets Provider of nutritional supplements and medical devices for the restoration of the ability to PharmaNutra (PHN) 18-Jul-17 Pisa, Italy articulate and movement in osteoarticular affections. Undisclosed Undisclosed Developer of innovative nanoparticle-based treatments created to treat ocular diseases BofA Merrill Lynch, Kala Pharmaceuticals affecting both front and back of the eye, such as dry eye disease and post-surgical ocular J.P Morgan (KALA) 20-Jul-17 Waltham, MA inflammation and pain. -

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding Sources for Entrepreneurs and Small Business

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding sources for entrepreneurs and small business Sixth Edition Introduction Denver Economic Development & Opportunity (DEDO) Definitions is pleased to release this sixth edition of the Denver Venture Capital – Venture capital is capital provided by investors to Capital Matrix. small businesses and start-up firms that demonstrate possible high- growth opportunities. Venture capital investments have a potential for This publication is designed as a tool to assist business considerable loss or profit and are generally designated for new and owners and entrepreneurs with discovering the myriad speculative enterprises that seek to generate a return through a of capital sources in and around the Mile High City. potential initial public offering or sale of the company. The Denver Capital Matrix provides a comprehensive Angel Investor – An angel investor is a high net worth individual active in directory of financing sources, from traditional bank venture financing, typically participating at an early stage of growth. lending, to venture capital firms, private equity firms, angel Private Equity – Private equity is an individual or consortium of investors investors, mezzanine sources and more. and funds that make investments directly into private companies or Small businesses provide the greatest opportunity for job initiate buyouts of public companies. Private equity is ownership in private companies that is not listed or traded on public exchanges. This is creation today. Yet, a lack of needed financing often prevents considered an illiquid and long-term investment. businesses from implementing expansion plans and adding payroll. Through this updated resource, DEDO strives to help Mezzanine Financing – Mezzanine financing is a hybrid of debt and connect businesses to equity financing that is typically used to finance the expansion of start- up and expansion capital so that they can thrive in existing companies.