Text Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Songs by Artist

Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title &, Caitlin Will 12 Gauge Address In The Stars Dunkie Butt 10 Cc 12 Stones Donna We Are One Dreadlock Holiday 19 Somethin' Im Mandy Fly Me Mark Wills I'm Not In Love 1910 Fruitgum Co Rubber Bullets 1, 2, 3 Redlight Things We Do For Love Simon Says Wall Street Shuffle 1910 Fruitgum Co. 10 Years 1,2,3 Redlight Through The Iris Simon Says Wasteland 1975 10, 000 Maniacs Chocolate These Are The Days City 10,000 Maniacs Love Me Because Of The Night Sex... Because The Night Sex.... More Than This Sound These Are The Days The Sound Trouble Me UGH! 10,000 Maniacs Wvocal 1975, The Because The Night Chocolate 100 Proof Aged In Soul Sex Somebody's Been Sleeping The City 10Cc 1Barenaked Ladies Dreadlock Holiday Be My Yoko Ono I'm Not In Love Brian Wilson (2000 Version) We Do For Love Call And Answer 11) Enid OS Get In Line (Duet Version) 112 Get In Line (Solo Version) Come See Me It's All Been Done Cupid Jane Dance With Me Never Is Enough It's Over Now Old Apartment, The Only You One Week Peaches & Cream Shoe Box Peaches And Cream Straw Hat U Already Know What A Good Boy Song List Generator® Printed 11/21/2017 Page 1 of 486 Licensed to Greg Reil Reil Entertainment Songs by Artist Karaoke by Artist Title Title 1Barenaked Ladies 20 Fingers When I Fall Short Dick Man 1Beatles, The 2AM Club Come Together Not Your Boyfriend Day Tripper 2Pac Good Day Sunshine California Love (Original Version) Help! 3 Degrees I Saw Her Standing There When Will I See You Again Love Me Do Woman In Love Nowhere Man 3 Dog Night P.S. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

GOOGLE LLC V. ORACLE AMERICA, INC

(Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2020 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus GOOGLE LLC v. ORACLE AMERICA, INC. CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FEDERAL CIRCUIT No. 18–956. Argued October 7, 2020—Decided April 5, 2021 Oracle America, Inc., owns a copyright in Java SE, a computer platform that uses the popular Java computer programming language. In 2005, Google acquired Android and sought to build a new software platform for mobile devices. To allow the millions of programmers familiar with the Java programming language to work with its new Android plat- form, Google copied roughly 11,500 lines of code from the Java SE pro- gram. The copied lines are part of a tool called an Application Pro- gramming Interface (API). An API allows programmers to call upon prewritten computing tasks for use in their own programs. Over the course of protracted litigation, the lower courts have considered (1) whether Java SE’s owner could copyright the copied lines from the API, and (2) if so, whether Google’s copying constituted a permissible “fair use” of that material freeing Google from copyright liability. In the proceedings below, the Federal Circuit held that the copied lines are copyrightable. -

United States Court of Appeals for the SECOND CIRCUIT >> >>

Case 15-1815, Document 33, 01/12/2016, 1682741, Page1 of 265 15-1815-CR IN THE United States Court of Appeals FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT >> >> UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, Appellee, v. ROSS WILLIAM ULBRICHT, AKA DREAD PIRATE ROBERTS, AKA SILK ROAD, AKA SEALED DEFENDANT 1, AKA DPR, Defendant-Appellant. On Appeal from the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (New York City) APPENDIX VOLUME III OF VI Pages A515 to A768 MICHAEL A. LEVY JOSHUA L. DRATEL, P.C. SERRIN A. TURNER Attorneys for Defendant-Appellant ASSISTANT UNITED STATES ATTORNEYS 29 Broadway, Suite 1412 UNITED STATES ATTORNEY’S OFFICE FOR THE New York, New York 10006 SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK 212-732-0707 Attorneys for Appellee 1 Saint Andrew’s Plaza New York, New York 10007 212-637-2346 Case 15-1815, Document 33, 01/12/2016, 1682741, Page2 of 265 Table of Contents Page Volume I District Court Docket Entries ................................................................. A1 Sealed Complaint, dated September 27, 2013 ....................................... A48 Exhibit A to Complaint - Printout of Silk Road Anonymous Market Search ................... A81 Exhibit B to Complaint - Printout of Silk Road Anonymous Market High Quality #4 Heroin All Rock ..................................................... A83 Indictment, entered February 4, 2014 .................................................... A87 Opinion and Order of the Honorable Katherine B. Forrest, dated July 9, 2014 ........................................................................... A99 Superseding Indictment, entered August 21, 2014 ............................... A150 Order of the Honorable Katherine B. Forrest, dated October 7, 2014 .................................................................... A167 Letter from Joshua L. Dratel to the Honorable Katherine B. Forrest, dated October 7, 2014 ................................. A169 Endorsed Letter from Joshua L. Dratel to the Honorable Katherine B. -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

