Lifelong Learning in Parasport Coaching

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

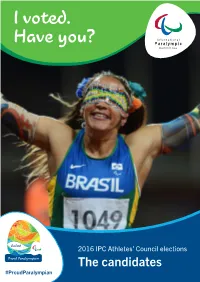

2016 06 Candidate PDF.Indd

I voted. Have you? 2016 IPC Athletes’ Council elections The candidates #ProudParalympian Who is the IPC Athletes’ Council? The IPC Athletes’ Council is the collective voice of Paralympic athletes within the IPC and the greater Paralympic Movement. As the liaison between IPC decision-makers and Paralympic athletes, the IPC Athletes’ Council works to provide effective input into decision-making at all levels of the organisa- tion. To this end, the IPC Athletes’ Council works to ensure effective athlete representation on all IPC committees and commissions as well as to create other opportunities for athlete representation both within and outside the IPC. For example, the IPC Athletes’ Council enjoys cross representation with the IOC Athletes’ Commission. 2016 IPC Athletes’ Council elections Elections for the six summer sport representatives on the Athletes’ Council will take place between 5 and 16 September, in the #ProudParalympian space of the Athletes’ Dining Hall in the Paralympic Village. All “Aa” accredited athletes are entitled to vote. Athletes must vote for six candidates (not more not less). The IPC Electoral Commission is composed of the following individuals: ▪ Linda Mastandrea (IPC Legal and Ethics Committee Chairperson) – Electoral Commission Chairperson ▪ Mark Copeland (IPC Legal and Ethics Committee Member) ▪ Martin Mansell (former Chairperson IPC Athletes’ Council) To cast your vote, you simply need to: 1. Show your accreditation card at the voting station. Your card will be checked in the Voting Registration System and it will be checked that you are eligible to vote. 2. In the voting booth, follow the instructions of the electronic voting system. Please note that athletes who require assistance may select an assistant of their choice to complete the voting process. -

Editorial Style from a to Z April 2012

Contents A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z London 2012 Editorial style from A to Z April 2012 The aim of this editorial style guide is to If you are giving this guide to anyone Introduction help everyone write about London 2012 externally, please inform LOCOG’s with clarity and consistency. The guide Editorial Services team or the ODA’s includes practical information to ensure Marketing team so we can let them writers prepare accurate content in the know when it is reissued. If you have most suitable style. any queries that are not covered by the guide, please let us know so we The guide is arranged alphabetically for can include them in future editions. ease of use, with simple navigational tools to help you find what you’re looking Working together, we will develop for. Clicking on the letters across the top effective and accessible content that of every page will take you to the first will help make London 2012 an page of each section. In addition, each incredible experience for all audiences. entry on the contents page is a link, and there are cross-references with links to other sections throughout the guide. As our organisation develops, so our style guide needs to be flexible and adaptable. For this reason, we will be regularly updating this document. Please ensure that you have the latest version. This document and the official Emblems of the London 2012 Games are © London Organising Committee of the Olympic Games and Paralympic Games Limited 2007–2012. -

Classification of Disabled Athletes: (Dis)Empowering the Paralympic

The Tail is Wagging the Dog: Body Culture, Classification and the Paralympic Movement For consideration for the special issue of Ethnography on physical culture Submitted by Dr. P. David Howe Academic Associate Peter Harrison Centre for Disability Sport Lecturer in the Sociology of Sport School of Sport and Exercise Sciences Loughborough University Loughborough UK LE11 3TU http://www.lboro.ac.uk/departments/sses/contact/staff/pdh.html ph. +44 (0)1509 226389 fax. +44 (0)1509 226301 [email protected] 1 Abstract. The rules and regulations regarding the classification process through which athletes must be vetted to determine eligibility for Paralympic competition have been transformed drastically over the last two decades. A complex classification system initially developed by the International Organizations of Sport for the Disabled (IOSD) has been the distinctive feature of the Paralympic movement over this period. Key consideration must be given to the equitable nature of any classification system imposed by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC) in order to comply with the ideology of Paralympism. Paralympism is manifest in the dictum of the Paralympic movement ‘empower, inspire and achieve’. Using ethnographic data obtained while a Paralympic athlete this paper explores recent debates within the sport of athletics surrounding classification. This is achieved by highlighting the process of classification and how as a result of this process some bodies are celebrated and others are not within a sporting culture established as a ghetto for imperfection. KEY WORDS: Paralympism, ethics, classification, athletics, habitus This paper highlights the importance of body culture in the transforming of the Paralympic movement by examining data collected ethnographically by an anthropologist who was both athlete and administrator within elite sporting practice for the disabled1. -

