Documentary Genre“

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Neo-Modern Contemplative and Sublime Cinema Aesthetics in Godfrey Reggio’S Qatsi Trilogy

Art Inquiry. Recherches sur les arts 2016, vol. XVIII ISSN 1641-9278 / e - ISSN 2451-0327219 Kornelia Boczkowska Faculty of English Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań [email protected] SPEEDING SLOWNESS: NEO-MODERN CONTEMPLATIVE AND SUBLIME CINEMA AESTHETICS IN GODFREY REGGIO’S QATSI TRILOGY Abstract: The article analyzes the various ways in which Godfrey Reggio’s experimental documentary films, Koyaanisqatsi (1982), Powaqqatsi (1988) and Naqoyqatsi (2002), tend to incorporate narrative and visual conventions traditionally associated with neo-modern aesthetics of slow and sublime cinema. The former concept, defined as a “varied strain of austere minimalist cinema” (Romney 2010) and characterized by the frequent use of “long takes, de-centred and understated modes of storytelling, and a pronounced emphasis on quietude and the everyday” (Flanagan 2008), is often seen as a creative evolution of Schrader’s transcendental style or, more generally, neo-modernist trends in contemporary cinematography. Although predominantly analyzed through the lens of some common stylistic tropes of the genre’s mainstream works, its scope and framework has been recently broadened to encompass post-1960 experimental and avant-garde as well as realistic documentary films, which often emphasize contemplative rather than slow aspects of the projected scenes (Tuttle 2012). Taking this as a point of departure, I argue that the Qatsi trilogy, despite being classified as largely atypical slow films, relies on a set of conventions which draw both on the stylistic excess of non-verbal sublime cinema (Thompson 1977; Bagatavicius 2015) and on some formal devices of contemplative cinema, including slowness, duration, anti-narrative or Bazinian Realism. -

Tesis: Tlalocan, Paraíso Del Agua. Documental Sobre

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL AUTÓNOMA DE MEXICO POSGRADO EN ARTES Y DISEÑO TLALOCAN, PARAÍSO DEL AGUA. DOCUMENTAL SOBRE ABASTO DE AGUA Y DESAGÜE DE LA CIUDAD DE MÉXICO TESIS QUE PARA OPTAR POR EL GRADO DE: MAESTRO EN CINE DOCUMENTAL PRESENTA: ANDRÉS PULIDO ESTEVA DIRECTOR DE TESIS: DRA. LILIANA CORDERO MARINES (PAD) SINODALES: DR. DIEGO ZAVALA SCHERER (PAD) DRA. ILIANA DEL CARMEN ORTEGA VACA (PAD) DR. ANTONIO DEL RIVERO HERRERA (PAD) CINEASTA MARIA DEL CARMEN DE LARA RANGEL (PAD) Méxcio D.F. Enero, 2016 UNAM – Dirección General de Bibliotecas Tesis Digitales Restricciones de uso DERECHOS RESERVADOS © PROHIBIDA SU REPRODUCCIÓN TOTAL O PARCIAL Todo el material contenido en esta tesis esta protegido por la Ley Federal del Derecho de Autor (LFDA) de los Estados Unidos Mexicanos (México). El uso de imágenes, fragmentos de videos, y demás material que sea objeto de protección de los derechos de autor, será exclusivamente para fines educativos e informativos y deberá citar la fuente donde la obtuvo mencionando el autor o autores. Cualquier uso distinto como el lucro, reproducción, edición o modificación, será perseguido y sancionado por el respectivo titular de los Derechos de Autor. ÍNDICE Agradecimientos Introducción ··························································································· 4 ································································································· 6 El problema y las formas de ilustrarlo ··················································· 7 Los objetivos y la perspectiva ····························································· -