The Little Prince'

The Bomoo.com Ebook of English Series Antoine de Saint-Exupér y The L ittle Prince 2003. 7 ANNOUNCEMENT This ebook is designed and produced by Bomoo.com, which collected the content from Internet. You can distribute it free, but any business use and any edit are prohibited. The original author is the copyright holder of all relating contents. You are encouraged to send us error messages and suggestions about this ebook to [email protected]. More materials can be found at the site http://www.bomoo.com. The America Edition’s Cover SAINT-EXUPÉRY, Antoine de (1900-44). An adventurous pilot and a lyrical poet, Antoine de Saint-Exupéry conveyed in his books the solitude and mystic grandeur of the early days of flight. He described dangerous adventures in the skies and also wrote the whimsical children's fable 'The Little Prince'. Antoine-Marie-Roger de Saint-Exupéry was born on June 29, 1900, in Lyon, France. In the 1920s he helped establish airmail routes overseas. During World War II he flew as a military reconnaissance pilot. After the Germans occupied France in 1940, he escaped to the United States. He rejoined the air force in North Africa in 1943. During what was to have been his final reconnaissance mission over the Mediterranean Sea, he died when his plane was shot down on July 31, 1944. Saint-Exupery's first book, 'Southern Mail', was about the life and death of an airmail pilot. It was published in French in 1929. Other books include 'Night Flight' (1931), about the first airline pilots, and 'Wind, Sand, and Stars' (1939), in which he describes his feelings during flights over the desert. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

Adventuring with Books: a Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. the NCTE Booklist

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 311 453 CS 212 097 AUTHOR Jett-Simpson, Mary, Ed. TITLE Adventuring with Books: A Booklist for Pre-K-Grade 6. Ninth Edition. The NCTE Booklist Series. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, Ill. REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0078-3 PUB DATE 89 NOTE 570p.; Prepared by the Committee on the Elementary School Booklist of the National Council of Teachers of English. For earlier edition, see ED 264 588. AVAILABLE FROMNational Council of Teachers of English, 1111 Kenyon Rd., Urbana, IL 61801 (Stock No. 00783-3020; $12.95 member, $16.50 nonmember). PUB TYPE Books (010) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF02/PC23 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Annotated Bibliographies; Art; Athletics; Biographies; *Books; *Childress Literature; Elementary Education; Fantasy; Fiction; Nonfiction; Poetry; Preschool Education; *Reading Materials; Recreational Reading; Sciences; Social Studies IDENTIFIERS Historical Fiction; *Trade Books ABSTRACT Intended to provide teachers with a list of recently published books recommended for children, this annotated booklist cites titles of children's trade books selected for their literary and artistic quality. The annotations in the booklist include a critical statement about each book as well as a brief description of the content, and--where appropriate--information about quality and composition of illustrations. Some 1,800 titles are included in this publication; they were selected from approximately 8,000 children's books published in the United States between 1985 and 1989 and are divided into the following categories: (1) books for babies and toddlers, (2) basic concept books, (3) wordless picture books, (4) language and reading, (5) poetry. (6) classics, (7) traditional literature, (8) fantasy,(9) science fiction, (10) contemporary realistic fiction, (11) historical fiction, (12) biography, (13) social studies, (14) science and mathematics, (15) fine arts, (16) crafts and hobbies, (17) sports and games, and (18) holidays. -

The Teen Years Explained: a Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development

T HE T EEN Y THE TEEN YEARS EARS EXPLAINED EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED: HEALTHY A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT ADOLESCENT : By Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT A GUIDE TO HEALTHY DEVELOPMENT The teen years are a time of opportunity, not turmoil. The Teen Years Explained: A Guide to Healthy Adolescent Development describes the normal physical, cognitive, emotional and social, sexual, identity formation, and spiritual changes that happen during adolescence and how adults can promote healthy development. Understanding these changes—developmentally, what is happening and why—can help both adults and teens enjoy the second decade of life. The Guide is an essential resource for all people who work with young people. © 2009 Center for Adolescent Health at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Printed in the United States of America. Printed and distributed by the Center for Adolescent Health at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. Clea McNeely & Jayne Blanchard For additional information about the Guide and to order additional copies, please contact: Center for Adolescent Health Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health 615 N. Wolfe St., E-4543 Baltimore, MD 21205 www.jhsph.edu/adolescenthealth 410-614-3953 ISBN 978-0-615-30246-1 Designed by Denise Dalton of Zota Creative Group Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH and Jayne Blanchard THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED A GUIDE TO HEALTHY ADOLESCENT DEVELOPMENT By Clea McNeely, MA, DrPH Jayne Blanchard With a foreword by Nicole Yohalem Karen Pittman iv THE TEEN YEARS EXPLAINED CONTENTS About the Center for Adolescent Health ........................................ -