Swimming Into Olympism and Saving Lives

SWIMMING INTO OLYMPISM AND SAVING LIVES Stacy L. Schaetz Master dissertation submitted to the professional body for the partial fulfillment of obligations for the awarding of a post-graduate title in the Post-graduate Programme, "Organization and Management of Olympic Events" of the University of the Peloponnese, in the branch of Olympic Education. Sparta 2016 Approved by the Professor body: 1st Supervisor: Elia Chatzigianni Prof. UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE, GREECE 2nd Supervisor: Kostas Georgiadis Prof. UNIVERSITY OF PELOPONNESE, GREECE 3rd Supervisor: Ourania Vrondou, Prof. UNIVERSITY. OF PELOPONNESE, GREECE Copyright © Stacy Lorraine Schaetz, 2016. All rights reserved. Swimming into Olympism and Saving Lives CONTENTS CONTENTS …………………………………………………………………………..i SUMMARY…….……………………………………………………………..............iii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………………………..iv INTRODUCTION………………………………………………………………...…..1 CHAPTER I -SWIMMING: AN HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE……………………7 Gender Equality……………………………………………………...……………….10 Swimming Pools………………………………………………………………………12 CHAPTER II-DROWNING: A SILENT KILLER……………………………….......15 Drowning Fears…………………………………………………………………….....23 The Law of Buoyancy…………………………………………………………………27 CHAPTER III-SWIMMING: DIVERSITY IN AQUATICS …………….…………29 The Color of Swimming……………………………………..………………………..29 Paralympic Swimming ……………………………………………………..………...34 CHAPTER IV-SWIMMING: EDUCATION…………………………….……….....36 Privatized Swim Education ………………………………………………………......39 Public School Education ……………………………………………………………..41 Every Child a Swimmer ………………………………………………………………44 -

Strength and Conditioning for Triathlon: the 4Th Discipline Pdf, Epub, Ebook

STRENGTH AND CONDITIONING FOR TRIATHLON: THE 4TH DISCIPLINE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mark Jarvis | 192 pages | 12 Sep 2013 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781408172117 | English | London, United Kingdom Strength and Conditioning for Triathlon: The 4th Discipline PDF Book From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. With their previous experience, they may assume that they are more ready for triathlon than they really are. By using our website you consent to all cookies in accordance with our Cookie Policy. The triathlon at the Youth Olympic Games also has a 4x mixed relay since , and the event will be introduced at the Summer Olympics. In , it adopted a 4x4 mixed relay format, where each team has two men and two women. Over time changes in hormones such as oestrogen, testosterone and Insulin growth factor 1 IGF-1 can affect the musculoskeletal system including bone health increasing the risks of stress fractures and injury; changes in appetite hormones, gut permeability and gastrointestinal distress, effects on the cardiovascular system and immune function are just a few of the examples of the consequences of low energy availability. The International Triathlon Union ITU was founded in as the international governing body of the sport, with the chief goal, at that time, of putting triathlon on the Olympic program. Whether you work with a trusted friend or a coach, take some time to dig into your abilities before planning out your training. January But the beauty of triathlon lies in working hard to learn new skills and put them all together. International Triathlon Union. Give yourself 7. The lowest-priced brand-new, unused, unopened, undamaged item in its original packaging where packaging is applicable. -

