Cycling Ibgn

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Walking and Jogging for Fitness

GALILEO, University System of Georgia GALILEO Open Learning Materials Nursing and Health Sciences Open Textbooks Nursing and Health Sciences Spring 2018 Walking and Jogging for Fitness Scott Flynn Georgia Highlands College, [email protected] Lisa Jellum Georgia Highlands College, [email protected] Jonathan Howard Georgia Highlands College, [email protected] Althea Moser Georgia Highlands College, [email protected] David Mathis Georgia Highlands College, [email protected] See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/health-textbooks Recommended Citation Flynn, Scott; Jellum, Lisa; Howard, Jonathan; Moser, Althea; Mathis, David; Collins, Christin; Henderson, Sharryse; and Watjen, Connie, "Walking and Jogging for Fitness" (2018). Nursing and Health Sciences Open Textbooks. 3. https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/health-textbooks/3 This Open Textbook is brought to you for free and open access by the Nursing and Health Sciences at GALILEO Open Learning Materials. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nursing and Health Sciences Open Textbooks by an authorized administrator of GALILEO Open Learning Materials. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Scott Flynn, Lisa Jellum, Jonathan Howard, Althea Moser, David Mathis, Christin Collins, Sharryse Henderson, and Connie Watjen This open textbook is available at GALILEO Open Learning Materials: https://oer.galileo.usg.edu/health-textbooks/3 Open Textbook Georgia Highlands College UNIVERSITY SYSTEM OF GEORGIA Scott Flynn, Lisa Jellum, Althea Moser, Jonathan Howard, Sharryse Henderson, Christin Collins, Amanda West, and David Mathis Walking and Jogging for Fitness Walking and Jogging for Fitness Scott Flynn, Lisa Jellum, Althea Moser, Jonathan Howard, Sharryse Henderson, Christin Collins, Amanda West, and David Mathis 1. -

Intro to Track Cycling

Introduction to Track Cycling What to Expect and How to Upgrade Photo: Snowy Mountain Photography Track cycling history ¨ Track racing dates back to the late 1800s and 6-day racing events Velodrome basics ¨ Velodromes can range from less than 200 meters to over 500 meters in length ¨ Wood, concrete, and asphalt 2012 London Olympic Velodrome are common surface materials ¨ Current Olympic velodrome standard is a wood indoor 250 meter velodrome with banking of around 45 degrees ¨ Ed Rudolph Velodrome (aka Northbrook) is a 382 meter asphalt velodrome with banking of around 20 degrees Ed Rudolph Velodrome What are the colored lines on the track? ¨ The ”blue band” or “cote d’azur” marks the track’s inside boundary. Racers may not ride on or below this band. The area below the blue band extending to the grass is called the “apron.” ¨ The black “measurement line” is used to measure the distance around the track. When doing pursuits or time trials, use this line as a guide. ¨ The red “sprinter’s line” defines the border of the sprint lane. The leading rider in this lane is said to “own the lane” and may only be passed by a rider going over on the right. NO PASSING BELOW RIDERS IN THE SPRINTERS LANE. Additionally once a sprint is engaged, a racer who is leading and in the sprinter’s lane can not leave it. ¨ The uppermost blue line is the “stayer’s line” or the relief line. It marks the boundary between faster and slower traffic, with the faster riders below the line and the slower “relief” riders above the line. -

2017 USA Cycling Rulebook

Chapter 7 National Championships 149 7. Championships The following sections apply to National Championships in the disciplines and age groups specified. See section 7J for specific differences between National Championships and State Championships 7A. Organization 7A1. The rights to organize National Championships may be awarded to local Race Directors who meet the requirements established by the CEO. 7A2. Massed start races with fewer than 10 participants may be combined with another category at the discretion of USA Cycling and the Chief Referee with riders being scored separately at the end of the event. 7A3. In National Championship events, the defending National Champion (in that event) shall be given highest priority in call-ups except if the event is run under UCI rules. In track events where heats are required, the defending National Champion must compete in the heats. 7A4. Para-cycling National Championships for cyclists with disabilities may be held in conjunction with other national championships. Classifications of para-cycling riders and regulations of competition will follow the Functional Classification System outlined by the UCI. 7B. National Championship Eligibility 7B1. National Championships are open only to riders who hold USA Cycling rider annual licenses or recognized license from a UCI affiliated federation, and meet other qualifications stated in these rules. (a) National Championships for Junior 17-18, Under 23, and Elites may only be entered by US Citizens with a USA racing nationality. (b) Regardless of any general rule pertaining to National Championship eligibility, any National Championship that is a direct qualifier for the World Championships or Olympic Games may only be entered by riders who are eligible under 150 international regulations to enter those events as part of the U.S. -

