Department of Defense Emerging Technology Strategy: a Venture Capital Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Private Equity Firms Fueling the Growth of Electronic Trading June

Private Equity Firms Fueling the Growth of Electronic Trading June 23, 2007 Article Excepts: Steve McLaughlin, managing partner in Financial Technology Partners, the only investment banking firm focused exclusively on financial technology deals, insists the trend is going to continue because there's always innovation in the space, but maybe not at the current pace. "It's going to slow because so much attention has been brought to this space recently," he says. "A lot of the better later-stage companies [already] have done their transactions." McLaughlin — who gave Liquidnet its eye-popping $1.8 billion valuation in 2005, which resulted in a $250 million investment from TCV and Summit Equity Investors — points to Liquidnet as an example. "Liquidnet is a very simple idea — the business plan and the idea you could write on the back of a postage stamp," he contends. "It was very elegant in the way that [the company] put it together and marketed itself as the Napster of electronic trading. ... Financial technology is more about using existing technologies to solve complex problems." FT Partner's McLaughlin, however, says, "There are still plenty of deals out there. A lot of the companies getting finance were created five or six years ago. There are plenty of firms being created now that in five or six years will be looking for capital. But a lot of the really good companies have been pursued by these private equity firms" Full Article: It's good to be in the financial technology industry these days — especially if your company is getting calls from private equity firms looking to invest in one of the economy's hottest growth sectors. -

Avetta and BROWZ Combine to Form One of the World's Leading

Avetta and BROWZ Combine to Form One of the World’s Leading Providers of Supply Chain Risk Management Transaction expands global network to 85,000 customers in over 100 countries with a configurable SaaS platform and industry leading customer service Feb. 14, 2019—OREM, Utah—Avetta and BROWZ, two leading providers of SaaS based supply chain risk management software, today announced they have combined to form a new, market leading organization focused on delivering the best in supply chain risk management services to companies world-wide. The transaction further solidifies Avetta’s position as a world-class organization, innovator and thought leader, expanding the company’s global network to 85,000 customers in over 100 countries in the fast growing $14 billion global marketplace for supply chain risk management solutions. Avetta and BROWZ combine more than three decades of experience in making industries safer, more sustainable and compliant by vetting and qualifying the suppliers that support their global clients. Avetta and BROWZ’s 450 combined clients include blue chip companies in industry verticals such as energy, chemicals, manufacturing, utilities, construction materials, facilities management, communications, transportation, logistics & retail, mining, aerospace & defense and food & beverage. These industry leaders require better visibility into supply chain risks, such as workplace health & safety, sustainability, modern slavery, data privacy, anti-bribery & corruption, regulatory and insurance compliance. Together, the companies’ market-leading technology platform and products strengthen sustainable connections between clients and suppliers, while streamlining and simplifying the engagement process for both parties. Avetta and BROWZ share a common vision of putting customers first and a belief that the solutions offered to their clients should be configurable to address the specific needs and requirements of their client base across industries and geographies. -

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding Sources for Entrepreneurs and Small Business

DENVER CAPITAL MATRIX Funding sources for entrepreneurs and small business. Introduction The Denver Office of Economic Development is pleased to release this fifth annual edition of the Denver Capital Matrix. This publication is designed as a tool to assist business owners and entrepreneurs with discovering the myriad of capital sources in and around the Mile High City. As a strategic initiative of the Denver Office of Economic Development’s JumpStart strategic plan, the Denver Capital Matrix provides a comprehensive directory of financing Definitions sources, from traditional bank lending, to venture capital firms, private Venture Capital – Venture capital is capital provided by investors to small businesses and start-up firms that demonstrate possible high- equity firms, angel investors, mezzanine sources and more. growth opportunities. Venture capital investments have a potential for considerable loss or profit and are generally designated for new and Small businesses provide the greatest opportunity for job creation speculative enterprises that seek to generate a return through a potential today. Yet, a lack of needed financing often prevents businesses from initial public offering or sale of the company. implementing expansion plans and adding payroll. Through this updated resource, we’re striving to help connect businesses to start-up Angel Investor – An angel investor is a high net worth individual active in and expansion capital so that they can thrive in Denver. venture financing, typically participating at an early stage of growth. Private Equity – Private equity is an individual or consortium of investors and funds that make investments directly into private companies or initiate buyouts of public companies. Private equity is ownership in private companies that is not listed or traded on public exchanges. -

Want to Crush Competitors? Forget Softbank, Blackstone Suggests; It Can Write $500 Million Checks, Too

