In Re Marriage of Burkle RB

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Yucaipa Companies

YUCAIPA COMPANIES: “POSTER CHILD FOR THE ILLS OF POLITICAL DONATIONS AND BUSINESS” Yucaipa is a holding company that invests across a wide range of industries—from groceries to logistics to magazine distribution. Ronald Burkle, chairman of Yucaipa, has been a multi-million fundraiser and donor for Bill and Hillary Clinton and in Bill Clinton’s post-presidency, Burkle has emerged as a close friend and rain- maker for the Clintons – and the friendship has been prosperous for both. “The mainstream business press beats up on [Burkle], essentially for buying access and influence among politicians and leaders of the pension funds that invest with him (FORBES included). ‘I basically became the poster child for the ills of political donations and business. It’s preposterous!’ Burkle protests.” [Forbes, 12/11/06] BILL CLINTON AND YUCAIPA 2006: Bill Clinton Has Guaranteed Payments “Over $1,000” From Yucaipa And Has Invested In Several Yucaipa Funds. Hillary’s financial disclosure report indicates that Bill Clinton has “over $1,000” in guaranteed payments from Yucaipa Global Holdings. Because the Clintons are not required to report the actual amount or any range of income that is more specific than “over $1,000” we do not know how much Bill has been compen- sated. Through WJC International Investments GP, Bill Clinton invests in Yucaipa Global Holdings and Yu- caipa Global Partnership. The Yucaipa Global Partnership Fund “invests in securities of corporations that con- duct significant operations in foreign countries.” Clinton reported interest income between $201-$1,000 from Yucaipa Global Holdings and between $1,001-$2,500 from Yucaipa Global Partnership Fund. -

The Defined-Contribution Retirement Plan,” Barry Bennett Argues That DC Plans Are Not Really Pensions at All

Corporate Retirement Security Other Blackwell titles on Business and Society The Ethics of Executive Compensation, edited by Robert W. Kolb (2006) Corporate Retirement Security: Social and Ethical Issues, edited by Robert W. Kolb (2007) The Ethics of Genetic Commerce, edited by Robert W. Kolb (2007) Corporate Retirement Security Social and Ethical Issues Edited by Robert W. Kolb © 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd BLACKWELL PUBLISHING 350 Main Street, Malden, MA 02148-5020, USA 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford OX4 2DQ, UK 550 Swanston Street, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia The right of Robert W. Kolb to be identified as the Author of the Editorial Material in this Work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs, and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. First published 2007 by Blackwell Publishing Ltd 1 2007 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Corporate retirement security: social and ethical issues / edited by Robert W. Kolb. p. cm. — (The Leeds School series on business and society) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-1-4051-5048-4 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. Pension trusts—United States. 2. Social responsibility of business—United Stages. I. Kolb, Robert W., 1949– HD7105.45.U6C67 2007 331.25’.20973—dc22 2007000201 A catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library. Set in 10/12.5, Minion by Charon Tec Ltd (A Macmillan Company), Chennai, India www.charontec.com Printed and bound in XX by XX The publisher’s policy is to use permanent paper from mills that operate a sustainable forestry policy, and which has been manufactured from pulp processed using acid- free and elementary chlorine-free practices. -

LISTING MEMORANDUM £7500000 Soho House

LISTING MEMORANDUM £7,500,000 Soho House Bond Limited 9⅛% Senior Secured Notes due 2018 Our Company Guarantees . The notes are fully and unconditionally guaranteed, jointly and severally, by Soho House & Co Limited and certain of our existing We are a fully integrated hospitality company that operates and future subsidiaries. exclusive, private members clubs as well as hotels, restaurants and spas across major metropolitan cities including London, New York, Los Angeles, Miami, Ranking . The notes and the guarantees rank equal in right of Toronto and Berlin. We were founded in London in 1995 with a vision to payment with all of the issuer’s and the guarantors’ existing and future senior create an exclusive social gathering place for like-minded people in the film, indebtedness (subject to the waterfall provisions in the Intercreditor Agreement media and creative industries to network, entertain and/or host private functions in respect of proceeds from the enforcement of collateral), rank senior in right such as meetings, special events and film screenings. As of September 27, of payment to all of the issuer’s and the guarantors’ existing and future 2015, we had over 52,000 members with a global waiting list of over 32,000 subordinated indebtedness and be effectively senior to all of the issuer’s and the potential members and we operated 15 Houses, 30 restaurants, 12 spas and 481 guarantors’ existing and future unsecured indebtedness to the extent of the value hotel rooms across the portfolio. of the collateral securing the notes and the guarantees. The Notes Security Interest . The notes and the guarantees are secured by security interests as more specifically described under “Description of Notes— Offering . -