General Considerations

General considerations Documentary is not reality. Documentary films are constructions: Building blocks: Scenes. Director: Creates shapes and forms. Arquitect? Filmmakers create a time experience. A basic aspect is how time lives and passes in your film. Time as a structural element. General considerations John Grierson (the father of documentary) defined documentary as: CREATIVE TREATMENT OF ACTUALITY. You are a director, a subjectivity. Not a camera. You are not there to record reality. Interpreting reality is key. Types of Documentaries Expository Documentaries – aims to persuade and inform, often through “Voice of God” narration. EX: The City (Ralph Steiner, WilliardVan Dyke, 1939) https://archive.org/details/0545_City_The Observational Documentaries – “simply” observes the world EX: Edificio España (Victor Moreno, 2012) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FEIv2cYiIK4 EX: Nice Time (Alain Tanner, Claud Goretta, 1957) Reflexive Documentaries – includes the filmmaker but focuses solely on the act of making the film. EX: Chronicle of a Summer (Jean Rouch, 1960) https://mubi.com/es/films/chronicle-of-a-summer/trailer Types of Documentaries Poetic Documentaries – focuses on experiences and images to create a feeling rather than a truth. EX: Rain (Joris Ivens, 1929) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eNNI7knvh8o Participatory Documentaries – includes the filmmaker who influences the major actions of the narrative. EX: The Lift (Marc Isaac, 2001) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FJNAvyLCTik Performative Documentaries – Performative subjects (Unmade Beds) or the “Michael Moore” style that put the filmmaker as central performer in the film. EX: Unmade Beds (Nicholas Barker, 1997) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rqOrER1mQ9o EX: The Leader, His Driver and The Driver’s Wife (Nick Broomfield, 1991) - {Eugène Terre'Blanche} https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WJy9MuYcIBM&feature=emb_logo What is a creative documentary? By Noé Mendelle Telling a story with reality that involves emotions rather than information. -

Art and Technology Between the Usa and the Ussr, 1926 to 1933

THE AMERIKA MACHINE: ART AND TECHNOLOGY BETWEEN THE USA AND THE USSR, 1926 TO 1933. BARNABY EMMETT HARAN PHD THESIS 2008 DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY OF ART UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON SUPERVISOR: PROFESSOR ANDREW HEMINGWAY UMI Number: U591491 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591491 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 I, Bamaby Emmett Haran, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 3 ABSTRACT This thesis concerns the meeting of art and technology in the cultural arena of the American avant-garde during the late 1920s and early 1930s. It assesses the impact of Russian technological Modernism, especially Constructivism, in the United States, chiefly in New York where it was disseminated, mimicked, and redefined. It is based on the paradox that Americans travelling to Europe and Russia on cultural pilgrimages to escape America were greeted with ‘Amerikanismus’ and ‘Amerikanizm’, where America represented the vanguard of technological modernity. -

LOVERS of CINEMA: the FIRST AMERICAN FILM AVANT-GARDE 1919-1945 Edited by Jan-Christopher Horak Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, 404 Pp

REVIE W -ESSAY LOVERS OF CINEMA: THE FIRST AMERICAN FILM AVANT-GARDE 1919-1945 Edited by Jan-Christopher Horak Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1995, 404 pp. istories of the avant-garde cinema ordinarily divide the field of study H into two major phases, the first (European) avant-garde of the twen - ties and the second (American) avant-garde. This division of the avant- garde into two phases has served polemical purposes. American art has long been possessed by an aspiration to distinguish itself from European models. Several of the New England Transcendentalists, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, advanced claims that American art had distinctive characteristics. The civilized (European) world impedes efforts to contact the self, they argued; withdrawing into the embrace of nature assists those efforts. This portrayal of humans’ rela - tionship with the natural world as redemptive is a key theme of American documentary film. It is also the ground for the idea of the redemptive power of direct contact with the given thing, which one discovers anew once the deadening effects of historically induced preconceptions have been set aside. The very project of a historiographical approach to American avant- garde film that is based on Emersonian ideas of American particularism is what Jan-Christopher Horak’s anthology puts at stake. 1 Suppose, for exam - ple, there were a strong avant-garde cinema in 1920s America, that devel - oped with some measure of independence from European models (as Strand and Sheeler’s Manhatta [1921] and Ralph Steiner’s H2O [1929]—just to choose two works that are pretty familiar—suggest). -

Report to the U. S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2009

Report to the U.S. Congress for the Year Ending December 31, 2009 Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage Created by the U.S. Congress to Preserve America’s Film Heritage April 12, 2010 Dr. James H. Billington The Librarian of Congress Washington, D.C. 20540-1000 Dear Dr. Billington: In accordance with The Library of Congress Sound Recording and Film Preservation Programs Reauthorization Act of 2008 (Public Law 110-336), I submit to the U.S. Congress the 2009 Report of the National Film Preservation Foundation. The NFPF presents this Report proud of deeds accomplished but humbled by the work still left to do. When the foundation started its grant program in 1998, only a handful of institutions had the resources to preserve historically significant American films in their collections. Now, thanks to federal funding secured through the Library of Congress as well as the support of the entertainment industry, 202 archives, libraries, and museums from coast to coast are saving American films and sharing them with the public. These efforts have rescued 1,562 works that might otherwise have been lost—newsreels, documentaries, silent-era features, avant-garde films, home movies, industrials, and independent productions. Films preserved through the NFPF are now used widely in education and reach audiences everywhere through theatrical exhibition, television, video, and the Internet. More culturally significant American films are being rediscovered every day—both here and abroad. Increasingly preservationists are finding that archives in other countries hold a key to unlocking America’s “lost” silent film heritage. -