Annual Report 2016 International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 3

International Paralympic Committee Annual Report 2016 International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 2 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 3 Annual Report 2016 Contents President’s welcome 4 The Paralympic Movement and the IPC 8 Consolidate the Paralympic Games as a premier sporting event 12 Empower Para athletes and support the development of Para sports 26 Improve the recognition and value of the Paralympic brand 40 Build sustainable funding 48 Shape organisational capability 54 Foster key strategic partnerships 60 World Para Sports 68 Committees and Councils 88 Images Top 50 moments of 2016 92 (c) Photo Credits: Getty Images (1, 4, 5, 7, 14, 15, 16, 17, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 29, 31, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 40, 41, 42, 43, 45, 47, 48, 49, 54, 58, 60, 61, 63, 67, 86, 87, 88, 89, 92, 93, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99), Scuola Alpina Predazzo (1, 82, 83), Dan Behr (2, 3), IPC (4, 19, 30, 43), Perdo Vasconcelos (8, 9), Rio 2016 (12, 13), OIS (16, 22, 68, 80, 81, 94, 96), Wagner Meier (17), POCOG (20, 71), IBSF (23), Agitos Foundation (31), Görand Strand (32), Joern Wolter (32, 59), Ales Fevzer (36, 27, 70), European Excellence Awards (46), IPC Academy (59), UN / Eskinder Debebe (62), Agenzia Fotografica (72, 73), Roman Benicky (74, 75, 98), Shuhei Koganezawa (77), Heidi Lehikoinen (78,79), Pedro Vasconcelos (84, 85), Channel 4 (95), Augusto Bizzi (95), Bill Wippert (96), Gene Sweeney Jr. (98) International Paralympic Committee International Paralympic Committee 4 Annual Report 2016 Annual Report 2016 5 President’s welcome Key -

DICK's Sporting Goods Announces Roster of More Than 180 Team USA Contenders

NEWS RELEASE DICK'S Sporting Goods Announces Roster Of More Than 180 Team USA Contenders 1/5/2016 PITTSBURGH, Jan. 5, 2016 /PRNewswire/ -- DICK'S Sporting Goods (NYSE: DKS), the ocial sporting goods retail sponsor of Team USA, announced today its roster of more than 180 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Contenders being supported by the Company through exible employment opportunities and sponsorship agreements. To date, over 170 Contenders are currently working in 87 DICK'S Sporting Goods stores in 31 states across the country. The Contenders are oered exible work schedules and competitive compensation, allowing them to devote the necessary time to training to be part of Team USA at future Olympic or Paralympic Games. Athletes from 36 dierent sports, across both Olympic and Paralympic, summer and winter events, are participating in the program. "We're honored to provide these inspiring athletes with what they need – a exible source of income – to pursue their Olympic and Paralympic dreams," said Lauren Hobart, Executive Vice President & Chief Marketing Ocer, DICK'S Sporting Goods. "At the same time, the Contenders are able to oer our customers their expertise as elite athletes. We have had such positive feedback on the program, from the Contenders, our customers and their fellow associates. It's truly a win-win." DICK'S announced a multi-faceted partnership last February, which included the in-store employment program, sporting goods and equipment donations to the U.S. Olympic Training Centers and sponsorships to Team USA 1 hopefuls to help them pursue their Olympic and Paralympic dreams. "DICK'S Sporting Goods' commitment to America's elite athletes through their sponsorship of the USOC and the Contenders program is opening up important new pathways for athletes working to achieve their Olympic and Paralympic dreams," said Lisa Baird, USOC Chief Marketing Ocer. -