September 20, 2019 Extra Crunch Want to crush competitors? Forget SoftBank, Blackstone suggests; it can write $500 million checks, too Connie Loizos @cookie JK: There are 2,600 altogether across 24 offices. an investing giant is the better gig? ack in January, Blackstone — the TC: Is your group investing a discreet pool of JK: If you’re an intellectually curious individ- investment firm whose assets un- capital? ual, there are so many signals [coming through der management surpassed a jaw- Blackstone] that it’s almost a proxy for the dropping half a trillion dollars earlier JK: At some point, we’ll have a dedicated pool world. It’s like manna from heaven. It’s not like Bthis year — quietly began piecing together a of capital, but as a firm, we’ve been investing in they’re doing a single-threaded approach. The new, growth equity platform called Blackstone growth equity for some time [so have relied on nature of the challenges across our companies Growth, or BXG. Step one was hiring away Jon other funds within Blackstone to date]. is so vast and so varying that whether you’re Korngold from General Atlantic, where looking at a fast-growing retailer or a cell phone he’d spent the previous 18 years, including TC: There’s no shortage of growth equity tower in another country, the nature of the tasks as a managing director and a member of its in the world right now. What is Blackstone is always changing. management committee. building that’s so different? Step two has been for Korngold, who is re- TC: SoftBank seems to have shaken things sponsible for running the new program, to build JK: The sheer scale of the operation is different. -

Chronix Biomedical Secures $1.6 Million in Financing

Chronix Biomedical Secures $1.6 Million in Financing Led by Nation's Largest Angel Investor Network -- Keiretsu Forum LOS ANGELES, CA -- (MARKET WIRE) -- 05/24/2005 -- Keiretsu Forum, the nation's largest angel investor network, today announced its investment in Chronix Biomedical, an applied genomics company based in San Jose with research facilities in Göttingen, Germany. Chronix Biomedical has closed this round as a convertible note of $1.6 Million with Keiretsu Forum members investing $1.1 Million. The company develops products and services for the detection and monitoring of chronic diseases with particular focus on genomic-based assays that will be utilized in the emerging fields of "theranostics" and "pharmacogenetics." Chronix's first and second commercial products, the Göttingen Living Test (GLT) is a test for the detection of cows at risk for developing bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE) or mad cow disease and the humans' form of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (vCJD). Its third commercial product is a personalized medicine test for patients with human Myeloma, a cancer found in bone marrow cells. "Ultimately we see this as a simple way to evaluate and treat Myeloma at a molecular level," said Dr. Brian Durie, IMF Chairman of the Board and Director of Myeloma Programs, Aptium Oncology. "This is one way to bring treatment for Myeloma into the 21st Century." "We are very excited about the important work pioneered by Chronix Biomedical. This is a company that can make a real difference in the testing and treatment of Myeloma as well as Mad Cow Disease," explained John Dilts, President of the Los Angeles and Westlake Village Chapters of Keiretsu Forum. -

The Definitive Review of the US Venture Capital Ecosystem Credits & Contact

Q4 2019 In partnership with Angel & seed deal value remains Value of VC deals with 2019 marks record year for elevated in 2019 at $9.1B nontraditional investor VC exit value despite tepid exit Page 7 participation approaches $100B for activity in Q4 second consecutive year Page 32 Page 27 The definitive review of the US venture capital ecosystem Credits & contact PitchBook Data, Inc. JOHN GABBERT Founder, CEO ADLEY BOWDEN Vice President, Research & Analysis Content NIZAR TARHUNI Director, Research JAMES GELFER Senior Strategist & Lead Analyst, VC ALEX FREDERICK Senior Analyst, VC CAMERON STANFILL, CFA Analyst II, VC KYLE STANFORD Analyst, VC VAN LE Senior Data Analyst RESEARCH Contents [email protected] Report & cover design by CONOR HAMILL Executive summary 3 National Venture Capital Association (NVCA) BOBBY FRANKLIN President & CEO NVCA policy highlights 4 MARYAM HAQUE Senior Vice President of Industry Advancement Overview 5-6 CASSIE HODGES Director of Communications DEVIN MILLER Manager of Communications & Digital Angel, seed & first financings 7-8 Strategy Early-stage VC 9-10 Contact NVCA nvca.org Late-stage VC 11-12 [email protected] SVB: Resilience is the theme for 2020 14-15 Silicon Valley Bank Deals by region 17 GREG BECKER Chief Executive Officer MICHAEL DESCHENEAUX President Deals by sector 18-21 BEN STASIUK Vice President SVB: Global trade tensions create stress—and opportunity 22-23 Contact Silicon Valley Bank svb.com Female founders 24-25 [email protected] Nontraditional investors 27-28 Carta: How dual-class and single-class companies Carta 29-30 MISCHA VAUGHN Head of Editorial compare JEFF PERRY Vice President of Revenue D’ARCY DOYLE Senior Vice President of Investor Exits 32-33 Services Sales VINCENT TIMONEY Director of Channel Strategy Fundraising 34-35 Contact Carta Methodology 37 carta.com 2 Q4 2019 PITCHBOOK-NVCA VENTURE MONITOR Executive summary The big question mark at the start of 2019 was how VC deal value would fare after a historic showing in the year prior. -