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases PRACTICE RESEARCH MAX TOHLINE ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Max Tohline The genealogies of the supercut, which extend well past YouTube compilations, back Independent scholar, US to the 1920s and beyond, reveal it not as an aesthetic that trickled from avant-garde [email protected] experimentation into mass entertainment, but rather the material expression of a newly-ascendant mode of knowledge and power: the database episteme. KEYWORDS: editing; supercut; compilation; montage; archive; database TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Tohline, M. 2021. A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases. Open Screens, 4(1): 8, pp. 1–16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/os.45 Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 2 Full Transcript: https://www.academia.edu/45172369/Tohline_A_Supercut_of_Supercuts_full_transcript. Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 3 RESEARCH STATEMENT strong patterning in supercuts focuses viewer attention toward that which repeats, stoking uncritical desire for This first inklings of this video essay came in the form that repetition, regardless of the content of the images. of a one-off blog post I wrote seven years ago (Tohline While critical analysis is certainly possible within the 2013) in response to Miklos Kiss’s work on the “narrative” form, the supercut, broadly speaking, naturally gravitates supercut (Kiss 2013). My thoughts then comprised little toward desire instead of analysis. more than a list; an attempt to add a few works to Armed with this conclusion, part two sets out to the prehistory of the supercut that I felt Kiss and other discover the various roots of the supercut with this supercut researchers or popularizers, like Tom McCormack desire-centered-ness, and other pragmatics, as a guide. -

Finding Aid for the Ralph Steiner Archive

Center for Creative Photography The University of Arizona 1030 N. Olive Rd. P.O. Box 210103 Tucson, AZ 85721 Phone: 520-621-6273 Fax: 520-621-9444 Email: [email protected] URL: http://creativephotography.org Finding aid for the Ralph Steiner Miscellaneous Collection, 1899-1986 AG 142 Finding aid updated by Paige Hilman, 2018 AG 142: Ralph Steiner Misc. Collection - page 2 Ralph Steiner Miscellaneous Collection, 1899-1986 AG 142 Creator This is an artificial collection, compiled to document the career of Steiner from a variety of perspectives. Abstract Miscellaneous papers and camera equipment documenting the career of Ralph Steiner, 1899-1986, photographer and filmmaker. Quantity/ Extent 1 linear foot Language of Materials English Biographical/ Historical Note Ralph Steiner studied photography at Dartmouth College in New Hampshire and at the Clarence White School from 1921 to 1922. With White's assistance, Steiner got a job making photogravure plates at the Manhattan Photogravure Company, where Alfred Stieglitz's Camera Work was printed. After about a year, he quit to become a freelance advertising and magazine photographer. Steiner began to make films in the late 1920s. In 1936 he worked with Paul Strand on The Plow That Broke the Plains, Pare Lorentz's documentary film about the dust bowl storms. Two years later, Steiner and Willard Van Dyke founded American Documentary Films, Inc., and collaborated on The City, a critically acclaimed film about New York. Steiner moved to Hollywood in the 1940s but returned to New York in 1948. There he continued to freelance both as a photographer and cameraman and occasionally taught students. -

1 NEW DEAL FILMS Living New Deal Project May 2013 the Following List of New Deal Films Provides Information Regarding One Hundre

NEW DEAL FILMS Living New Deal Project May 2013 The following list of New Deal films provides information regarding one hundred unique titles, with links to online footage wherever possible. With a few exceptions, all of the films collected below were produced by and for New Deal agencies and programs as promotional, documentary, or training films. Each entry aims to offer general information about each title, including which New Deal agency sponsored the film and a brief description of its content. Rather than a comprehensive catalog, this list sketches out in broad strokes the rich body of cinematic work supported by New Deal programs. The films on this list highlight the direct fruits of a public commitment to employment relief and the arts. Researchers interested in further exploring New Deal era films – including those related to or about the New Deal though not explicitly produced by or for New Deal agencies – are encouraged to pursue the resources included in the reference section at the end of the list. Special thanks goes to Megan and Rick Prelinger of the Prelinger Library, where the majority of research for this project was performed. Research by John Elrick for the Living New Deal – http://livingnewdeal.org. 1.) Alabama Highlands (1937, 11 min) [Development of State Parks around Birmingham, Alabama] Agency Sponsors: U.S. Department of the Interior, CCC Reference: D. Cook, E. Rahbek-Smith, Educational Film Catalog, Supplement to the Second Edition. New York: H.W. Wilson Co., 1942. Film Link: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-ArpLe_A0zk 2.) A Better Minnesota (1937, 9 min) [WPA efforts in Minnesota] Agency Sponsor: WPA Reference: Larry N. -