Modern Olympics

Modern Oympics Information Gap Developed by colleagues of Nabil Ramzy in Fife, we are rushing this information gap on line in time for the games. Please look at the other information gaps online (e.g. Darwins Birthday or Indus Valley) to decide how you will use it since there are a number of ways pupils can ex- change information. Webaddress http://www.collaborativelearning.org/modernolympics.pdf Last updated 11th June 2012 COLLABORATIVE LEARNING PROJECT Project Director: Stuart Scott We support a network of teaching professionals to develop and disseminate accessible talk-for-learning activities in all subject areas and for all ages. 17, Barford Street, Islington, London N1 0QB UK Phone: 0044 (0)20 7226 8885 Website: http://www.collaborativelearning.org BRIEF SUMMARY OF BASIC PRINCIPLES BEHIND OUR TEACHING ACTIVITIES: The project is a teacher network, and a non-profit making educational trust. Our main aim is to develop and disseminate classroom tested examples of effective group strategies that promote talk across all phases and subjects. We hope they will inspire you to develop and use similar strategies in other topics and curriculum areas. We want to encourage you to change them and adapt them to your classroom and students. We run teacher workshops, swapshops and conferences throughout the European Union. The project posts online many activities in all subject areas. An online newsletter is also updated regularly. *These activities are influenced by current thinking about the role of language in learning. They are designed to help children learn through talk and active learning in small groups. They work best in non selective classes where children in need of language or learning support are integrated. -

VISTA2013 Scientific Conference Booklet Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Bonn, 1-4 May 2013

International Paralympic Committee VISTA2013 Scientific Conference Booklet Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Bonn, 1-4 May 2013 “Equipment & Technology in Paralympic Sports” “Equipment & Technology in Paralympic Sports” VISTA2013 Scientific Conference Gustav-Stresemann-Institut Bonn, 1-4 May 2013 The VISTA2013 Conference is organised by: International Paralympic Committee Adenauerallee 212-214 53113 Bonn, Germany Tel. +49 228 2097-200 Fax +49 228 2097-209 [email protected] www.paralympic.org © 2013 International Paralympic Committee I 2 I VISTA2013 Scientific Conference Table of Contents Forewords 4 VISTA2013 Scientific Committee 6 General Information 7 Venue 8 Programme at a Glance 10 Scientific Programme – Detail 12 Keynote Speakers 21 Symposia - Abstracts 26 Free Communications - Abstracts 32 Free Communications - Posters 78 Scientific Information 102 Scientific Award Winner 103 I 3 I VISTA2013 Scientific Conference Forewords Sir Philip Craven, MBE President, International Paralympic Committee Dear participants, On behalf of the International Paralympic Committee (IPC), I would like to welcome you to the 2013 VISTA Conference, the IPC’s scientific conference that will this year centre around the equipment and technology used in Paralympic sport. This conference brings together some of the world’s leading sport scientists, administrators, coaches and athletes. We hope you can take what you learn over the next few days back home with you to your respective communities to help further advance the Paralympic Movement. The next few days will include keynote addresses, symposia, oral presentations and poster sessions put together by the IPC Sports Science Committee that will motivate and influence you in your respective work environments, no matter which part of the Paralympic Movement you represent. -

Swimming with Limb Absence

Review Article Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering Volume 4: 1–10 Swimming with limb absence: ! The Author(s) 2017 Reprints and permissions: A systematic review sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav DOI: 10.1177/2055668317725451 journals.sagepub.com/home/jrt Bryce TJ Dyer1 and Sarah A Deans2 Abstract Swimming with limb absence is undertaken as a source of leisure or rehabilitation and forms part of the current Paralympic Games competition programme. Whilst it is often proposed that research into sport with limb absence can be limited, this study identified the volume, type and historical interest of research regarding swimming with limb absence. A modified PRISMA search protocol was adopted for this review, and five bibliographic databases were used to identify relevant articles. The review identified 24 papers which met the pre-defined inclusion criteria. The identified peer-reviewed publications dated from 1983 to 2015. The trend of publication indicated an initial focus on the design of prosthetics technology with emphasis then shifting specifically to an interest in swimming biomechanics from 2006. The overall trend of publication in this field is a positive one. In this review, four clear themes emerged. These included the general background of swimming with limb absence, the development of lower limb prosthetics technology, swimming with limb absence whilst performing the front crawl stroke and the technique used by those with unilateral elbow disarticulation. From these, four further themes have been identified for pursuit in the immediate future. This review will assist those who are interested in prescribing swimming with limb absence as a form of exercise or to those who wish to pursue it competitively. -