The Time-Crunched Cyclist,3Rd Edition, Is Part of the TIME-CRUNCHED ATHLETE™ Series

THE TIME- CRUNCHED3rd Edition CYCLISTRace-Winning Fitness in 6 Hours a Week CHRIS CARMICHAEL and JIM RUTBERG POWERED BY THETIME- CRUNCHED CYCLIST 3rd Edition THETIME- CRUNCHED CYCLIST Race-Winning Fitness in 6 Hours a Week CHRIS CARMICHAEL and JIM RUTBERG BOULDER, COLORADO The Time-Crunched Cyclist, 3rd edition, is part of THE TIME-CRUNCHED ATHLETE™ series. Copyright © 2017 by Chris Carmichael and Jim Rutberg. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, CO 80301–2338 USA VeloPress is the leading publisher of books on endurance sports. Focused on cycling, triathlon, running, swimming, and nutrition/diet, VeloPress books help athletes achieve their goals of going faster and farther. Preview books and contact us at velopress.com. Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Carmichael, Chris, 1960- author. | Rutberg, Jim, author. Title: The time-crunched cyclist: race-winning fitness in 6 hours a week / Chris Carmichael and Jim Rutberg. Description: 3rd edition. | Boulder, Colorado: VeloPress, 2017. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2016055402 (print) | LCCN 2016059236 (ebook) | ISBN 9781937715502 (pbk.: alk. paper) | ISBN 9781937716837 (ebook) Subjects: LCSH: Cycling—Training. | Cyclists—Time management. | Endurance sports— Training. Classification: LCC GV1048 .C38 2009 (print) | LCC GV1048 (ebook) | DDC 796.6—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016055402 This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). -

International OMNIUM

International OMNIUM MEN 1) Flying Lap (against the clock) The International Omnium event 2) 30 km Points Race (15 km for junior men) is a multi-race event for individuals in track 3) Elimination cycling. Historically the omnium has had a 4) 4 km Individual Pursuit (3 km for junior men) variety of formats. Currently, and for the 2012 5) Scratch Race London Olympic Games, the omnium as defined 6) 1km Time trial by the Union Cycliste Internationale (UCI) and consists of six events (both timed individual *Timed events are conducted individually while events and massed start pack races) for men the rest are pack style races. and for women that are conducted over two consecutive days. Ideally, the Omnium event showcases the best all-round, consistent rider -- speed, endurance and savvy race intelligence make up an International Omnium champion. Points are awarded in reverse order for each event within the omnium. The rider who finishes first in an event receives one point, the second rider will gets two points and so on down the placings. The winner is the rider with the lowest total points. If two riders are tied on points, the combined time of the three time trials will be the tie breaker to determine final placing. Also, riders must complete every event in the omnium. So if WOMEN a rider were to crash in an early segment and not 1) Flying Lap (against the clock) make it to the finish, they would be eliminated 2) 20 km Points Race (10 km for junior women) from continuing on in the next portion. -