Takeover Law and Practice Guide 2020

Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz Takeover Law and Practice 2020 This outline describes certain aspects of the current legal and economic environment relating to takeovers, including mergers and acquisitions and tender offers. The outline topics include a discussion of directors’ fiduciary duties in managing a company’s affairs and considering major transactions, key aspects of the deal-making process, mechanisms for protecting a preferred transaction and increasing deal certainty, advance takeover preparedness and responding to hostile offers, structural alternatives and cross-border transactions. Particular focus is placed on recent case law and developments in takeovers. This edition reflects developments through September 2020. © October 2020 Wachtell, Lipton, Rosen & Katz All rights reserved. Takeover Law and Practice TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. Current Developments ..............................................................................1 A. Overview ............................................................................. 1 B. M&A Trends and Developments ........................................ 2 1. Deal Activity ........................................................... 2 2. Unsolicited M&A.................................................... 4 3. Private Equity Trends ............................................. 5 4. SPAC Trends .......................................................... 6 5. Acquisition Financing ............................................. 8 6. Shareholder Litigation ........................................... -

Obama, Gay, Blackmail -- Rezko, Fitzgerald, Blagojevich

Obama, gay, blackmail -- Rezko, Fitzgerald, Blagojevich NewsFollowUp.com Obama CIA pictorial index search sitemap home .... OBAMA TOP 10 FRAUD .... Influence, Power News for the 99% Obama Groomed for 30 years by Ford Foundation ...................................Refresh F5...archive and Trilateral Commission and CIA to become home President 50th Anniversary of JFK assassination "Event of a Lifetime" at the Fess Parker Double Tree Inn. JFKSantaBarbara. NFU MOST ACTIVE PA Go to Alphabetic list Obama Gay, Chicago Academic Freedom Conference Bush Neocon Pedophile Index Obama Death List Rothschild Timeline Rothschild Research Sources Bush / Clinton Body Count Reagan, Clinton, Bush Crime Families DeLauro / Turtin, Obama body count Ban ki Moon, Sun Myung Moon = go to other NFU pages http://www.newsfollowup.com/influence_gen.htm[5/28/2014 3:07:19 PM] Obama, gay, blackmail -- Rezko, Fitzgerald, Blagojevich WayneMadsen Report has been told that Emanuel was aware of the damaging nature of the "thousands" of FBI intercepted phone calls to him and Obama and wanted to divert Fitzgerald and the FBI away from he and the president-elect to Blagojevich and Harris. Fitzgerald, known as the man who covered up key elements of the 1993 World Trade Center bombing and saw to it that the legal ground was laid for a commutation of the prison sentence of Dick Cheney’s chief of staff Scooter Libby in the Bush administration’s cover-up of the outing by the media of CIA non-official cover agent Valerie Plame Wilson, decided to seek authorization for the early morning arrest of Blagojevich to protect Obama and Emanuel, as well as Bush. -