A Corpus in First-Person: Weegee and the Performance of the Self

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works School of Arts & Sciences Theses Hunter College Spring 5-9-2017 A Corpus in First-Person: Weegee and the Performance of the Self Emily Annis CUNY Hunter College How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/hc_sas_etds/153 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] A Corpus in First-Person: Weegee and the Performance of the Self by Emily Annis Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History, Hunter College The City University of New York 2017 Thesis Sponsor: May 9, 2017 Dr. Maria Antonella Pelizzari Date Signature May 9, 2017 Dr. Howard Singerman Date Signature of Second Reader TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations……………………………………………………………………………...…ii Introduction…………………………………………………………………………………..…....1 Chapter 1: From Low to High: The Project of Weegee’s Self-Fashioning………………...…......9 Chapter 2: The “I” and Naked City…………………………………….………………………...31 Chapter 3: The Subjugation of Weegee’s People ……………………………………..………...52 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………………….60 Bibliography……………………………………………………………………………………..62 Illustrations………………………………………………………………….…………………...66 i List of Illustrations Figure 1: “Speaking of Pictures...A Free Lance Photographs the News,” Life vol. 2, no. 15 (April 12, 1937): 8-9, 11 Figure 2: Installation view of “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” at the Photo League, New York, 1941. International Center of Photography Figure 3: Installation view of “Weegee: Murder Is My Business” at the Photo League, New York, 1941. -

SFSFF 2018 Program Book

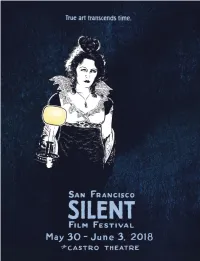

elcome to the San Francisco Silent Film Festival for five days and nights of live cinema! This is SFSFFʼs twenty-third year of sharing revered silent-era Wmasterpieces and newly revived discoveries as they were meant to be experienced—with live musical accompaniment. We’ve even added a day, so there’s more to enjoy of the silent-era’s treasures, including features from nine countries and inventive experiments from cinema’s early days and the height of the avant-garde. A nonprofit organization, SFSFF is committed to educating the public about silent-era cinema as a valuable historical and cultural record as well as an art form with enduring relevance. In a remarkably short time after the birth of moving pictures, filmmakers developed all the techniques that make cinema the powerful medium it is today— everything except for the ability to marry sound to the film print. Yet these films can be breathtakingly modern. They have influenced every subsequent generation of filmmakers and they continue to astonish and delight audiences a century after they were made. SFSFF also carries on silent cinemaʼs live music tradition, screening these films with accompaniment by the worldʼs foremost practitioners of putting live sound to the picture. Showcasing silent-era titles, often in restored or preserved prints, SFSFF has long supported film preservation through the Silent Film Festival Preservation Fund. In addition, over time, we have expanded our participation in major film restoration projects, premiering four features and some newly discovered documentary footage at this event alone. This year coincides with a milestone birthday of film scholar extraordinaire Kevin Brownlow, whom we celebrate with an onstage appearance on June 2. -

Film As Artifact the City (1939) Howard Gillette, Jr

film as artifact the city (1939) howard gillette, jr. Although a great deal has been written about the use of film as his torical evidence, scholars still have much to explore in the relationship of the medium to patterns of American culture. Too often historians, with their emphasis on what happened in the past, have consigned the film to a supplemental role in documenting the progression of important events. Film specialists, on the other hand, have tended to minimize considera tion of the complex historical circumstances which help shape both film content and technique. Like any other survival from the past—a manu script, a piece of pottery or a building—film conveys a message to the historian, but one which necessitates careful interpretation both of the medium itself and its context. American studies, with its estab FIGURE ONE (above) : One of many shots of prohibitory signs. lished concern for the FIGURE TWO (below) : Children brought up in slums are contrasted inter-relationship of to children in the new garden cities (see Figure Five, page 79). The Museum of Modern Art/Film Stills Archive, 21 W. 53rd Street, any artistic medium New York City. with the historical circumstances out of which it emerged, should take the lead in filling this void in film scholarship. Circumstances sur rounding the appear ance of The City—at the confluence of im portant new tradi tions in American documentary film and urban theory— provide an excellent opportunity to illustrate the importance of film as an historical artifact. Typically, published references to the film, in cluding the most significant ones in Richard Barsam's Nonaction Film and Mel Scott's American City Planning,1 examine only the barest details of the relation between film technique and urban planning.