Modeling Sprint Cycling Using Field-Derived Parameters and Forward Integration

Modeling Sprint Cycling Using Field-Derived Parameters and Forward Integration JAMES C. MARTIN1, A. SCOTT GARDNER2,3, MARTIN BARRAS2, and DAVID T. MARTIN2 1The University of Utah, Department of Exercise and Sport Science, Salt Lake City, UT; 2Australian Institute of Sport, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory, AUSTRALIA; and 3Queensland Academy of Sport, Brisbane, Queensland, AUSTRALIA ABSTRACT MARTIN, J. C., A. S. GARDNER, M. BARRAS, and D. T. MARTIN. Modeling Sprint Cycling Using Field-Derived Parameters and Forward Integration. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc.,Vol. 38, No. 3, pp. 592–597, 2006. We previously reported that a mathematical model could accurately predict steady-state road-cycling power when all the model parameters were known. Application of that model to competitive cycling has been limited by the need to obtain accurate parameter values, the non–steady-state nature of many cycling events, and because the validity of the model at maximal power has not been established. Purpose: We determined whether modeling parameters could be accurately determined during field trials and whether the model could accurately predict cycling speed during maximal acceleration using forward integration. Methods: First, we quantified aerodynamic drag area of six cyclists using both wind tunnel and field trials allowing for these two techniques to be compared. Next, we determined the aerodynamic drag area of three world-class sprint cyclists using the field-test protocol. Track cyclists also performed maximal standing-start time trials, during which we recorded power and speed. Finally, we used forward integration to predict cycling speed from power–time data recorded during the maximal trials allowing us to compare predicted speed with measured speed. -

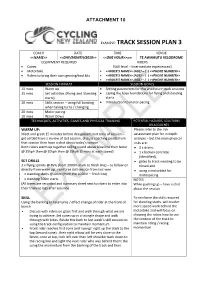

Example: Track Session Plan 3

ATTACHMENT 10 EXAMPLE: TRACK SESSION PLAN 3 COACH DATE TIME VENUE <<NAME>> <<DAY/MONTH/2019>> <<ONE HOUR>>pm TE AWAMUTU VELODROME EQUIPMENT REQUIRED RIDERS Cones [Skill level – Intermediate experienced] Motorbike <<RIDER’S NAME>> (AGE) – ( ) <<PHONE NUMBER>> Riders to bring their own gearing/tool kits <<RIDER’S NAME>> (AGE) – ( ) <<PHONE NUMBER>> <<RIDER’S NAME>> (AGE) – ( ) <<PHONE NUMBER>> SESSION FORMAT SESSION GOALS 15 mins Warm up Setting parameters for this and future track sessions 25 mins Set activities (Flying and Standing Laying the base foundations for flying and standing starts) starts 20 mins Skills session – using full banking Introduction to motor pacing when taking turns / changing 20 mins Motor pacing 10 mins Warm Down TECHNIQUES, ACTIVITIES, GAMES AND PHYSICAL TRAINING POTENTIAL HAZARDS, SOLUTIONS OR ACCIDENTS WARM UP: Please refer to the risk Meet and greet 15 minutes before designated start time of session – assessment plan for in depth get settled have a review of last session, discuss coaching points from analysis – but the main physical that session then have a chat about today’s session risks are: Both riders warm up together rolling round above blue line then faster 3 x drains @ 25kph then @ 30kph then @ 35kph (5 mins at each speed) 1 x broken concrete (identified), SET DRILLS gates to track needing to be 2 x flying sprints @ 85% (from 2000m mark to finish line) – to follow on closed and directly from warm up…reinforce skill session from last wee using a motorbike for • x standing starts @100m (from the 1000m – finish line) motorpacing • x standing 200m starts NOTES (All times are recorded and summary sheet sent to riders to enter into While packing up – have a chat their training logs after session) about the session SKILL To reinforce the skills required Using the banking to take turns / effect change of rider at the front of for standing starts, will involve bunch more speed work behind the • Discuss with riders on grass first and walk through what we are motorbike and will focus on trying to achieve. -