Case 2:11-Cv-05196-WJM-MF Document 25 Filed 03/16/12 Page 1 of 60 Pageid: 271

Case 2:11-cv-05196-WJM-MF Document 25 Filed 03/16/12 Page 1 of 60 PageID: 271 COHN LIFLAND PEARLMAN HERRMANN & KNOPF LLP PETER S. PEARLMAN Park 80 West-Plaza One 250 Pehle Ave., Suite 401 Saddle Brook, NJ 07663 Telephone: 201/845-9600 201/845-9423 (fax) Liaison Counsel ROBBINS GELLER RUDMAN & DOWD LLP SAMUEL H. RUDMAN ERIN W. BOARDMAN 58 South Service Road, Suite 200 Melville, NY 11747 Telephone: 631/367-7100 631/367-1173 (fax) Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs [Additional counsel appear on signature page.] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY RICKY DUDLEY, Individually and On Behalf ) No. 2:11-cv-05196-WJM-MF of All Others Similarly Situated, ) CLASS ACTION Plaintiff, AMENDED COMPLAINT FOR vs. VIOLATION OF THE FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS CHRISTIAN W. E. HAUB, ERIC CLAUS, BRENDA M. GALGANO, RONALD MARSHALL, SAMUEL MARTIN, THE YUCAIPA COMPANIES LLC, RONALD BURKLE AND FREDERIC BRACE, ) ) Defendants. ) ) Case 2:11-cv-05196-WJM-MF Document 25 Filed 03/16/12 Page 2 of 60 PageID: 272 Lead Plaintiffs City of New Haven Employees’ Retirement System and Plumbers and Pipefitters Locals 502 & 633 Pension Trust Fund (“Lead Plaintiffs” or “Plaintiffs”) have alleged the following based upon the investigation of Plaintiffs’ counsel, which included a review of United States Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings by The Great Atlantic & Pacific Tea Company, Inc. (“A&P” or the “Company”), as well as regulatory filings and reports, securities analysts’ reports and advisories about the Company, press releases and other public statements issued by the Company, media reports about the Company, interviews with former employees of the Company, and public filings in A&P’s Chapter 11 proceedings in the U.S. -

Jewish Influence: an Introduction

NOTE: "The list below is available on the internet. A random sampling of the names were found to be generally accurate. Since the source is the internet, the reader is advised to also authenticate. The link is: http://www.subvertednation.net/jew-lists/ The below link from the Jewish Virtual Library contains many of the names identified on pages 36 – 38. http://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/US- Israel/obamajews.html Jewish Influence: An Introduction We have been accused of having “Jew on the brain”; of being negatively obsessed with the Jews, and of being “anti-Semitic.” Yet Jewish influence over the affairs of the world are undeniably powerful, far out of proportion to their numbers. Their role in shaping public opinion through their media interests, and their mastering of the world of business and trade is pivotal to the world economy. As a group they are the most successful in terms of income and wealth and they have reached the highest echelons or the pinnacle of power in every field. Jews are the masters of Hollywood, they are the masters of all forms of media, radio, and television. They are masters of trade and commerce and banking, medicine, and law. The following lists we believe prove this reality. Jewish Lists The lists below are available on the internet. A spot check of several of the names found it to be generally accurate, though we cannot vouch for ALL of the names, and some titles may be out of date. The second list claims to be updated in 2012. They are followed by quotes on Jewish control. -

2017 Annual Report Contents 2 a Road Map to Our Future 6 Convening Conversations

Smithsonian / 2017 Annual Report Contents 2 A Road Map to Our Future 6 Convening Conversations 18 Engaging Audiences 24 Campaign Sets Record 26 Recognition and Reports Left: Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors offered visitors a unique sensory experience— a chance to step into six kaleidoscopic rooms that created the illusion of infinite space. An Instagram favorite, the exhibition helped the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden attract more than 10,000 new members in 2017 alone. Front Cover: In artist Yayoi Kusama’s The Obliteration Room, the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden invited visitors to obliterate an entirely white space with multicolored polka-dot stickers. The installation is part of the museum’s blockbuster exhibition Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, which is touring five North American cities through 2019. A ROAD MAP TO OUR FUTURE A ROAD MAP TO he year 2017 was successful for the Smithsonian by any measure. Our curators opened insightful and inspirational exhibitions. Our scientists continued to do T groundbreaking research that benefits humankind. Our educators are reaching more people than ever before with compelling programming. The years-long, Smithsonian-wide campaign soared past its goal, setting up success for decades to come. This annual report is a terrific opportunity to look back and recognize all of these impressive achievements and many more brought to life by the Smithsonian’s dedicated and talented staff and volunteers. But while it is important to reflect on the past year, we must also redirect our eyes from the rearview mirror to the road that lies before us. This is especially true now, since 2017 saw the unveiling of our bold new strategic plan that will guide us through the year 2022. -