State Strategies to Promote Angel Investment for Economic Growth*

Contact: Chris Hayter, Program Director, Economic Development Social, Economic, and Workforce Programs Division 202/624-7833 February 14, 2008 State Strategies to Promote Angel Investment for Economic Growth* Executive Summary Governors are increasingly interested in entrepreneurship because of its key role in driving business innovation. While entrepreneurs face several common challenges, including developing business acumen and making connections with experts and mentors, often their greatest challenge is raising capital. Entrepreneurs’ emerging technologies are frequently viewed as too risky for banks, private equity firms and venture capitalists, yet many fledgling companies require more investment to grow than can be raised from friends and family. Angel investors are increasingly stepping in to fill this gap. Angel investors are wealthy individuals with business or technology backgrounds who provide entrepreneurs with capital, connections, and guidance. They provide early-stage financing in a space once occupied by venture capitalists, who now invest primarily in larger deals and more mature companies. Individual angels invest between $5,000 and $100,000 in local and regional ventures, primarily in high-technology sectors, giving their investments local impact. In the past decade, many angel investors have formed and joined groups because investing through groups offers several advantages, most notably a large and more diverse portfolio, access to expertise, and higher deal flow. States increasingly recognize the value of angel investments and are adopting policies to promote them. Some have created statewide networks to assist the formation of angel groups, link angel groups to share best practices, and help groups invest together in companies that need more funding than a single group can offer. -

Annual Deal List

Annual Deal List 16th annual edition Contents Section Page Mergers & Acquisitions 04 1. Domestic 05 2. Inbound 15 3. Merger & Internal Restructuring 18 4. Outbound 19 Private Equity 23 QIP 67 IPO 69 Disclaimer This document captures the list of deals announced based on the information available in the public domain. Grant Thornton Bharat LLP does not take any responsibility for the information, any errors or any decision by the reader based on this information. This document should not be relied upon as a substitute for detailed advice and hence, we do not accept responsibility for any loss as a result of relying on the material contained herein. Further, our analysis of the deal values is based on publicly available information and appropriate assumptions (wherever necessary). Hence, if different assumptions were to be applied, the outcomes and results would be different. This document contains the deals announced and/or closed as of 23 December 2020. Please note that the criteria used to define Indian start-ups include a) the company should have been incorporated for five years or less than five years as at the end of that particular year and b) the company is working towards innovation, development, deployment and commercialisation of new products, processes or services driven by technology or intellectual property. Deals have been classified by sectors and by funding stages based on certain assumptions, wherever necessary. Dealtracker editorial team Pankaj Chopda and Monica Kothari Our methodology for the classification of deal type is as follows: Minority stake - 1%-25% | Strategic stake - 26%-50% | Controlling stake - 51%-75% | Majority stake - 76%-99% Maps are for graphical purposes only. -

LAEDC-IRG.Pdf

table of contents What is Innovation? 4 “Innovate LA!” 4 What’s in the Guide 5 Technical Assistance Providers 6 Advanced Transportation Technologies and Energy Centers 6 AERO Institute 6 Business Technology Center of Los Angeles County 7 California Applied Biotechnology Centers 8 California Institute for Quantitative Biosciences 8 California Institute for Telecommunications and Information Technology 9 California Manufacturing Technology Consulting 9 California NanoSystems Institute 10 California Space Authority 10 Cal NASBO 11 CALSTART 11 Caltech/MIT Enterprise Forum Industrial Relations Center 12 Center for Advanced Transportation Technologies 12 Centers for Applied Competitive Technologies 13 Center for Information Technology Research in the Interest of Society 13 Center for International Trade Development 14 Center for Technology Commercialization 15 Center for Training, Technology and Incubation 15 Clearstone Venture Partners 16 College of the Canyons Advanced Technology Incubator 16 Digital Coast Roundtable 17 Entretech 17 Environmental, Health, Safety and Homeland Security Initiative 18 Fast Trac 19 Information Sciences Institute 19 Innovation Village 20 Keiretsu Forum Southern California 20 Los Angeles County Economic Development Corporation 21 Los Angeles Regional Technology Alliance 21 Los Angeles Venture Association 22 Multimedia and Entertainment Initiative 23 NASA Commercialization Center - AccelTech 23 NASA Far West Regional Technology Transfer Center 23 National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) 24 National Science -