The Paralympic Athlete Dedicated to the Memory of Trevor Williams Who Inspired the Editors in 1997 to Write This Book

This page intentionally left blank Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science The Paralympic Athlete Dedicated to the memory of Trevor Williams who inspired the editors in 1997 to write this book. Handbook of Sports Medicine and Science The Paralympic Athlete AN IOC MEDICAL COMMISSION PUBLICATION EDITED BY Yves C. Vanlandewijck PhD, PT Full professor at the Katholieke Universiteit Leuven Faculty of Kinesiology and Rehabilitation Sciences Department of Rehabilitation Sciences Leuven, Belgium Walter R. Thompson PhD Regents Professor Kinesiology and Health (College of Education) Nutrition (College of Health and Human Sciences) Georgia State University Atlanta, GA USA This edition fi rst published 2011 © 2011 International Olympic Committee Blackwell Publishing was acquired by John Wiley & Sons in February 2007. Blackwell’s publishing program has been merged with Wiley’s global Scientifi c, Technical and Medical business to form Wiley-Blackwell. Registered offi ce: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK Editorial offi ces: 9600 Garsington Road, Oxford, OX4 2DQ, UK The Atrium, Southern Gate, Chichester, West Sussex, PO19 8SQ, UK 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030-5774, USA For details of our global editorial offi ces, for customer services and for information about how to apply for permission to reuse the copyright material in this book please see our website at www.wiley.com/wiley-blackwell The right of the author to be identifi ed as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, except as permitted by the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, without the prior permission of the publisher. -

2012 U.S. Olympians, Paralympians, Hopefuls Launch New Class of Team for Tomorrow in Advance of London 2012 Games Include Anjali Forber-Pratt

2012 U.S. Olympians, Paralympians, hopefuls launch new class of Team for Tomorrow in advance of London 2012 Games include Anjali Forber-Pratt Colorado Springs, Colo. – Team for Tomorrow, a program launched in 2008 by America’s Olympic and Paralympic athletes and the United States Olympic Committee, continues to make a difference for those in need around the world. Today, the USOC announced details of the 2012 program, including the roster of 2012 Team for Tomorrow Athlete Ambassadors and a partnership with the YMCA and Boys & Girls Clubs of America – both Multi-Sport Organizations within the U.S. Olympic Family. Team for Tomorrow is a humanitarian relief effort through which U.S. athletes offer assistance and support to people around the world who are in need. Humanitarian relief and assistance takes place in the form of donations, volunteerism, disaster recovery support, advocacy and other contributions to communities. The program offers U.S. athletes a way to stay connected to sport in a meaningful way, finding new significance in what it means to represent their country. The Team for Tomorrow Athlete Ambassadors will serve as captains of the program on behalf of the entire 2012 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Teams. As ambassadors, this select group of athletes will act as advocates and champions of the effort, educating their U.S. teammates and spreading awareness about Team for Tomorrow’s causes for the 2012 U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Team. The ambassadors include: Tony Azevedo, water polo Rachel Dawson, field hockey Anjali Forber-Pratt, Paralympic track & field Rudy Garcia-Tolson, Paralympic swimming Jessica Hardy, swimming Gwen Jorgensen, triathlon Tim Morehouse, fencing David Oliver, track & field Heather O’Reilly, soccer Mary Whipple, rowing “I decided to get involved with Team for Tomorrow because it provides an opportunity to give back,” said Oliver, 2008 Olympic bronze medalist in the 110-meter hurdles and London 2012 hopeful.