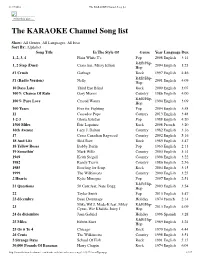

The KARAOKE Channel Song List

11/17/2016 The KARAOKE Channel Song list Print this List ... The KARAOKE Channel Song list Show: All Genres, All Languages, All Eras Sort By: Alphabet Song Title In The Style Of Genre Year Language Dur. 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's Pop 2008 English 3:14 R&B/Hip- 1, 2 Step (Duet) Ciara feat. Missy Elliott 2004 English 3:23 Hop #1 Crush Garbage Rock 1997 English 4:46 R&B/Hip- #1 (Radio Version) Nelly 2001 English 4:09 Hop 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind Rock 2000 English 3:07 100% Chance Of Rain Gary Morris Country 1986 English 4:00 R&B/Hip- 100% Pure Love Crystal Waters 1994 English 3:09 Hop 100 Years Five for Fighting Pop 2004 English 3:58 11 Cassadee Pope Country 2013 English 3:48 1-2-3 Gloria Estefan Pop 1988 English 4:20 1500 Miles Éric Lapointe Rock 2008 French 3:20 16th Avenue Lacy J. Dalton Country 1982 English 3:16 17 Cross Canadian Ragweed Country 2002 English 5:16 18 And Life Skid Row Rock 1989 English 3:47 18 Yellow Roses Bobby Darin Pop 1963 English 2:13 19 Somethin' Mark Wills Country 2003 English 3:14 1969 Keith Stegall Country 1996 English 3:22 1982 Randy Travis Country 1986 English 2:56 1985 Bowling for Soup Rock 2004 English 3:15 1999 The Wilkinsons Country 2000 English 3:25 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue Pop 2007 English 2:51 R&B/Hip- 21 Questions 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg 2003 English 3:54 Hop 22 Taylor Swift Pop 2013 English 3:47 23 décembre Beau Dommage Holiday 1974 French 2:14 Mike WiLL Made-It feat. -

But It's Not Fair

But It’s Not Fair 1 ANEETA PREM 2 But It’s Not Fair ANEETA PREM 3 4 But It’s Not Fair This novel is entirely a work of fiction. The names, characters and incidents portrayed in it are the work of the author’s imagination. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events or localities is entirely coincidental. PREM PUBLISHING First published in Great Britain by Prem Publishing Copyright © Aneeta Prem 2011 Aneeta Prem asserts her moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record of this book is available from the British Library Edited by Jacqueline Burns Text by Two Associates Cover Design by Trident Marketing Anglia Ltd Illustrations by Kati Teague Set in Avenir Printed and bound in Great Britain by Trident Marketing Anglia Ltd. 978-0-9569751-0-2 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publishers. 5 DEDICATION I dedicate this book to the most inspirational being I have ever known, Author, College Principal, Dad, Chandra Shekhar Prem I wish you could have been here to share this. I miss you every day and I know your love is still with me. My Darling Mum, Savita Prem Thank you for being there, not only the Best Mum in the World, but also for supporting all my ideals and always being there for me. Vineeta Prem Thornhill, best friend Beautiful inside and out. -

Battle Ground : a Novel of the Dresden Files / Jim Butcher

ALSO BY JIM BUTCHER THE DRESDEN FILES STORM FRONT FOOL MOON GRAVE PERIL SUMMER KNIGHT DEATH MASKS BLOOD RITES DEAD BEAT PROVEN GUILTY WHITE NIGHT SMALL FAVOR TURN COAT CHANGES GHOST STORY COLD DAYS SKIN GAME PEACE TALKS SIDE JOBS (Anthology) BRIEF CASES (Anthology) THE CINDER SPIRES THE AERONAUT’S WINDLASS THE CODEX ALERA FURIES OF CALDERON ACADEM’S FURY CURSOR’S FURY CAPTAIN’S FURY PRINCEPS’ FURY FIRST LORD’S FURY SHADOWED SOULS (EDITED BY JIM BUTCHER AND KERRIE L. HUGHES) ACE Published by Berkley An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC penguinrandomhouse.com Copyright © 2020 by Jim Butcher “Christmas Eve” copyright © 2018 by Jim Butcher Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader. ACE is a registered trademark and the A colophon is a trademark of Penguin Random House LLC. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Butcher, Jim, 1971– author. Title: Battle ground : a novel of the Dresden files / Jim Butcher. Description: First Edition. | New York : Ace, [2020] | Series: The Dresden files Identifiers: LCCN 2020008653 (print) | LCCN 2020008654 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593199305 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593199329 (ebook) Subjects: GSAFD: Fantasy fiction. Classification: LCC PS3602.U85 B88 2020 (print) | LCC PS3602.U85 (ebook) | DDC 813/.6—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008653 LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020008654 Jacket art by Chris McGrath Jacket design by Adam Auerbach This is a work of fiction.