Santa Barbara County Employees' Retirement System

Santa Barbara County Employees’ Retirement System 2021 Private Equity Strategic Plan Agenda • Program Review 3 • Portfolio Snapshot and Performance Summary 9 • Strategic Plan 13 • Appendix 20 Program Review PE Portfolio Highlights - September 30, 2020 Hamilton Lane (“HL”) is entering our 15th year of building the Santa Barbara County Employees’ Retirement System (“SBCERS”) PE Program Performance • Since inception IRR of 12.67% outperforms the benchmark (Russell 3000 + 300 bps) by 28 bps • Double-digit performance for the one-year period, with a point-to-point IRR of 14.96% Strategic Objectives • Fulfilled all objectives outlined in the 2020 Strategic Plan • PE target of 10% established in 2016; Portfolio at 11.45% as of September 30, 2020 • Established a strong foundation of top tier managers Additional Highlights • Accessed highly sought, oversubscribed funds • Received preferred legal terms for one fund in 2020 as a result of the HL platform • Presented Private Equity 101 to new Board Members Hamilton Lane | Global Leader in the Private Markets Proprietary and Confidential | 4 SBCERS’ Private Equity Investment Milestones Hamilton Lane was hired by SBCERS in 2006 to select new investments, monitor, and provide advice for the private equity portfolio 2005 - Lexington Capital Partners VI • First private equity investment (made by SBCERS) 2006 - HL hired to build long-term PE allocation to 5% • Original contract allowed HL to invest $80M on behalf of SBCERS 2008 - Amendment to contract giving HL full discretion • Recommended annual commitment -

Developing an Angel Investor Forum to Complement an Engineering School's Entrepreneurship Initiatives

AC 2007-824: DEVELOPING AN ANGEL INVESTOR FORUM TO COMPLEMENT AN ENGINEERING SCHOOL'S ENTREPRENEURSHIP INITIATIVES Thomas Duening, Arizona State University Page 12.484.1 Page © American Society for Engineering Education, 2007 Developing an Angel Investor Forum to Complement an Engineering School’s Entrepreneurship Initiatives Page 12.484.2 Page Background After two years of decline, entrepreneurial activity in the United States increased from 10.5 percent in 2002 to 11.9 percent in 2003. This level of activity ranks the U.S. 7 th among 31 nations surveyed by the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor in Total Entrepreneurial Activity (TEA). 1 Importantly, the U.S. is the only nation among the G7 to register a TEA score in the top ten. Today, nearly 50 percent of the growth in the U.S. economy can be attributed to entrepreneurial activity; much of this activity is in the technology sector. Since success in a technology venture requires both technical feasibility and economic viability an engineering curriculum that integrates both aspects is of considerable value. 2 Of the over 200 thousand graduates of college engineering and science programs each year in the U.S., a growing proportion seek employment in entrepreneurial ventures or are starting their own ventures. This trend among engineering and science graduates requires “a new type of engineer, an entrepreneurial engineer, who needs a broad range of skills and knowledge above and beyond a strong science and engineering background.” 3 Companies around the world are actively seeking innovators who can solve business problems and assess risks, in addition to being technically proficient. -

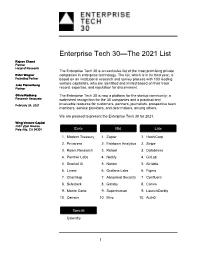

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List

Enterprise Tech 30—The 2021 List Rajeev Chand Partner Head of Research The Enterprise Tech 30 is an exclusive list of the most promising private Peter Wagner companies in enterprise technology. The list, which is in its third year, is Founding Partner based on an institutional research and survey process with 103 leading venture capitalists, who are identified and invited based on their track Jake Flomenberg Partner record, expertise, and reputation for discernment. Olivia Rodberg The Enterprise Tech 30 is now a platform for the startup community: a Research Associate watershed recognition for the 30 companies and a practical and February 24, 2021 invaluable resource for customers, partners, journalists, prospective team members, service providers, and deal makers, among others. We are pleased to present the Enterprise Tech 30 for 2021. Wing Venture Capital 480 Lytton Avenue Palo Alto, CA 94301 Early Mid Late 1. Modern Treasury 1. Zapier 1. HashiCorp 2. Privacera 2. Fishtown Analytics 2. Stripe 3. Roam Research 3. Retool 3. Databricks 4. Panther Labs 4. Netlify 4. GitLab 5. Snorkel AI 5. Notion 5. Airtable 6. Linear 6. Grafana Labs 6. Figma 7. ChartHop 7. Abnormal Security 7. Confluent 8. Substack 8. Gatsby 8. Canva 9. Monte Carlo 9. Superhuman 9. LaunchDarkly 10. Census 10. Miro 10. Auth0 Special Calendly 1 2021 The Curious Case of Calendly This year’s Enterprise Tech 30 has 31 companies rather than 30 due to the “curious case” of Calendly. Calendly, a meeting scheduling company, was categorized as Early-Stage when the ET30 voting process started on January 11 as the company had raised $550,000.