Pension Fund Politics

Pension Fund Politics Pension Fund Politics The Dangers of Socially Responsible Investing Edited by Jon Entine The AEI Press Publisher for the American Enterprise Institute WASHINGTON, D.C. Contents 1. THE POLITICIZATION OF PUBLIC INVESTMENTS, Jon Entine 1 The Problematic History of Social Investing of Public Pension Funds 3 The Essays 9 Notes 11 2. SOCIAL INVESTING: PENSION PLANS SHOULD JUST SAY “NO,” Alicia H. Munnell and Annika Sundén 13 What Is Social Investing and How Much Is Going On? 14 Prevalence of Various Approaches to Social Investing 19 How Does Social Investing Affect Companies? 20 The Textbook Argument 21 Counterexamples 23 South African Boycott 25 How Does Social Investing Affect Shareholder Returns? 28 Theory 29 Evidence 30 Should Pension Plans Engage in Social Investing? 34 Public Pensions 35 Private Pensions 42 Conclusion 45 Notes 48 v vi PENSION FUND POLITICS 3. WHY SOCIAL INVESTING THREATENS PUBLIC PENSION FUNDS, CHARITABLE TRUSTS, AND THE SOCIAL SECURITY TRUST FUND, Charles E. Rounds Jr. 56 Introduction 56 Trustees and Social Investment 61 State Pension Funds 63 Charitable Funds 67 Social Security 71 Conclusion 76 Notes 77 4. THE STRATEGIC USE OF SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE INVESTING, Jarol B. Manheim 81 Balancing the Corporate Books 82 Power Structure Analysis: A Pathology of Stakeholder Relationships 83 Anticorporate Activists and Public Pension Funds 86 Proxy Wars and “Social Netwars” 94 Conclusion 97 Notes 99 ABOUT THE AUTHORS 103 INDEX 107 1 The Politicization of Public Investments Jon Entine Should public pension funds invest the assets of their retirees based on the political views of the politicians who manage them? Should personal morality and ideology, which vary dramatically across the country, influence public investments, including Social Security? Traditionally, public investments have been managed according to strict fiduciary principles designed to protect American work- ers and taxpayers. -

Reichtum Update

Reichtum/Update 2008 Axel Köhler-Schnura © Anschrift: Spendenkonten: ethecon EthikBank Freiberg Stiftung Ethik & Ökonomie Konto 30 45 536 Wilhelmshavener Straße 60 BLZ 830 944 95 10551 Berlin IBAN DE 58 830 944 95 000 30 45 536 Fon/Fax 030 - 22 32 51 45 BIC GENODEF1ETK eMail [email protected] GLS-Bank Bochum verantwortlicher Vorstand: Konto 6002 562 100 Dipl. Kfm. BLZ 430 609 67 Axel Köhler-Schnura (Gründungsstifter) IBAN DE05 430 609 67 6002 562 100 Postfach 15 04 35 BIC GENODEM1GLS 40081 Düsseldorf Schweidnitzer Str. 41 40231 Düsseldorf Fon 0211 - 26 11 210 Fax 0211 - 26 11 220 eMail [email protected] Gedruckt auf 100% UmweltschutzPapier Stand: Dezember 2008 (5. Auflage) Das Problem ist nicht das gesellschaftliche Symptom. Das Problem ist das ökonomische System. Für eine Welt ohne Ausbeutung und ohne Unterdrückung. Reichtum/Update 2008 Inhalt Zehn Vorbemerkungen ......................................................................................................... 3 Die FORBES-Liste ................................................................................................................... 6 Die MilliardärInnen der Welt ................................................................................................. 7 Russland und China mit den dynamischsten Zuwächsen .................................................. 9 Macht der USA und der G8 geht zu Gunsten BRIC-Staaten zurück .................................... 10 Deutschland innerhalb der G7 nach wie vor auf Platz 2 ..................................................... 10 -