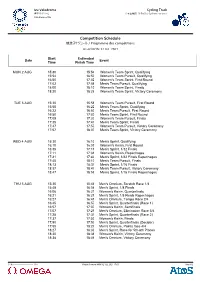

Competition Schedule

Izu Velodrome Cycling Track 伊豆ベロドローム 自転車競技(トラック) / Cyclisme sur piste Vélodrome d'Izu Competition Schedule 競技スケジュール / Programme des compétitions As of MON 12 JUL 2021 at HH:MM Start Estimated Date Event Time Finish Time MON 2 AUG 15:30 15:54 Women's Team Sprint, Qualifying 15:54 16:50 Women's Team Pursuit, Qualifying 16:50 17:02 Women's Team Sprint, First Round 17:02 17:58 Men's Team Pursuit, Qualifying 18:00 18:12 Women's Team Sprint, Finals 18:20 18:28 Women's Team Sprint, Victory Ceremony TUE 3 AUG 15:30 15:58 Women's Team Pursuit, First Round 15:58 16:22 Men's Team Sprint, Qualifying 16:22 16:50 Men's Team Pursuit, First Round 16:50 17:02 Men's Team Sprint, First Round 17:05 17:33 Women's Team Pursuit, Finals 17:35 17:47 Men's Team Sprint, Finals 17:47 17:57 Women's Team Pursuit, Victory Ceremony 17:57 18:07 Men's Team Sprint, Victory Ceremony WED 4 AUG 15:30 16:10 Men's Sprint, Qualifying 16:10 16:35 Women's Keirin, First Round 16:35 17:11 Men's Sprint, 1/32 Finals 17:11 17:31 Women's Keirin, Repechages 17:31 17:43 Men's Sprint, 1/32 Finals Repechages 17:45 18:13 Men's Team Pursuit, Finals 18:13 18:37 Men's Sprint, 1/16 Finals 18:37 18:47 Men's Team Pursuit, Victory Ceremony 18:47 18:59 Men's Sprint, 1/16 Finals Repechages THU 5 AUG 15:30 15:48 Men's Omnium, Scratch Race 1/4 15:48 16:06 Men's Sprint, 1/8 Finals 16:06 16:21 Women's Keirin, Quarterfinals 16:21 16:27 Men's Sprint, 1/8 Finals Repechages 16:27 16:45 Men's Omnium, Tempo Race 2/4 16:45 16:57 Men's Sprint, Quarterfinals (Race 1) 16:57 17:07 Women's Keirin, Semifinals 17:07 -

Using Field Based Data to Model Sprint Track Cycling Performance Hamish A

Ferguson et al. Sports Medicine - Open (2021) 7:20 https://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-021-00310-0 REVIEW ARTICLE Open Access Using Field Based Data to Model Sprint Track Cycling Performance Hamish A. Ferguson1* , Chris Harnish2 and J. Geoffrey Chase1 Abstract Cycling performance models are used to study rider and sport characteristics to better understand performance determinants and optimise competition outcomes. Performance requirements cover the demands of competition a cyclist may encounter, whilst rider attributes are physical, technical and psychological characteristics contributing to performance. Several current models of endurance-cycling enhance understanding of performance in road cycling and track endurance, relying on a supply and demand perspective. However, they have yet to be developed for sprint-cycling, with current athlete preparation, instead relying on measures of peak-power, speed and strength to assess performance and guide training. Peak-power models do not adequately explain the demands of actual competition in events over 15-60 s, let alone, in World-Championship sprint cycling events comprising several rounds to medal finals. Whilst there are no descriptive studies of track-sprint cycling events, we present data from physiological interventions using track cycling and repeated sprint exercise research in multiple sports, to elucidate the demands of performance requiring several maximal sprints over a competition. This review will show physiological and power meter data, illustrating the role of all energy pathways in sprint performance. This understanding highlights the need to focus on the capacity required for a given race and over an event, and therefore the recovery needed for each subsequent race, within and between races, and how optimal pacing can be used to enhance performance. -

Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

Sunday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Barbell Strength Zumba Boot Camp T.B.C. Boot Camp Water Aerobic 5:30-6:30pm / Sarah F. 5:30-6:15am / Allison 5:30-6:30am / Jen 5:30-6:15am / Sandy 5:30-6:30am / Jen Classes H2O M&M Cycle H2O Deep Aqua Challenge New Class/ 7:00-8:00am / Alice 5:30-6:15am / Sarah F. 7:00-8:00am / Alice 7:00-8:00am / Stephanie Instructor/Time Monday Boot Camp T.B.C Aqua Challenge Cycle & Strength Arthritis Foundation 5:30-6:30am / Sandy 8:00-8:55am / Becca 7:00-8:00am / Stephanie 8:00-9:00am / Sara H. Aquatics Program 8:00-9:00am / Marilyn Arthritis Foundation Aqua Challenge Circuit Silver&Fit Excel 9:00-9:55am / Sara J. Aquatics Program 7:00-8:00am / Alice 9:30-10:15am / Kathi Yoga Blast 8:00-9:00am / Marilyn 8:00-8:55am / Sarah F. Arthritis Foundation Core Training SilverSneakers® Yoga Aquatics Program 10:00-10:20am / Sara H. H.I.I.T 10:30-11:15am / Kathi Barbell Strength 8:00-9:00am / Marilyn 8:00-8:55am / Sara J. 9:00-9:55am / Leanne SilverSneakers® Yoga 10:30-11:15am / Kathi H.I.I.T Box, Burn & Sculpt Ultimate Outdoor 5:10-5:55pm / Becca Core Training 8:00-8:55am / Sara J. Workout 10:00-10:20am / Leanne Silver&Fit Excel 9:00-10:00am / Leanne 11:30am-12:15pm / Kathi Stretch & Flow Yoga Yoga Mix 6:00-7:00pm / Sara J. Senior Boot Camp 9:00-9:55am / Sara J. -

Effects of 8-Week Training on Aerobic Capacity and Swimming Per- Formance of Boys Aged 12 Years

Original Paper. Biomedical Human Kinetics, 3, 49 – 52, 2011 DOI: 10.2478/v10101-011-0011-8 Effects of 8-week training on aerobic capacity and swimming per- formance of boys aged 12 years Ryszard Zarzeczny 1, Mariusz Kuberski 1, Agnieszka Deska 1, Dorota Zarzeczna 1, Katarzyna Rydz 1, Anna Lewandowska 2, Tomasz Bałchanowski 3, Janusz Bosiacki 3 1 Institute of Physical Culture and Tourism, Jan Długosz University, Częstochowa; 2 Primary School No. 36, Częstochowa; 3 Primary School No. 48, Częstochowa, Poland Summary Study aim: To assess the effects of 8-week endurance training in swimming on work capacity of boys aged 12 years. Material and methods: The following groups of schoolboys aged 12 years were studied: untrained control (UC; n = 14) and those training swimming for two years. The latter ones were subjected to 8-week training in classical style (CS; n = 10) or free style (FS; n = 13). In all boys maximal oxygen uptake (‡O2max) was determined, and the CS and FS groups were subjected to 6 tests: swimming at 50 and 400 m distances (time recorded) and to 12-min swimming (distance recorded), all by free and classical styles pre- and post-training. From swimming times at 50 and 400 m distances the so-called critical swimming speed (CSS) was computed: CSS = (400 – 50) / (t400 – t50). Results: No training-induced improvement in ‡O2max was noted in any group. Yet, boys subjected to classical style training significantly (p<0.05) improved their free-style swimming velocity at CSS and at the 400-m distance by about 6%, and their heart rate following the 12-min test in classical style decreased by nearly 16% (p<0.001) com- pared with the pre-training values. -

Olympic Sprint, Or Team Sprint

Spectators Summary of Track Cycling Events: (See the USCF rule book or http://www.usacycling.org/ for all the details.) Mass Start or "Scratch" Race: Not surprisingly, all the riders in a Mass Start race start at the same time. The riders all cover the same distance, with the winner being the first rider to cross the finish line at the end of that distance. Although speed is important, tactics and teamwork are equally vital. Groups of riders often take an early lead, and then work together to increase it while their teammates try to block and slow down the "field." On a small track, the leaders may gain an entire lap on the other riders and then join in with the main group again. Points Race: A variation of the Mass Start race, points are awarded to the top placing riders in a series of sprints contested at various intervals during the race. The winner of a Points Race is not necessarily the first to cross the finish line, but rather the rider who has accumulated the most points during the race. Win-And-Out: A variation on the Scratch race where 1st place is decided on the final lap, however, only the winner is finished. In order to secure 2nd place that rider must be first across the line on the next lap. 3rd place is decided on the lap after that. Typically all other places are also decided by this third and final sprint. This makes for interesting tactics. It can be a very hard race if a rider tries gives their all to win only to be forced to continue and try again the next lap.