Lesson 1 All Billionaires by Region

RESIDENT BILLIONAIRES BY REGION (WITH AGE AND WEALTH IN $BN) AFRICA Age Wealth County Resident Naguib Sawiris 52 10.0 Egypt Onsi Sawiris 77 5.0 Egypt Johann Rupert & family 56 4.3 South Africa Nassef Sawiris NA 3.9 Egypt Samih Sawiris 50 1.5 Egypt MIDDLE EAST Age Wealth County Resident Nasser Al-Kharafi & family 63 11.5 Kuwait Mohammed Al Amoudi 61 8.0 Saudi Arabia Abdul Aziz Al Ghurair & family 53 8.0 United Arab Emirates Maan Al-Sanea 52 7.5 Saudi Arabia Sulaiman Al Rajhi 87 7.4 Saudi Arabia Nicky Oppenheimer & family 61 5.0 South Africa Saleh Al Rajhi 95 4.4 Saudi Arabia Stef Wertheimer & family 81 4.4 Israel Shari Arison 49 4.3 Israel Lev Leviev 51 4.1 Israel Yitzhak Tshuva 58 4.0 Israel Saleh Kamel 65 3.5 Saudi Arabia Husnu Ozyegin 62 3.5 Turkey Khalid Bin Mahfouz & family 60 3.1 Saudi Arabia Abdulla Al Futtaim NA 3.0 United Arab Emirates Arnon Milchan 62 3.0 Israel Abdullah Al Rajhi NA 2.6 Saudi Arabia Majid Al Futtaim NA 2.5 United Arab Emirates Khalaf Al Habtoor 57 2.5 United Arab Emirates Mehmet Karamehmet 62 2.4 Turkey Age Wealth County Resident Najib Mikati 51 2.3 Lebanon Taha Mikati NA 2.3 Lebanon Erol Sabanci 69 2.1 Turkey Sevket Sabanci 71 2.1 Turkey Sarik Tara 76 2.0 Turkey The DCSF supported Action plan for Geography is delivered jointly and equally by the GA and the RGS-IBG Ahmet Zorlu 62 1.8 Turkey Benny Steinmetz 50 1.7 Israel Bassam Alghanim NA 1.6 Kuwait Kutayba Alghanim 60 1.6 Kuwait Anurag Dikshit 35 1.6 Gibraltar Aydin Dogan 70 1.6 Turkey Ayman Hariri 28 1.6 Saudi Arabia Mohammed Al Rajhi NA 1.5 Saudi Arabia Turgay -

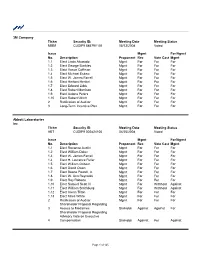

3M Company Ticker Security ID: MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 Issue No

3M Company Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status MMM CUSIP9 88579Y101 05/13/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Linda Alvarado Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect George Buckley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect Vance Coffman Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect Michael Eskew Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect Herbert Henkel Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Edward Liddy Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect Robert Morrison Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Aulana Peters Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Robert Ulrich Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For 3 Long-Term Incentive Plan Mgmt For For For Abbott Laboratories Inc Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ABT CUSIP9 002824100 04/25/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No. Description Proponent Rec Vote Cast Mgmt 1.1 Elect Roxanne Austin Mgmt For For For 1.2 Elect William Daley Mgmt For For For 1.3 Elect W. James Farrell Mgmt For For For 1.4 Elect H. Laurance Fuller Mgmt For For For 1.5 Elect William Osborn Mgmt For For For 1.6 Elect David Owen Mgmt For For For 1.7 Elect Boone Powell, Jr. Mgmt For For For 1.8 Elect W. Ann Reynolds Mgmt For For For 1.9 Elect Roy Roberts Mgmt For For For 1.10 Elect Samuel Scott III Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.11 Elect William Smithburg Mgmt For Withhold Against 1.12 Elect Glenn Tilton Mgmt For For For 1.13 Elect Miles White Mgmt For For For 2 Ratification of Auditor Mgmt For For For Shareholder Proposal Regarding 3 Access to Medicines ShrHoldr Against Against For Shareholder Proposal Regarding Advisory Vote on Executive 4 Compensation ShrHoldr Against For Against Page 1 of 125 Accenture Limited Ticker Security ID: Meeting Date Meeting Status ACN CUSIP9 G1150G111 02/07/2008 Voted Issue Mgmt For/Agnst No.